This week, Art Basel Miami Beach celebrates its 20th anniversary. Arguably, the sexiest, most high-profile fair of the Americas, the event anchors the Miami marquee of art and design. Hosting thousands of collectors and cultural luminaries to experience countless works by the world’s most thrilling contemporary talents, it also secures the city’s premier year-round art status. As the expanse of paintings, sculptures, and general glitterati at ABMB can certainly overwhelm, CULTURED highlights six artists from this year’s anniversary edition that are propelling their mediums forward. From figuration and fiber to abstraction and installation—here is who to see at the fair this year and watch for in 2023 and beyond.

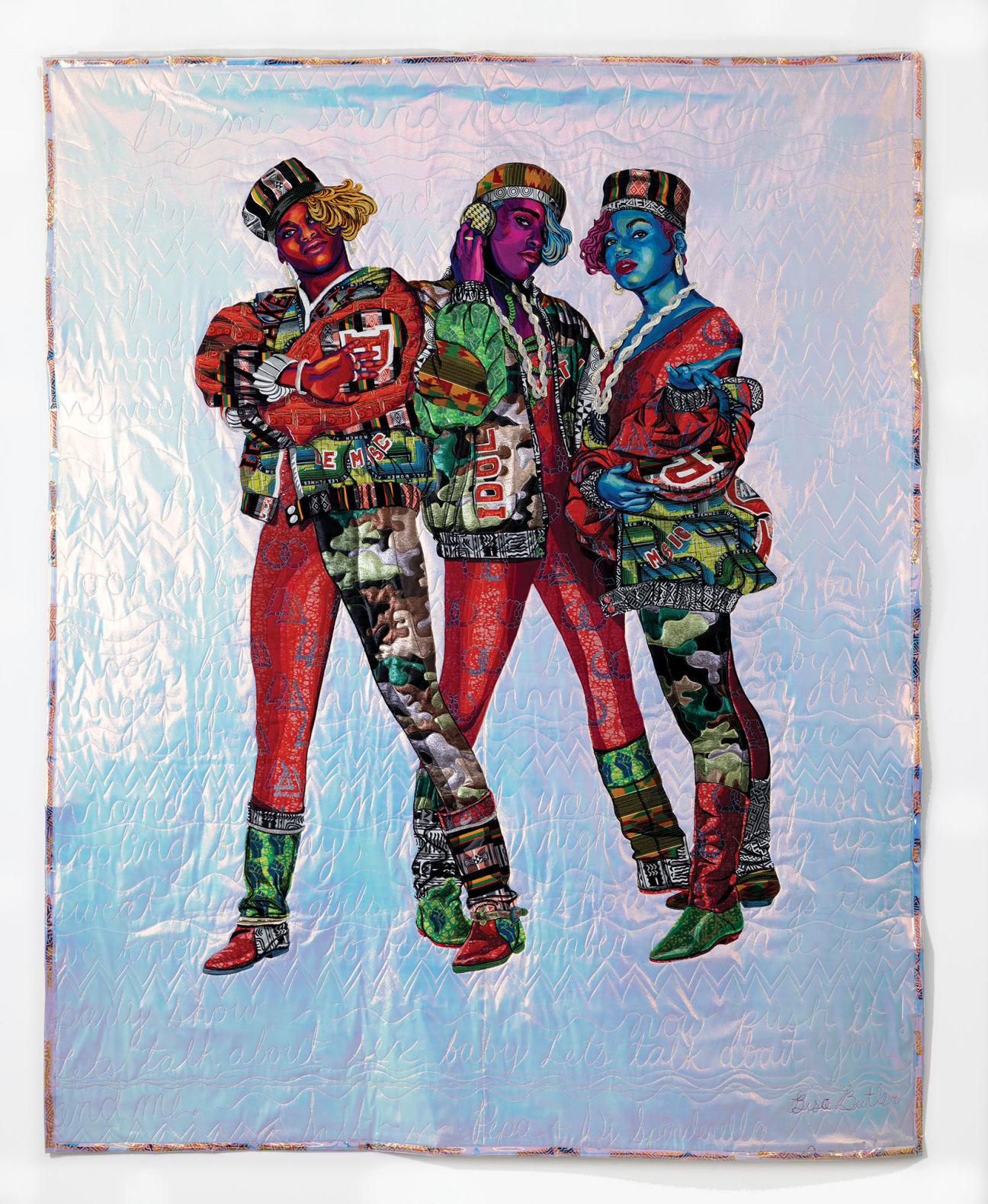

Bisa Butler

Jeffrey Deitch

“I am drawn towards images of people that project innate dignity,” Bisa Butler tells CULTURED of her process. “I research and save photographs that inspire me.” The artist, whose exacting, painterly textiles vault fiber arts into the future, is a recent Gordon Parks Foundation fellow and had a major solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2020 (its second stop after the Katonah Museum of Art). This week at ABMB, her fiery, iridescent Hot, Cool, & Vicious, 2022—in Jeffrey Deitch’s group presentation “Goddesses”—exemplifies her richly layered quilting, a hand-sewn amalgam of silk screened cotton, African and Dutch wax fabric, velvet, wool, and glitter.

“My husband suggested this photo of Salt-N-Pepa by Janette Beckman and when I looked at it, I knew it was the one to use,” she explains. “The three women stand like female gladiators, strong, fierce, and beautiful—nothing can stop them. They are hip-hop, they are feminists, and they are glorious.” Butler connected with Beckman, who, after agreeing to her image’s transformation, photographed the artist and her husband. “When people see my piece, I hope they can see my intentions,” Butler adds. “I want to express my admiration for what Salt-N-Pepa have done as trailblazers in the male dominated world of hip-hop.”

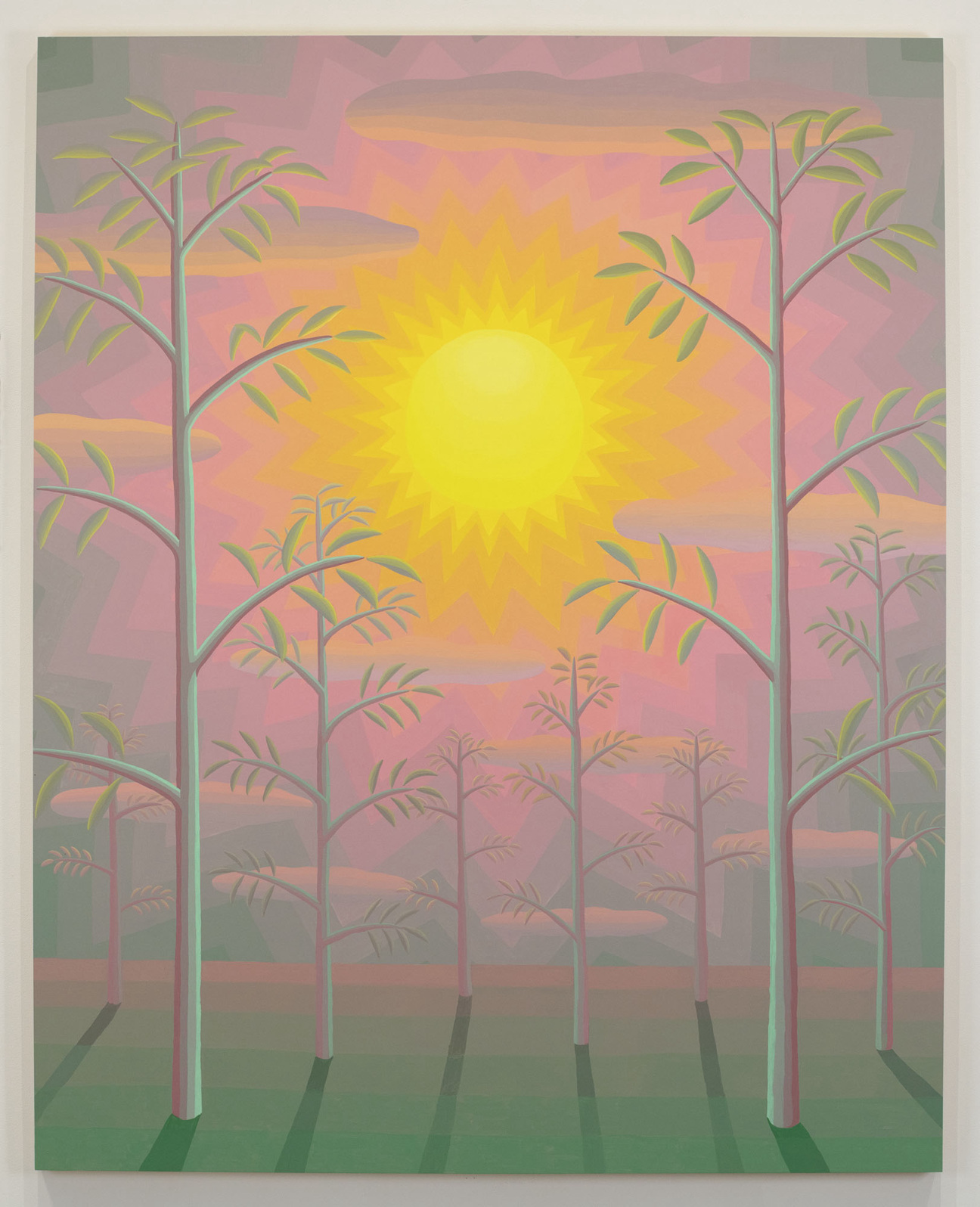

Amy Lincoln

Sperone Westwater

There’s no substitute for actually standing before Amy Lincoln’s sublime colorform. Her imagined abstractions evoke a wondrous world of wavy, celestial horizons and groovy foliage. “I’ve been exploring the idea of depicting water, sky, and celestial bodies in any possible color or combination of colors to see how weird the color could get while still referencing the peace and connection that I feel in nature,” she explains about her seascape paintings.

Indeed, Lincoln’s dreamy masterpieces blur the trippy and the serene. Her painting Radiant Sun With Trees, 2022, on view at the fair conjures newer tree imagery, alongside her signature sun motif, with its incandescent, zigzag gradations. “I want to experiment with color, but also determine how much the color needs to function to still feel like a tree,” says Lincoln—a must-see this week, ahead of her hotly-awaited spring exhibition, which will unfold over two floors at Sperone Westwater New York in early March.

Jesse Mockrin

James Cohan Gallery

Figurative painters have captivated the art market of late, but Jesse Mockrin stands out in a crowded field as a name to know now. New to the James Cohan Gallery roster, the LA-based artist mines details from Old European masters to reimagine the Western canon and the bounds of oil painting, all in a divine—and exceedingly contemporary—glory. Already in dynamic collections around the country—from the Los Angeles County Museum to the Rubell Museum—the artist is indelibly on the rise. “I visit art museums and look through books of historical paintings for inspiration for my work,” says Mockrin of her painstaking practice. “I then make small pencil drawings, focusing on the composition of the painting I might like to make.”

In Miami, she presents (for she died), 2022, which revamps Francesco Furini’s 1632 composition The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel. “I came across the original painting this summer while I was doing research for my upcoming solo show in New York next September,” says the artist. “It resonated with me at once because I haven’t seen any other historical paintings that depict birth. The risks that pregnancy and childbirth have always posed to women have been on my mind since the leaking of the Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade.” Mockrin crops Furini’s original to frame the mother's post-birth moments before her death with myriad attendants reaching for her. “All those hands felt like a timely metaphor for the intervention of others into the private lives of women,” she tells CULTURED.

Guillaume Biji

Meredith Rosen Gallery

“The concept of my ‘Transformative Installations' is that art spaces are taken over by more commercial fictive spaces—a supermarket, a travel agency, a car dealership, a shooting range, or, in this case, a casino,” says Antwerp-based Guillaume Bijl, known for pushing the readymade and found-object aesthetic through trompe-l'oeil situations. “Is it true or not? It’s a play between fiction and reality with the public. Because the art fair is an artspace but a commercial marketplace, I am restaging realistic gambling decor from capitalistic society that has a double expression.”

Reproducing Installation: Casino—which was first shown in 1984 at Friends Society of S.M.A.K. in Ghent, Belgium—introduces a fresh overlay to the artist’s replicas, a sly critique of speculative art-buying, the NFT eruption, our billion-dollar industry’s ascent in a pandemic, and ever-rising interest rates. “Like most of my work, it is tragi-comedy,” says Bijl of the copious detail: the carpet’s precise pile and lighting cadence—a croupier at tomorrow’s VIP opening, a tableau vivant in the artist’s parlance—evoke the seedy glamor of gambling on the convention floor. Presented by Meredith Rosen Gallery, Casino’s blackjack and roulette tables are a brilliant, tongue-in-cheek appraisal of art as consumer sport and Basel’s test of the elasticity of demand.

Richard Deacon

Marian Goodman Gallery

An influential fixture of the early-1980s movement New British Sculpture, Richard Deacon is forever avant-garde. The Turner Prize winner creates singular idioms through wood, stainless steel, clay, leather, vinyl, and leather. This week, Marian Goodman Gallery brings Deacon’s influential 1987 Double Talk—originally shown at MoMA PS1 in Queens, New York—to Miami. “The work could be described as an outlined mouth with a tongue, denoted by the red vinyl covering on one side and a speech bubble on the other side,” Deacon explains to CULTURED. “However, its large size means that the work dominates the space in which it is situated, as speech or language delimit our perceptions and frame our world.”

A self-described “fabricator,” the artist’s technical prowess playfully negotiates linguistic and visual syntax. “The relation of the loose sleeve to the structure—not tailored to fit, but merely a tube slid over the curve, crumpled on the inside to accommodate the bend—derives from questions that I had—and still do have—about the relation of clothes to the body,” he explains. “Or at a deeper level, of substance to appearance and of the relation of words to things.”

Dewey Crumpler

Derek Eller Gallery

Dewey Crumpler’s “Hoodie” paintings—intimate, metamorphic deliveries from an Afrofuturist cosmos—germinated from his children’s discovery of hip-hop. “I used to tell them to shut it off,” the artist explained in a 2021 interview with Sampada Aranke, professor of art history, theory, and criticism at the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. “I thought the music put them in danger of being perceived as thugs because it was constructed around misogyny-gangster rap and gang pathology.” Eventually, however, he found himself overtaken by the beat, and realized that his children were “reframing Blackness for themselves,” as he put it. “They were shapeshifting.”

The hoodie itself is a cloak—manifesting through time and space—and the figures don’t reflect us, insists the artist, but rather pure consciousness. Crumpler began his practice in the late 1960s San Francisco Bay area as part of a cohort of young, Black artists that attended weekly meetings at the home of Evangeline “EJ” Montgomery. It was the curator-printmaker who eventually led him to study painting in Mexico with muralists like Pablo O'Higgins. For the fair’s Kabinett sector, Derek Eller Gallery gathers decades of the artist’s spectacular “Hoodie” paintings—a series initiated nearly 30 years ago that couldn’t feel more prescient or powerful. “I was painting some new ‘Hoodie’ works yesterday,” he tells CULTURED on the eve of the ABMB. “Whenever they want to come into being, which is not always, I bring them.”

in your life?

in your life?