As the Executive Director of Print Center New York and a former MoMA curator, one might assume that Judy Hecker’s home art collection would be an enviable mix of rising artists and rare finds—well, it is. Her New York abode is filled with works by the likes of Pat Steir, Glendalys Medina, William Kentridge, and more. Working at the Print Center does give her a “home field advantage,” as the collector puts it, but her eclectic array is also the result of years of accumulation and interest, kicked off by her parents, who took a modest budget and put it toward hanging pieces that Hecker confesses “confounded our suburban neighbors.” Here, the art-world insider shares how she continued in their risktaking legacy.

CULTURED: What draws you to printmaking in particular?

Judy Hecker: I was always interested in the intimacy of prints: their smaller scale, their intricate linework and particular marks, and the way they make you look really, really closely at an image. They draw you in. On the other hand, you can be enveloped differently by a 10-foot print that is anything but intimate. There’s a diversity of form and practice in printmaking, which keeps you on your toes.

So there is no one particular thing, but there is a set of principles that prints “live by” in a way no other medium can, like their vast and complex range of techniques for creating, the fact that they’re more affordable since they’re available in editions, and the whole ecosystem of the field, which includes the collaborative space of the print workshop and the expertises of the printer and publisher involved. It’s a field that is about access and inquiry and is full of creative, specialized, and extra nice people.

CULTURED: What do you think makes the New York art scene distinct?

Hecker: I think the sheer concentration of artists, galleries, and print workshops sets New York apart. There are urban centers across the U.S., to be sure, and sometimes you can get to know a local art scene far better in a smaller city or a less concentrated region, but the punch and dynamism of New York is unparalleled. Every night there is something to see or do, and for free. You have multiple clusters of galleries and openings to explore, not only in Chelsea, where Print Center New York is located, but also in Tribeca, the Lower East Side, and the Upper East Side. The range of museums and nonprofit spaces—from big to small—is also unending, and they all offer outstanding programming.

CULTURED: How would you characterize your collection?

Hecker: Eclectic and a work in progress—my husband Matt and I didn’t set out with any grand plan, except to find works by artists who are really achieving something in printmaking that they can’t in another medium. We’re also totally out of wall space, so we are buying smaller single editions rather than larger works or portfolios and series, for instance.

Our tastes and interests have also changed over the years; we are now more excited by discovering artists who are new to us, like Glendalys Medina, a Bronx-based artist who printed with Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. Medina’s works combine abstraction, something we’re drawn to, with forms originating from hip hop and references to the history of Puerto Rico, and this particular print uses gold ink on pink paper and flocking. It’s super textured and layered, there’s a lot to absorb.

Earlier, we collected prints by “established” artists who have had extensive printmaking practices, like Vija Celmins, William Kentridge, Richard Tuttle, and Julie Mehretu, waiting patiently until we could find the right work at the right price. These are artists for whom printmaking has played, and continues to play, a central role in their practice —and they’re really, really good at it—but since their work is well known, there’s less of an element of discovery. It’s more about the chase.

CULTURED: What is the first piece you ever bought?

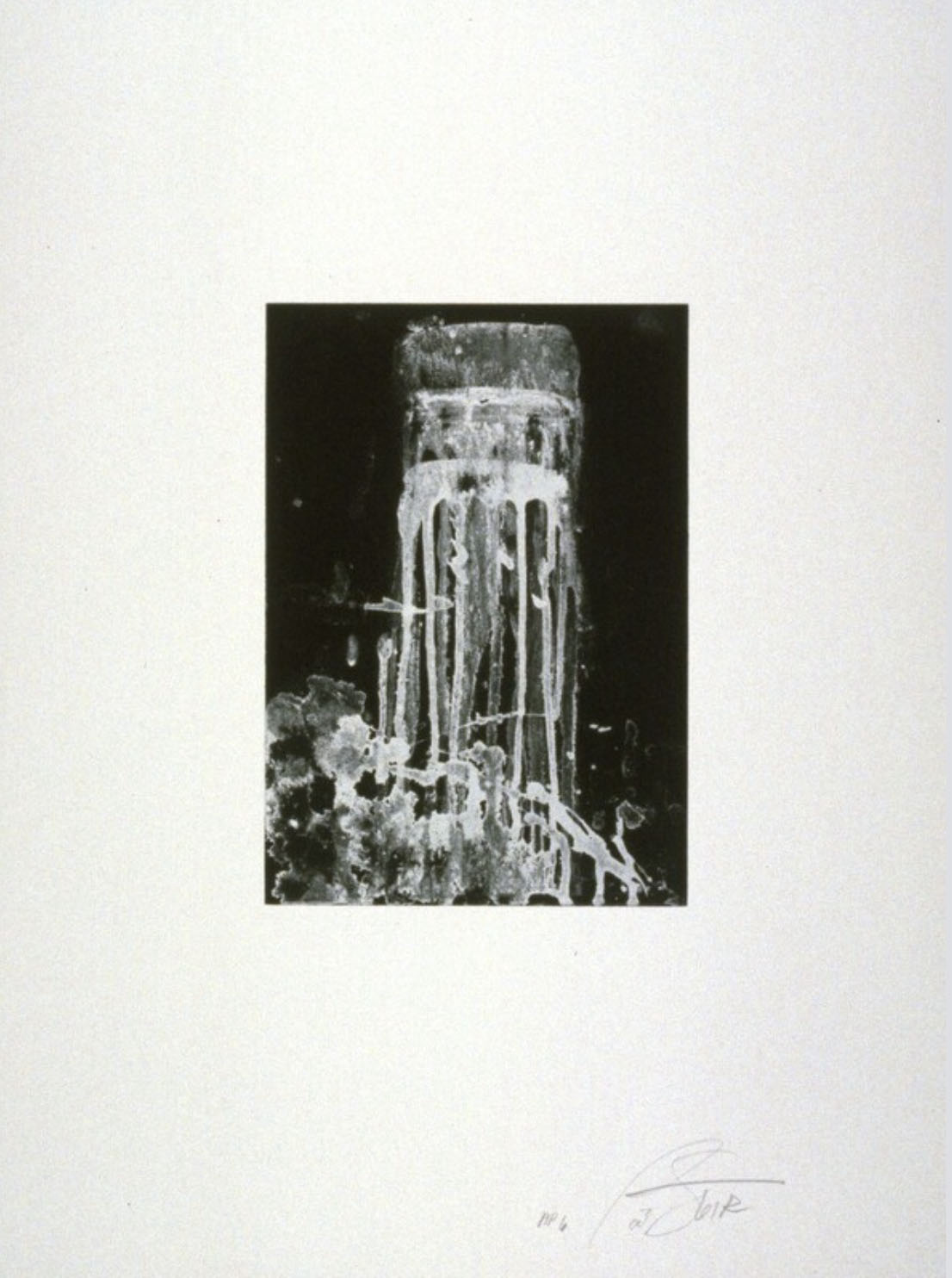

Hecker: The first piece I ever bought was a little Pat Steir waterfall print—maybe her smallest print ever. However, to me, it was anything but lilliputian. It was the early 1990s and I was working at a gallery on 57th Street (back when 57th Street was a hub) right out of college, answering phones and the like, and the salary was surprisingly decent. I was blown away by the monumental nature of Pat Steir’s wall-sized paintings hanging in the racks and back rooms for clients to view; their poured and splattered gestures were abstract but systematic—on a scale I had never seen—and this mesmerized me. She was a post-Pollock woman artist with an aggressive vision and process.

I barely lasted a year at the gallery but learned, valuably, that while the gallery itself didn’t deal in prints, many of their artists created prints, and they were affordable. I visited Crown Point Press, the renowned yet welcoming San Francisco publisher and print workshop, while on a personal trip, and made my first purchase: Small Vertical Falls, 1991. Its image is less than a foot tall, but billowing and splashing with power. I remember the excitement of owning my first work of art like it was yesterday. When I mentioned the purchase to Pat the next time I saw her at the gallery, she was quite moved and that moved me. And my interaction with Crown Point Press was invigorating; I gained the knowledge that prints involve interacting with interesting people, have their own specialized spaces for making, are a pathway to collecting and fit in a small NYC apartment.

CULTURED: Which work or works provokes the most conversation from visitors?

Hecker: Last year I bought a 2018 multiple by Rirkrit Tiravanija at the Printed Matter NY Art Book Fair. It is a tray, like a cafeteria lunch tray, screen printed with the text: FEAR EATS THE SOUL. It’s propped up in my kitchen. If you know Rirkrit’s work it makes perfect sense. Others have asked, “What’s that?” and I explain that he’s an artist whose work involves shared community activity like cooking and eating, and his objects relate to these activities or utilize provocative phrases.

That the tray is a pun on “eats," for me, is great. The statement has become a daily affirmation (just stated in the negative); I can’t avoid it each morning as I have coffee. As it turns out, this Fall, MoMA PS1 is opening the first U.S. survey and largest show ever dedicated to Rirkrit’s work, so with that hopefully more people will learn about his messages and playfulness. Print Center New York in fact published a new benefit print with Rirkrit late last year. It's a stunning play on his interest in newspapers, current events, everyday objects, and Marcel Duchamp. It’s a fundraiser for our programs, and it has gotten very popular since his exhibition was announced. It’s also the first work of his to ever include a self-portrait!

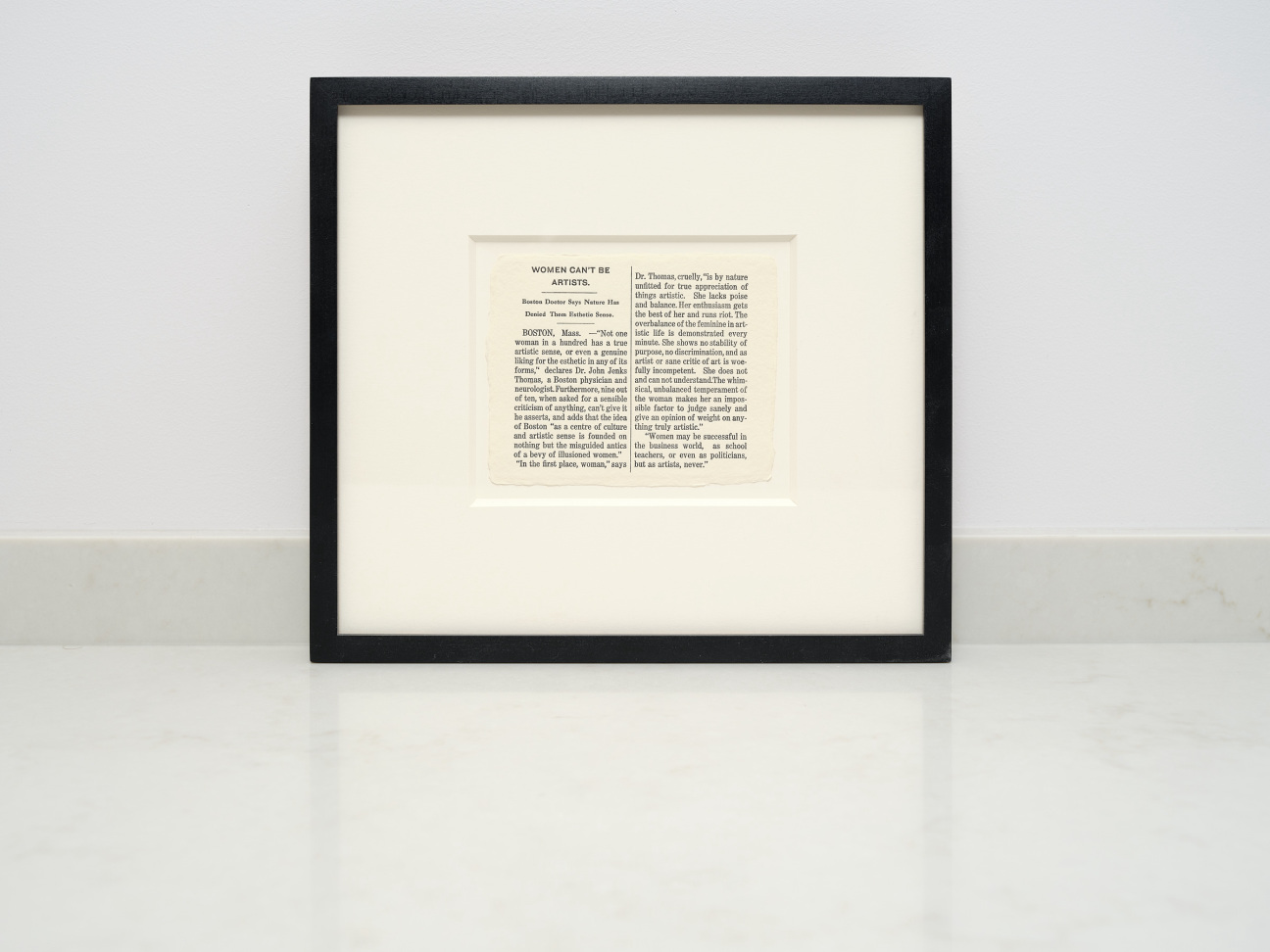

Another piece that provokes conversation is a tiny print by Ruth Lingen, an artist and print publisher who lives and works in New York. It looks like an actual news article, but it’s exquisitely printed in letterpress from handset type on handmade paper. And it’s framed. So that’s your first and second clue that this isn’t just any newspaper clip. Titled “Women Can’t Be Artists," it appropriates a 1910 article from The New York Times, which outlines all the reasons women are not fit to be artists. It’s something between a Robert Gober and a Jenny Holzer, and exquisitely produced as only Ruth can do. But upon seeing it, people are perplexed, drawn in, and then a conversation always ensues.

CULTURED: Which artist are you currently most excited about and why?

Hecker: I’m excited about the artists that we are showing presently in our "New Voices" summer exhibition. It’s a daring show that brings together eight artists—four from New York and four from across the U.S.—whose works use printmaking in wildly different ways. You’ll see installation, sculpture, collage and fabric, and each incorporates printmaking in a novel way. But I was especially struck by Nina Jordan’s traditional woodcuts, which are masterfully carved and printed in soft pastel and muted colors—you also see the wood grain of the block in the prints. These scenes are devastatingly beautiful and devastating, period. They portray homes submerged in water, with a tension between the beauty of Nina’s hand and the water (a life-giving force), and the havoc that global warming has had on our planet, homes, and lives, with no end in sight.

CULTURED: What was the most challenging piece in your personal collection to acquire?

Hecker: We had long wanted to buy a print or series of prints by Julie Mehretu, but they either sold out quickly or were too expensive to consider. We occasionally peruse the auctions to see what is being offered—bargains are possible at auction—and years ago we saw an early set of etchings Mehretu created with Greg Burnet at Burnet Editions, and decided to go for it. We examined them during the auction preview (condition can be an issue at auction), but these were fine and even the frames were usable. Surprisingly, there was not much bidding activity—these were early prints, and small, so perhaps a little under the radar—so we were successful in acquiring them. "Landscape Allegories," 2004, a series of seven etchings printed in differently tinted black inks, tell an extended story about Mehretu’s exploration of form, technique, history, and civilization.

CULTURED: Is there one piece that got away, or that you still think about?

Hecker: The great thing about prints is that they are typically editioned, so usually there’s more than one out there and you don’t have that pressure of a unique painting or drawing disappearing into a collection, never to be seen again. Prints linger, prints turn up again, there’s always another chance. I think that’s part of why the field is less competitive than others. It’s a democratic medium; there’s just more available for more people.

Even so, yes, they can get away. You hesitate, you’re busy, you have other priorities. Prints also can get more expensive over time. As an edition sells out, the remaining prints may be priced higher, or when a print reappears on the secondary market it may sell for more. One print that I think about often and wished I owned—but have been fortunate to see a lot nonetheless—is Nicole Eisenman’s Beer Garden, 2012-17. It’s the artist’s largest (over 4 feet wide) and most laborious detailed etching that was years in the making and is full of so much humanity and humor. It’s a small edition of 15 so they sold relatively quickly—mostly to museums and a few lucky collectors. Before you knew it, it was gone.

But because I have worked in the field for so long, first at museums and now at Print Center New York, I have been spoiled by the access that I have to prints professionally, day in and day out, so I never really "miss out." They’re part of my life in perhaps a more important, deeper way. For instance, this past winter we opened Eisenman’s first exhibition in New York to focus on her printmaking in more than 10 years. We installed Beer Garden front and center on a wall, and it was gratifying to walk in every day and see it myself, but moreover to see how many people (over 14,000!) got to see that print during the show.

in your life?

in your life?