“When I first started the gallery, I was like, ‘I only want to work with the people that I get on with. I don't want to work with any assholes.’ The process of putting on an exhibition is so intimate. If there’s tension between you and the artist, I don't ever think that it's conducive to having a successful show,” says Rose Easton.

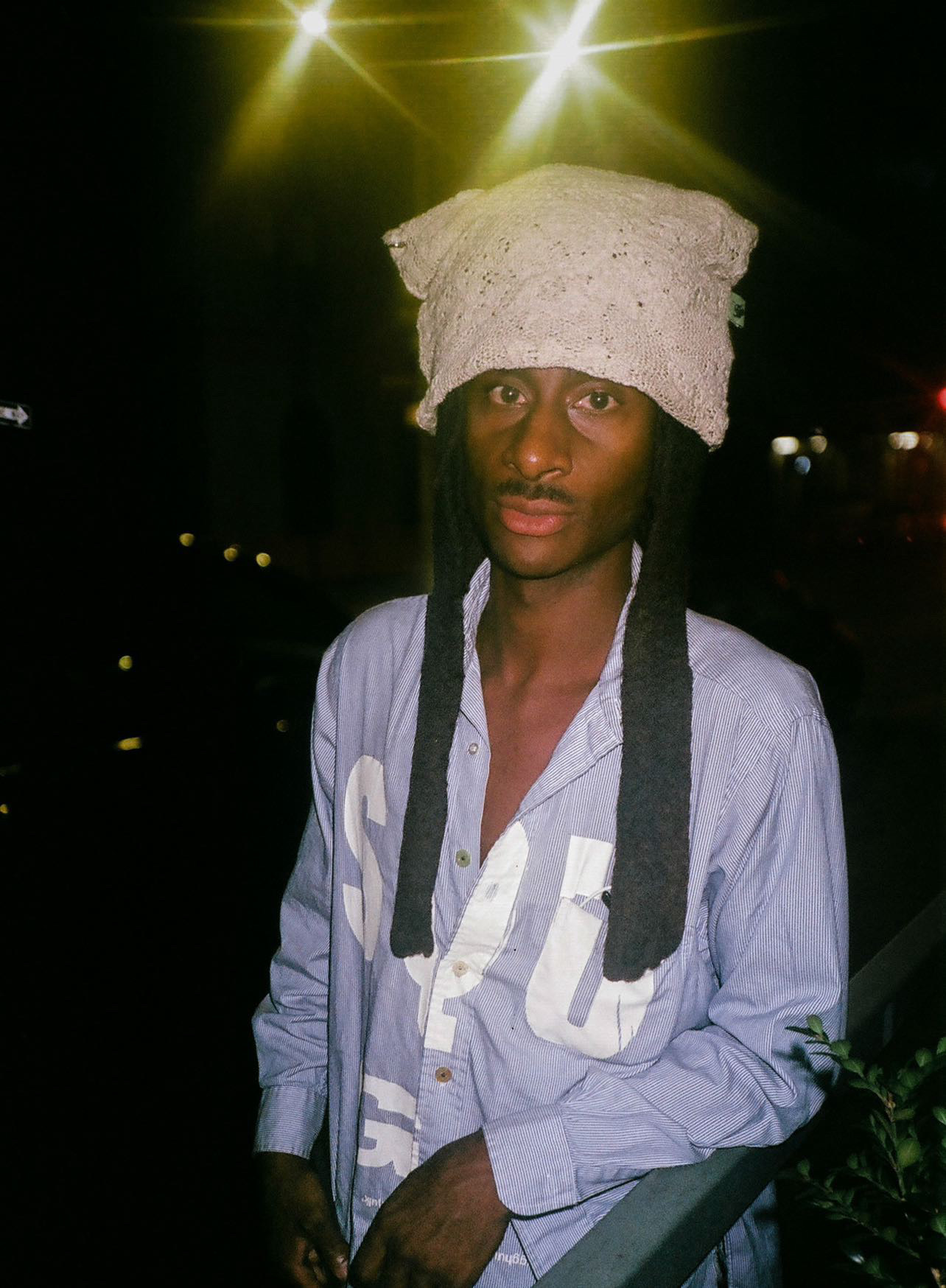

The London-based gallerist—whose eponymous space opened in 2021 and has since highlighted the work of artists including Lotte Andersen, Eva Gold, Arlette, and Shamiran Istifan—may have met her match in Jan Gatewood. Easton first spotted the mixed-media darling’s work in a show with Silke Lindner last spring. The Tribeca gallery’s floor was punctuated by over 100 pieces of fabric (bearing the artist’s likeness and free for the taking), and its walls featured a menagerie of animal characters, depicted in various states of fragmentation and accompanied by titles that oscillated between the confessional and the clinical. Impressed by Gatewood’s caustic yet profound handling of “more nuanced subjects,” and the works’ ability to transcend their papered surfaces, becoming almost sculptural, Easton arranged a studio visit.

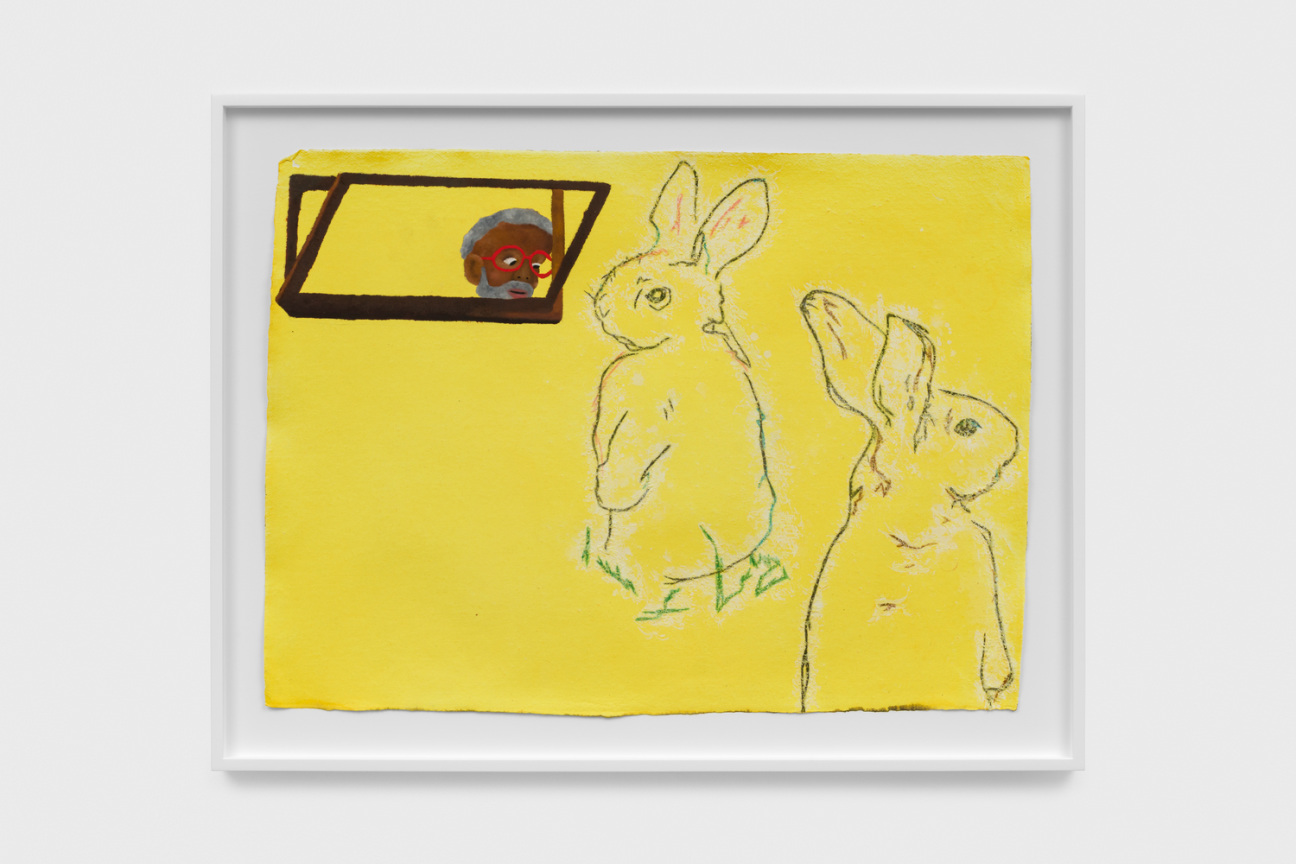

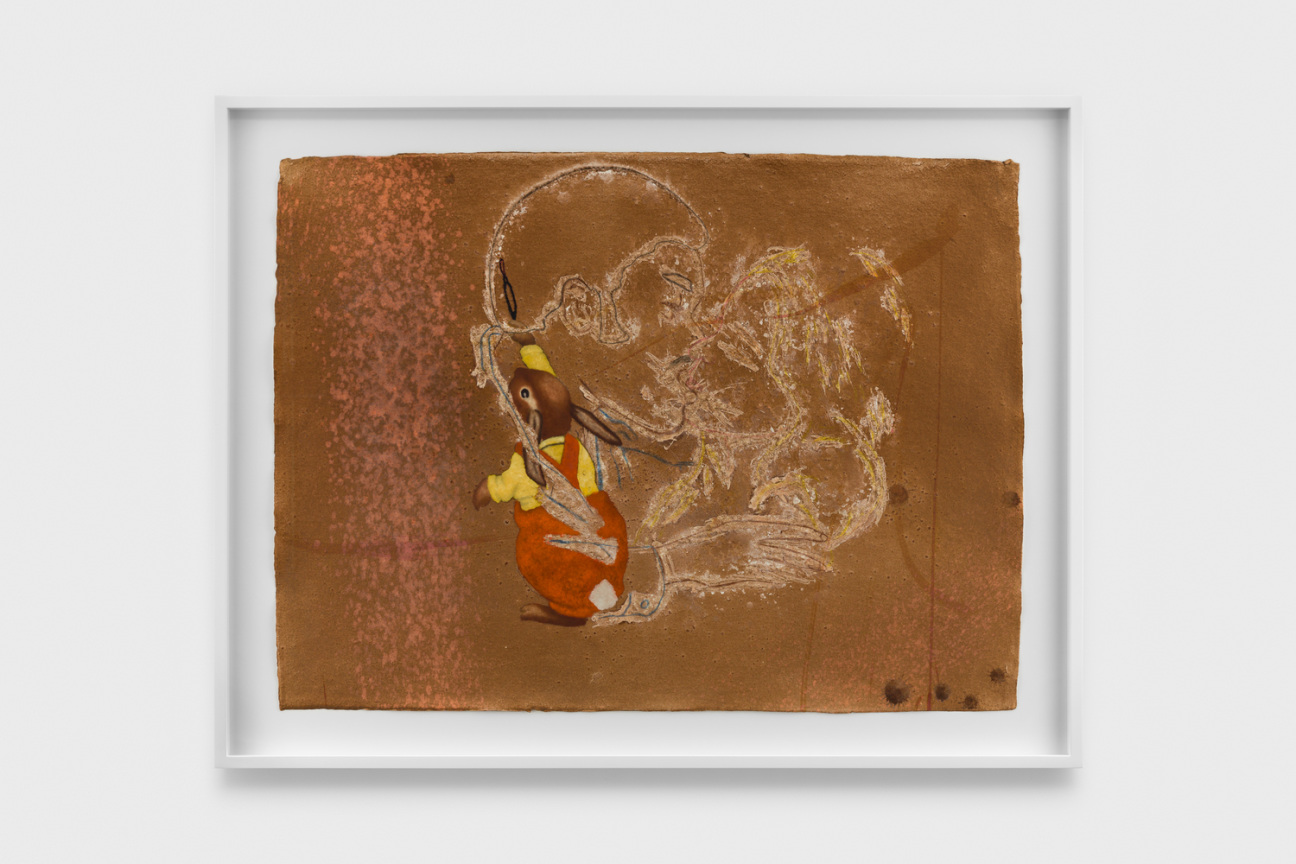

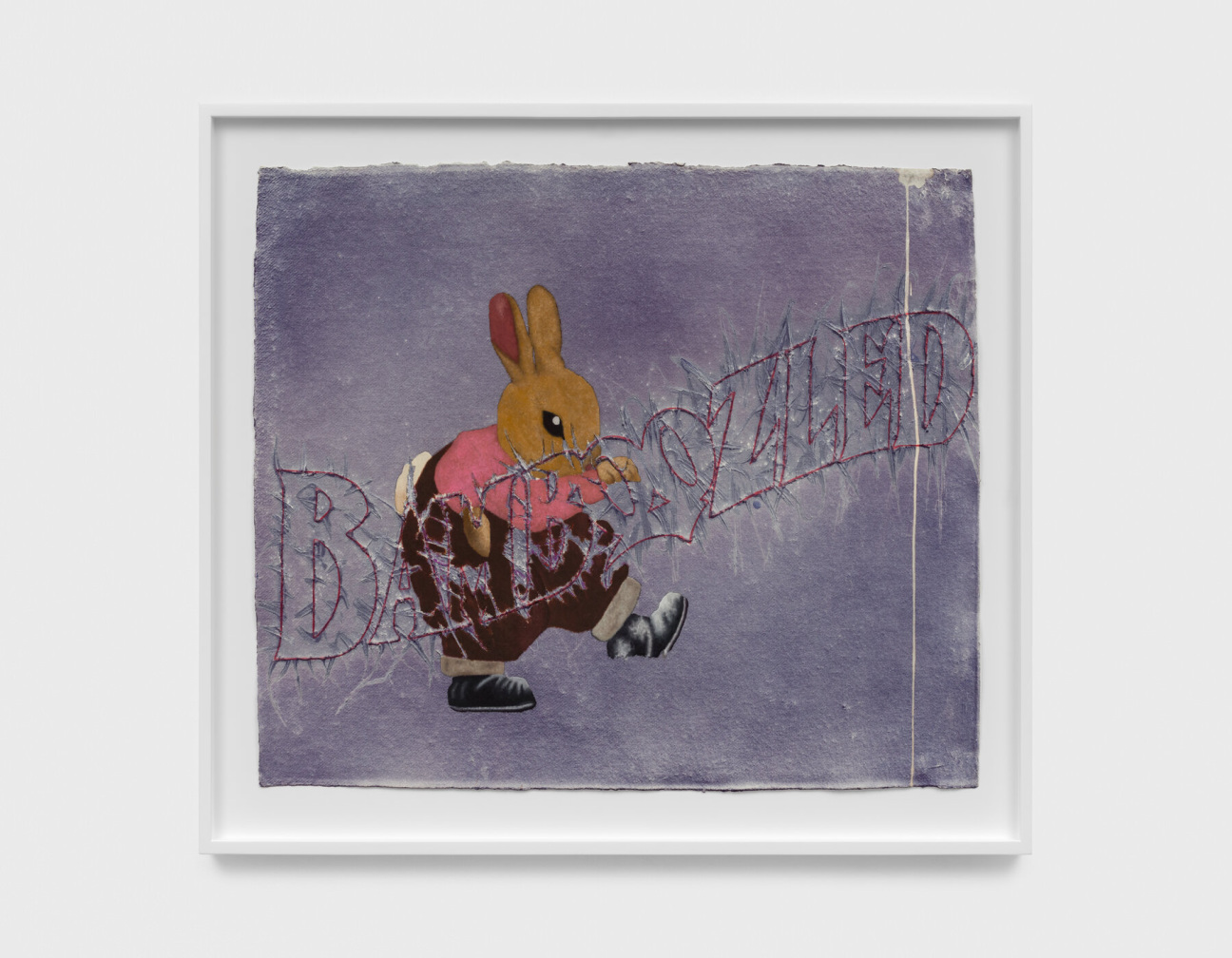

Less than a year later, the Los Angeles-based artist opened “Group Relations,” on view at Rose Easton through March 2. In the gallery’s compact white cube, Gatewood has managed to weave references as discrete as Gone with the Wind, punk icon Poly Styrene, and the psychoanalytic theory the show’s title cites. Rabbits, and their anthropomorphized relatives Br’er Rabbit and Bugs Bunny, are a throughline in the 14 drawings featured. As with past works, Gatewood seems interested in representing these creatures not for their own sake but for what they say about us, a connection made literal with the inclusion of human figures in several of the pieces.

Another human—the artist Andrea Fraser—is present too, an image of her printed on the pillows that pepper the room. Known for her interrogation of the powers that be, Fraser is an apt patron saint for an exhibition that probes the contours of how we see and sell ourselves. To mark the artist's U.K. debut, Gatewood and Easton sat down to talk free artwork, oral traditions, and self-awareness.

Rose Easton: Jan, we met because I saw your work in a Silke Lindner show last year online, and the way that you use animal subjects to dance around more nuanced subjects, which some people can approach quite heavy-handedly, was attractive to me. We haven't really shown that much painting at the gallery because I find it sometimes harder to engage with, but I think your work occupies the space between drawing, painting, and sculpture. Can you tell me about your introduction to the human figure?

Jan Gatewood: In my practice thus far, I’ve used animal figuration to renegotiate certain conversations around identity politics. The production of this exhibition started with a critical observation of some recent ways in which identity has been commodified, specifically in figurative painting. Due to these observations, I felt it made sense to now include human figuration in my work. I wanted the subject matter to be accessible so I introduced a wide range of references including The Boondocks, David Hammons, and Bamboozled, to name a few. I wanted all of my usage [of the human form] to be very intentional. The references I'm making in the drawings in the show all participate in complex dialogue surrounding race and representation.

Easton: Even though you're using this body of work as a way to address and, to some extent, critique this lack of criticality around race and representation, you're not trying to—and this is the wording you've used [in your notes]—“exalt myself into a position of being a morally good representative. I'm aiming to materialize self-awareness.”

Gatewood: I was really wanting to think about what happens after you decide to be a representative of your race by making money off of certain images. I wanted to make sure I'm implicated across the board while also staying in alignment with the concerns that I normally have in my work. The concerns are still the same, but I'm being more direct in the show and publicly with my discussion of the work. My joke to myself is that [my pieces] are trying to do the impossible, which is to create an object that seamlessly combines abstraction, figuration, and text. A way in which this is actualized is through several ways of thinking about utilizing resistance.

Easton: When we're talking about making sure you're implicated on many levels, first, it's your work. Of course, you're implicated. Second, these are all references specific to you in terms of how you've pulled from literature, music, popular culture, other painters, other American artists even. It's interesting to talk about the way you use your own body to make the artwork itself. I guess you would normally say the artist’s hand is present, but for you, the artist's hair is present.

Gatewood: When I started [to work on] the show, I wanted all of the drawings to be made in the same way. I was thinking, What is a Black artwork? How can I make the blackest gestures? So I was like, “Oh, because I don't use any brushes in my work. I could use my hair.” It's a terrible joke—a “hairbrush.” A lot of them were supposed to start with making gestures with my hair by attaching a sponge to my hair and then moving my head around the paper. There's a few of them that started that way, but I wanted to allow myself to deviate from that.

But having my body be present and implicated in various ways was crucial. Sometimes I like the idea of putting what's in my body in the work. If I'm eating certain food that has juices, or drinking matcha, I combine those food materials with materials that are more consistent in my work to create different chemical reactions on the paper. This is done in part to support my ideas of mark-making that could only come from me.

Easton: A lot of the show reckons with this commodification of Black artists, and what that kind of push and pull is for you. Because it's literally using your own personhood to negotiate with the idea that personhood has been commodified within the art world.

Gatewood: A solution I came to in this work was to use my drawings to point towards moments in art and culture that contain complex racial dialogue as a reminder to viewers and makers of what can be and has been done. I guess you could say my personhood was used physically, mentally, etc. to attempt to accomplish that.

Easton: There's also a collaborative element to your work—you've invited Justin Chance to write the text, and Andrea Fraser’s face decorates the floor in these free artworks that are cushions… I wonder if you see these as a form of collaboration or appropriation?

Gatewood: It's a mix of the two. It's a reconciliation with the way originality might be thought of in art-making. All of our thoughts and works exist off the backs and lineage of other artists. Instead of suppressing that, it's more interesting to make it obvious and invite all these people into my exhibition.

Easton: Let’s talk a bit about "Group Relations" and Andrea Fraser and how that ties in.

Gatewood: Fraser is known for institutional critique. She's someone that's been really present in my art journey thus far. One of my old roommates and good friends, the artist Michael Bala, had her at UCLA, and he used to just give me all of his syllabi. I still have a course she teaches in my studio called “Introduction to New Genres.” I love the way she speaks about criticism and empathy, and how she takes these thoughts and formulates them into such concise and deep artworks that also play with morality. I found out about group relations through her art practice, and I felt like this was the perfect framework to apply to my thinking about how representation could flatten experience. I also love how she implicates herself deeply within her works. She says that you can't critique without empathy; that goes back to me implicating myself in the things I'm critiquing.

Group relations is an English psychoanalytic theory that helps people unpack their biases in groups. The main goal of the theory is a thing called a “conference,” which is basically a group of people talking. That's what I wanted to accomplish with the show, to get groups of people talking about the ways in which marginalized people capitalize via depictions of their identity and what (if any) are the consequences and responsibilities of those artworks. I wanted to use the Black male American identity specifically because that's what I know and what I can speak from; however, this is a conversation that's applicable to any marginalized person who has seen their identity commodified in art, especially in recent years.

Easton: A key part of the show is the recurring figure of Br’er Rabbit. It’s also an anchor in the text Justin has written. So can you tell us a bit about the figure?

Gatewood: Br’er Rabbit is an African-American oral tradition with roots in Africa and the American south. It's the story of an anthropomorphic rabbit in and around slave plantations, which uses wit, humor, and agility to achieve what he views as successes. This is a story that I and a lot of other people have grown up with, and I felt like was the perfect figure that could help guide discussion in my show.

I wanted something that deals with morality, something that deals with Americanness and also Black representation, but also obviously an animal. I also loved how the story is crucial to American pop culture. The story of Br’er Rabbit eventually became a [1946] film called Song of the South, which is one of the first live-action films that Disney made, and it helped solidify problematic archetypes that are still in use to this day.

Easton: The Br’er Rabbit is [part of] an oral tradition that was carried over through transatlantic slavery. Something Arthur Jafa said that’s always stuck with me is the reason why oral traditions are so strong in African American culture is that enslaved Africans could only carry that which was inside, or of, their body. The only way traditions could be retained is if they could be passed down through the body—as dance, story, or song. And you're using your body to kind of regurgitate this oral tradition. All of it starts syncing up. And Br’er Rabbit—if people come to understand what that is outside of popular culture—is using a light touch to explain something much more historically fucked.

Gatewood: I feel like that's my interest in comedy, that sensibility shining through, like sugar in the medicine approach, where you just use humor to open people up, and then that way you can have whatever kind of chat you want.

Easton: Do you want to talk about the free artwork?

Gatewood: That was something I started doing to subvert my understanding of the way exhibitions typically work. I found it unfair that few people who have the excess means to acquire an artwork get to physically own an object from the show. I want to give something to anyone who’s able or interested in coming to see my shows. I like playing with the way value works, and I also like using the floor and other parts of the gallery to heighten my concerns.

A personal criteria I have for a good show is, “Do I feel like I can relax in the space?” Artworks change drastically when you can relax and look at them. I wanted to pair those feelings with an image of Andrea Fraser, who almost is an image of institutional critique herself. All of this resulted in pillows populating the gallery floor. I hoped it would be a fun and playful way to loosely tie everything together.

"Group Relations" by Jan Gatewood is on view through March 2, 2024 at Rose Easton in London.

in your life?

in your life?