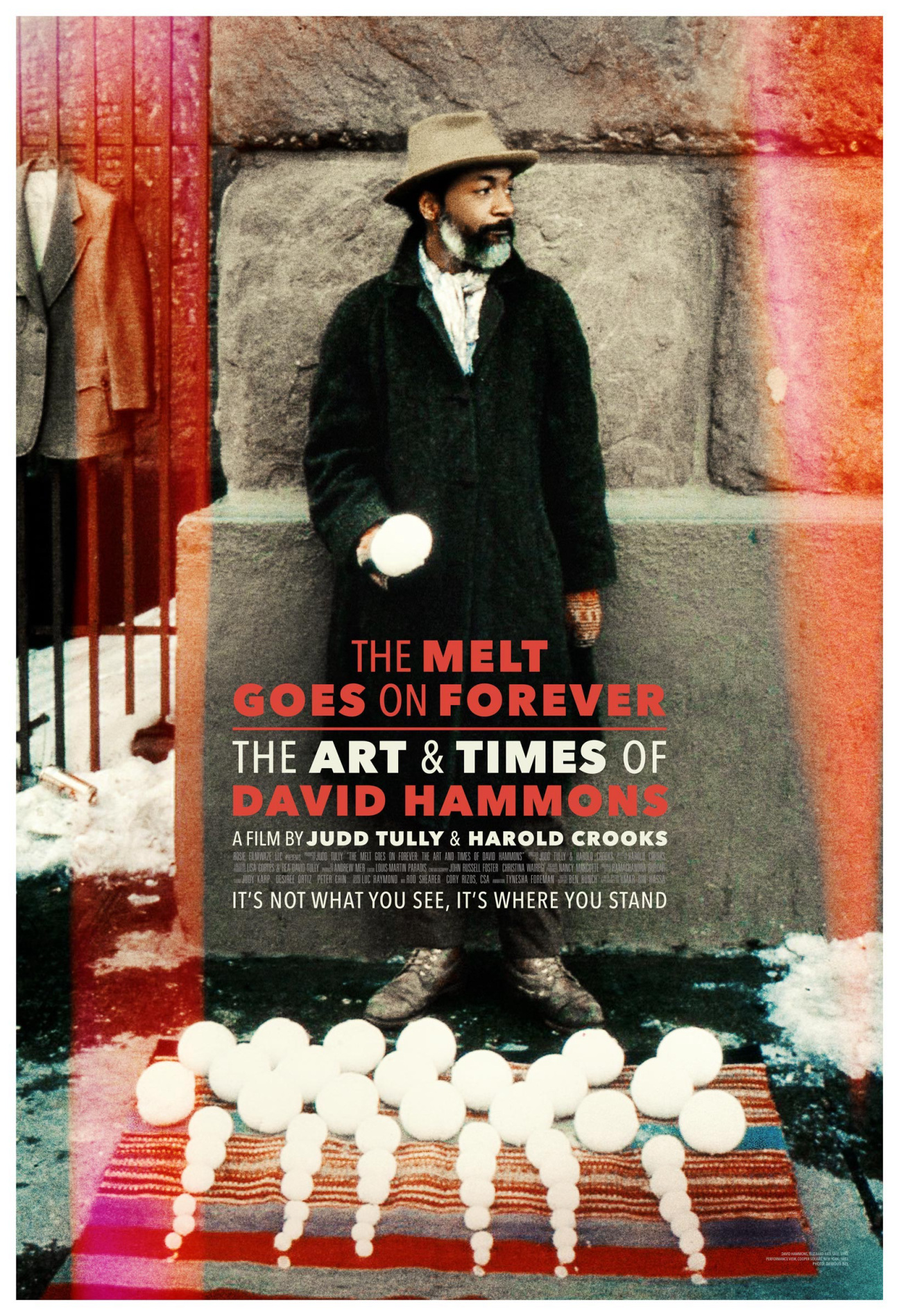

David Hammons will turn 80 next month. In the 60 years that he has practiced as a sculptor, performer, filmmaker, and writer, one would be hard-pressed to find a maker as simultaneously elusive and beloved as the Springfield, Illinois-born artist. He playfully embodies the often contradictory demands projected onto living artists, acts as a mirror to the art world’s money-obsessed follies, and has found the key to sustaining relevance through grit, not gimmicks. His evasive strategies and insurmountable impact on art-making make him a challenging subject, so, when Judd Tully and Harold Crooks chose to dedicate a documentary film to Hammons, they focused their lens on his practice more than his persona.

Through archival footage, animation, an entrancing jazz score, and in-depth interviews with art world personalities like Lorna Simpson, Robert Storr, Henry Taylor, Betye Saar, and Franklin Sirmans, the directors offer a glimpse at the traces Hammons will leave in art history books, and those that cannot be contained in words. The Melt Goes on Forever: The Art & Times of David Hammons landed in U.S. theaters last month, but this week it will make its mark on audiences in two of the art world’s mini-capitals, Basel and Marfa, with screenings at Stadt Kino and CineMarfa on Friday and Saturday respectively. To mark this occasion, CULTURED called up Tully and Crooks to talk about the film’s genesis, intentions, and reception so far.

CULTURED: How are you feeling since the film’s release in May?

Harold Crooks: We feel that the film is worthy of the subject, and that we have managed to navigate what could obviously seem to be a potentially fraught journey in a way that has been endorsed by important art world people, people in David’s world, and audiences, so it’s incredibly gratifying.

Judd Tully: This was a project that began in 2013 and we were collaborating for the first time. It was very slow getting off the ground, to put it mildly, and further down the line Covid came, and that's when we were really in the thick of things. Given the obstacles and delays, it’s very satisfying.

CULTURED: Let’s talk about the genesis of the documentary. Why David Hammons? Why you two? Why now?

Crooks: I arrived in New York from Canada in 1990, and Judd was part of a circle of art world friends from my wife, Medrie MacPhee, who is an artist. So I immediately inherited Judd as a friend all those years ago. Over the years, we talked about the possibility of a collaboration. Finally, around 2013, we decided in earnest that we would look for a subject and, given that I come from the documentary filmmaking world and Judd comes from art writing and art journalism, it was obvious that it would be an art world project.

I was very struck early on when we were searching for a project and Judd was talking to me about the mystery of [David’s] posture towards the art world. Someone has used the term “tactical evasion” for David. Glenn Ligon, in an essay he wrote on him, talked about three things that struck me: that David’s work could be considered a deep critique of American society, a deep critique of the elite art world, and also utopian.

CULTURED: What did the conversations look like between you two on what form this film would take?

Crooks: We agreed right from the get-go that this was not going to be a biopic. This was going to be an investigation of the influences on David. This was going to be a film about the deeper significance of his work, and in order to do that, it was simply a matter of reaching out to art historians, curators, and gallerists, who had something of significance to say.

Tully: We already knew that there was no point really in approaching David to say, “We want to make a film about you.” We were very careful from the very beginning, first by contacting one of his longest and most loyal champions, an art collector and MoMA trustee, A.C. Hudgins, about what we were planning to do. We wrote a letter to David through A.C., and A.C. responded in a kind of one-line email to the effect of “Well, I don’t think David is going to participate, but you never know.”

[Gallerist] Jeanne Greenberg-Rohatyn talked to us about how she would go up to Harlem where [David] lived, and she would leave flowers by his door with a note. She did this three times, and on the third time, the door opened one floor above her, and someone said “You got the wrong door.” It was David Hammons, and that’s how they met. She had that kind of maniacal focus and persistence, which was very telling to me.

CULTURED: Do you feel like you know David Hammons?

Crooks: In the same way that David has talked about not being interested in knowing his jazz heroes but [is interested] in their music, for me the question was never really knowing him. The goal of the film was to decode the meaning and significance of his practice. In the film, when he himself comes to the realization that what matters to him is the daring of the process rather than the process itself, that’s almost all I need to know psychologically about David.

Tully: Even the subtitle, “The Art & Times of David Hammons,” was very important to us because it wasn’t just about David Hammons. It was about the Otis Art Institute, Charles White, Betye Saar, and the whole journey from LA to New York to Europe and the rest of the world…

CULTURED: Hammons created a new artistic language. How did you two think about dialoguing with his practice in the film’s visual language?

Crooks: One of the ways in which we were determined to raise the aesthetic level of the film was through the use of excerpts from a rap poem that Steve Cannon had written for the catalog of an exhibition David had at MoMA PS1 around the time of the first Gulf War. We found footage from a Chantal Akerman documentary, News from Home, 1977. And then the question was how are we going to get the poem into the film? Steve was blind by this point, so we experimented with several readers, and then our composer, Ramachandra Borcar, became completely obsessed with David’s use of found objects.

It just so happened that Ram had worked on a previous documentary that had used music from The Last Poets, a famous political rap group considered to be the forefathers of hip hop. Ram said, “Why don’t we try to get one of The Last Poets to read Steve’s poem?” Lo and behold, we located Umar Bin Hassan, who very happily agreed to do it. Then there was a question of wanting to use animation for materials that weren’t available. I found Tynesha Foreman, who had done a number of animations for The Atlantic on very political subjects. This was another way that the experience of the film was elevated.

CULTURED: The art market is a major presence in the film. The film gives a quite nuanced view of what it means for a marginalized artist’s practice to be monetized and “contained” in that realm. How did you navigate that dialogue, specifically as two older white men?

Tully: We had to somehow deal with this artist who was famously elusive, whose most famous works were only visible to people who passed by it at that moment or captured it in a photograph, and yet these pieces would come on the marketplace at auction. We were interviewing Jeanne Greenberg-Rohatyn, and I made a comment about how one piece went for this record $8 million. She said that it was so undervalued, saying that we had no idea of the true value of Hammons’s work.

Crooks: There’s another dimension that is very important for me. One of the most illuminating comments that David makes in the film is when Papo Colo, the co-founder of Exit Art says, “David, we should never ever be in the mainstream.” David’s immediate reaction was, “Well, the important thing is to be radical in the mainstream.” It says so much about David’s practice.

He has managed to be both the ultimate outsider and the ultimate insider. I mentioned the fact that we were working on the film to the head of the painting department at Cooper Union, and he said, “There is no artist that my students admire more than David Hammons.”

in your life?

in your life?