At the dawn of the digital century, Harun Farocki, who once described himself as “the best known unknown filmmaker in Germany,” coined the term “operational image.” This class of pictures did not depict an object for the sake of human legibility or entertainment, but rather to deliver information to (and work for) a machine—whether it be a drone or an ultrasound. Farocki’s concept proved widely influential in a world increasingly synonymous with surveillance, and it is one of the fundamental premises of Nina Hartmann’s new solo show at Silke Lindner in New York. “There’s an inherent truth to this format, and I started thinking about this idea of ‘proof’ in mediums,” says the Miami-born, Queens-based artist. “I want the work to disrupt a lot of these systems of delivering data, and perhaps suggest a reevaluation of how we intake information.”

Hartmann manipulated—through the use of AI and other transformative tools—and injected the series of encaustic and resin sculptures made for the exhibition with photographic material “from official government pamphlets, leaflets, and press kits” as well as “alternative sources of information like message boards and UFO believer websites.” The former category was originally tasked with providing evidence to back specific narratives around contentious chapters in history, such as the Roswell Incident or Manhattan Project. Although the 33-year-old Yale MFA graduate largely keeps mum about the images’ exact origin, she admits, “There are breadcrumbs within the titles and imagery … It’s up to the viewer whether they want to start their own line of research using these cues.” Ahead of the opening of “Soft Power” this evening, Hartmann let CULTURED in on a few of her enigmatic methods.

CULTURED: How would you describe yourself?

Nina Hartmann: A multi-disciplinary artist existing somewhere between painting, sculpture, and photography. Persistently curious, probably always going through an existential crisis on some level. Always open to and humbled by the world’s synchronicity and ability to reveal new truths. Skeptical of taught realities and accepted knowledge. Equally nihilistic and empathetic. Enjoys a good dive bar.

CULTURED: You recently received an MFA from Yale University. What aspect of grad school did you find the most challenging and/or enlightening?

Hartmann: My time at Yale was equally great and psychically difficult. I’m grateful for the community I found there and the space and understanding my classmates and advisors gave me while I tried to push my work in new and uncertain directions. While in school, I became really interested in the indoctrination processes that happen in Ivy League spaces for future politicians of America—particularly the Global Affairs and Political Science departments. It felt like a really unique opportunity to experience the curriculum and principles taught in the spaces that so many politicians are molded in, because the whole thing is so clouded in mystery and secrecy. I attempted to get into the Skull & Bones building multiple times but didn’t have any luck.

I tried to take advantage of the law and military library collections and expose myself to new bodies of material I hadn’t had access to before. Part of my practice is trying to deconstruct complex and intentionally opaque systems of dissemination and influence in order to try and understand their function. Some of the tactics I’ve been most interested in are repetition, allure, mysticism, redaction, suppression, and disinformation. The body of work starts to function as its own unique system, but also mimics the systems I’m attempting to dismantle.

CULTURED: What was your last research spiral? Have you ever hit a moment in your information gathering where you’ve felt you’ve gone too far?

Hartmann: I like to think of my work as being embedded with universal frequencies of collective thought as an attempt to harness some part of the zeitgeist. But equally, the work is layered with filters of my own subjective experience and driven by my personal interests. I don’t see the way I collect and absorb information as anthropological, but more as an immersive and affective experience.

There can be moments where my mental health is affected by spaces I find myself in on the Internet, or in learning about difficult histories—it’s a big part of the work. There are times I need to take a step back or pursue lighter subject matter in order to make my practice more sustainable, but it can be a difficult balance since I’m naturally drawn to darker themes.

I have been consistently fascinated by attempts made by the U.S. government to harness mysticism, mind control, and psychic abilities to be used as weapons in military operations. This kind of technology development often has conspiratorial ties to academic spaces, most notably theories about MK-Ultra’s involvement at Harvard, where students were allegedly given LSD and controversial psychological testing.

I started digging around the Yale archive during my time there and was working through an archive on Dr. Jose Delgado, a former neuropsychology professor at Yale. While at the university, Delgado conducted tests that attempted to alter brain function (basically mind control) through electrical stimulation, and famously demonstrated his alleged ability to do so using a charging bull in a bullring in Spain. He claimed to have altered the bull’s behavior through these methods. I’m not sure where the project will take me yet, but I’m looking forward to diving back into it and seeing what connections I can find.

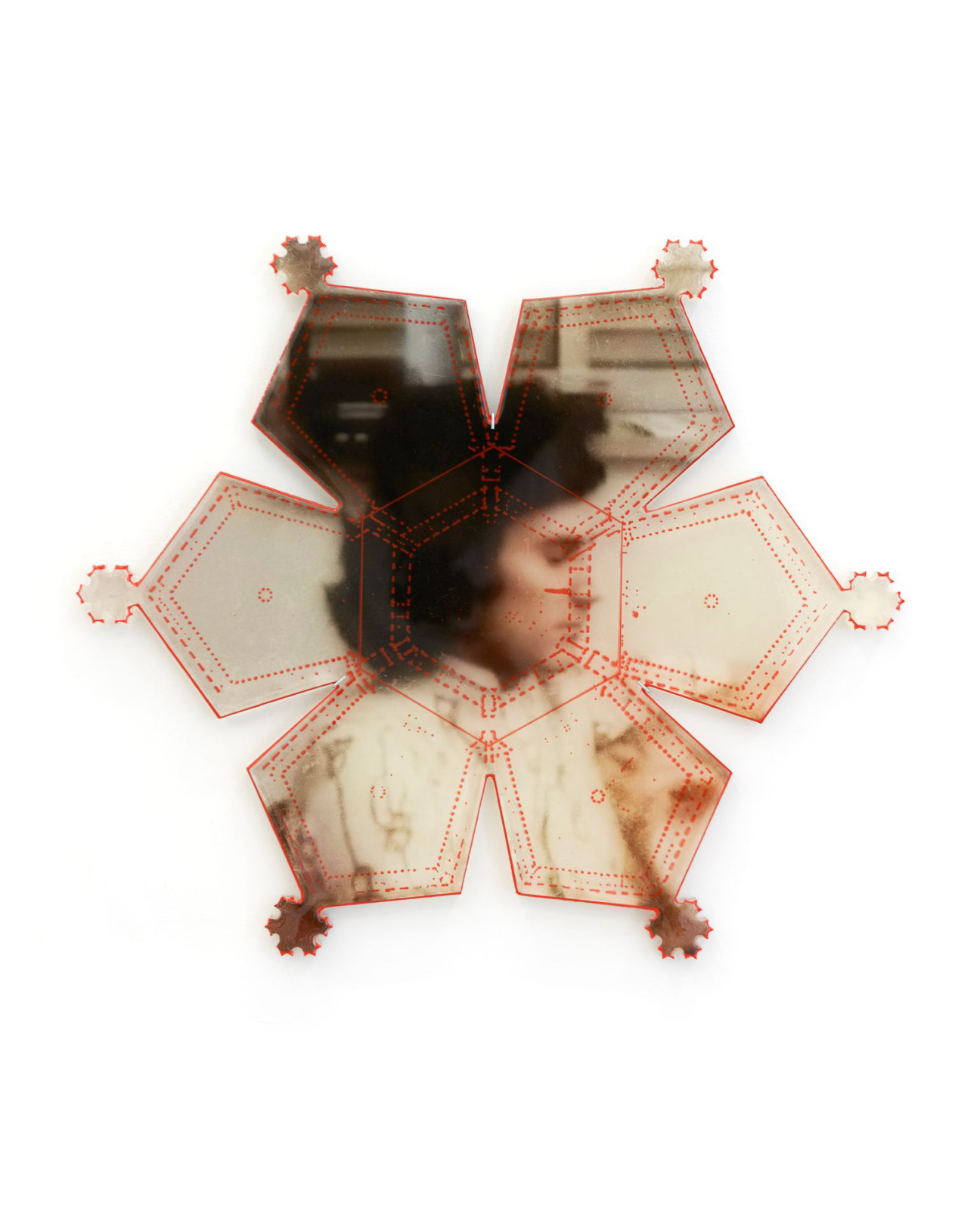

CULTURED: Your sculptures have taken the form of stars, keyholes, plier tips, Rorschach test-like butterflies, gravestones, outdoor plaques… How do you land on their shape?

Hartmann: Some of the shapes are a direct translation of existing symbols or objects, but most of them are an amalgamation of absorbed content. For this body of work, I tried to treat my brain as an algorithm, in a way, to create some of the shapes. I intentionally took in curated information to the point of slight exhaustion or disassociation, and then would shift to drawing or collaging after absorbing the material.

So, in a day I might look at numerous kabbalistic diagrams, diagrams explaining theories of social constructionism, and a PowerPoint presentation on how to create successful infographics. The goal is to pick up common threads between all of this subject matter and create something through the filter of my subconscious.

It’s kind of like automatic drawing with intentional brain conditioning. It felt relevant for me to work this way since so much information is being delivered to us through algorithms and AI created material. The star shape in Triangle Logick is something that presented itself as a pattern cut out of an unstretched latex piece I made. So many of the shapes are in conversation with each other in some way, they might be a negative or inverted version of another piece. The body of work starts to function as its own unique system, with each shape working like a letter in an alphabet. I try to weave in a lot of subliminal connections into the work.

CULTURED: Who are your heroes?

Hartmann: Some people that had a huge influence on me are Cady Noland, Robert Rauschenberg, Adrian Piper, Nick Cave (musician), and Carl Jung. I grew up in punk and experimental music scenes and was influenced by industrial bands like Throbbing Gristle, especially with resampling images. I think my work also functions in the vein of a lot of post-structuralist thought and writing. I've been influenced by Michel Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari, Derrida. Also love Ariella Azoulay. And other thinkers that exist outside of the box and beyond classification: Antonin Artaud, Georges Bataille, Wilhelm Reich, and Jack Parsons.

CULTURED: The Silke Lindner show “explores the functionality and malleability of proof in a modern day information age.” The word proof can refer to evidence, but also to a test or trial, like for a book or an engraving. What are you testing with this show?

Hartmann: For this body of work, I worked largely from official government pamphlets, leaflets, and press kits that serve as supposedly transparent, often about controversial subjects, events of interest like the Roswell Incident or the Manhattan Project. One of the collections of photography came from a book that the U.S. Air Force released in an attempt to disprove UFO sightings that happened near Roswell in the 1940s.

The book offers photographic documentation of military tests that involved throwing human-sized dummies out of planes to test parachute technology, hoping to provide an explanation of the sightings. I was also looking at pamphlets created by the Department of Energy in response to criticism about the environmental and health harm done during nuclear testing. These materials present information with a clear intent of supporting a particular narrative through the use of photographic evidence as a kind of indisputable proof.

By using these photographs which offer “proof” through their photographic or documentative nature, I wanted to disrupt the chain of dissemination that occurs. I sometimes used AI to doctor the images, at times altering color or generating new content. It’s questioning modes of authorship; there’s definitely elements of trickery and playfulness involved.

CULTURED: How do you grapple with the gaps of knowledge between the originators of the content you’re using, yourself, and your audience?

Hartmann: It’s a constant negotiation and fluctuation of how much information I divulge for a body of work or a single piece. There’s an inherent power dynamic between the artist and viewer: the artist knows the sources of the material and can use obfuscation as a tool. I think that ambiguity can create a space for potential personal experience and meaning. I try to use photographs that function like modern iconography or symbols in some ways, hoping to invoke universal mythologies or themes that are relevant.

in your life?

in your life?