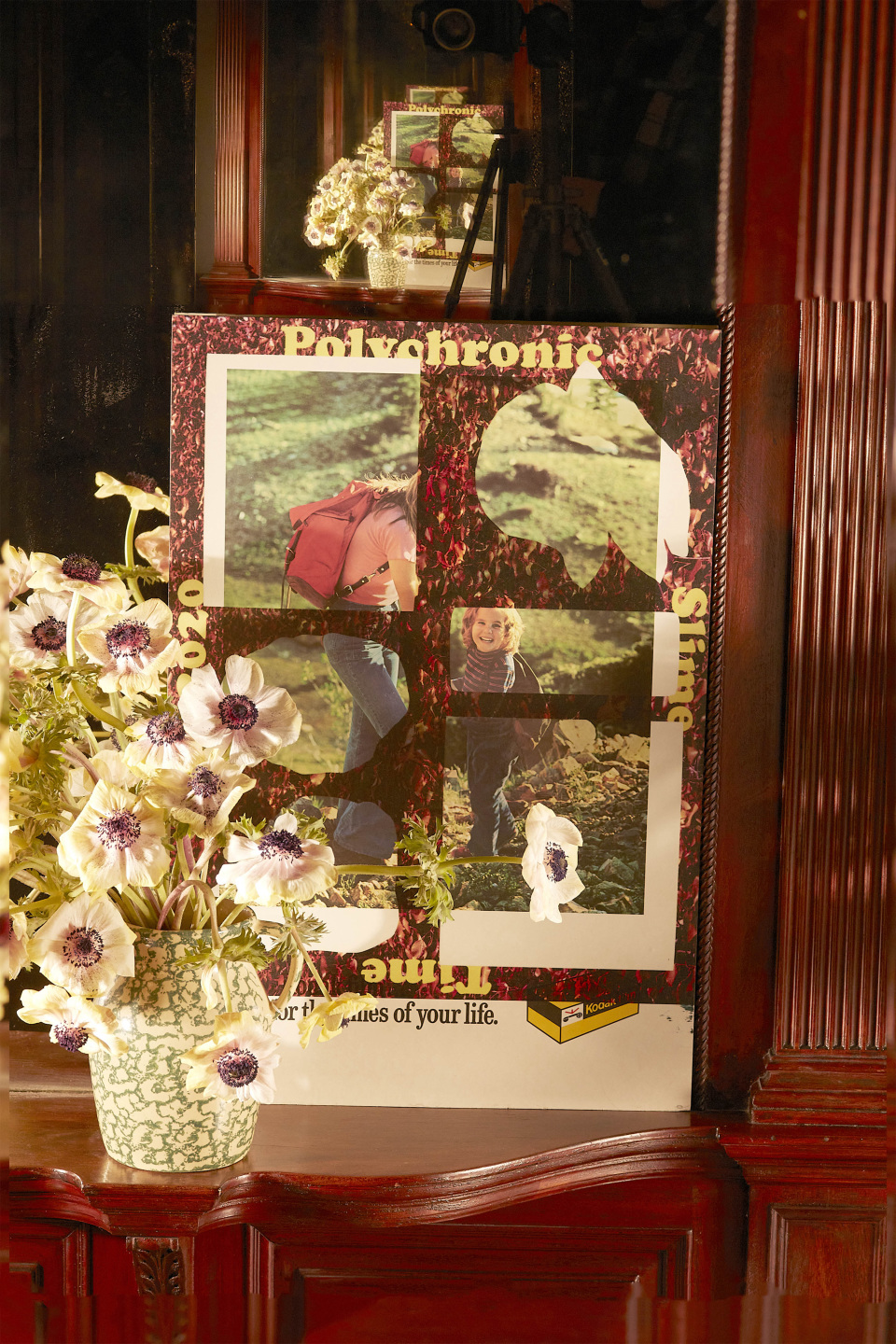

Jason Schmidt: Alright, so, what does American Polychronic mean? Or, maybe we should go more personal—before I actually met you, we were both printing at Print Space, and I saw one of those highway median landscapes pinned up on the boards. I thought I'm gonna like whoever took this picture, because it was something I’ve passed by a million times and would have never thought to take a picture of. What was that body of work called? Is it in the book? And what the hell were you thinking?

Roe Ethridge: The series I was printing when we met is called “Neutral Territory,” and was shot from 1996-1999!? It had pictures of trees on highway medians in Atlanta and around Brooklyn and Queens—what I had thought of as invisible places because we only see them when we drive by. I loved German New Objectivity photography at that time, and really wanted to make something typological. In the end, I think it got more romantic and personal and kinda went against the rules I had intended to follow. I also kept thinking about Ed Ruscha’s gas stations and J.G. Ballard’s Concrete Island.

American Polychronic is a kind of juxtaposition. America is monochronic in terms of how we spend our time. According to the Google search I just did…“Polychronic means a culture does many things at once. Their concept of time is free-flowing, and changes depending on each situation. Distractions and interruptions are a natural part of life, and have to be taken in stride.” That definition pretty much sums up how I would like my life and work to be. But I’m still a middle class Methodist from the South. So…yeah. American Polychronic.

JS: Southern Methodist—let’s go there! You grew up in Florida and Atlanta, and I used to jokingly (mostly) accuse you of playing up a southern aww shucks, I’m in the big city now kind of charm. But tell me how your background relates to your work, and maybe point us to some specific pictures in the book?

RE: This first one is me and my mom in our front yard on Wyntercreek Lane in August of 2021. The next is an image from Google Maps’s Street View of the house looking from the reverse angle of the picture of me and Mom.

JS: Good to see your mom again! We could do the rest of this conversation just on these eight pictures you sent through—they’re nuts! We’ve got self-portraits, landscape, still life, fashion, 4×5, 35mm, iPhone, screenshots, and I'm guessing a professional portrait of you at 6 years old. What’s the idea here? Lot’s of glossy surfaces and big smiles with the suggestion that below the surface all is not picture perfect? I mean you look unhappy and impenetrable in the shot with your mom and rather circumspect as a kid. Is that a fair reading?

RE: I was channeling an embarrassed, sullen teen vibe with my mom. Lee [Roe’s daughter] was taking the picture, so there’s a circuit there! Once I looked through the pics, I liked how she and I were in a sort of theatrical counterpoint, like a sketch for a movie poster (titled Oedipus of Wyntercreek Lane!?). The faded portrait of me in the plaid suit was made when I was 7 at Perrine Park in South Dade [Miami]. My dad made that picture. The sort of smile I’m giving there is very much like the smile my dad does when he’s getting his picture taken. I hadn’t consciously noticed that til just now.

JS: Why do you so often return to the South? It’s where you’re from, sure, but what is it about the South per se that matters to you?

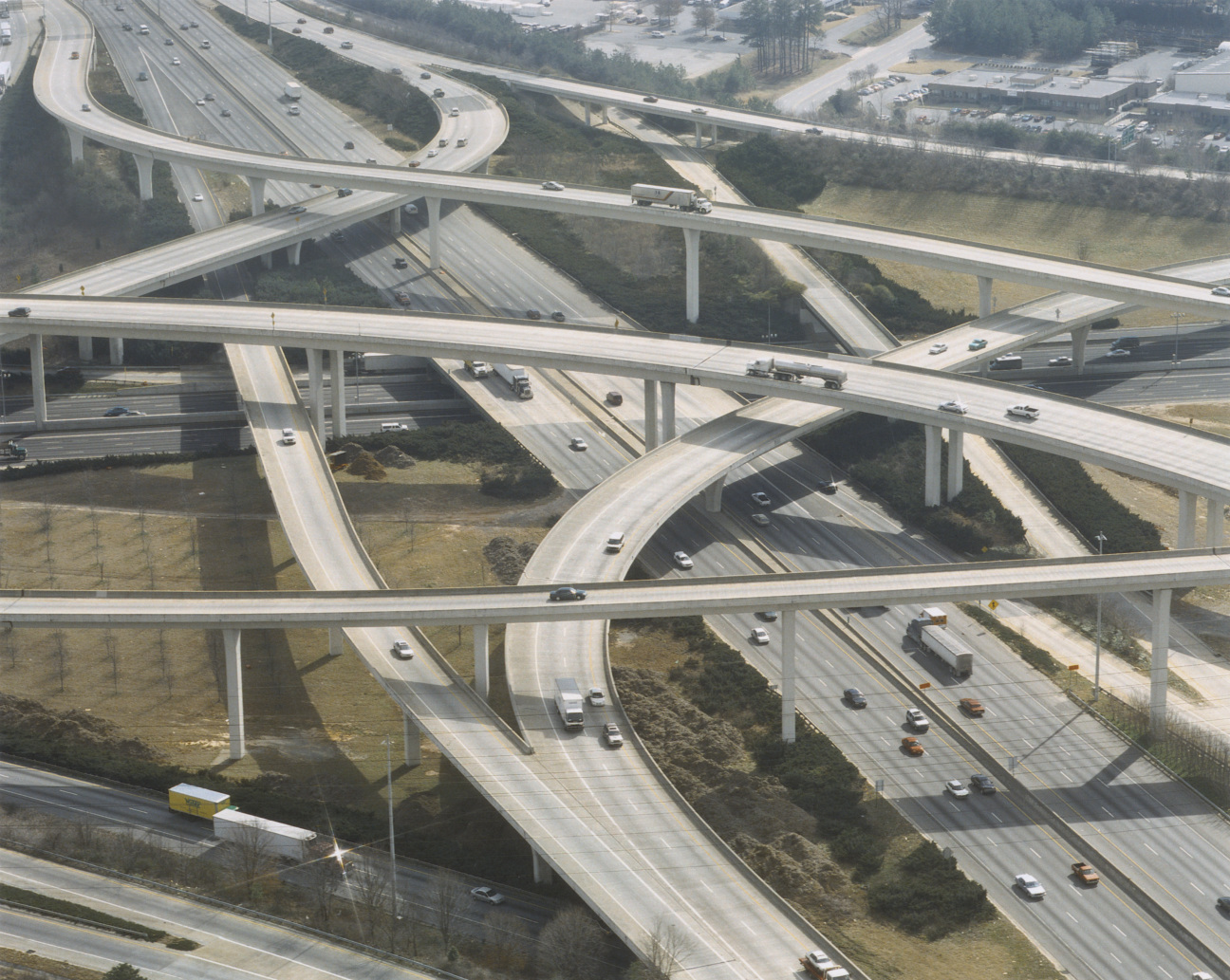

RE: I love the South for its unhealthy food options and for the crazy contradictions and college football, etc. One could say that the South I depict is specifically generic and yet totally personal. The highway overpass—a marvel of tangled off ramps and flyovers known in Atlanta as Spaghetti Junction—is the same one that I had to navigate my first time driving to Karen Light’s house at 15 in a red Buick Skylark station wagon.

JS: While we’re still in your adolescence, can you tell me about your earliest relationship with photography?

RE: My dad was an avid amateur photographer in the early ‘70s. In fact, he won an award—a second place ribbon if I remember correctly—at the Southern Bell Telephone company’s photography exhibit at the Breakers in Palm Beach. The image he made was a long exposure of fireworks, and he put it in a rustic looking wood frame. I have found boxes of slides that are all lens tests with me holding up a card that says 5.6 @ 1/30, 8.0 @ 1/30…etc. I have no memory of it, but it clearly happened. I’m sure that this pre-hippocampal exposure to photography, and the (subconscious?) desire to “follow in the footsteps” of my father made it more likely that I’d choose the camera over another medium.

JS: Whoa, I forgot about your dad’s history in photography…and, I mean, dude I’ve got a picture of yours that’s a long exposure of lightning in a wood frame! So why do you take pictures? Or is it: why do you take pictures?

RE: Oh shit. That’s true! Re: lightning⚡️Why do I take pictures? Just before I discovered the 4×5, I thought film/video (or TV) was the best—“truest”—medium when I was in art school. And then my mentor/teacher for film and video left the school for a job at HBO. The next semester I started shooting with 4×5 and it was more technical and slow than walking around with a 35mm camera. I think that suddenly cracked open the New Objectivity photo history. I consumed it all very quickly. Suddenly I was a knowledgeable and competent artist, which—because people are this way—led me to decide painting was the best medium. As I got into painting in my last year at ACA [Atlanta College of Art] I realized it was just gonna take too long to be great at it. And I thought I was already good at photo 😂. Plus, seeing the Bechers [Bernd and Hilla], [Thomas] Ruff, [Andreas] Gursky, and Jeff Wall making what I considered the most vital artworks of that moment, I decided to stick with photography.

JS: This is all interesting for sure…But I think what I really meant is why are you an artist?

RE: I wanna say I didn’t have a choice…or the choice was a grim script of either nine-to-five, Dockers, Oakleys, and Olive Garden, or be an artist, move to NYC, and let the chips fall where they may.

JS: How do you think about time these days? What was it like to put together this book?

RE: I think quarantine reshaped my notion of time and photography. While putting the book together, I often found my way back to something forgotten or accidentally placed in the wrong box, which would lead to another forgotten tangent. I started the folder “American Polychronic” on April 4th, 2020. I had agreed to do the book with [publisher Michael Mack] pre-pandemic, but I didn’t have a title until then. I’m sure it would have been a different book without the quarantine.

JS: So I’ve taken several portraits of you over the last 20-something years—on the side of a highway, wrangling a pigeon—marking different phases of your life and practice. What do you see of yourself in these, and how do they relate to the guy I just shot in Rockaway?

RE: It is freaky to recall that I was driving my grandma’s ‘66 Chevelle [portrait of Ethridge from 1998]. And that red quilted jacket. I look skinny. And tired. Lol. I can relate to the tired part now tho for different reasons. Back then it was from staying up late, now it's from…being 53? When I think about the work I was making then and now it seems like a logical thread to get from there to here. But if you told me what I would be doing or that we would be having this conversation, I wouldn’t have believed you!

American Polychronic is now available via Mack Books, and its two concurrent shows are on view through February 18, 2023 at Andrew Kreps Gallery and February 25, 2023 at Gagosian Gallery 976 Madison in New York.

in your life?

in your life?