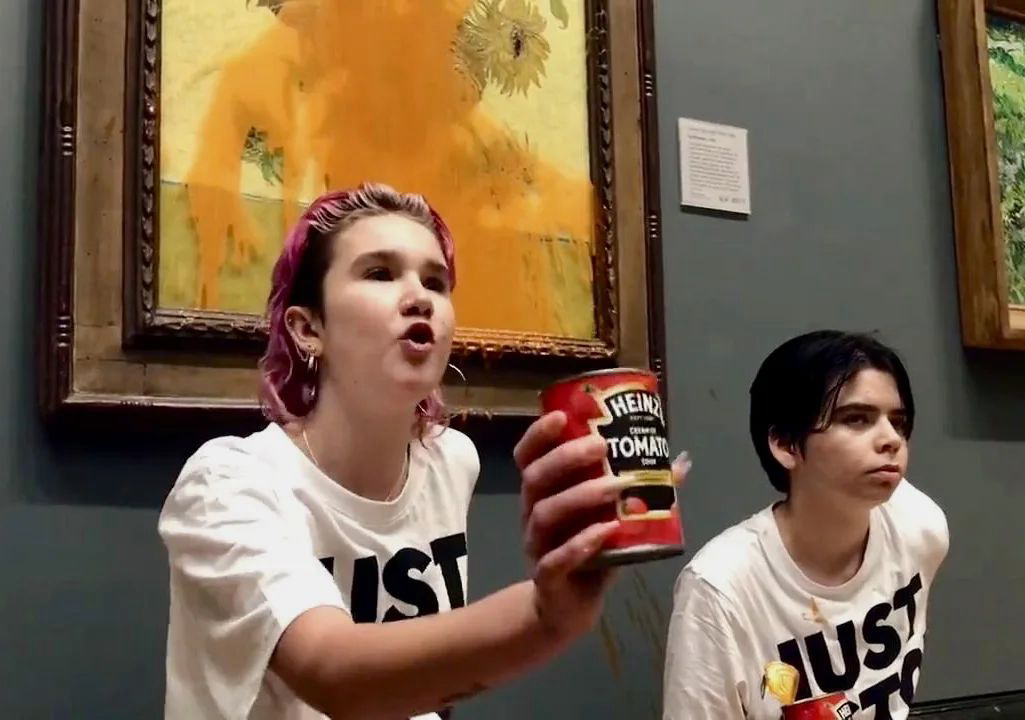

Last month, after dousing Vincent Van Gogh's Sunflowers with a can of tomato soup, a climate activist reportedly asked a passerby, "What is worth more: art or life?" The internet responded promptly: "Art." One tweet, which collected more than 10,000 likes, referred to the incident as an act of “anti-human nihilism.” Another said of the activists; “Their message is clear: destroy beauty and civilization." But the online outrage only adds to the protesters's point—why are we more focused on human depictions of the natural world than we are on the daily destruction of those same landscapes?

The attack on Sunflowers by Just Stop Oil protestors took place on October 14 at England’s National Gallery. The demonstration was closely followed by a second episode, in which members of the German climate activist organization Letzte Generation (Last Generation) threw mashed potatoes at Claude Monet’s Grainstacks at the Barberini Museum in Potsdam. The events kicked off a string of protests in museums across Europe, with the aim of calling attention to climate change complacency. But in every case, the treasured artifacts remained unharmed—each historical gem is sealed behind protective glass.

Van Gogh and Monet were interesting initial targets for climate activists. Since the first two incidents, everything from Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earing to Francisco Goya’s nude portraits have been hit. But, Van Gogh and Monet were, in many aspects, landscape artists. They painted night skies, rolling hills, lilypads, and early evening light. Their work, now considered a hallmark of our shared cultural history, is preserved at great financial cost.

Buildings are erected to house the paintings of these masters. They are given tamper-proof glass, velvet ropes, temperature control, and guards on constant standby. To deface or damage their creations is akin to degrading what society itself stands for: that art must be considered sacred, and therefore deserves our investment. The same can’t currently be said for the natural landscapes that inspired such moving work. When Van Gogh’s starry night is blanketed by smog, or Monet’s water lillies shrivel in polluted waters, are the artists’s renderings of nature going to be enough to remember it by?

Despite the general agreement that something should be done about looming climate disaster, little substantial change has been enacted to prevent it, and the art world is not itself immune from such complacency. Earlier this year, climate group Culture Unstained made headlines for calling on the British Museum to cut financial ties with its sponsor BP. Only last month, the institution opened yet another exhibit funded by the oil firm. Stateside, a number of influential arts benefactors, including collectors Ken Griffin and Larry Ellison, have been named as top contributors to conservative politicians and groups, who have historically been unsupportive of environmental protections.

Creating art and then destroying it in protest is nothing new, at least not since a suffragette took a meat cleaver to Diego Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus in 1914. A century later, the act is no less shocking. It's part of what makes the strategy so successful. Starting in 2018, activist groups scattered pill bottles through the Met, pamphlets through the Guggenheim, and stood in the pool outside the Louvre, all in the name of getting the institutions to cut off the Sackler family, who own Purdue Pharma and whom many credit with helping to create the opioid crisis. In 2019, the Louvre was the first domino to fall, removing the Sackler name from the museum, and was followed by the rest of the international art community.

In the late '90s and early 2000s, there was another rash of splatterings. It was fake blood instead of tomato soup, expensive furs and couture instead of paintings. Back then, PETA got the public to care about ending the sale of furs by targeting wealthy coat owners, and walking on runways in the nude. In 1994, the group stormed the Calvin Klein offices and spray painted the walls. After Klein himself sat down with them to watch a graphic video of the fur-collection process, he announced that the brand would no longer sell the product. It was through these attention-grabbing stunts that PETA infiltrated the public consciousness, driving anti-fur sentiments that ultimately shifted the industry.

Art’s inherent vulnerability, relying on its caretakers for preservation, is part of its magnificence. How could something so powerful in the cultural imagination be so frail in actuality, that a painting could be ruined by a slight change in temperature or cigarette smoke? The Earth is no less in need. It has no glass barriers, no ropes or safety cones. It is made to be trampled on and dug into. Its guards, it would seem, have been distracted for several years. Despite the furor online, the paintings targeted remain unharmed, which suggests that the goal of such demonstrations is less to create lasting damage than to prevent it.

in your life?

in your life?