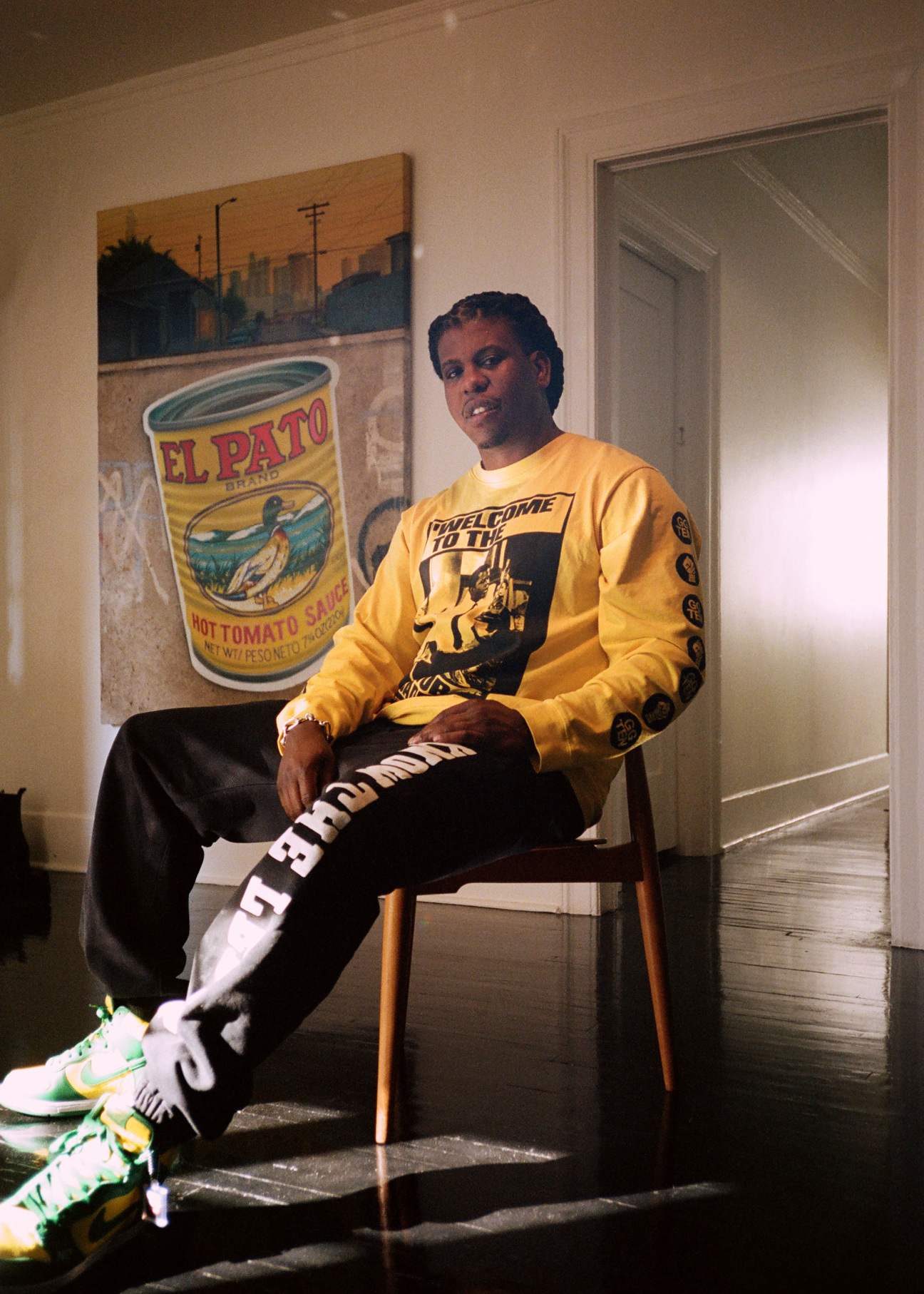

Jon Gray

Jon Gray started buying art years before he realized where he had developed the proclivity. He had soaked it up at home, during weekend dawdles through the halls of the Studio Museum with his mother when they were all living together in Spanish Harlem. He describes his grandmother’s house papered with posters and other visual representations of Black life: “The things my grandmother collected were things she found on 125th street and put on the wall. It was just to have the ambiance, you know? To have a home surrounded by Blackness. I grew up in a revolutionary environment,” Gray says. “Art came to me.”

And art won’t leave him alone. When I first heard of Gray, it was as a founder of Ghetto Gastro, an industry-disrupting food collective from the Bronx that had every gallery and art institution clamoring for a dinner. Now, Gray is an artist in residence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Jon Gray of Ghetto Gastro Selects,” an exhibition he curated from Cooper Hewitt’s permanent collection, just closed in February. Gray is completely enmeshed—and yet it is still the first memories of his grandmother that drive his own collecting habits, as well as the friendships he made along the way, like with curator Larry OsseiMensah, who encouraged Gray early on to do studio visits. Or his friend Todd Merrill, who encouraged him to attend his first Art Basel Miami Beach in 2008, where he saw “30 Americans,” a life-changing show of the Rubell family collection featuring icons like Rashid Johnson, Renée Green and William Pope.L. “Seeing all of this art on the walls and the representation of Blackness, I was very inspired but also a little sad. Besides the Studio Museum, we often don’t get to see this type of representation within our homes,” Gray recalls. “That had me thinking like, ‘What can I do to be a part of the conversation?’”

He jumped in hands first, the same way he did with Ghetto Gastro, by lending both money and time to practices that resonated with him. “Community is immunity,” Gray says. “People of color create a lot of value, and oftentimes the value is taken into different communities. I wanted to really support artists of color. For me, it’s not just about the object or painting or sculpture, which is probably why I’m interested in living artists.” Not just living artists, but artists who give back, like Mark Bradford and Lauren Halsey.

The emphasis on what we can do in this life for each other comes up again and again. Gray is one of those individuals that can harmonize the micro and the macro. He’s not a flipper or a speculator, but instead, someone who finds the process just as important as the result, if not more so. This is why the term collector, with its colonial roots, doesn’t quite sit right with him. “Artworks have a piece of the artist in them and I’d never want to walk away with that. I like to be that additive sauce to whatever is going on,” he says. “What can the things I buy do when I’m gone? How can I serve? Is there a cohesive story that everything fits into? I think about [the art I own] as chapters or pages in a book.”

Rocky Xu

During Rocky Xu's decade at Nike corporate, the globetrotting consultant spent his fun money on collectible streetwear. It turns out sneakerhead culture is a gateway drug to art. Once the thrill of the drop ran dry, the only way to get up again was to investigate those voices the fashion designers around him were always ringing for ideas and imagery. This led Xu to names like KAWS and Futura, artists in the street-to-Perrotin pipeline. The deeper Xu got into his first gallery programs, the more nuanced and committed his desire became. Xu replaced amassing shoes with small-run editions, and now he’s interested almost exclusively in the one-of-a-kind. I spy pieces by emerging and waitlisted artists like Genesis Belanger and Jonas Wood lurking in the background of our Zoom.

Xu swears by investing in artists who you’ve met. This makes his understanding of the work more multidimensional, but then he lists exceptions, like color-field genius Sam Gilliam, a favorite right now, which suggests the rule is more mission than restriction. For Xu, community is the filter through which he operates and buys: He likes his group chats with preview PDFs, art fairs as excuses for a run-in, the half-hour studio appointment that ends with a “two-hour lunch at a favorite place just up the street.” Sidebars are always welcome.

Xu pays this energy forward. Setting aside funds for small galleries is his number one tip, along with the axiom “trust your gut,” a tidbit he personally credits to his art-world confidante, the aforementioned Jon Gray, with whom he’s in constant communication. Gray is part of a matrix of friends that shape Xu’s participation and purchasing. In fact, Xu and I connected on the recommendation of curator Kyla McMillan, who has become an important interlocutor for Xu (and myself), introducing new artists into the thread and sharing expertise on what’s going on globally. Friends like Gray and McMillan, and the conversations (and sometimes parties) they foster, are paramount to how Xu assigns finance and time. When looking at work to purchase, materials and their resale value are also taken into consideration—but not worshiped. Themes, conscious and unconscious, are given plenty of elbow room. Perhaps that’s intuition speaking.

“At Felix [Art Fair], I was told by several gallerists that I have a very LA collection,” Xu says. “I didn’t know what that meant at first but maybe I am starting to.” What makes him so LA though isn’t the Sayre Gomez, the Friedrich Kunath and the Jonas Wood pieces, it’s his commitment to making meaning with others. The art leaders of LA have historically embraced the role of mentor, citizen, collaborator, co-conspirator. Xu only moved to Los Angeles three years ago, but his desire to make things better aligns him with the elders. I think about Lauren Halsey with her Summaeverythang Community Center, Lucy Bull’s desk gallery and the spaces that preceded them, those by Eve Fowler and Laura Owens, and Mark Bradford’s landmark Art + Practice, not to mention the brains behind my personal favorite LA outfit: Bel Ami. Wood’s poker nights even come to mind. Indeed, the city of angels has recruited another.

Danielle and Matthew Greenblatt

What I like most about Danielle and Matthew Greenblatt is that they only buy art they both love. In this way, their budding art collection, which already includes painters Sterling Ruby, Christina Quarles and Joseph Yaeger, serves as a living archive of their romance, and the obstacles they’ve overcome together. Matthew, who works in finance, is immunocompromised and spent more of the past decade than he’d like in hospitals. Danielle was always by his side. Therefore, mortality and its antecedents are a not so subconscious thread in the artworks they are drawn to. In fact, it was the resonance of Rashid Johnson’s “Anxious Man” series that they credit for their collecting habit. Matthew spotted the life-affirming work in a documentary and reached out to Hauser & Wirth with a cold call. To my revelation and theirs, they were offered the piece. But they passed on sticker shock alone. “I was intimidated by the number. It was the early days,” Danielle says. Matthew adds: “That was the one that got away. I think about it almost every morning. It was a lesson that if something is a stretch you can probably find a way to pay for it.”

Don’t worry, not only did they eventually buy a Johnson work, they have three. And on top of that, their first post-lockdown date was actually a masked studio visit with Johnson, a surprise organized by Danielle for Matthew, for him to finally get to ask “all my nerdy little questions.” Talking about art with each other, friends and acquaintances takes up most of their free time, and that’s how the New York-based couple likes it. When they aren’t at their desks (Danielle owns a fine-jewelry PR company), they are winding their way through galleries and museums. “Seesaw [app] is the greatest invention ever,” Matthew says. They’ll also splurge on international trips to see an exhibition. They went to Paris for two days to catch Jean-Michel Basquiat at LVMH. As COVID concerns wane, those plans are escalating again.

Seeing things in person is a critical tool for discovery, but so is Instagram, where Matthew parlays with like-minded collectors and curators as first and secondary sources for his intensive vetting. “He’s very research-oriented and I’m instinct-driven,” Danielle says. “He has the ability to balance my off-the-cuff, visceral reaction, which is great.” Matthew nods. “One of the best pieces of advice we ever got is that it’s not enough to love it,” he says. “Because you are going to love more than you can afford to [buy].” I find this funny coming from a couple whose ferocious love for each other and art is what brought the three of us together in the first place—and then I realize my mistake. Meaningful love requires action.

For Danielle and Matthew this means only buying things together, which requires them to spend a lot of their time looking at art side by side. The process has encouraged them to give back to the cities that are close to them. They are starting with ICA Boston. “We met and went to school in Boston. We felt it as a place where we could maximize our impact,” Danielle explains. Economy of scale is something that Matthew and Danielle seem particularly attuned to. They approach collecting with a marathon mindset: Pacing is important, and sometimes less is more.

Love alone is not enough, there has to be passion, and passion is best when shared. “It started with his grandmother taking us to shows and now it’s the other way around. We take her to everything and show her what we love and what we’re looking at and what’s happening,” Danielle says. “She’s seeing it through our eyes.”

James and Kimberly Elbaor

“This really started because my sister [Caroline] has zero interest in interest rate curves, it turns out,” says James Elbaor, founder of investment firm Marlton LLC, with a laugh. James identifies as a hardcore finance guy; Caroline Elbaor, an independent writer and curator, does not. Art became their bridge. It was something that pulled James out of his head and something that brought Caroline down to earth. “I hate to use the word currency between us because it’s not like Caro – line and I buy things together, but it is a language between us, a way for us to stay very close together. Because we’re in our mid-30s, it can be easy to get engrossed in work, in life, in kids. You lose touch with people that aren’t having that same experi – ence, and art has been this constant for Caroline and I to rebase our relationship.”

Art also became the foundation of another important relationship: James’s marriage to Kimberly Trautmann. His love of art was his secret weapon on his first few dates with the fellow financier, head of DRW Venture Capital. Armed with a list of galleries to see, assembled by Caroline, he knew that even if the date bombed, there would always be good art. Skip ahead 10 years, and the Elbaors now live in Chicago with kids and a burgeoning collection.

As self-described obsessive analysts and numbers people, the couple’s tastes surprise not because of what they buy, but why. They aren’t market hawks. They don’t blue-chip hunt—instead they stay loyal to their generation (millennials), and occasionally track down pieces they saw during those early strolls through New York together. Zombie formalism is an ongoing fascination. David Ostrowski, Lucy Dodd, Garth Weiser, Israel Lund, Lucien Smith. Ditto with Oscar Murillo, whose 2014 chocolate factory exhibition at David Zwirner was one of the first exhibitions they remember seeing together.

Retroactively seeking the souvenirs of young romance: What could be more personal? More enviable? Their introverted approach also shapes the way they buy. They shy away from most fairs and boards, putting their energies instead into extensive reading (they swear by Cultured, Elephant and Frieze) and dialogues with trusted advisors. The couple enlists two separate ones, Andrew Dubow and Gabriela Palmieri, who are powerful search engines and a way to sidestep some of the politicking they encountered when peeping turned into buying. “As we began looking for certain artists, we found the cold-calling wasn’t working anymore, which was frustrating,” James explains. “Once you get to a point where you are seeking out something very specific, working with an advisor makes total sense.”

At the moment they are both grooving on Jesse Mockrin from Night gallery; they also bought a Robert Nava from the LA gallery a year ago. They are open to new things as well as those from the early-to-mid-2010s. Not every acquisition has to be an agreement, but it does have to be purposeful, because they want to live with the work, and identify with that experience more than any other part of the process. The war in Ukraine has James returning to their William Macro, a piece which deals in censorship. Kimberly is caught up in the glow of the new Stephanie Hier in their dining room. “The painting is so detailed, technically excellent, and fresh,” says Kimberly. “Living with millennial female artists is important to how I think about building our collection and is something I’ve been able to share with James, broadening his aesthetic.”

Pushing one another is the name of the game. “Kim and I wouldn’t even say that we’re necessarily collectors as much as we are enjoyers,” James explains. “We have gone through this journey not because something’s just interesting to us, but because we like learning and it has become a way to bring our relationship, our relationships in general, closer.”

Jon Neidich

Brooke Garber Neidich, a jewelry designer and prominent member of the Whitney’s board, taught her children that to be an art patron you must be a contributor, not a consumer. So, after frequenting galas and art fairs in his early twenties, her son, Jon Neidich, knew he had to get more involved. The hospitality entrepreneur set his sights on Creative Time, whose over-the-top annual parties aligned with Neidich’s own budding interest in bringing cinematic plots back to New York nightlife. He specifically recalls a Creative Time gala in a Chinatown buffet hall where artists, socialites and dragon puppeteers were passing tequila and dancing the night away. “I remember thinking this certainly puts the fun into art,” Neidich says, cracking a smile.

Neidich has a similar life-affirming effect on the projects he touches, a quality that he eventually brought to the Creative Time board (family friend Anne Pasternak insisted Neidich make a name for himself before letting him join). In 2012, Neidich opened Acme night club on Great Jones Street after stints managing legendary clubs like Le Bain and the Boom Boom Room. According to a recent New York Times profile, Neidich is still helping get his mother and Pasternak’s friends into the glamorous basement space when they aren’t asking to go to his new one: a plush jazz club upstairs called The Nines. At Creative Time, Neidich’s powers for bringing people together made him a central shepherd in the search for a new director when Pasternak left for the Brooklyn Museum. He knew they found their new leader when they interviewed curator Justine Ludwig.

be inspirational both internally and externally. Somebody who was going to be respected by artists because that’s what the organization had been founded on,” Neidich says. “But what none of us realized at the time is that Justine also has this incredible natural ability as an executive director which has been the greatest gift.” Together, they’ve made Creative Time stronger than ever with Neidich playing chairman, and are currently gearing up for their most ambitious year yet with multi-city, career-defining projects by Charles Gaines and Taryn Simon. Five years in, it is only now that Neidich is finally starting to gain perspective. “I look back at my involvement in the organization as being something that I’m the most proud of,” he says.

It’s not the only reason he continues to stick around. He likes the close contact with the artists that Creative Time affords, as Neidich continues to find living and working with art inspirational. For instance, he describes a “wholesome” Tracey Emin neon reading “Trust Yourself” hung above his door as a kind of semiotic rabbit’s foot whose sacred energy was critical during the years-long build out of The Nines, his self-confessed biggest career risk to date. “Those words almost became a mantra,” Neidich says. “There were some very sleepless nights that were involved, where I’m pacing all over the apartment and all of the sudden having that work speak to me.”

For Neidich, work takes on more meaning with time. The Donald Sultan painting of smoke rings that decorated his childhood bedroom adorned the original Acme restaurant. His mother has never sold artworks and he plans to continue that legacy. “My advice is buy things that you want to live with and if you want to get involved in an organization, find one whose projects speak to you and do everything you can do,” he says, “When in doubt, write a check.”

Caio Twombly

You would think that a grandson of Cy Twombly—the canonical abstractionist—currently in the midst of building out an ambitious gallery in Florence would claim that art was his destiny, his birthright. But in school, Caio Twombly pursued other contact sports. He only made it to art later, on his own terms, and he plans to maintain them. As a collector, Twombly keeps himself on a short leash; he buys sparingly and purposefully. Ninety percent of the work is authored by artists Twombly works with at Spazio Amanita, his gallery. The common denominator? “It always feels like art that I would want to make, if I had the skill, if I had the talent and the possibility, if everything was aligned,” Twombly answers.

As a grade schooler and then teenager in Switzerland and Rome, Twombly bought drawings off of classmates. “When I was a kid, I was never impressed by technical drawing. I appreciated it, of course, but [what I liked] was very instinctive for me,” Twombly says. The same applies to his first purchase: a Robert Nava painting he spied on Instagram while in New York for university. “I’d [curated] some shows before that, but I wasn’t obsessive about looking everywhere. I hadn’t had something that really touched me as much as Robert’s works did,” Twombly shares. “For me, it was so immediately obvious. There was nothing I could compare it with. I had practically no knowledge of how it worked, it was completely instinctive.” Living with Nava’s work flipped something on. Afternoons of video games gave way to more committed exhibition planning and now have blossomed into a full gallery program.

My first brush with Twombly was during Frieze LA, where Amanita partnered with Young Collector List alum Jack Siebert on “I Do My Own Stunts,” featuring artists like Jenna Gribbon and Kylie Manning. The party raged all night. Amanita will maintain an international footprint with projects like this but the larger impact will surely be in Italy, where Twombly has the opportunity to create a bridge between the New York scene he knows and contemporary artists he’s meeting in Florence, Venice, Rome and beyond. “If I do shows with young artists in Florence, they have to be significant and done with care, but I also want everybody to have fun,” Twombly says. “Being in a place like Florence, you are afforded the liberty of being more emancipated from the professional and the socially constructed environments that you see. There’s going to be a paradigm shift here and I’m going to do this.”

Part of breaking the mold is creating new traditions. Amanita doesn’t limit itself to exhibition making and fairs. They host artist residencies and, in tandem with their seasonal programming, have created a parallel permanent collection that gives a sense of object permanence to a project that is otherwise infinitely flexible and open. “It’s something that artists are attracted to and it creates more of a sanctuary for what we’re trying to foster,” Twombly says. “For me, it’s a place where I can concretely see what we’re doing, a chronological narrative of our development.”

Jeff Magid

When Jeff Magid bought a Henry Taylor painting he didn’t know it was going to become a kind of reliquary of his time in Los Angeles. Magid acted on instinct, the same gut feeling that had sent the young musician westward from his East Coast roots. Someone had told Magid fate lived in Los Angeles and he went to look for it. But he unlocked something more peculiar: contemporary art. He still laughs when recounting an all-artist poker game at the behest of Slater Bradley. “At the time I would say to people, ‘Hey, this is my friend Slater Bradley,’ He’s a modern artist,’” he says. “I didn’t know the difference between modern and contemporary art.” Bradley took modernity in stride–acting as an early guardian angel by introducing Magid to names like Taylor and Charles Ray. That’s all it took. Magid fell down the rabbit hole. “One of the things that inspired me about Henry was he didn’t seem to care about hierarchy,” Magid recalls of those early days. “He welcomed everyone.”

Inclusivity is a tradition Magid has sought to keep front and center in his own movement through the arts. His collection follows a payit-forward logic partially informed by his own experiences as a young artist. That is to say he recognizes the power of a vote and the tip in the scale it can be at the right moment. “I hope to be the person that stands up early on,” Magid says. “So many times, that’s one of the only things missing from a great artist getting the recognition they deserve.” Speaking to artists about the practices that lift them up and challenge them is a part of identifying the right voices to advocate for. He can cite lineages of discovery. Taylor to Noah Davis. Kylie Manning to Doron Langberg. Tomm ElSaieh and Diego Singh to Constanza Schaffner. Inevitably perhaps, his holdings have a distinctive West Coast twang (Taylor, Davis, Ray, Bradley), but the plot is always evolving. Magid, for instance, recently helped the Hammer Museum acquire a work by British abstract painter Jadé Fadojutimi, whom he is a strong advocate for.

Facilitating these kinds of institutional purchases is something Magid makes a concerted effort to do because it can be a small but tangible part of helping institutions become more representative of the publics they serve. He sits on the Emerging Art Fund committee at MOCA LA, but has also helped the ICA Miami and Los Angeles County Museum of Art bring new works into their permanent collections. In 2022, Magid plans to take his support a step further. He’s opening his own exhibition space and artist residency in Mexico City. The broad strokes include experimental time and real estate for artists and curators alike to try out the things they haven’t done before with no market pressure on top. The main aspiration is to pilot ways of dismantling the gap between art space and street. “I hope to change the experience for those whose first impression of the art world is that it’s all about who is important,” Magid says. “I want to be part of making art inclusive.”

Harry Hu

There are many mysterious things about Harry Hu but the most striking is his talent for turning inertia into momentum. Hanging out with Hu makes me feel like I’ve been happily subsumed into a cartoon snowball; a one-on-one inevitably expands into three or four or five and then you’re at an eight-person, two-hour lunch trying to figure out how many Uber XLs you’ll need to get everyone to a Whitney Biennial walkthrough. Will everyone be able to get in? Hu, a Whitney Museum patron, smiles: “Of course.” Meanwhile, plans for studio visits and phone number exchanges crowd the door, as one invitation opens into another. Hu’s generosity of spirit is contagious and ultimately the engine that makes it all run. Our first meeting was supposed to be a photoshoot but it bled over into an entire afternoon which would have tumbled into evening if I hadn’t needed to return to my desk. The world is Hu’s office, and this collision of friends and strangers is his preferred daily routine. Art and relationships are given the liberty to go at their own pace. It is not a 9 to 5. “We are all pieces of the art world,” Hu says. “If we got together we could see the whole map. That is why I’m always traveling. That’s why I put myself out there.”

Hu lives mostly between Los Angeles, his home, and New York, where he’s moving more full time this summer. He’d been spending a week at a time in the city for months before pulling the trigger. Hu likes the energy of New York and the ease of getting to the next destination. He’s a voracious gallery goer. “I want to see everything,” he says.

His friends are also increasingly in New York, including Anna Park, whose studio we crash. There’s a gigantic Vegas-themed triptych by the young Blum & Poe painter loosely based on a casino weekend they spent with Park’s boyfriend, painter Mike Lee. This work is personal to Hu in a literal way; but everything he buys or participates in has some nugget of real connection buried inside. He likes commissions. He likes Alex Shulan at Lomex, Andrew Dubow at Ramiken and gallerist Matthew Brown. He likes The Hairy Who (at first for the joke and now the aesthetics). He only does primary markets.

Hu is all in on artist’s artists. He values a laugh. He doesn’t feel connected to what everyone else has. He believes in the power of curators and institutions. Hu wants to deal in things that are complicated and truly rare, friendships included. In fact, he started a non-profit artists residency (Horizon) with a couple of friends (Jason Li and May Xue) during the pandemic and then hired one of the most prescient curators, Christopher Y. Lew (formerly of the Whitney) to lead its curatorial vision. Lew in turn picked two curators, Wassan AlKhudhairi and María Elena Ortiz, and will continue to do so annually as part of Horizon. This core group will select the four artists they plan to host during the course of a year. They started with Laurie Kang. Next is Sara Cwynar and then Phillip John Velasco Gabriel.

He pauses on Gabriel. “For me, [collecting] is all about the relationship of the artist, the story of my life and how it touches me as a painting or as a sculpture, why are they doing this?” Hu tells me, continuing: “That’s why I want to get a work home, to start looking at it more, to explore and feel different things,” he says. “Like Phillip’s paintings, for example, are so visually saturated and unlike anything I’ve seen before. I look and look again. I have to have it.”

in your life?

in your life?