Hollyhock House, Frank Lloyd Wright’s first building in Los Angeles and one that paved the way for all of his Mayan-inspired, concrete-block homes in the city, has a spectacularly troubled history. He was commissioned to build the hilltop house by the avant-garde theater producer Aline Barnsdall, who had a fierce sense of her own style and the confidence to advocate for it. And once construction began in 1919, the two found themselves at odds over cost overruns–so many that Wright sent his Chicago-based employee R.M. Schindler to LA to take over as foreman. Made mainly of clay blocks because concrete proved too expensive, the house was completed in 1921, but Barnsdall never really settled into it and ended up gifting it to the city in 1927.

Now the house, beautifully restored and open to the public, is the site of “Entanglements,” a thoughtful and sensual collaboration between wife-and-husband artists Louise Bonnet and Adam Silverman, open through May 27. “We looked at the history of the house and its entanglements—there are so many pulling-pushing stories in this house,” says Bonnet during a site visit. Silverman adds: “A lot of the work we made physically embodies the idea of two people, or forces, coming together into a single thing.”

“Entanglements” is billed as the pair’s first "formal” collaboration—since marriage is, of course, a high-stakes collaboration itself, and raising children together is yet another. But throughout their decades-long careers, the two artists have kept separate studios, shown at different galleries, and have never worked on a major exhibition together. For this site-specific project, which they proposed to Hollyhock House curator Abbey Chamberlain Brach in 2022, Bonnett and Silverman worked independently on their contributions while making visits to the house together. “It’s such an opinionated house and our work can also be very assertive, so we didn't know how this three-way conversation would turn out,” says Silverman.

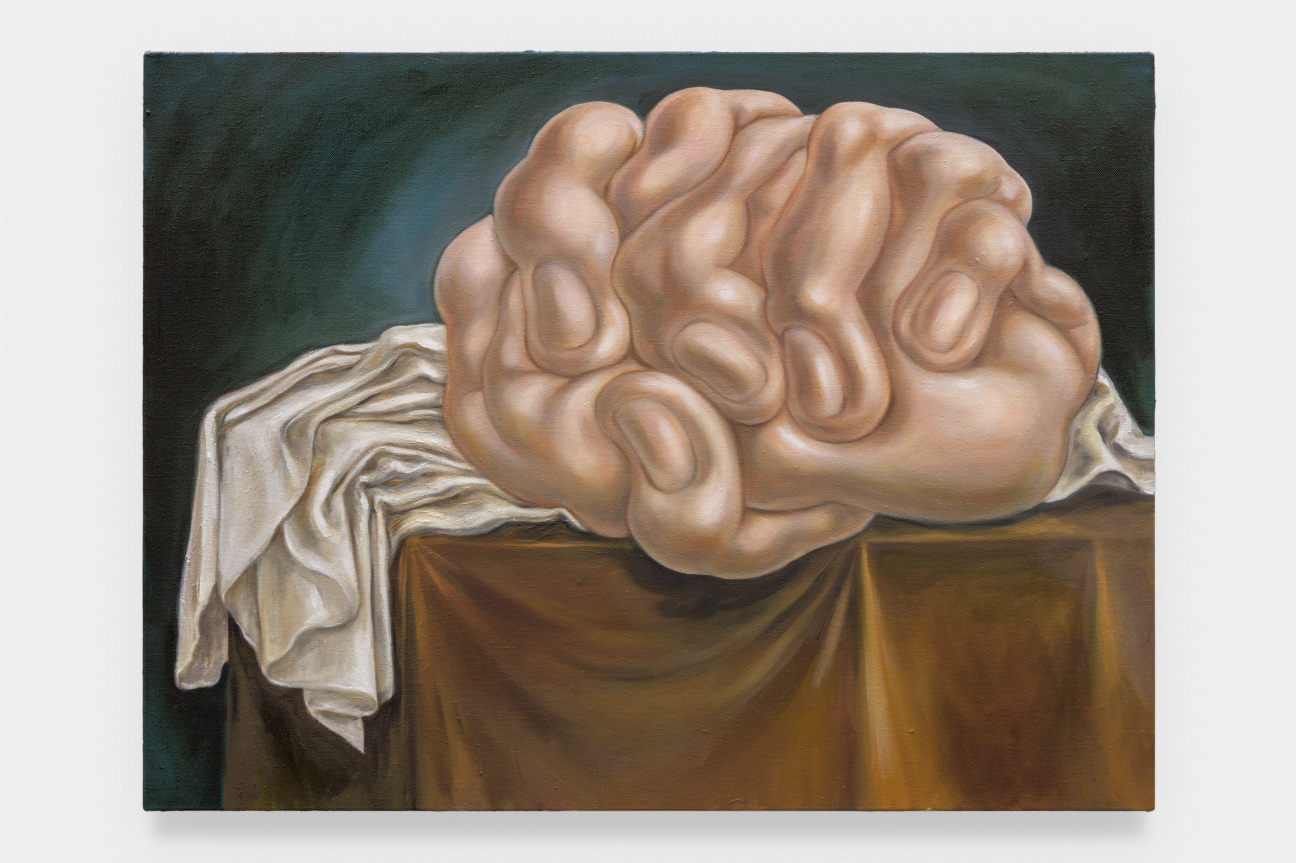

Best known for painting impossibly elastic bodies with the textured realism of the Old Masters, Bonnet created images of tightly intertwined hands for this project that could be seen as evidence of an embrace or a struggle. (Two are oil on linen; one is colored pencil on paper.) The hands are all set against a richly painted backdrop of draped fabric, a nod to Three Dancing Nymphs—a Roman marble relief depicting three women clutching one another’s voluminous garments, which Barnsdall had proudly installed across from the house’s main entrance. The fingers on Bonnet’s painted hands have so many extra joints they evoke the folds of the brain, extending this drapery motif. (One sign that the painter works from imagination, not photographs: her figures occasionally end up with an extra digit or limb.)

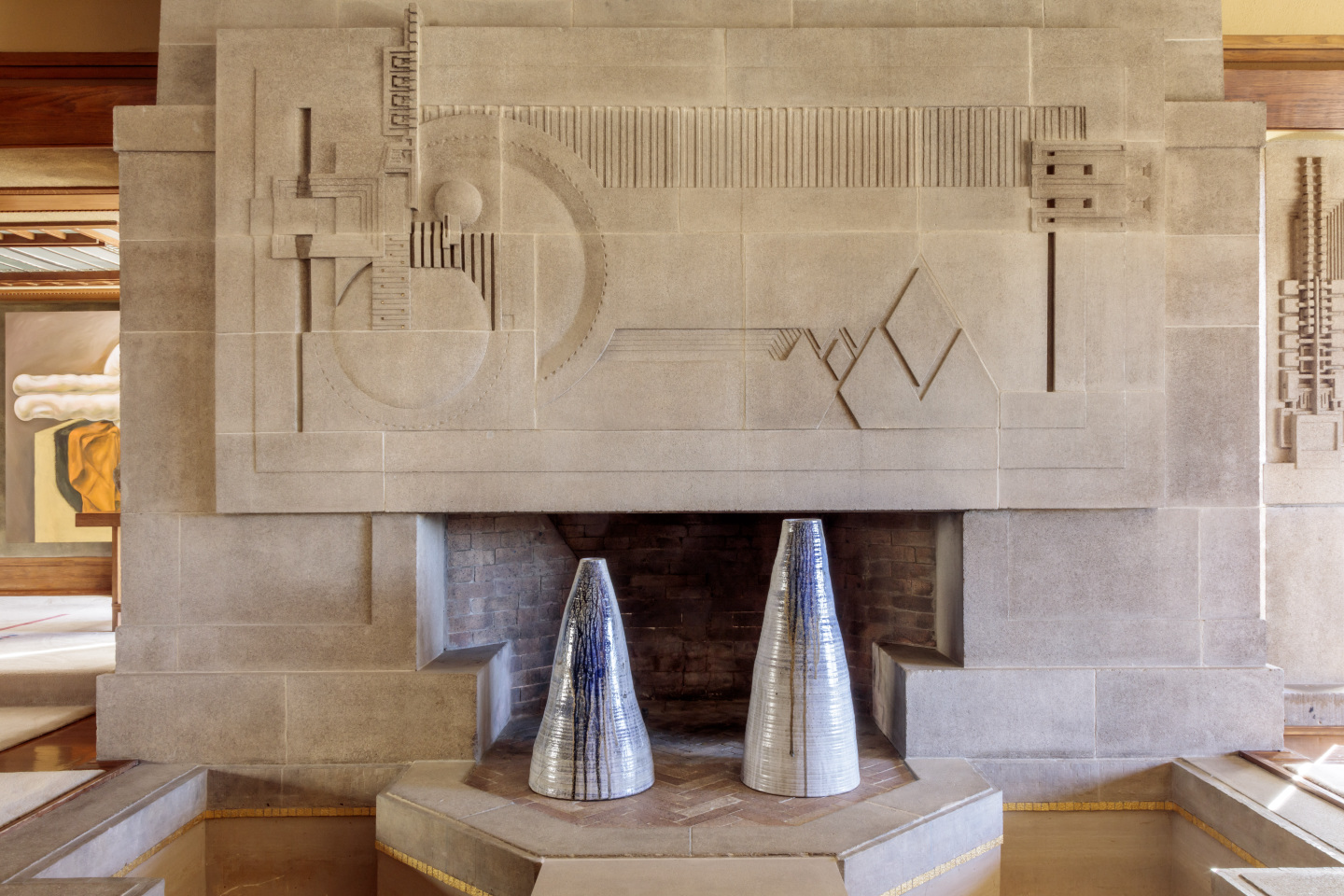

Silverman, for his part, has installed eleven of his ceramic works in different spots throughout the main living and dining spaces, including a pair of cobalt, cone-shaped vessels standing handsomely in front of a cast-concrete mantelpiece that is considered one of Wright’s greatest artworks: a bas-relief geometric design in the spirit of Léger and other machine-age artists. But most of Silverman’s pottery on view, some of which incorporate ash from the wood of the olive trees on-site, are uneven or eccentric in shape, playing up the organic references in the home such as leafy Japanese screens. The biggest surprise: five of Silverman’s pieces at Hollyhock House feature two or more pots fused together, like a child clinging to a parent.

The fusion first happened by accident, Silverman says, recalling a 2018 attempt at a kiln-loading method called “tumble stacking” that failed dramatically, leading some pieces to stick to the walls of the kiln and others to weirdly melt together. This time, he decided to pursue those failures in earnest, creating a motley assortment of two and three-headed clay creatures that seem to take their cue from the impossible figures in his wife’s paintings. Silverman and Bonnet have long shared an interest in lumpy, weighty forms, but this might be the first time one can see—thanks to the push-and-pull of their relationship and the back-and-forth of their dialogue with Hollyhock House—an undeniable family resemblance.

in your life?

in your life?