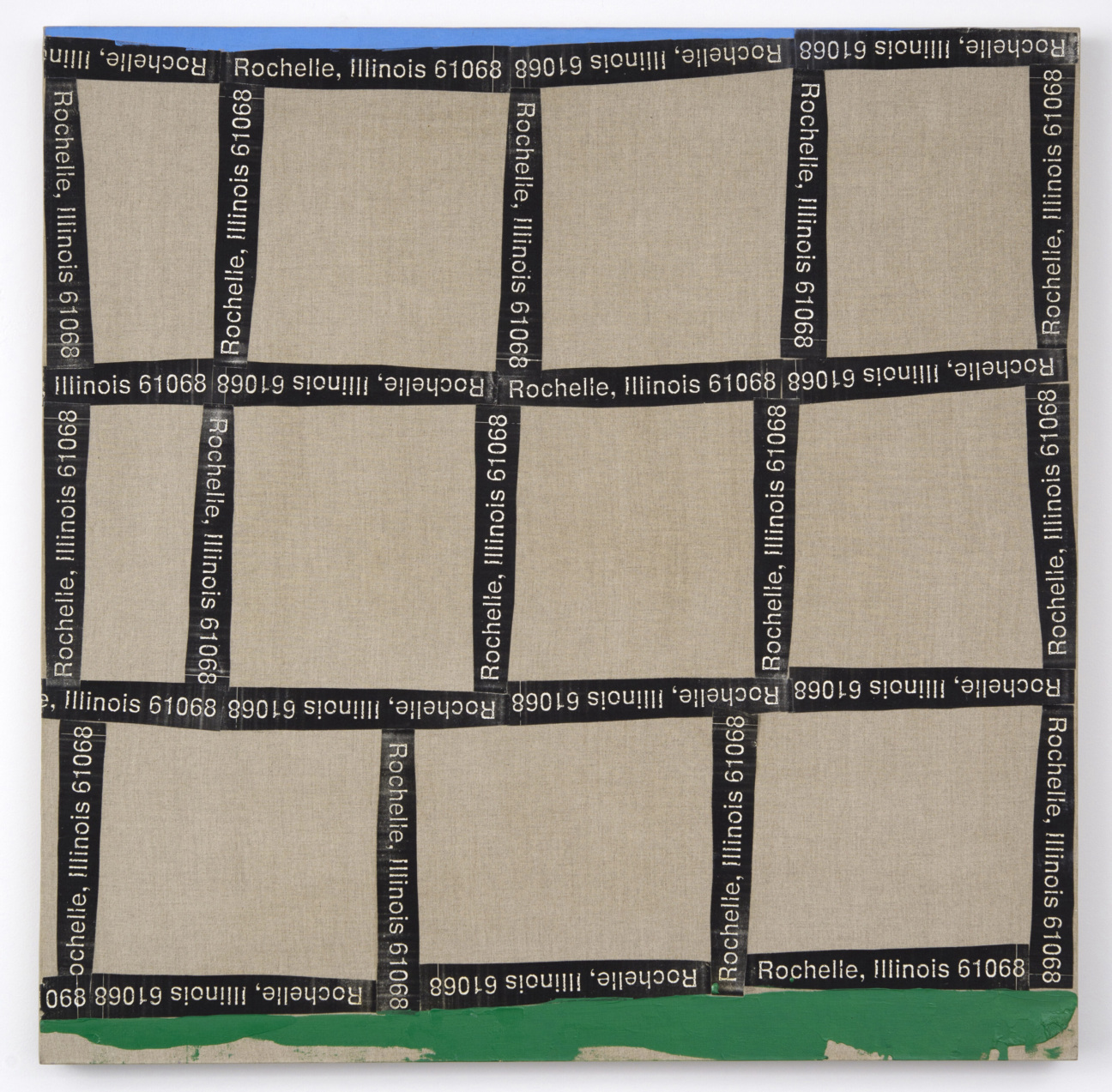

"You Again" by Rochelle Feinstein

Bridget Donahue New York, Candice Madey New York, Nina Johnson Miami, Hannah Hoffman Los Angeles, Francesca Pia Zurich, and Campoli Presti Paris

Last January, Candice Madey Gallery opened a sprawling, six-venue exhibition of new and known works by Rochelle Feinstein. The collaborative show, titled “You Again,” was facilitated by six women-led galleries who share representation of the artist, an experimental choice that stands out as remarkably collaborative in an otherwise highly competitive market environment. Arranged thematically by venue, the exhibition spotlit Feinstein’s continued exploration of the floral form, drawing on painting “tropes”—most often abstraction—to craft subtle commentaries on pop culture, mass production, and humanity’s growing alienation from the natural world. Newer contributions to Feinstein’s floral study included a series of works on cardboard, a reference to Amazon’s exploitative business model, and our culture’s hunger for instant gratification. The show marked the first of many ambitious Feinstein exhibitions by the six-gallery consortium.

"Chronicling Our Lives: 1987-2021" by Willie Birch

Fort Gansevoort New York

Willie Birch has always been a bit of a renegade. Over the course of his 50-plus-year career, the artist has remained committed to Realism, eschewing the commercial art world’s trend towards abstraction and conceptualism. And though figuration itself generally favors painting on canvas, he works exclusively with paper. His solo New York exhibition at Fort Gansevoort earlier this year was a gesture in storytelling that covered more than three decades of his oeuvre with pieces that are animated by the presence of Birch’s own world and the immediacy of his own experiences. As he told CULTURED ahead of its opening: “The best art is motivated by what’s around you.”

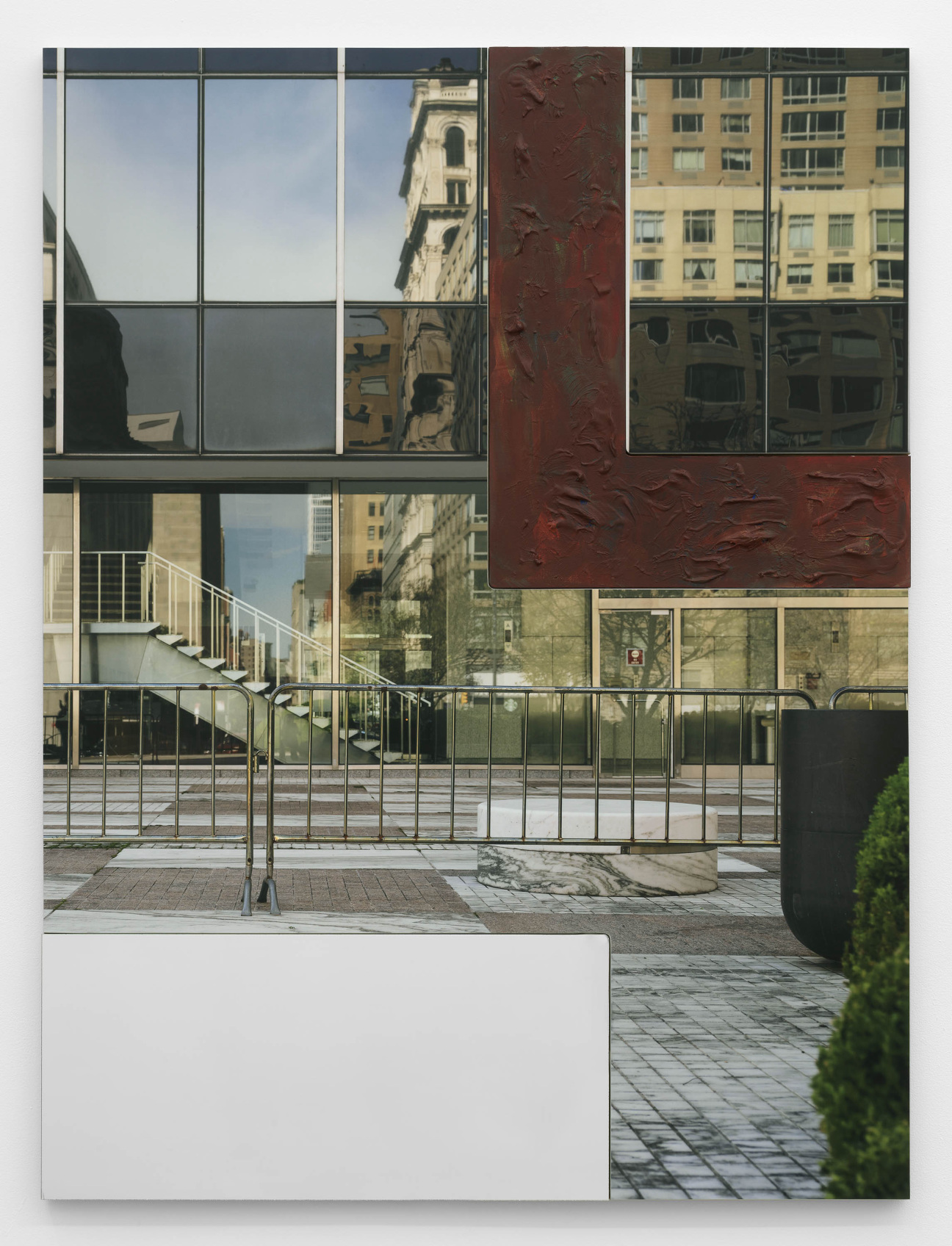

"Civic Center" by John Miller

Maxwell Graham/Essex Street New York

The Civic Center—the anvil-shaped pocket of Lower Manhattan that spans the Financial District to Chinatown—was the subject of John Miller's spring exhibition of the same name. Staged at Maxwell Graham's Two Bridges gallery—not too far from its controversial subject—the show included nine works from the critic and artist, who is best known for the relief sculptures and assemblages he began making in the mid-'80s. From wall pieces to carpet works and a large-scale wallpaper installation, "Civic Center”' challenged the efficacy of civil service at the intersection of bureaucracy and recent protest.

"Marcel Duchamp"

Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt

As Marcel Duchamp once said, “anything is art if an artist says it is.” The radical French artist was as infamous for founding the principles of the Conceptual Art movement as he was for tearing them apart. Through experimentation, dimensionality, and humor, Duchamp—who also went by the pseudonym Rrose Sélavy, a double entendre and female alter ego—famously had Post-Impressionist and Cubist beginnings before he rejected "retinal art" for a practice that was “in the service of the mind." Browsing his eponymous retrospective at MMK his past fall, the first comprehensive exhibition in two decades to span the 60 years of Duchamp’s work, one can follow his spiral into art-science experiments, Dadaism, and "Readymades"—what the artist termed ordinary objects that he projected meaning onto—first hand. Works with literal titles such as Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913/1964 or Porte-bouteilles (Bottle Rack), 1914/1964, and his controversial Fountain, 1917/1964, further begot his point: “An ordinary object [could be] elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.”

"The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Raphael"

The National Gallery London

Few artists have shaped the course of Western culture quite like Raphael. The Italian High Renaissance painter died in the year 1520 at the age of 37 after a brief but history-defining 20-year career that spanned painting, poetry, architecture, and textile design. In fact, it took almost half as long (six years) to bring this sweeping exhibition at London’s National Gallery to fruition. Originally slated to coincide with the 500th anniversary of the painter’s death in 2020, the pandemic pushed the opening back to last April, a curse that ended up a blessing: the curatorial team had time to dig deeper into Raphael’s complete works, producing the most in-depth exhibition on the artist to date, and illuminating the throughlines that connect his painting, writing, and architectural practices.

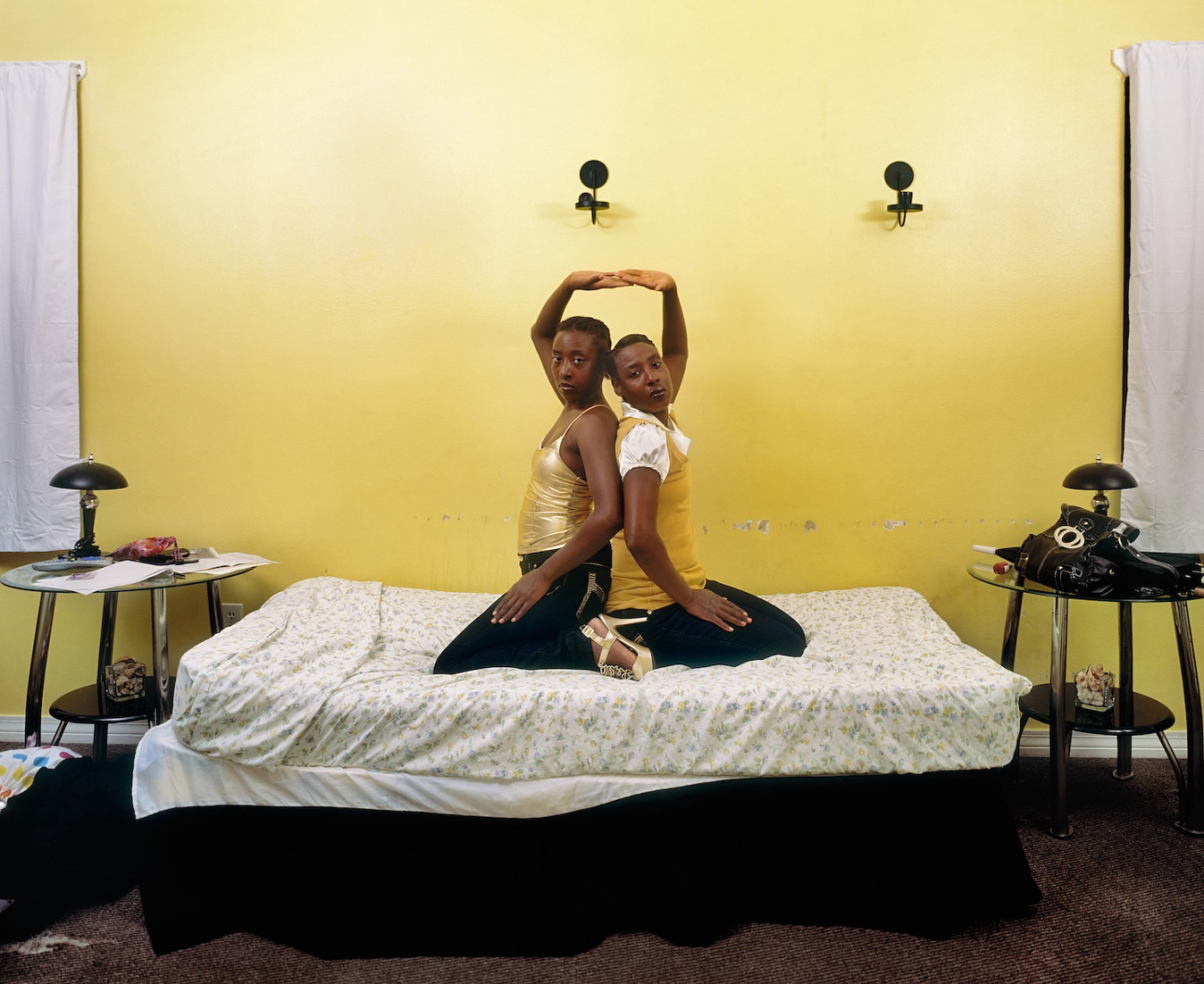

"Deana Lawson" by Deana Lawson

MoMA PS1 New York, Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, and High Museum of Art Atlanta

“I know that I want people to get a certain feeling,” Deana Lawson told CULTURED last year, describing her practice. “I want it to creep up on you and stay with you; the power of the still photograph.” The visual artist has been documenting the beautiful complexities of Black representation for the past 15 years through large-scale, elaborately staged photographs, and her first museum survey did not hold back. Presenting over 50 works in a chronological narrative—from her better known “Family” works to society-focused works such as Hair Advertisement, 2005—the eponymous exhibition was co-organized with the Institute of Contemporary Art and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, where it is on view until February 2023.

"Live Evil" by Arthur Jafa

LUMA Arles France

For more than three decades, Arthur Jafa has snaked his way through film, photography, and sculpture with an unyielding dedication to shaping and transforming a Black aesthetic. As a cinematographer, the artist’s blistering and tender work—focused on questioning the ontologies of race, power, repression, and survival, and the persistent beauty in their midst—can be seen in Spike Lee’s Crooklyn, 1994, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, 1991 (which won Sundance’s Best Cinematography award), and in Solange’s “Cranes in the Sky” and “Don’t Touch My Hair” music videos. But it is his work with found footage that established him as an art world visionary. In April of 2022, two of the vast halls at LUMA Arles in southern France were given over to the most expansive presentation of Jafa’s work to date. Composed of recent and new video, photographic, and immersive sound works, “Live Evil” memorialized Black culture while interrogating the forms of media and image-making that can threaten it. Four looming billboards filled the industrial space of LUMA’s La Grand Halle, plastered with homages to music icons like Miles Davis and Albert Ayler, while mesmerizing film installations like AGHDRA and LOML, 2022, experimented with landscape, light, and shadow to explore subjects of grief and environmental destruction. In La Mécanique Générale elsewhere on the art center’s campus, walls collaged with archival images evoked the plurality of Black experiences in the U.S., and paved the way for a range of futures: “I’m trying to demonstrate the value of things that are not considered valued,” Jafa told CULTURED in 2019. “I’m also trying to demonstrate the possibility of creating the new. Emerging something else, provoking something else, creating new actualities.”

To See The Earth Before the End of the World by Precious Okoyomon

Venice Biennale

CULTURED 2020 Young Artist Precious Okoyomoni s known for their ambitious installations that employ organic material to explore the material entanglements between global ecological transformation and the historical construction of race. But in the poet’s deeply ambivalent work, pain, beauty, humor, and growth coexist—troubling audiences who have come to expect easy answers and tidy moral conclusions. For this year’s Venice Biennale, the rising Nigerian-American star constructed an elaborate environment, overgrown with sugarcane and the highly invasive Japanese vine kudzu— both plants bound up with the transatlantic slave trade—and teeming with butterflies. The experiential artwork guided visitors through a procession of figurative sculptures made out of raw wool, dirt, and blood. Inspired by Édouard Glissant’s 1961 play Monsieur Toussaint, the installation— simultaneously living and decaying—looked to revolution, both biologically and historically, as a model for a new way of being.

"The Red Studio"

Museum of Modern Art New York and National Gallery of Denmark Copenhagen

In 2022, it’s nearly impossible to escape Henri Matisse's nude etchings, which have found a second wind of virality thanks to social media-influenced interior design. MoMA’s blockbuster summer exhibition, however, focused on another iconic work from the Fauvist. Reuniting The Red Studio—a landmark for modern studio painting since its 1911 creation—with the surviving six paintings, three sculptures, and one ceramic seen in the painting itself, the eponymous exhibition explored the radical nature of its creation. "Where I got the color red—to be sure, I just don't know," the artist once remarked. "I find that all these things…only become what they are to me when I see them together with the color red."

"Black Chapel" by Theaster Gates

Serpentine Pavillion

It’s been a big year for Theaster Gates, who in addition to staging three New York occurrences this fall, spoke to CULTURED cover star Chance the Rapper for the magazine’s Winter 2022 issue. But before all of that, the Chicago-based artist, professor, and curator presented a cylindrical Black Chapel for the Serpentine Gallery’s annual summer pavilion at London’s Kensington Gardens this year. Designed with the help of Adjaye Associates, the standalone structure contained a large bronze bell at its entrance salvaged from the demolished Chicago St. Laurence church, as well as “Seven Songs for Black Chapel,” a series of tar paintings by the artist.

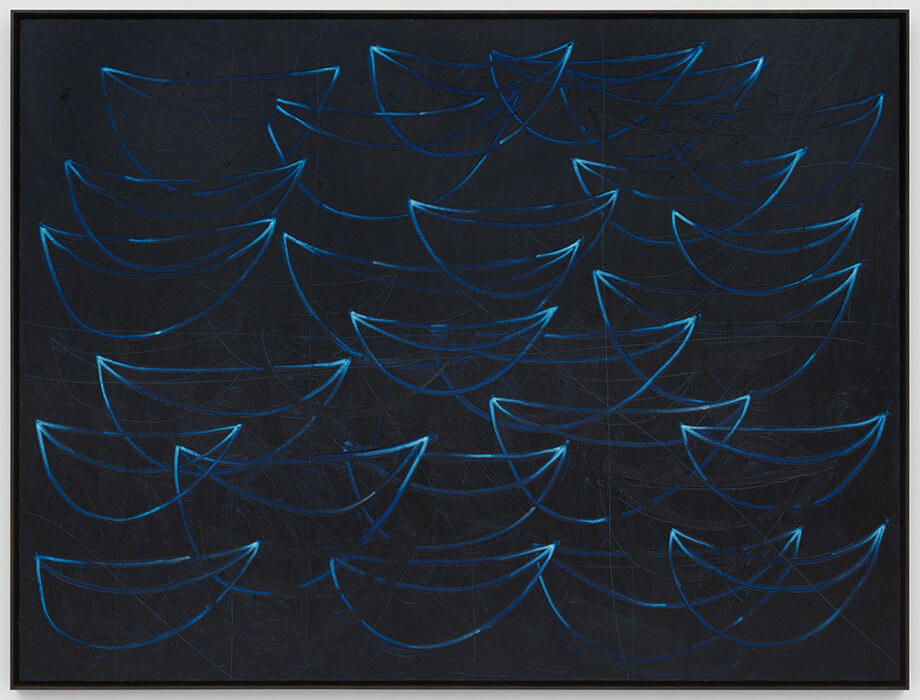

"Sodade" by Rashid Johnson

Hauser & Wirth Menorca

Rashid Johnson staged his first solo exhibition, “Sodade,” in Spain at Hauser & Wirth—a 16,000 square-foot space on Illa del Rei, a 10-acre island nestled in an inlet of the already tiny island of Menorca. The location, accessible only by boat and across from the ruins of a Basilica and an 18th-century naval hospital, offers an otherworldly backdrop for the artist’s latest work. The exhibition featured nine “Seascape” paintings, rendered in rich blues and textured neutral whites, created in Johnson’s signature wiping away method, but rendered for the first time in oil paint. “Sodade” also featured new iterations of Johnson’s “Anxious Man” series, and three “Bruise” paintings meticulously layered with blacks and blues. These latter inclusions created a sense of unease in the space that contrasted the "Seascapes," a deliberate juxtaposition that marked a continuation of the artist’s focus on migration, diaspora, and displacement. The exhibition took its name from a Cape Verdean song about yearning and melancholia, challenging viewers lucky enough to make their way to the remote locale to ponder the tumultuous history of the island, which weathered centuries of wars, religious crusades, and enslavement on its shores.

"MASK / CONCEAL / CARRY" by Tiona Nekkia McClodden

52 Walker New York

The founder and director of Conceptual Fade, Tiona Nekkia McClodden explores shared values and traditions within the African diaspora—the “Black mentifact,” as she described it to CULTURED earlier this year. One of her two concurrent New York shows this summer, “MASK / CONCEAL / CARRY” was layered with meaning that slowly revealed a “variable Blackness” as the viewer moved through 52 Walker’s sweeping TriBeCa gallery. Largely consisting of firearms and fragments in low relief, molded, and on pedestals, the show also featured painted and printed works that spelt out words such as “My Trace / My Ruin” as well as moving imagery. Installed under custom lighting, the Philadelphia-based artist abstracted visibility to create a space to engage with complex, difficult issues, while also giving the viewer room for personal introspection.

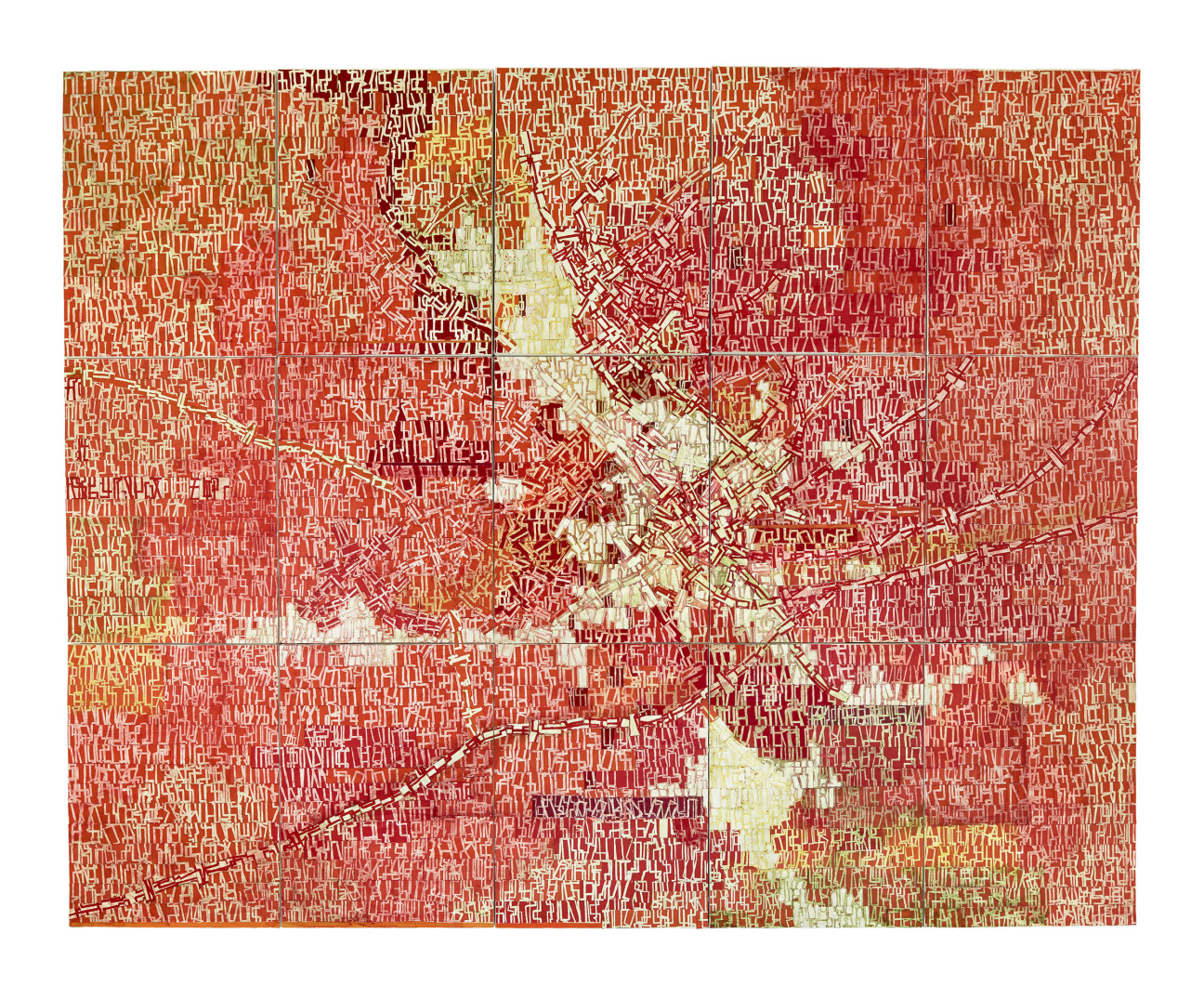

"Meditations on Social Sculpture" by Rick Lowe

Gagosian New York

This fall, Rick Lowe staged his first New York solo exhibition, “Meditations on Social Sculpture,” at Gagosian. The show, which was also the artist’s first since joining the gallery’s roster in 2021, spans the artist’s multi-decade oeuvre—from his “social sculptures,” or works rooted in community participation, to the abstract paintings that evolved from those place-based social engagement projects. Project Row Houses, 1993-2018, saw the artist transform a number of crumbling shotgun houses in Houston’s Third Ward (one of the city’s oldest and most historically rich Black neighborhoods) into residences and workspaces for low income people. Conceived in collaboration with fellow artists and community organizers, the project offered grants and fellowships to artists, funneling the fruits of their labors back into the neighborhood through exhibitions and programming. The Greenwood Art Project in Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2018–2021, focused on raising awareness around community traumas, historic erasure, and migration following the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. From these multimodal civic engagement projects, Lowe crafts arresting paintings characterized by granular, grid-like mark making that alludes to cartographical practices like redlining that facilitate forms of systemic deprivation. The paintings are just the tip of the artist’s iceberg—mosaics that allude to a larger practice of cultural transformation and critique.

"Youth" by Anne Imhof

Stedelijk Amsterdam

This October, “Youth,” Anne Imhof’s first solo exhibition in the Netherlands, opened at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. An exciting voice in the art world, Imhof’s name is poised to break into the mainstream—she brought home the Gold Lion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, and cracked the top 10 of Art Review’s “Power 100 List” last year. Despite growing acclaim, Imhof remains elusive, chaotic, and unpredictable. What else would you expect from an artist whose first performance on the world stage was a staged boxing match (Faust, 2017), and who followed that tough act with 2019’s Sex at the Tate Modern—a performance with a heavy metal-laced score during which Imhof texted directions to her team in the gallery as they reacted to the raw energy in the room. “Youth,” an immersive installation that the Stedelijk describes as simultaneously “disorienting, oppressive, and intimate,” transforms a cavernous gallery space into a menacing labyrinth of cold metal surfaces and low light. The experience, on view until the next month, is accompanied by new video works which the artist filmed in a snow-covered Moscow suburb.

"Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces" by Linda Goode Bryant

Museum of Modern Art New York

Nearly 50 years after Linda Goode Bryant established Just Above Midtown, a haven for Black artists in an otherwise white-dominated art scene, in 1974, the gallerist continues to foray into the unknown. At the time of its founding, JAM was a space of resistance against the commodification and homogenization of Black artists and their work, and a Petri dish for experimentation and risk that altered the fabric of the New York contemporary art world. While JAM closed its doors in 1986, Goode Bryant has persevered: the longtime gallerist is also a filmmaker (she collaborated with the documentary director Laura Poitras on Flag Wars, a film about the gentrification of her hometown, in 2003), a farmer (she launched the urban farming organization Project EATS in 2009), and an entrepreneur. Goode Bryant’s legacy—which, she told CULTURED earlier this year, is characterized by “vision, belief, resourcefulness, and determination,” is now memorialized at MoMA. The exhibition, titled “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces,” explores the radical art space’s history through archival imagery, gallery ephemera, and works by artists like Senga Nengudi, Mallica Reynolds, and Suzanne Jackson, who others passed through JAM’s doors during its heyday.

"Joan Didion: What She Means" by Hilton Als

Hammer Museum Los Angeles and Perez Art Museum Miami

How does one portray a being whose words immeasurably colored our world? For “Joan Didion: What She Means,” noted writer and curator Hilton Als looked to nearly 50 contemporary artists —from Félix González-Torres to Betye Saar—to translate Joan Didion's written consciousness into an emotional and visual language. "Joan was porous, meaning she was open to your experiences as much as she was to her own," he told CULTURED ahead of the show’s opening a few months back, recalling his decades-long friendship with the late writer. The four-part exhibition runs until February and mixes visual artworks—some inspired by Didion, others with a parallel affinity—with historical and cultural objects to narrate the life of one writer by another.

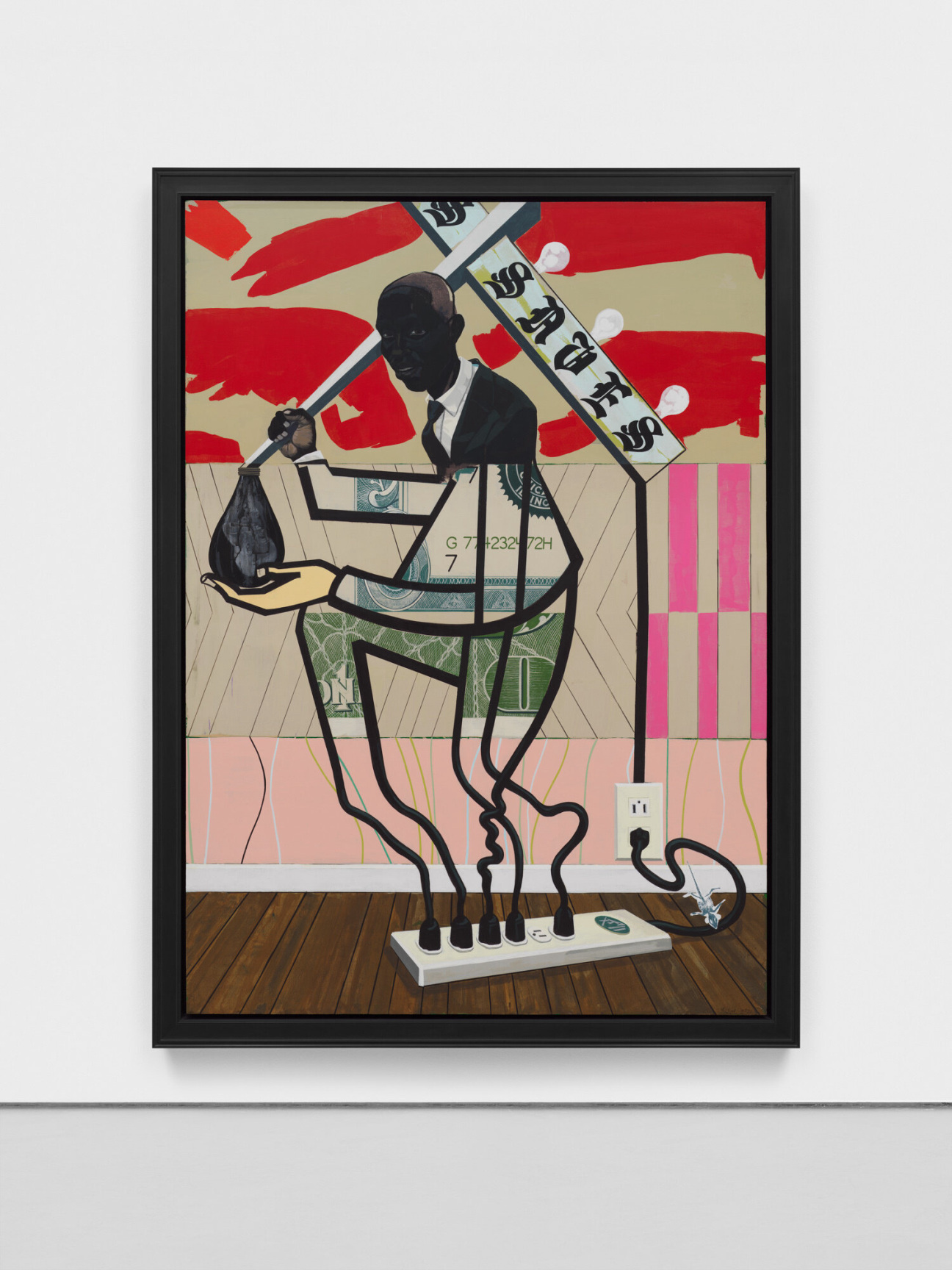

"Exquisite Corpse: This Is Not The Game" by Kerry James Marshall

Jack Shainman Gallery New York

Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall has spent his life patiently honing his skills and fashioning a space for himself in grand painting traditions. From 18th Century French Rococo to the saintly style of Italian Renaissance masters, the artist has seized upon the canon of historical portraiture to depict the Black experience—much of which was shown in his 2016 Met survey. In "Exquisite Corpse: This Is Not The Game" at Jack Shainman, Marshall turned his attention to Surrealism, pulling inspiration from the titular 1920s game that the Surrealists once used to collectively create new, randomized works. But rather than a Frankenstein of varied contributors, Marshall’s mashups—exquisitely humorous and beautifully absurd—were all his own.

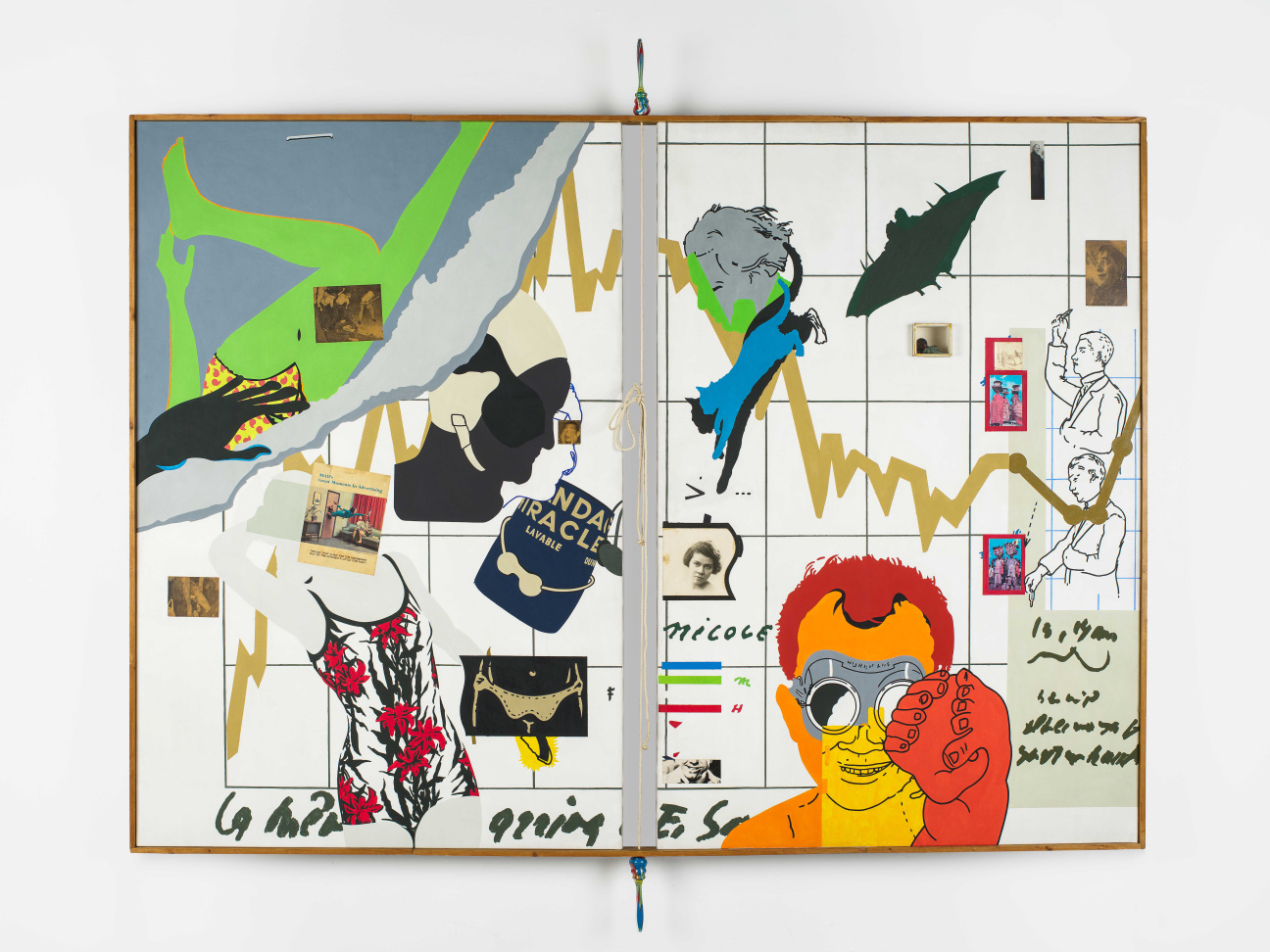

"A Hopscotch of the Mind" by Hervé Télémaque

Sepentine Gallery London and Aspen Art Museum

Throughout his roughly 60-year career, Hervé Télémaque moved through artistic movements with unaffected ease. The Haiti-born painter made his way to Paris in the 1960s, after feeling disaffected by a brief stint in the U.S. that forced him to navigate racial segregation and an art scene dominated by Abstract Expressionism. In the French capital, the young painter fell in with the Surrealists, and later his bright compositions featuring cartoonish figures, brand logos, and contemporary signage that offered incisive critiques of mass culture and neocolonialism became a founding force in the Narrative Figuration movement. The traveling exhibition, titled “A Hopscotch of the Mind,” is true to its name, featuring a non-chronological assembly of the artist’s paintings and assemblages, made from the late 1950s to the present day. It originated at London’s Serpentine Gallery at the beginning of the year before traveling to the Aspen Art Museum, where it remains on view until the spring of 2023.

"The Rhythm of Vision" by George Clinton

Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles

Works by the painter, sculptor, and world-renowned godfather of funk are currently on view at Jeffrey Deitch in Santa Monica. “The Rhythm of Vision” marks George Clinton’s first art exhibition in Los Angeles, but it’s far from his first visit to Deitch’s 7000 Santa Monica Boulevard space—the iconic musician recorded several of his hit-making records in the space during the building's past life as a music studio called Radio Recorders. The exhibition features psychedelic assemblages and works in spray paint that translate Clinton’s afrofuturist mythos from the lyrical to the visual realm. “The Rhythm of Vision” kicked off in November with a spoken word performance by the artist, who stood atop an otherworldly stage—a cross between an ethereal parade float and a graffiti-covered spaceship— crafted by Lauren Halsey, a dedicated admirer of Clinton’s.

"Henry Taylor: B Side" by Henry Taylor

Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles

Once known simply as "Chinatown"—after the LA neighborhood he has long inhabited—Henry Taylor is finally receiving his roses. After solo shows at Harlem's Studio Museum and MoMA PS1, and a splash at the Whitney Biennial, this fall MOCA debuted the most comprehensive retrospective of the artist yet. Surveying 30 of Taylor’s multidisciplinary works 22 years after his hometown gallery debut, "B Side," which will be on view until the spring, presents empathetic figuration beside totemic sculptures that, much like his portraiture, reveal the deeper meaning of the seemingly everyday. “Sometimes I could be Van Gogh painting a cornfield,” Taylor told CULTURED in 2017. “Sometimes I just want to paint my momma. I might want to paint flowers, but I haven’t gotten there yet.”

"Progressive Aesthetics" by Michel Majerus

Institute of Contemporary Art Miami

“Progressive Aesthetics” is the first museum retrospective of the late painter and digital media artist who died in a plane crash in 2002. The exhibition, which opened last November and runs through the spring of 2023, features works from the early ‘90s up until the Luxembourger artist’s untimely death. Despite the tragedy that bookends Michel Majerus’s career, his works reflect a jubilant but wry embrace of pop culture and technology, and an irreverent approach to matters of authenticity and originality. Featured in the exhibition are a number of screen printed images from Andy Warhol’s notorious 1985 collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, which Majerus altered and iterated upon to raise questions about the nature of originality and appropriation. Also on view are a number of paintings from the artist’s “Splash Bombs” series, in which the logo of the eponymous pool toy brand is layered upon itself in a feverish consumerist frenzy.

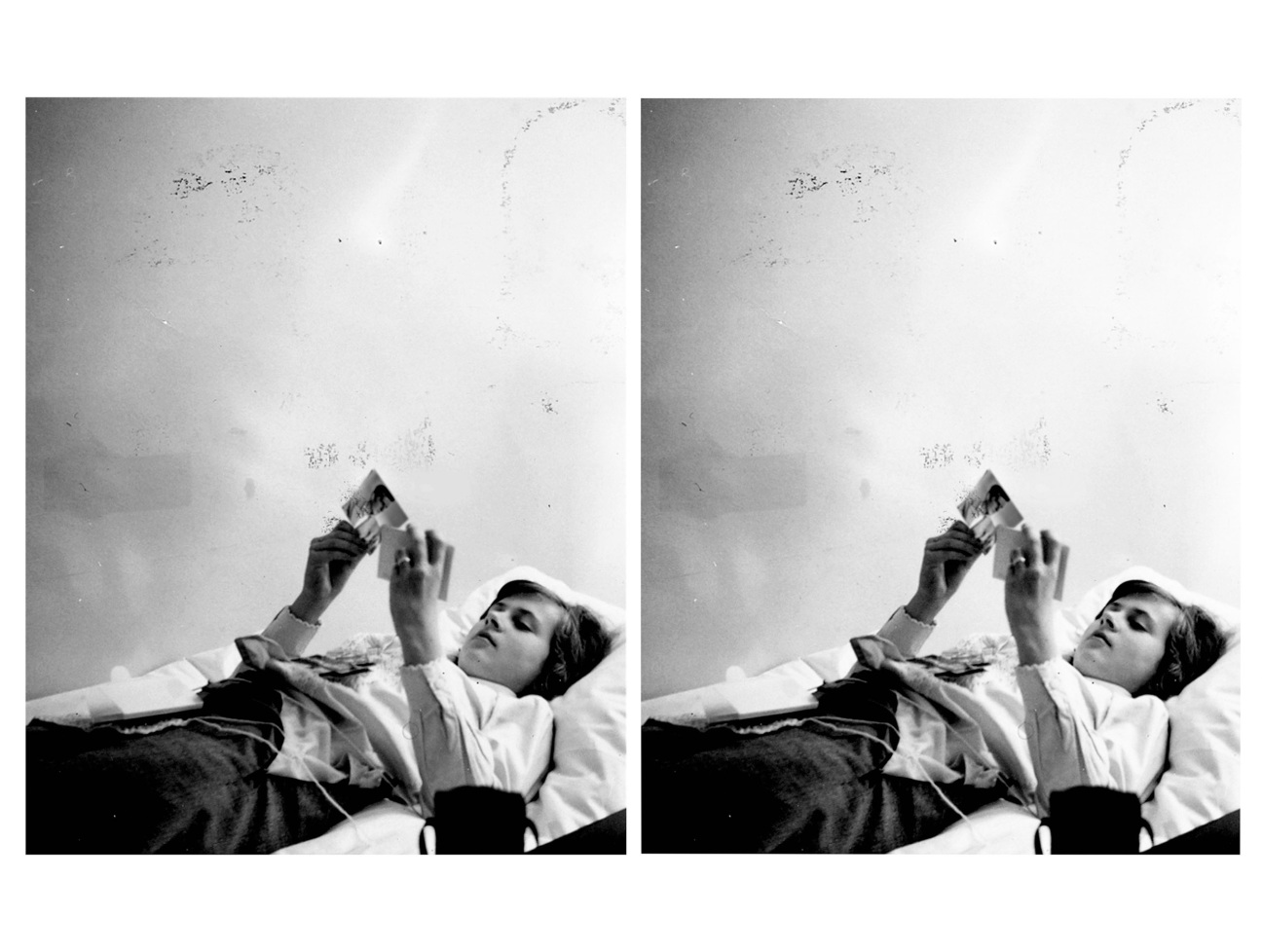

"Rosemarie Trockel" by Rosemarie Trockel

Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt

Rosemarie Trockel’s practice defies any attempt at an elevator pitch. Since the 1980s, the German conceptual artist has been making works that bridge mediums and embrace the absurd—geometric “paintings” made with knitting machines, bronze seals wearing collars of artificial human hair, eerie designs screen printed directly onto gallery walls, elaborate book jackets with no books inside them—all of which wrestle with issues of power, desire, and gender domination. Trockel deploys bluntness and subtlety in tandem, drawing with equal reverence from intellectuals of the Western canon (Hannah Arendt, Karl Kraus, and Marquis de Sade) and from “less respected” realms (hot plates and home appliances nod to the domestic sphere, the ubiquitous Playboy Bunny motif to the crassness of popular culture). This month, Frankfurt’s MMK opens Trockel’s eponymous exhibition, which features works from the 1970s to the present day, including a number of pieces from her Book Drafts series,1982-1997, and Unplugged, 1994, an array of stoves and hotplates that explore female rage and the relegation of women to the home.

in your life?

in your life?