When Austyn Weiner gets on the phone ahead of the opening of her latest exhibition, she’s sitting cross-legged in the gallery, her floral paintings towering over her from all sides. The works compose “Half Way Home,” on view through June 21 at Lévy Gorvy Dayan in Manhattan.

The press release notes a Musée de l’Orangerie exhibition of Monet’s “Water Lilies” as an early source of inspiration, but such serene expanses feel like a far cry from the Los Angeles-based artist’s distorted fields of color. “My physical space, my studio, my studio neighborhood of Frogtown, the influence of the LA River, how much time I spend walking on the streets of LA, even the vastness of our highways, vandalism, graffiti—all of these things were entering my landscape,” she says. “That was my Giverny in a lot of ways.”

In the darker corners of the canvas, the artist’s emotional terrain also seeps in. While making this body of work, Weiner got married; then lost her father, close friend, and grandmother within the span of a few months. Flowers, which have long drifted in and out of Weiner’s compositions, became a constant in her life—abundant at her nuptials, absent at her father’s funeral (as is the Jewish tradition), and cropping up in the yards across her neighborhood. “I like to live with flowers at varying stages of their life,” she muses. “I like to watch them die, and then I like to live with dead flowers.”

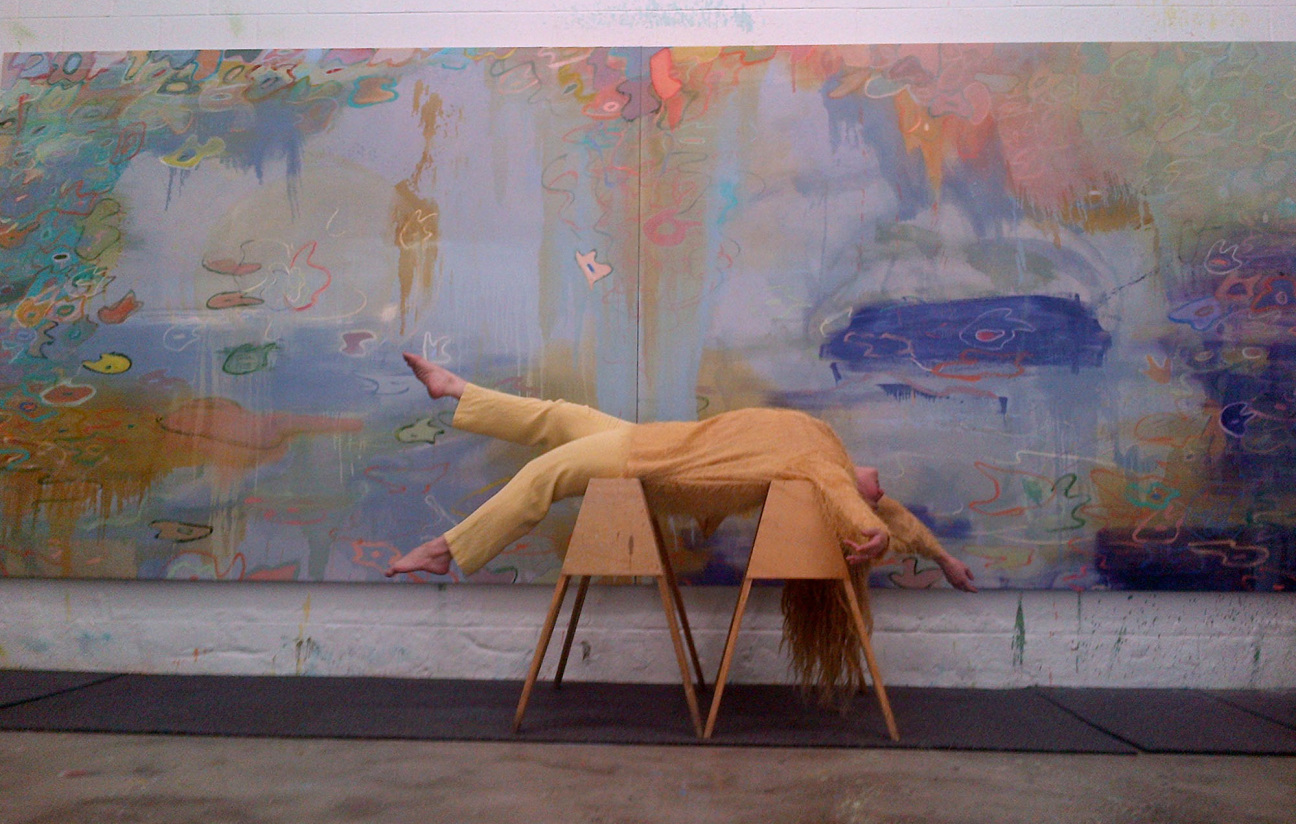

Prior to the opening of “Half Way Home,” Weiner ventured out across New York to collect blooms at varying stages of birth and decay. The spoils were arranged into a bouquet that stands in pride of place as guests enter the gallery. “Here they come now,” she says on our call as an assistant brings her array of blooming and withered florals into the frame. “I like to see what happens when they live together.” The fascination carries onto the canvas for Weiner, whose compositions come alive, wilt, and are revived as visitors turn through the space. To mark the exhibition’s opening, the artist offers CULTURED a glimpse inside her Frogtown studio, where she brought the show’s works to life.

CULTURED: Take me through your inspiration for this show.

Austyn Weiner: My flower forms began from sitting in the unruly, wild, and overgrown garden of someone very dear to me in the South of France. I was so inspired that I kept going back there for a decade and a half, just sometimes weeks on end, sometimes for months on end, drawing inspiration from this specific landscape. It wasn’t only the physicality of the garden; it was also the characters that flowed in and out of that garden.

There was a painting that I made in 2020, right as the world was shutting down. It was never seen, and it’s a survey of my mindscape in that moment in time. I never saw the painting again, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it for years. When I walked into this room [at Lévy Gorvy Dayan], it hit me that this is a room that could bring that work back to life for me. It’s like a lover that you never stop thinking about, even though years have gone by and you’ve moved past that moment. You’re a different person now, but you feel a need to, even if it’s just in your mind, re-explore what that relationship felt like. That sort of set the stage.

CULTURED: Flowers are so often thought of as this delicate adornment. What you’re going into seems to be a lot more about their life cycle—it’s a little macabre.

Weiner: For sure. In 2017, I had a show in LA called “Here’s Your Fucking Flower.” At the time, I was 26, I was single, and I was experiencing what most of us experience in our lives: the confusion and the dance of what it is to try to find love in and trust another. At that moment in my life, I was so resentful of flowers—and the implication that they could somehow make it all better.

I had this resentful relationship with flowers—like, God, I love you so much and I also fucking hate that anyone would think this is enough. I [was] exploring how something that brings me so much joy when picked, which technically begins its death cycle, was then used to console my own emotions. I wanted to explore all the ways a flower represents varying emotions and their changing symbolism throughout one’s life. This year, I got married, which is probably the most over-the-top use of flowers that exists in our culture, and the loss of my father weeks later. Within a few weeks, I saw this wild arc of the role of a flower.

With my wedding, I was so intentional about every type of flower and the ways they were installed. With the loss of my father—in the Jewish religion, you’re not supposed to send or have flowers as part of a funeral. I became resentful of that, because I needed sunflowers in that moment. I was fucking sad. That tension is something I will forever explore.

CULTURED: Is there a first thing you do when you enter the studio right off the bat?

Weiner: I get on that foam roller and I hit my bands. I’m warming up my shoulders, and I’m hanging on my scaffold, and I’m getting in my physical body so that I can embody the physicality that I wish to see in the paintings.

Over this year, I’ve created a kind of altar where I take a moment to acknowledge the pivotal figures in my life whom I’ve lost recently and through the making of this show. I say good morning to [them] and sort of thank [them] for the opportunity in my life, for being given this gift of creating.

Finally, I feel out which direction I want the music to take me that day. I’ve realized over time that what I listen to greatly affects my mindscape.

CULTURED: Is there a studio rule that you live by?

Weiner: I leave it all on canvas. I’m trying to exercise this further, so that between my personal life and my work life, there are as many definitive lines as is possible. I try to leave it all on canvas and energetically wipe myself clean before I step into my home and my other sacred spaces. My studio is a container for everything I am, without judgment. But when you step back into the world, you have to learn containment. That’s a journey I’m on. The one thing I’m deeply committed to is being a forever-evolving, forever-changing being. I feel free from this moment. I feel free from the past 10 years.

in your life?

in your life?