Gillian Laub

New York-based Gillian Laub has released a number of monographs—including Testimony, Southern Rites, and Family Matters—dissecting issues of race, media, and family dynamics. Here, she captured her family on Thanksgiving.

“Family is so rich in narrative. I love unpacking those intergenerational dynamics and relationships … My mom still does all the cooking—there’s always more food than we can ever consume. Her old handwritten recipes have gravy finger stains all over them. Every detail is important to her, down to the serving spoons … I will always photograph [my family]. There's so much humor in [them]—I just needed to take a moment to enjoy that.”

Roe Ethridge

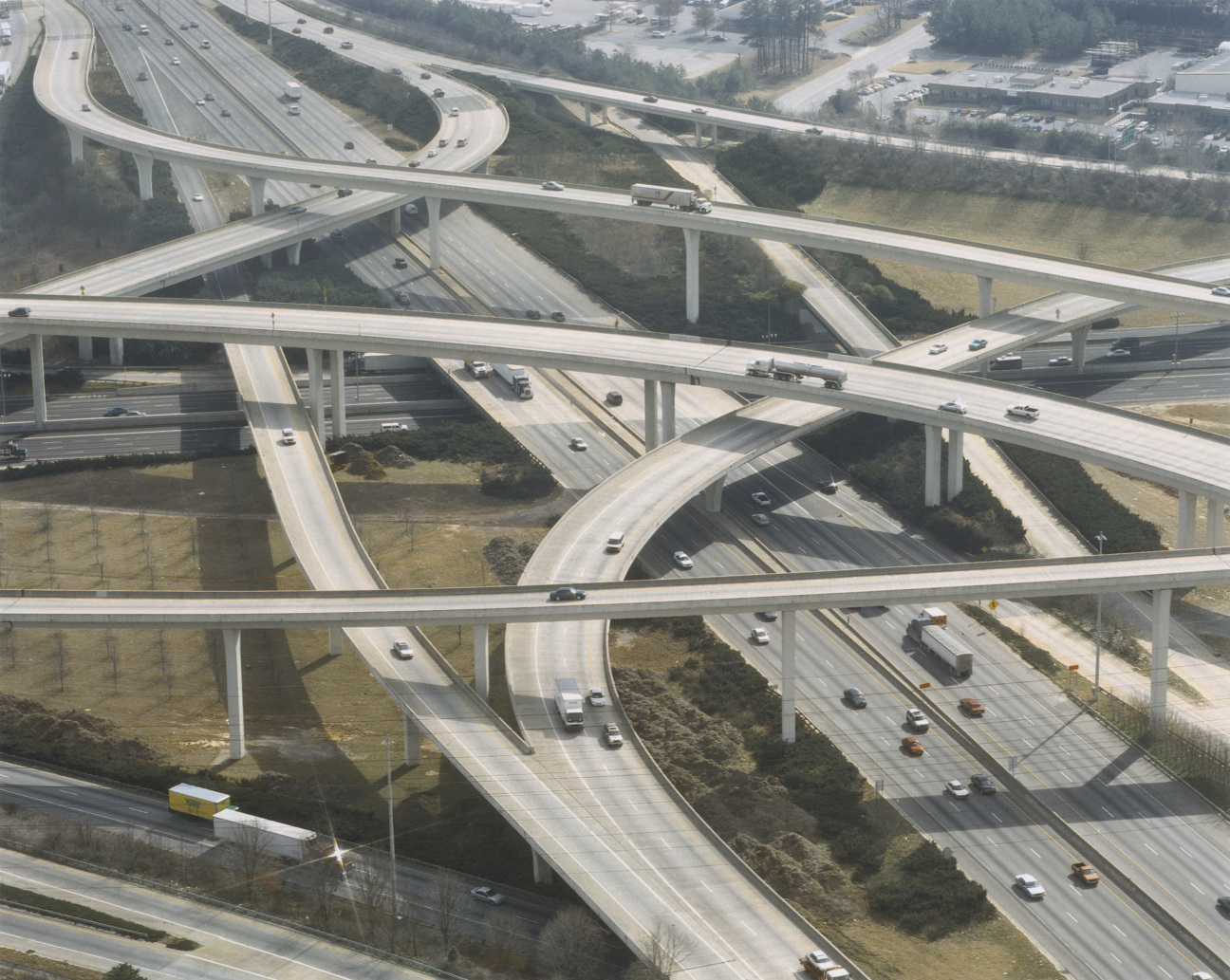

Roe Ethridge has, over the past couple decades, made work at the intersection of fine art and commercial stylization, following in the lineage of artists like Andy Warhol and Lee Friedlander. Here, he shares another important intersection from his oeuvre and most recent monograph, American Polychronic.

“American Polychronic is a kind of juxtaposition. America is monochronic in terms of how we spend our time. According to the Google search I just did, 'Polychronic means a culture does many things at once. Their concept of time is free-flowing, and changes depending on each situation. Distractions and interruptions are a natural part of life, and have to be taken in stride.’ That definition pretty much sums up how I would like my life and work to be. But I’m still a middle-class Methodist from the South. So…yeah. American Polychronic.

I love the South for its unhealthy food options and for the crazy contradictions and college football, etc. One could say that the South I depict is specifically generic and yet totally personal. The highway overpass—a marvel of tangled off ramps and flyovers known in Atlanta as Spaghetti Junction—is the same one that I had to navigate my first time driving to Karen Light’s house at 15 in a red Buick Skylark station wagon.”

Jesse Clark

Jesse Clark is a Haitian-American photographer and recent graduate of the Ringling College of Art + Design. Here, he captured the 4th of July, 2023 from Florida.

“I view the U.S. as a land that has provided me with a new chance at life. I was brought here from an orphanage in Haiti, so I recognize the privilege of the resources I have here to be able to live and express myself. Given what the U.S. has provided me, I understand there is much I have to give back, especially belonging to a younger generation. With that in mind, I see the camera as a tool that allows me to capture the beauty of my identity, surrounding community, and culture. I feel there are many stories and people I can document and highlight the existence of, to help move America toward positive change and unity.”

Jamel Shabazz

The Brooklyn-born Jamel Shabazz has captured the raw alchemy of street life across the world, but the 63-year-old photographer is best known for documenting the birth of hip hop in his hometown. Here, he reflects on documenting a Saturday night in Times Square during the summer of 1981.

“As a young photographer who was trying to get better, Times Square was the place to go. Back then, it was like Las Vegas for many young people. People from all five boroughs and the rest of the world would gather there to see a movie go to dinner, and just socialize … I spent pretty much the entire afternoon and early evening standing on the corner of 7th [Avenue] and 42nd Street.

When the trains came in, hundreds of people would get off who I wanted to photograph; I would pull them over and show them my portfolio and engage with them, and like that I built up a body of work. I found a lot of couples, and focused my lens on love, diversity, [and] people from all over the world. When I saw this group, I thought, Everything is there. The fashion is there, the friendship is there, the hip hop is there. It just represented everything to me.”

Tommy Rizzoli

Tommy Rizzoli has photographed for various brands and publications including Tiffany & Co., Adidas, and OnlyNY. Here, he captured New York under siege of wildfire smoke.

“The smoke made me slightly more hesitant to spend as much time outside as I normally would. Much of my life in NYC revolves around walking and biking, and taking pictures while doing those activities. This event, however, left people like, ‘Whoa this looks apocalyptic,’ especially Wednesday when the sky turned to a deep orange in the middle of the day. It looked like Blade Runner 2049.

Whether I'm shooting editorial/campaign work or street photography, I always want there to be a level of realness in my images: real happiness, real sadness, real anger. I am fortunate enough to spend a majority of my time photographing my friends too, especially for my editorial work. This means a lot of the time the emotions that show in my images are real and natural. This week was different mostly because I have asthma and felt like I had been smoking cigarettes the entire time I was outside.”

Lucia Bell-Epstein

Working in kitchens taught New York’s Lucia Bell-Epstein everything she needed to know about her favorite subject: the culinary world. She’s since shot for clients including Canyon Coffee, Nicholas Morgenstern, and Ellie Bouhadana.

“[I want] to shoot all the shit that you don’t want to see—a spill on the floor or someone’s hands cutting something … There were definitely moments where it was like, ‘You should put it down. This is not the time to be shooting a beautiful radicchio pickled-cherry salad, but it made me make stronger images because I had to be like, I only have so much time … Beauty is a hornet’s nest. I want my photos to be vehicles for collaboration, trust, and risk-taking. And I want the process to keep me attuned and honest.”

Derek Ridgers

For over four decades, British photographer Derek Ridgers has captured the rough edges of concerts, musicians, and their wildest fans. One late night in the ’80s, he turned his lens on the Cramps.

“This is three-quarters of the rock band the Cramps harmonizing into one microphone. It was Sunday, April 6, 1986. The weather was overcast in Deinze, which is in Belgium. I remember that day very well because our trip was written up in the U.K. magazine Time Out, and I shot this photograph on commission for them. I’d traveled there early that morning from London with a coach-load of rabid, rockabilly Cramps fans … The most challenging part of live rock photography, with a manual film camera, is trying to get the photos in focus. I found that, when I started, I was able to get no more than about 25 percent of my photographs really sharp. With a lot of practice, over 30 years, I managed to get that up to about 30 percent.

The Cramps were a truly fantastic live band—one of the best I’d ever seen. They didn’t take themselves too seriously, but they took the music very seriously. Poison Ivy was hugely interested in vintage guitars. She was a great rhythm guitarist and, I think, still cruelly underrated. In any case, they certainly weren’t an all-ages band. Lux Interior would sometimes disrobe and wag his weenie at the audience.”

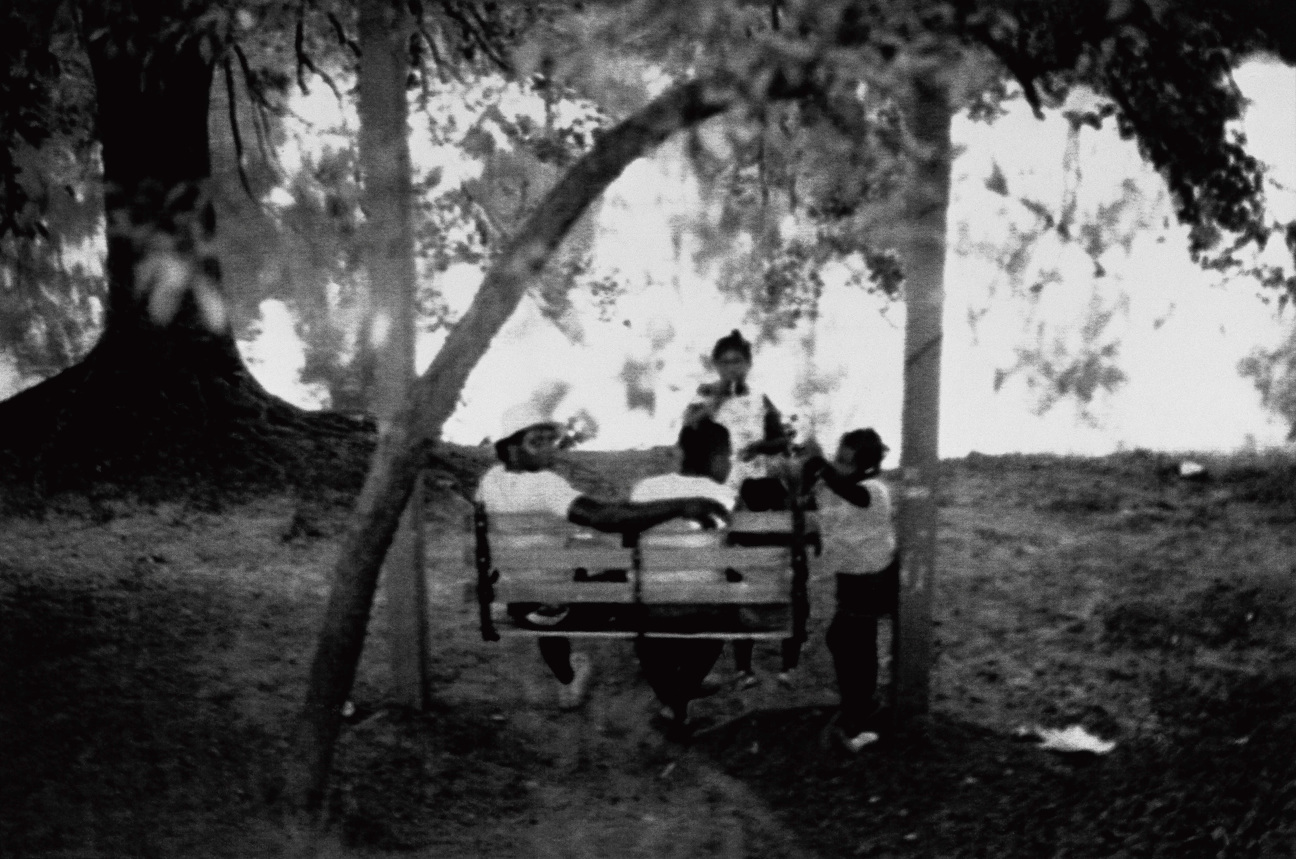

Ming Smith

Over a half-century-long career, Detroit-born, Harlem-based Ming Smith—the first Black woman photographer to have a work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art—has captured the auras of music legends. Here, she shared a testament to Black joy and family.

“I was attending this cool festival in Atlanta, Georgia, where a long list of musicians, including Kenny G, were performing … The Atlanta Child Murders [of 1979–81] were happening that summer. These were young Black boys—I think there were 28 of them at the time—who had been either strangled or stabbed or shot, and they were found not far from where they were murdered, in a park. It sent shock waves around the world, but the media was saying, ‘Well, it was tragic and everything, but these children didn’t have fathers.’ What does that have to do with it?

So when I saw this family, I was like, Look, there’s a father right there. You know, I shoot cultural icons—Tina Turner, James Baldwin—but this photograph was expressing something bigger, something totally sincere, something that was political, but beautiful. I love this image. I knew when I took it that it was a winner. Even without the history, it would have been a special one for me.”

in your life?

in your life?