Justine Triet took home this year’s Palme d’Or, the highly desired top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, where a third of the in-competition filmmakers were women. A third may not seem like a lot, but compared to five years ago (three female filmmakers in competition) or even ten years ago (one lone woman in competition), Cannes has made significant strides toward gender parity. So too have other film festivals, including Sundance––the Park City indie extravaganza boasted that over half of the featured directors in its 2023 edition were women or non-binary. Even more impressive is New York’s Tribeca Festival, where women make up a purported 68 percent of the filmmakers this year. Tribeca hasn’t been shy about touting this statistic, but what is the landscape like for the female filmmakers of this year’s festival?

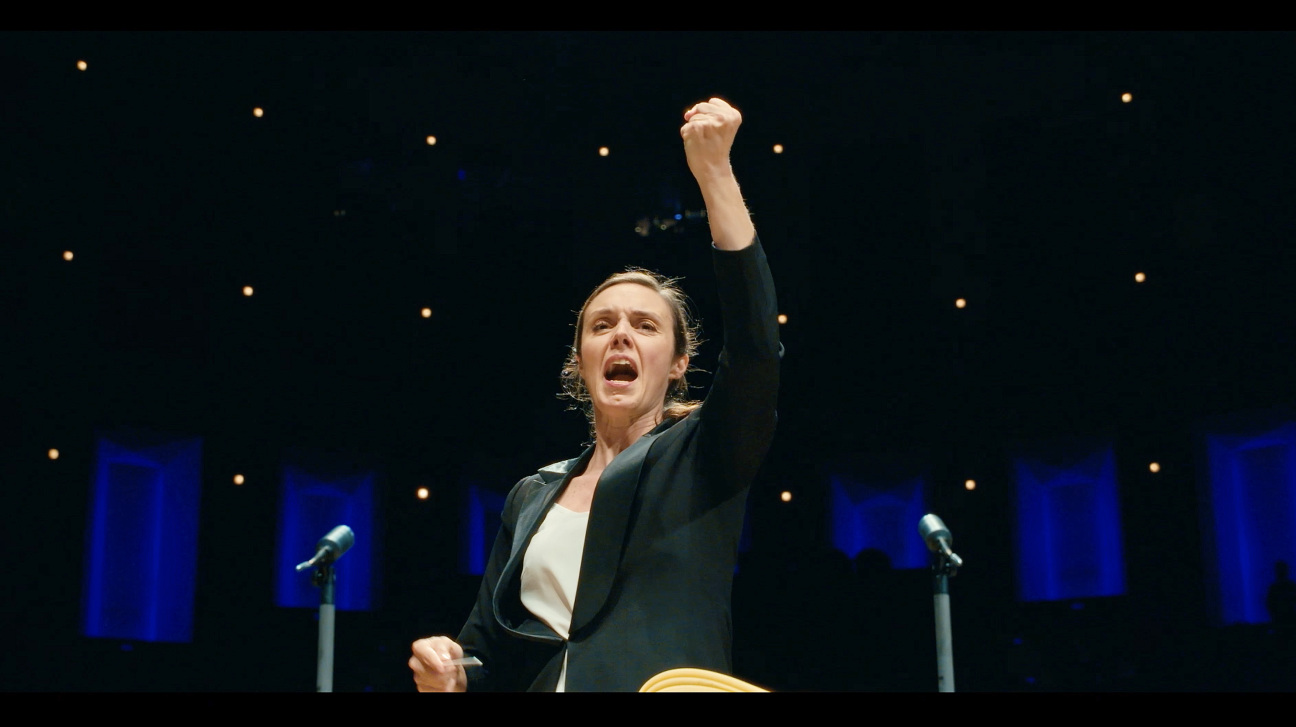

Several of the female and/or non-binary directed movies at this year’s Tribeca Festival are promising debuts by exciting new filmmakers. Maggie Contreras’s documentary, Maestra, picks up where the discourse from Tár left off: it’s an in-depth look at the La Maestra female conducting competition in Paris. Maestra hones in on a diverse set of women––from Greek maestro Zoe Zeniodi, who juggles freelance conducting with motherhood, to Mélisse Brunet, who confronts a past trauma returning to Paris, to Ustina Dubitsky, who mourns her native Ukraine.

Contreras’s interest in the variety of women’s experiences extends beyond what’s in front of the camera; her film includes a disclaimer in the credits to specify that 80 percent of the crew was female. Contreras was able to deliberately craft a film that celebrates female artists on- and off-screen, addressing much of what Maestra boils down to: that while championing women in a specific artform is valuable, the greater opportunity is to provide these women a chance to work together, evidenced in the film’s conclusion when La Maestra’s competitors sit down for a raucous, joyful dinner all together.

Monica Sorelle’s Mountains, a stirring, beautifully rendered portrait of a family of three living in Miami’s Little Haiti, was also a highlight. The film is about the gentrification of an ever-developing neighborhood, but as Sorelle and co-writer Robert Colom discussed in their post-screening Q&A, the film’s focus is really on “Black joy, and immigrant joy.” Eighty percent of Sorelle’s film is in Creole, with many of the translations in the script done by her mother––a labor of love in the most literal sense. That Sorelle and Colom have been granted the opportunity to bring their world to New York is its own kind of victory, removed from constraints of diversity metrics.

But Tribeca championing so many female filmmakers this year feels a bit like a catch-22. It is an undeniable good to have more women behind the camera at film festivals; in years past, festivals feigned difficulty of including more than a quarter of women-directed films in their line-ups. Though festival selection has never guaranteed commercial, let alone independent, success, the rise of streaming services, and the lack of financial security that has accompanied the shift (the cause, in part, of the current WGA strike and possible future SAG strike), makes the future of festival representation all the murkier. A filmmaker applies, their movie is selected, the film screens at the festival, but the future of a smaller film remains unclear. Maybe they get distribution with a streaming service, but that doesn’t guarantee good placement on a series of endless lists. Without an active buyers’ market or a shiny PR team, it’s possible their movie never gets distribution.

“The festival only cares about you if you have celebs in tow,” one anonymous rep told me at Tribeca. It doesn’t help, in this case, to read up on the festival’s diversity achievements when Chelsea Peretti’s aptly titled First Time Female Director dominates any search into how diverse Tribeca’s line-up really is.

That doesn’t even get into the amount of money that goes into Tribeca itself. The festival’s lead sponsor this year is OKX, a cryptocurrency exchange that isn’t available to crypto-spending (or trading) U.S. citizens. For all the writing on how crypto markets might create a more equitable economy, the people profiting are predominantly male. Tribeca’s OKX sponsorship does not redistribute wealth in any meaningful sense; rather, it takes Tribeca’s gender parity and uses it as a shield. Before one of the screenings, there was an ad that suggested women were capable of anything they wanted to do. This is, of course, true, but not the first thought that comes to mind when thinking about Stacy’s Pita Chips. The future might be female, but it is also bleak.

What a balm, then, that these films have a strong enough sense of self to push past the noise of the festival’s PR machine. Sorelle pushed back at the Q&A about the “weight” of representation. “It [doesn’t] feel heavy because this is what we know,” she explained. “We thought of Mountains as an archive,” added Colom. Consider Tribeca Festival as more of an archive than a celebration, more of a museum than a shopping center. From Georden West’s “queer bricolage,” Playland, a unique celebration of a now-shuttered Boston gay bar, to Virginie Verrier’s ruthless and thrilling soccer epic, Marinette, there are films here that expand and unpack womanhood, queerness, or community, but break through form and narrative altogether, creating ever-daring, ever-original movies. Tribeca can use them for its own benefit––to acquire bigger and better sponsors––but they will always fall short of the art they showcase, and the filmmakers they claim to champion.

in your life?

in your life?