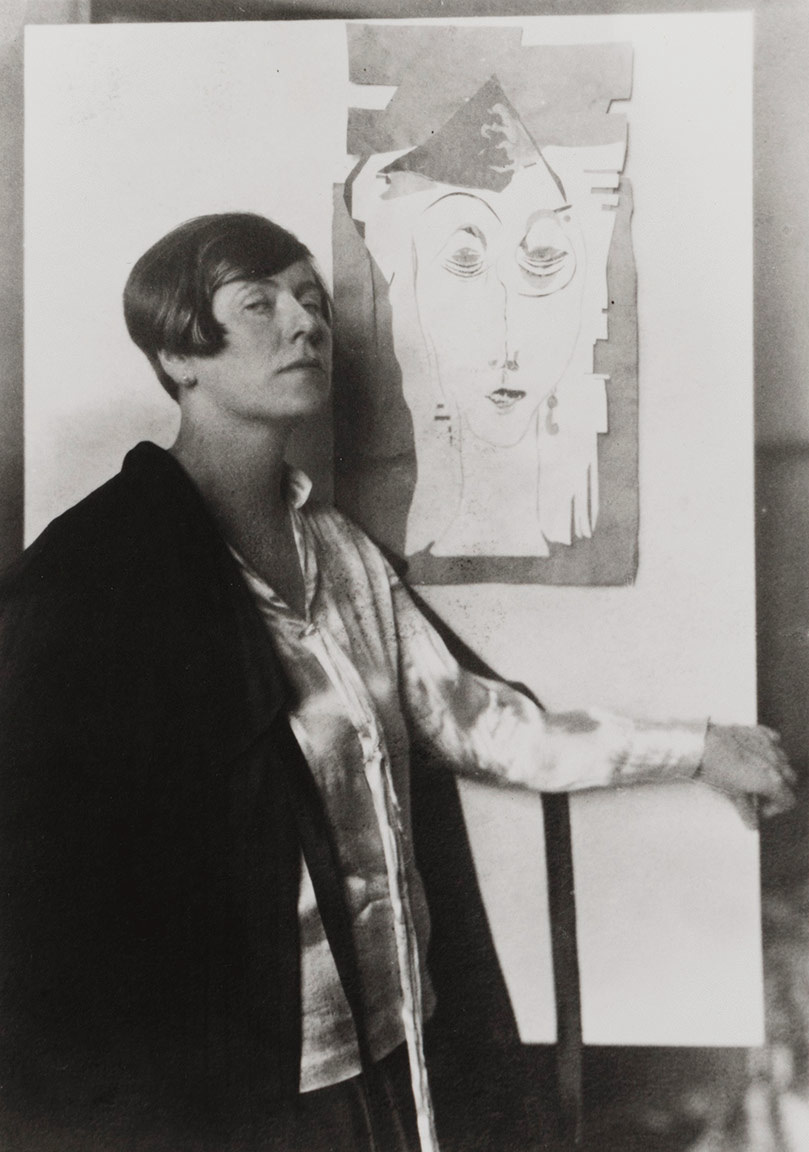

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum has housed masterpieces of impressionist, modern, and contemporary art in New York since its founding in 1939, and is famous for its swirling architectural presence designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Lesser known is the woman who inspired its creation and pushed for the utopian concept of objectivity that influenced its configuration: German baroness and curator Hilla von Rebay, who was allegedly at the center of a torrid love triangle with the museum’s founder and one of its most prominently featured artists.

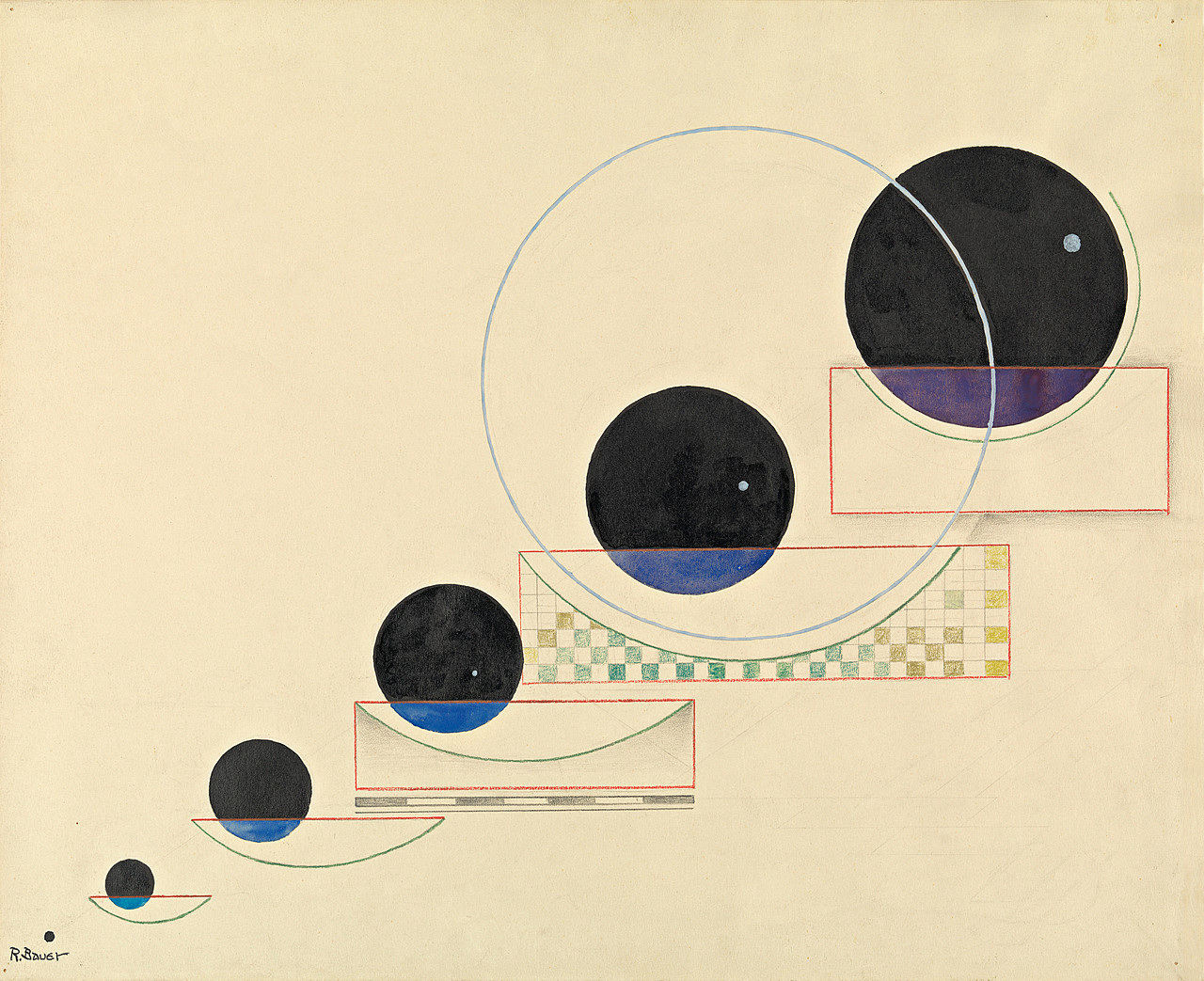

Born into German aristocracy, Rebay was exposed to art early on and demonstrated talent in the field, especially in portraiture. Her sketches were displayed in a group exhibition at the prestigious Galerie Der Sturm in 1917, where she met Rudolf Bauer. She formed an instant and passionate bond with the abstract painter, who was well-regarded for his talents, and was once arrested by the Nazis for his “degenerate” works during a brief return to his home in Germany. Throughout her life, Rebay remained his enduring champion.

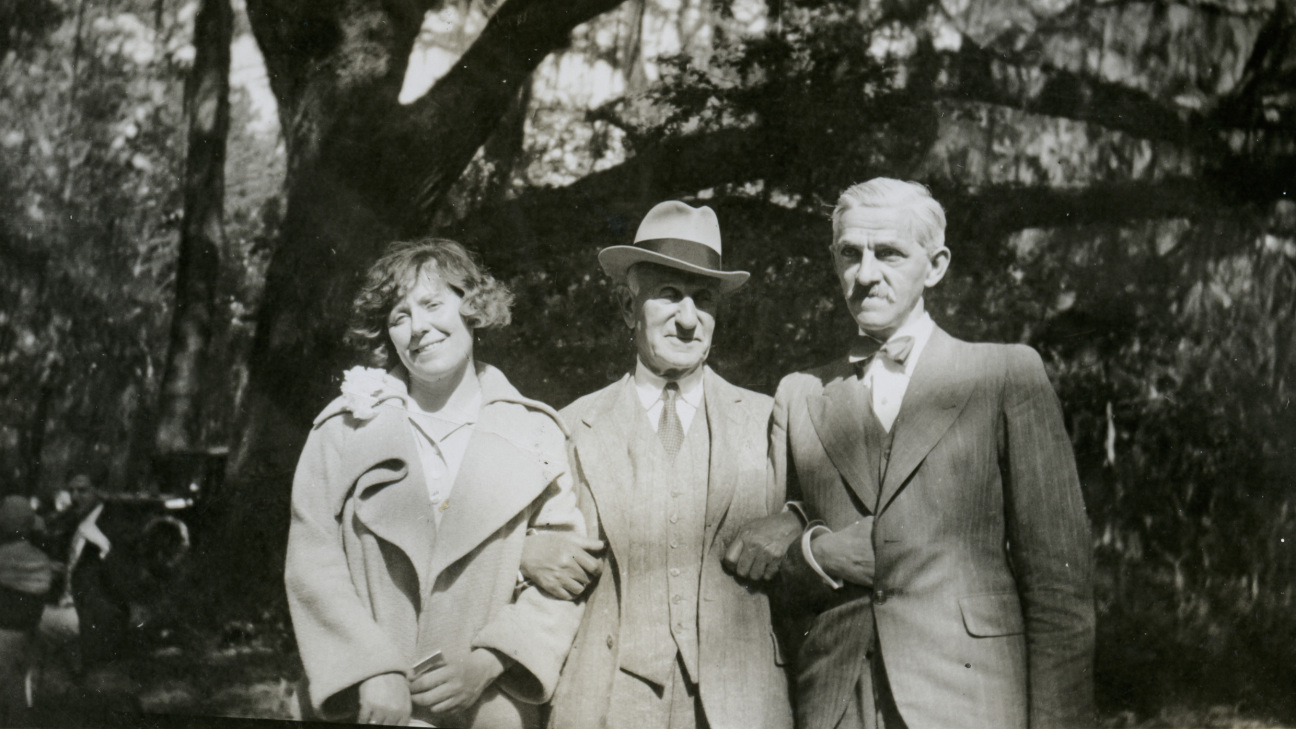

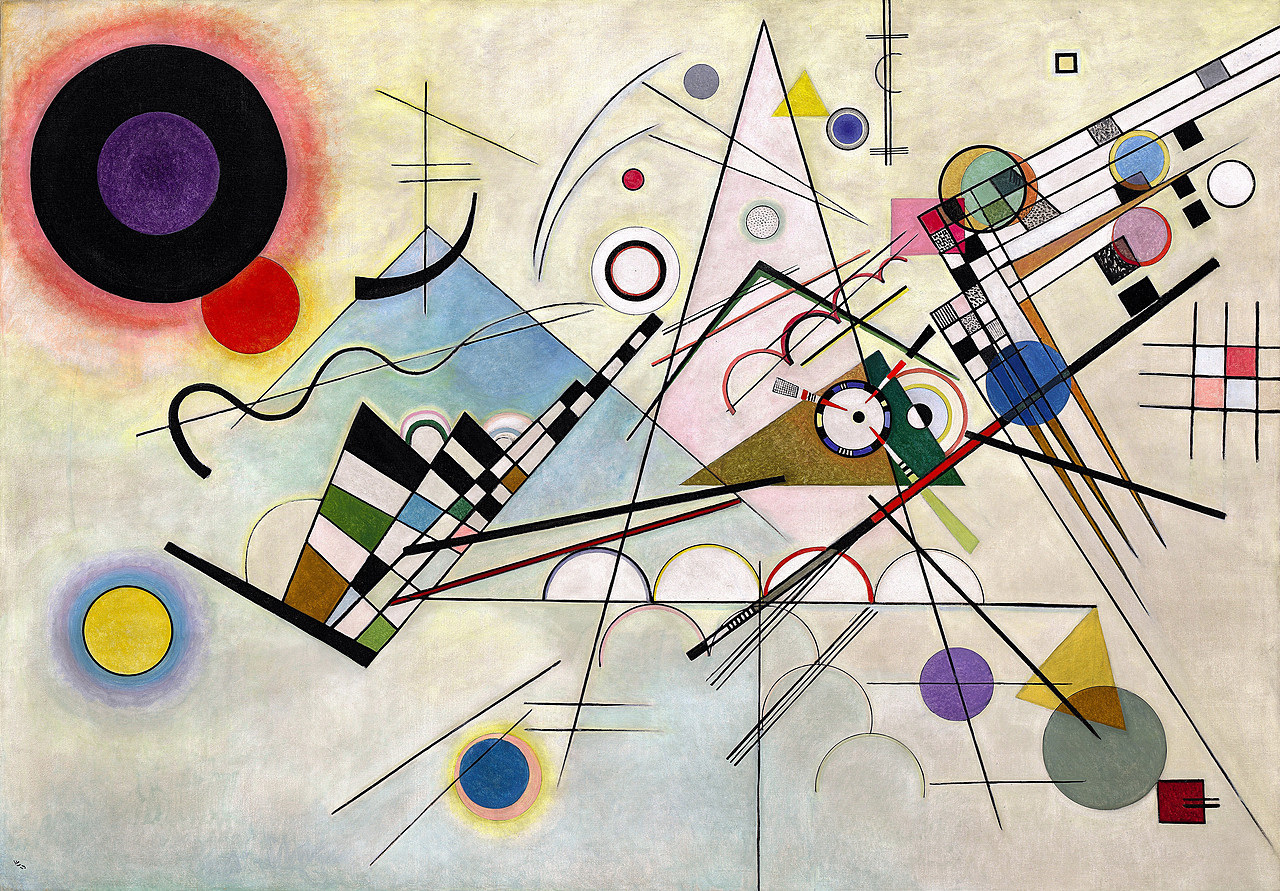

Nearly 10 years after encountering Bauer, Rebay immigrated to the United States and was commissioned to paint the millionaire business magnate and art collector Solomon R. Guggenheim. While he sat in her apartment, he noticed Bauer’s paintings lining the walls. Seeing that he was intrigued by their geometric style, Rebay convinced Guggenheim to purchase a few pieces. The meeting sparked a friendship and working relationship between the two, further developed a couple years later when Rebay accompanied him and his wife, Irene, on a trip through Europe. It was there that they met Wassily Kandinsky and purchased his piece, Composition 8, 1923, which remains in the Guggenheim Museum’s permanent collection.

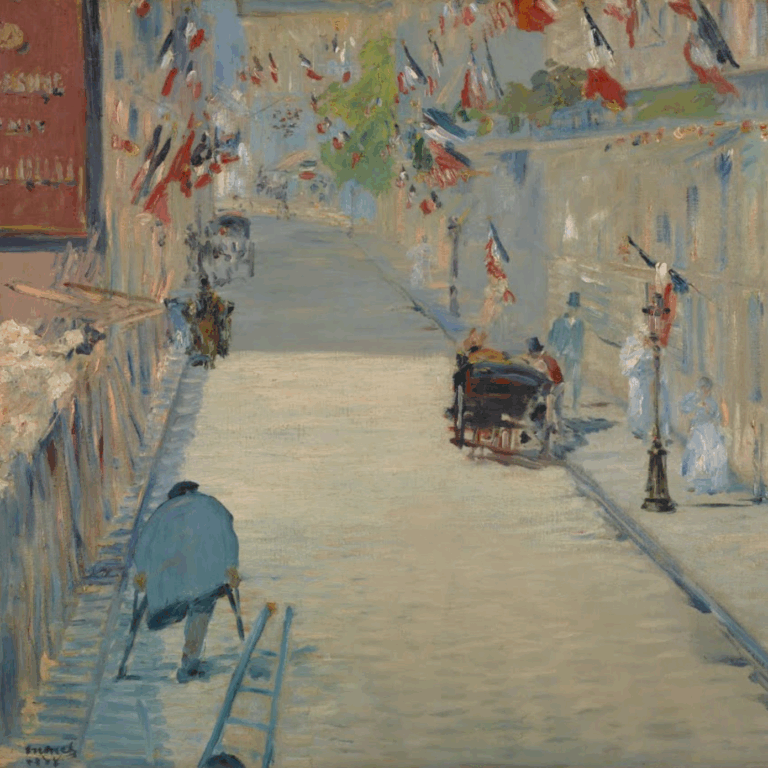

Rebay’s spiritual nature inspired a fascination with the geometric style of non-objective art. She believed it would be the religion of the future, claiming in 1937 that “the nations on earth will turn to it in thought and feeling and develop such intuitive powers which lead them to harmony.” Guggenheim, rumored to have taken the curator as his mistress, bought into her dream, and the two opened up such forward-thinking exhibitions around the country for several years.

By 1939, Rebay had convinced him to fund the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (the Guggenheim Museum's earlier iteration), where she served as the curator and director and featured a vast collection of work by her other lover, Bauer. The East 54th Street space was outfitted with aesthetic in mind; incense burned in the air and sounds of Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven played in the gallery. As the public’s fascination with the project grew, Rebay and Guggenheim commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the Guggenheim Museum’s location on 5th Avenue.

When Guggenheim died in 1949, his wife and nephew took control of the entity and unceremoniously removed Rebay from her position as director, demoting her to an advisory role, although the museum’s website states that she resigned. The two then reconstructed the institution’s vision, eliminating Bauer’s colorful and geometric pieces in the process. Despite his artistic gifts, Rebay’s undisguised enthrallment with the painter made him an easy target for a family looking to dial back her influence.

The curator continued to paint and collect art in her home in Connecticut. When she passed in 1967, the art in her estate, including a vast collection of Bauer’s work, joined the permanent collection at the Guggenheim Museum. Once all living remnants of their incestuous work-life relationship had vanished, the innovative curatorial vision Guggenheim, Rebay, and Bauer had forged was welcomed back into New York’s high society, where it remains today.

in your life?

in your life?