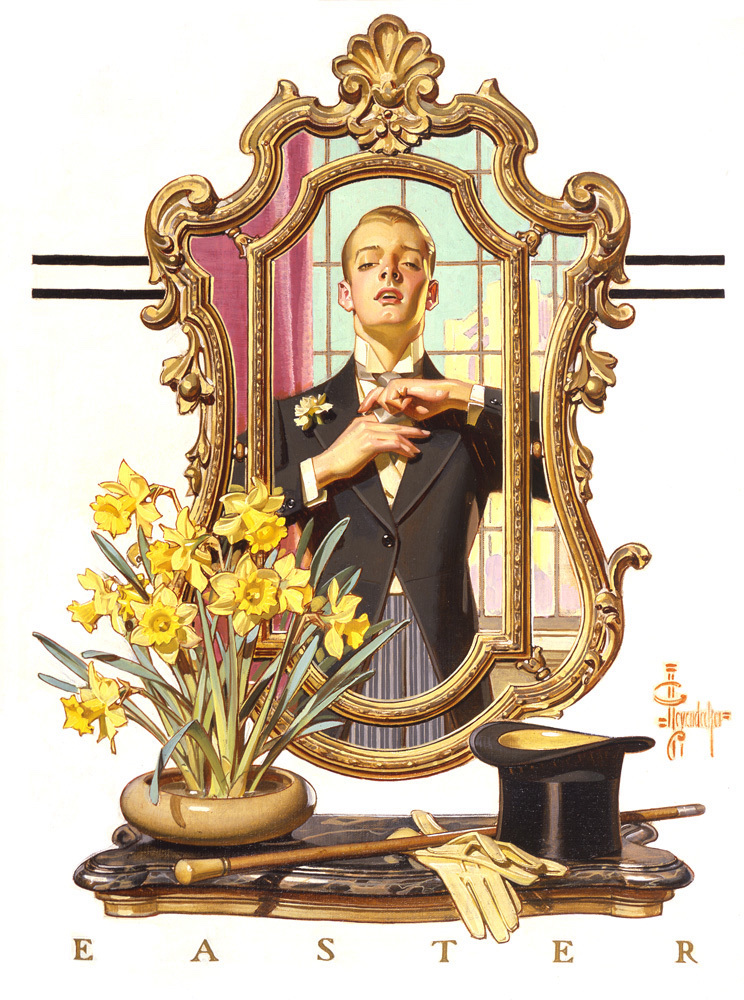

Even if you haven’t heard of J.C. Leyendecker, you’ve likely seen his work. The commercial artist did much to shape American visual culture in the first three decades of the 20th century. You have Leyendecker to thank for such cultural mainstays as the playful, chubby Santa Claus icon, the delivery of flowers on Mother’s Day, and the sash-wearing baby that symbolizes the arrival of the New Year.

But perhaps more than anything else, Leyendecker’s enduring influence lives on in the Arrow Collar Man, an aspirational symbol of American cosmopolitan masculinity that originated in advertisements for shirts and detachable shirt collars. What few people knew at the time was that the model for the Arrow Collar Man—one of America’s most influential male icons—was Leyendecker’s lover of 50 years.

The wide-ranging impact of Leyendecker and the queer-coded imagery in his work are the subjects of “Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity,” an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. The show presents 19 of the artist’s original oil paintings as well as a range of magazine covers and commercial illustrations that appeared in the pages of popular publications, on roadside billboards, in store windows, and on mass transit.

“J.C. Leyendecker was a talented artist whose illustrations have come to embody the look and feel of the first half of the 20th century,” says Donald Albrecht, the exhibition's guest curator. “Not only did his work exemplify the zeitgeist, but it depicts a deeply nuanced view of sexuality and advertising that broadens our understanding of American popular culture.”

Born in Germany in 1874, Leyendecker immigrated to Chicago with his family as a young child. He studied at the Chicago Art Institute and at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he became enchanted with popular advertising posters by artists such as Alphonse Mucha and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Upon moving to New York in 1900, Leyendecker secured the menswear commissions that would make his name. When Cluett Peabody & Company, a prominent shirt manufacturer, hired him to advertise their Arrow Collar shirts, Leyendecker developed the legendary “Arrow Collar Man.” The figure became so linked to a particular kind of man—dapper, cosmopolitan, capable—that the term found its way into a Cole Porter song (“You’re the top / You’re an Arrow collar”) and even inspired the Broadway play Helen of Troy, New York.

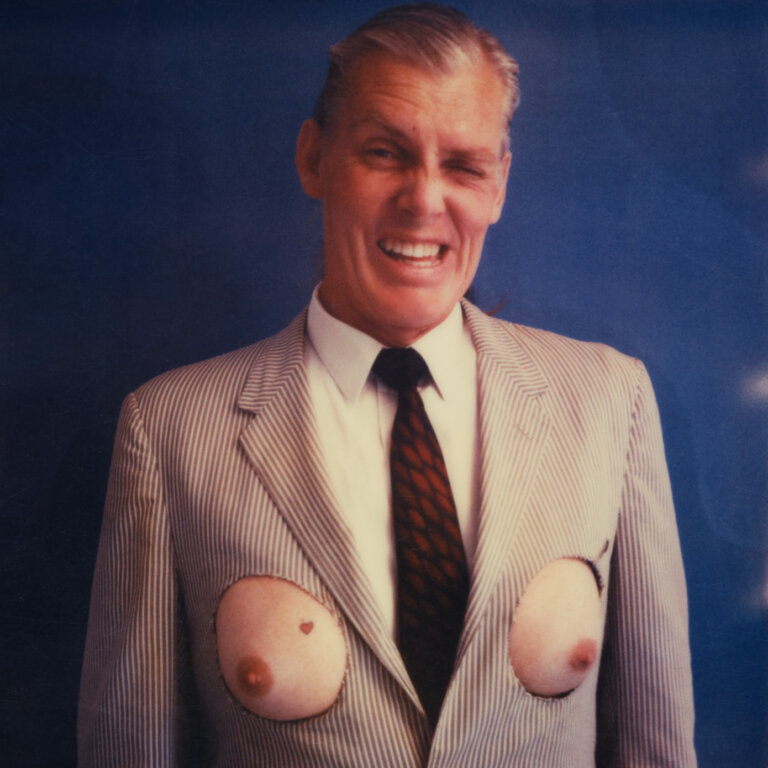

Throughout his career, Leyendecker developed various images of masculinity for the mass market, from muscular American sports champions and soldiers to stylish, lithe men posing for the fashion industry. No matter the context, the men were often pictured admiring one another or themselves as they handled suggestive props (oars, golf clubs, missiles, canes, megaphones). The model for most of his drawings was his lover and business manager Charles Beach.

“As a gay man, [Leyendecker] was especially adept at depictions of the male body and of male behavior and interactions,” says Albrecht. “His illustrations often exhibited a range of masculine types—the soldier, the sailor, the athlete, and the aesthete—but almost always white men.”

Subcultures that challenged sexual and gender norms became increasingly present in cities like New York during the 19th century. While Leyendecker almost exclusively depicted white men, the exhibition juxtaposes his work with documentation of his nonwhite queer and gender-fluid contemporaries, such as Langston Hughes and Gladys Bentley.

As the modern gay rights movement marks its 54th anniversary this month, what should we make of the fact that one of the most formative images of 20th century masculinity was a depiction of a gay model by a gay illustrator? First, that gay people have always been here. And second, sex sells.

“Under Cover: J.C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity” is on view at the New-York Historical Society through August 13, 2023.

in your life?

in your life?