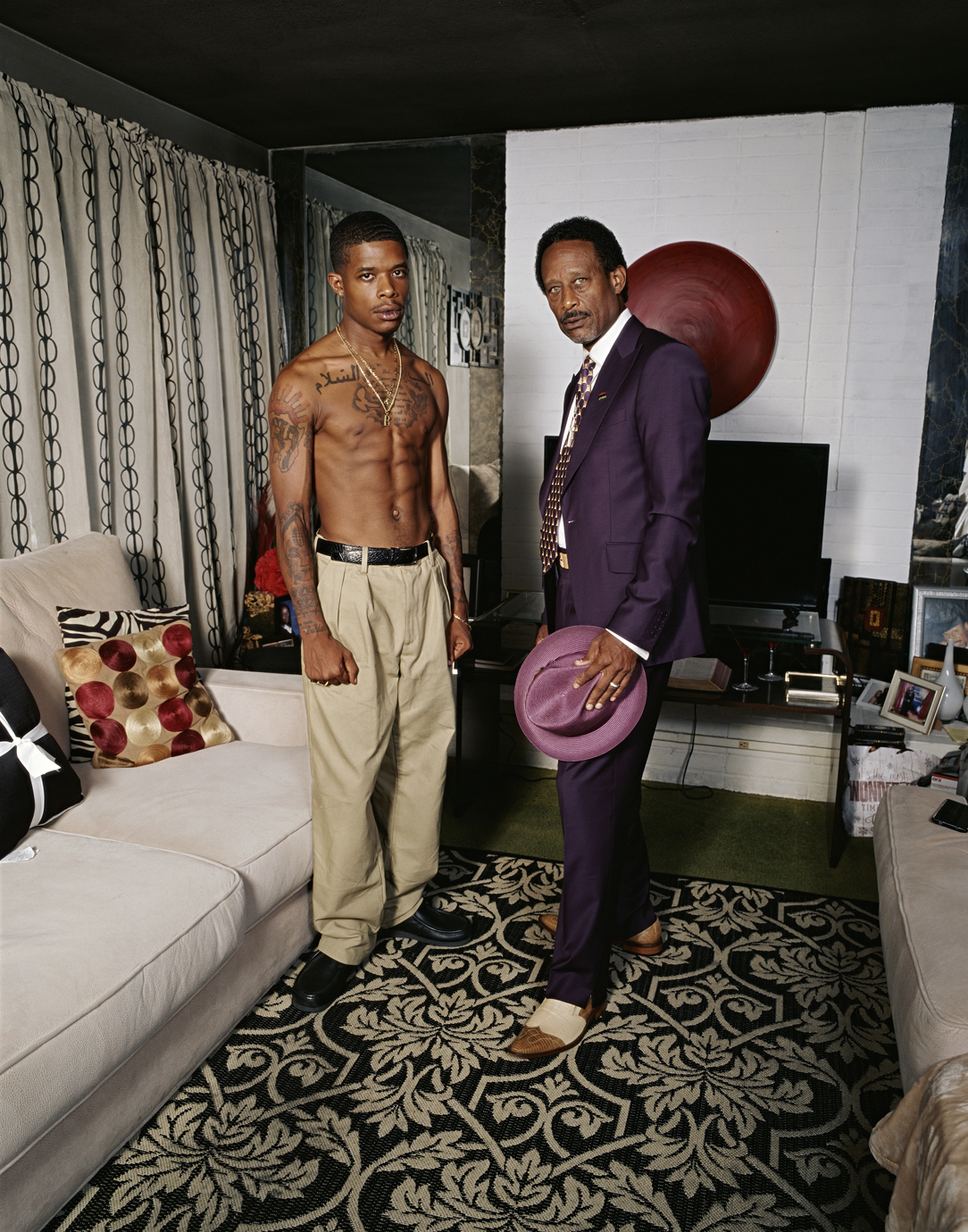

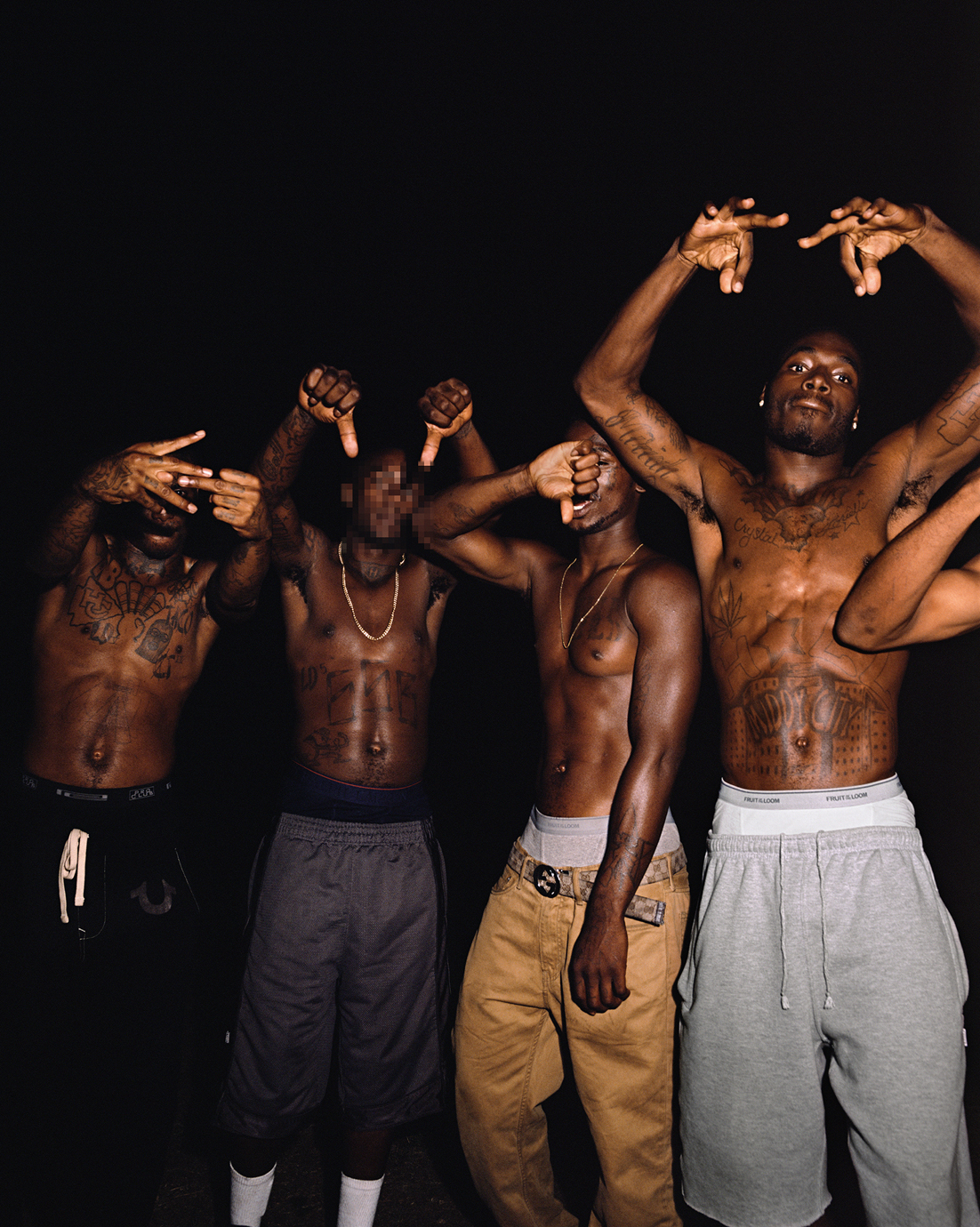

Black people have been positioned and produced as subjects to experience such a disproportionate reality, one where they’ve been displaced and prohibited from owning property (capital) or building empires. Their hands have been forced in that they came to own and define culture, but only were able to innovate in certain ways given the technology available to them at the time, whether that be language, sound or, more recently, the Internet. What else to do when the only architecture available for you to thoroughly inhabit and explore is your body? That’s the driving ethos behind Deana Lawson’s art practice and photography work.

Last week, I spoke to Lawson about her forthcoming show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and her recent implementation of mirrored frames into her work. Lawson refers to these as a “silver reflective lining between the subjects, who are being seen by the audience and figures that see as well,” which further siphons and exaggerates the subject/participant dynamic. When asked about the theme, Lawson is quick to pronounce that it is “a continuation of the larger body of work, but this show takes on the manifestation of the spectral quality that’s always been there subtly. But now it’s being taken to the next level in terms of how history and futurity is presented, and not in the Photoshop or post-production realm of things either. I’m talking about the more traditional photographic sense.”

It’s important to think of photography as a considered craft beyond the mores of representation that have conditioned us to deftly justify pointing the capturing device at Black-skinned individuals and collective bodies of people near and far as a revolutionary practice or politic. Photography is a science, it’s a sacred practice and profession that requires something to be given away in order that something can be captured—it’s less oriented and anchored to capital (monetary exchange), but it’s more about an energy exchange than anything else, where the person in front of the camera has to trust you in order to give pieces of themselves away.

Lawson is the 2020 Hugo Boss Prize winner and the 13th artist and first photographer to win the prize since its inception in 1996. The recipient receives an honorarium of $100,000 and a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York. I was wondering how to think through and describe a canonical Lawson image and the only likenesses that plagued my mind were figures who define the Renaissance movement. You know: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Sandro Botticelli and Caravaggio. Compositionally, it’s the only reference that lives in my head and doesn’t compromise the integrity of Lawson’s sheer grit and ingenuity. Her work is also a visual composite that aligns with the portraits of King Louis XIV and the royal family of Versailles. See, I’m in a bit of a word, image, and reference bind, in which I’m trying to figure out: How do you reference something without saturating it or leaving it overexposed, even vulnerable?

“How does one describe those who haunt a Deana Lawson photograph?” is a question that has perplexed me, and King Louis XIV, also known as the Sun King, is a good surrogate/pioneer. I would go so far as to even call him an architect, because of how he used and activated the materials and technology available to him during his reign in France. He constructed the Palace of Versailles after growing tired of his time in the city, deciding to erect a monumental emblem and symbol to represent what would become France’s center of entertainment, culture and art. I have been enamored with King Louis XIV ever since visiting Versailles a few times and bearing witness to the family portraits that dress and define the halls of the palace.

In answering the question and call of what makes Lawson’s photographs sing, I started thinking about the failure of the conversation around politics of representation. I think an inherent misconception of the discourse on representation politics is the idea that in order to re-present, listening to the image and seeing the subject is a requirement. It brings to mind a quote by scholar Tina Campt from her seminal work Listening to Images (2017), where she writes of the problem of ensuring Black futurity and asks, “How does a Black feminist grapple with a future that hasn’t happened but must, while witnessing the mounting disposability of Black lives that don’t seem to matter? What constitutes futurity in the shadow of the persistent enactment of premature Black death?” To which she later answers, “Through these images they fashion a futurity they project beyond their own demise. Rather than fleeing or submitting to a future imposed upon them, they face down the image that would negate the complicated truth of the lives they have lived, in order to interrupt the narrative of their own demise that threatens to extinguish their capacity to claim a life lived in dignity and complexity.” To which I would say that the driving ethos of Lawson’s photography concerns itself more with the question: How does one lay claim or give photo/imagraphic proof and integrity to the lives and legacies that are often denied? In Lawson’s case, you must stage it to claim.

When asked about her practice and if people have ever understood what her work is about, she says, “I think they feel the energy, and I know that I want people to get a certain feeling. I want it to creep up on you and stay with you; the power of the still photograph has a staying power. To be honest, sometimes interviews are hard and writing artist statements is hard because I’m always trying to figure out how I’m going to give them that feel, that’s why I tend to shy away from giving interviews. I’m able to get at the root of what writing can do; there’s something about prolonged thought that I tend to do much better in. Being a witness makes me think of more photojournalistic photography, whereas mine is, well, I don’t know how to describe it.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?