This is Art History, your weekly primer on the art world’s salacious past. From heists to heartbreaks, CULTURED brings you the most scandalous stories from the history books, guaranteed to dazzle your dinner companions

There is a satisfying component to watching a con man pull off a successful trick—it requires a level of skill, cunning, and oftentimes a motive that others can empathize with. Films like Ocean’s 11 continue to dazzle audiences with endless remakes. Anna Delvey, who made her big break by convincing New York’s elite that she was a German heiress, is only the latest, real life iteration of this sensationalized duality. Despite being on house arrest, she’s locked in a new reality series and continues to reap the rewards of her Netflix dramatization, Inventing Anna.

Lesser known is Han Van Meegeren, a 20th century con man with his own exacting set of skills. Overlooked as a young artist, Burlington Magazine recorded Van Meegeren’s late-career confession that, “spurred by the disappointment of receiving no acknowledgments from artists and critics….[he was] determined to prove [his] worth as a painter by making a perfect seventeenth-century canvas.”

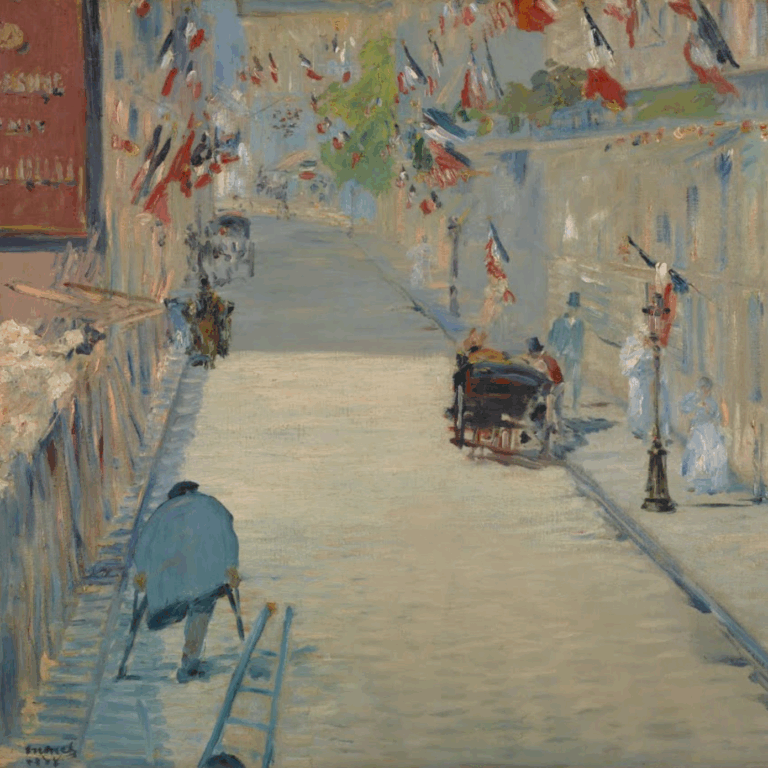

Whether out of spite or desperation, Van Meegeren abandoned his dream of finding personal, artistic acclaim and devoted himself to the recreation of others' work. He became a master of the baroque style, eventually able to accurately mimic even the most renowned painters.

Sources suspect that Van Meegeren spent close to six years perfecting his technique to successfully fabricate Johannes Vermeer’s artwork, before creating his most esteemed pieces in 1937. Initially, he faced challenges with the aging process; oil paint can take centuries to harden the way Vermeer’s authentic works already had. Driven by his desire for revenge upon his detractors, the forger discovered a way to pass the tests by mixing his paint with a synthetic resin rather than oil. Once the painting was complete, he would bake it in an oven, which hardened the canvas and gave it a cracked appearance.

To further conceal his identity, Van Meegeren focused on an earlier, amateur period of Veremeer’s career from which no pieces were known to have survived. His resulting work didn’t merely pass as Vermeer—it added to the deceased painter’s legacy. Abraham Bredius, one of the most acclaimed art historians of the time, referred to Van Meegeren’s 1937 painting, The Supper at Emmaus as, “a hitherto unknown painting by a great master, untouched, on the original canvas, and without any restoration, just as it left the painter’s studio.” Bredius, who dedicated his life to the study of Vermeer, branded this painting as, “the masterpiece” of the original artist's oeuvre.

The forgery artist also created faux versions of various other esteemed Dutch artists, including Pieter de Hooch and Gerard ter Borch. His most notable deception involved Hitler’s right-hand man, Herman Göring, a dangerous play for the daring con man. Van Meegeren's career ended when Allied Forces traced Nazi Alois Miedl’s Vermeer painting back to Van Meegeren in 1945. The forger was arrested and charged for collaborating with Nazis by selling them cultural treasures. Van Meegeren rejected this claim, instead positing that he was, in fact, a hero for fooling Nazis into buying fakes. He further argued that his painting Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery had been exchanged for close to 150 pieces from Göring’s stolen art collection.

Beginning in 1947, Van Meegeren’s trial dragged on for two years in the Regional Court of Amsterdam. Locked within the courtroom, he agreed to create one last forged Vermeer titled Jesus Among the Doctors live before the audience. What followed was a flawless recreation of Vermeer’s signature style, thereby proving to the breathless court that he had indeed conned the Nazis. He was, of course, still sentenced to prison time for forgery and fraud, where he passed away from a heart attack before his sentence even began.

Van Meegeren’s twisted saga highlighted the art world’s enduring desire to answer remaining questions about a bygone artist with the bits of themselves left behind in their remaining work. Perhaps that’s part of the reason artists often reach the peak of their careers after their demise—the less accessible they are, the more riveting the archival evidence left behind. Van Meegeren’s elaborate trick relied primarily on leading the artistic community to a gift they most ardently desired.

in your life?

in your life?