Qualeasha Wood

A textile artist for the Internet age, Wood broke art world records in 2022 as one of the youngest artists to have a work acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

Filmmaker Cheryl Dunye!

How did you encounter Dunye’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

I was taking a Black cinema class, ironically taught by a white woman. One of the first films we saw in the class was The Watermelon Woman, 1996, which Cheryl Dunye wrote, directed, and acted in. I hadn't at that point seen a Black lesbian perspective in film, especially one free from the heterosexual gaze. I felt, and still feel today that a lot of the art and entertainment industry produces queer art for straight audiences. Cheryl’s work is a tribute to Black lesbian lives, honoring our history and future.

How has her work shaped yours?

It was inspiring to watch Cheryl be sort of a one-man show in her earlier works. I relate to that a lot within my own practice—the idea of starting with the self and building a world that expands beyond a singular perspective. As a queer Black woman, I find myself referencing the storytelling and world-building of Cheryl Dunye as I create worlds to depict and reimagine Black femme embodiment.

Through her filmmaking, Cheryl shares with us the potential of taking our truths and vulnerability and reshaping them into something disruptive—to capitalism, to white supremacy, to homophobia—a radical self-love that threatens the very core of our society.

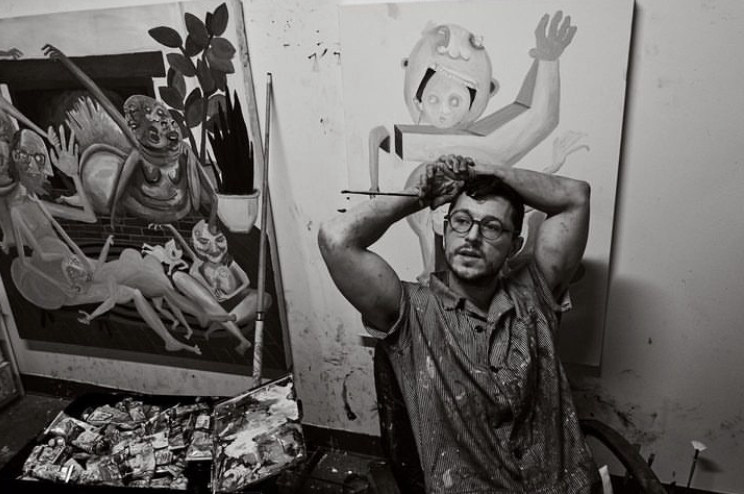

RF. Alvarez

The 35-year-old painter left Texas at 18 with the firm intention of never returning, but his homecoming has proved a rich inspiration for his personal, powerful oeuvre.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

Patrick Angus. He was a contemporary of [David] Hockney’s, but as opposed to Hockney's bright California outdoor space, Angus was interested in depicting a world of very New York interior spaces and gay bars—places that exist in the shadows. His work reads like enticing, lonely, contemplative, beautiful memories.

How did you encounter Angus’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

I was gifted a book of his work by my husband, who knows way more about art history than I do despite working in medicine.

How has his work shaped yours?

Angus is the reason I paint my direct surroundings. My work has become increasingly personal, and I owe that to him—the immediacy of his work is something I am constantly striving for.

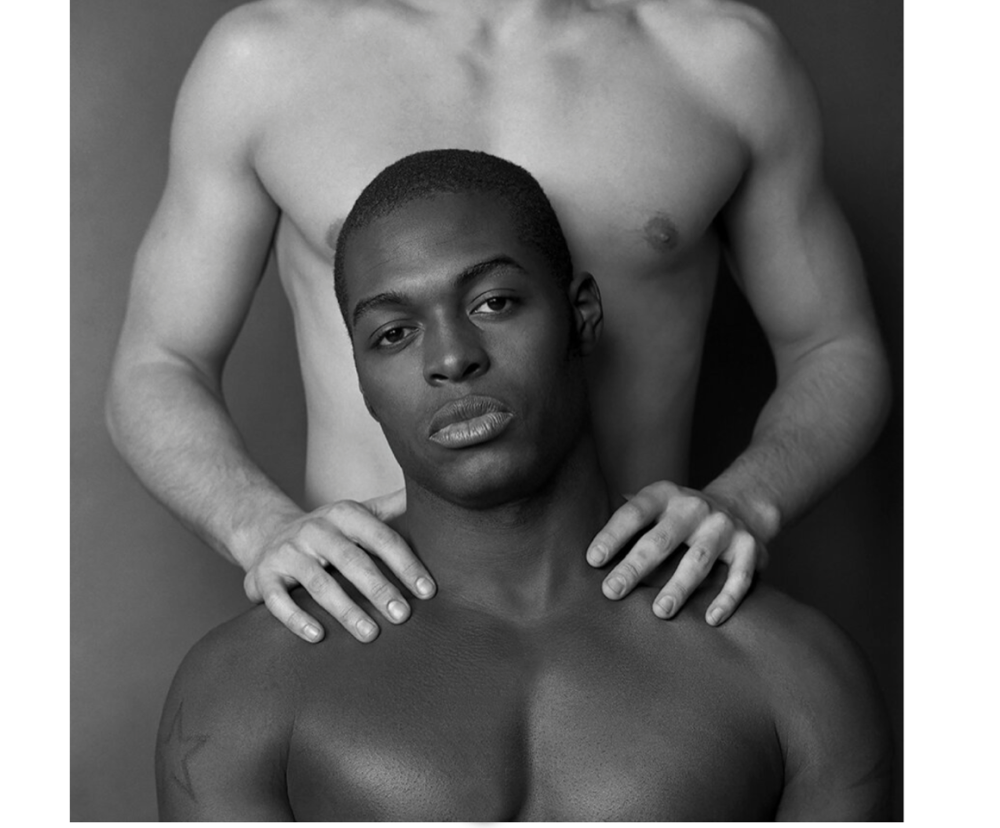

Doron Langberg

The Israel-born, New York-based artist makes fleshy, figurative paintings that vibrate with the sensuality of queer passion and friendship.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

Avram Finkelstein, a legendary artist, activist, writer, and curator. Avram founded the Silence = Death collective, which designed the iconic poster and took part in Gran Fury, the visual side of ACT UP, the revolutionary political group working to end AIDS. Today, Avram is making incredible large-scale drawings from memory of his experiences with family and lovers.

How did you encounter Finkelstein’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

Avram was my mentor at the Queer Art Mentorship program. As he’s a conceptual artist working mostly with collectives, we were an unlikely pairing, but our monthly studio visits meant so much to me. Avram is also Jewish with a family history scarred by the Holocaust, and seeing how he connected his Jewish and queer experiences through his work was very inspiring to me.

How has his work shaped yours?

Our time working together was at an important juncture in my practice where I was looking to expand my subject matter and my idea of what making work about queerness meant. Avram pushed me to look beyond the sexual subject matter and think about the infinite ways in which queerness takes shape in my life.

Nao Bustamante

The cult interdisciplinary artist is known for works as riotous as Indig/urrito, 1992, where she strapped a burrito onto her hips and asked white men to apologize for years of Indigenous oppression by taking a bite out of it; or more recently, “Grave Gallery,” the art space she launched this spring on a funeral plot in Los Angeles’s Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

Remy Charlip. He was primarily a dancer and was moving into the realm of performance. He previously danced with John Cage and was living in San Francisco in this wonderful apartment and was a really great community member and a gentle soul. He would host these cool potlucks in his house, where we all had to take off our shoes. He had a really clean floor, and there would be stretching and movement happening while we were hanging out with him.

How did you encounter Charlip’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

He was a well-known children’s book author; I mostly knew him through the performance and dance world. He once gave me one of his children's books called, Fortunately, 1964. “Fortunately, it’s my birthday. Unfortunately, no one remembered.” It’s this funny book that moves through fortunate and unfortunate scenarios, and I think it set my mind on a good path. I never read his books as a kid, but as an artist, there are a lot of fortunate and unfortunate scenarios we find ourselves in.

He had such great stories about traveling in a VW van with John Cage, his nights out dancing, and his life as a young artist. It was cool to proverbially be at the feet of an older artist and hear about their very queer life. He had a strong connection to the land; I don’t know if he was associated with the Radical Faeries but he was like a prototype.

Miguel Gutierrez

The Brooklyn-based performance artist, choreographer, and podcaster creates work that bridges the realms of queer experience, identity politics, and art world criticism.

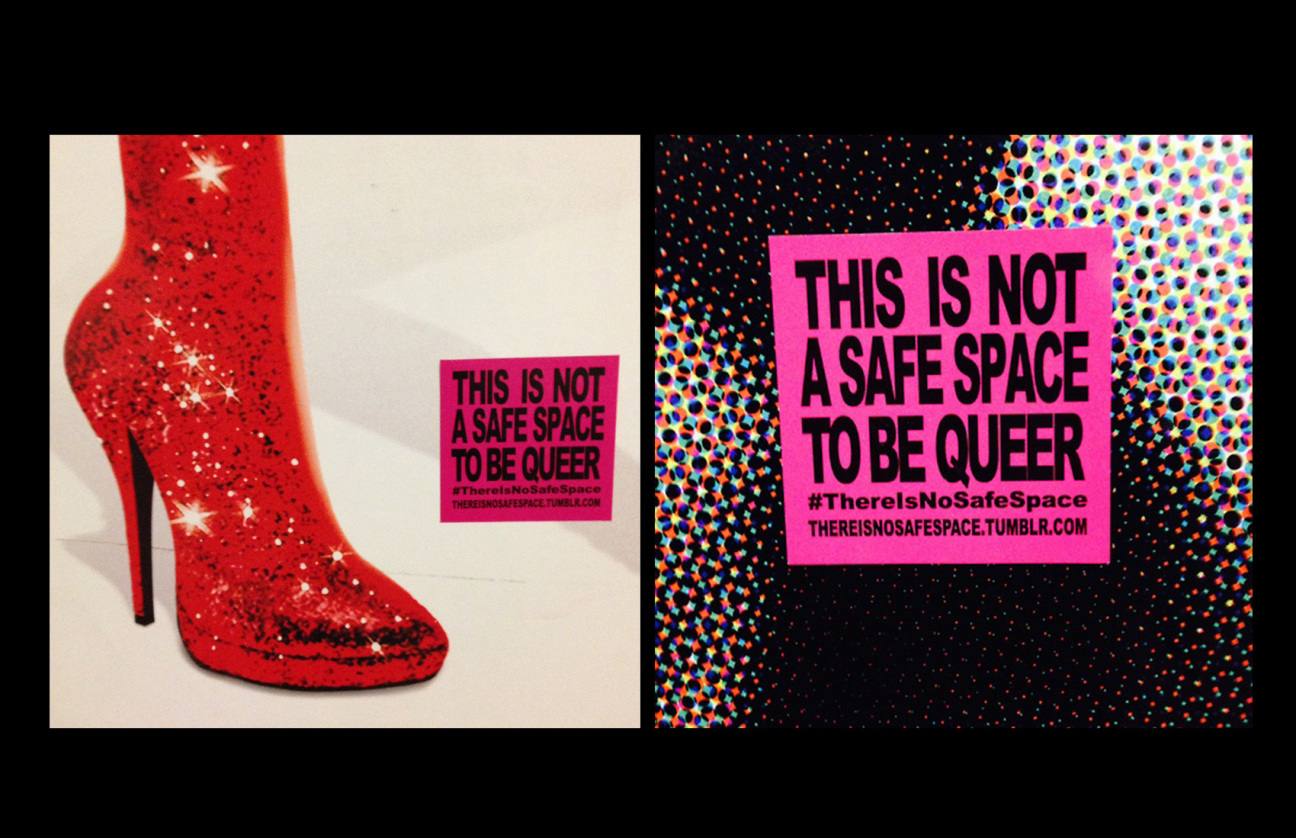

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

New York-based performer, actor, and musician Nashom Wooden, aka Mona Foot. Decades before RuPaul started Drag Race, Wooden created and hosted "Mona Foot’s Star Search,” a weekly drag queen competition that was hilarious and wild. He also starred alongside Philip Seymour Hoffman in the movie Flawless, 1999, which inspired a Y2K era club hit of the same name, performed by Wooden music trio The Ones. Sadly, he was one of the first high-profile queer artists to succumb to COVID-19 in 2020.

How did you encounter Wooden’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

I first saw Wooden perform as Mona Foot when I moved from San Francisco to New York in the mid-'90s, a time in my life when I was going out seven nights a week to queer bars in the city. I think “Star Search” started at The Pyramid before it went to Barracuda, and I remember being amazed by this buff-as-a-bodybuilder, gorgeous Black man performing in heels and wigs.

He was a great lip-syncer, and he was so funny and dry on the mic as the host of “Star Search.” I’ve always had a deep appreciation for the way that queens keep it real through lacerating comments that keep everybody in check. Wooden was very adept at doing this in a manner that was somehow relaxed and also quick-witted.

How has his work shaped yours?

I think all contemporary queer artists working with performance owe an enormous debt to the courage, cunning, invention, and ferocity of drag artists, who have been lampooning and creating culture—brilliantly, and in equal measure—forever. Wooden's gambit of being a muscle-bunny-cum-drag-queen showed me how to mix the codes of gender and race and shape them to your liking in ways that were seemingly simple, but unpretentiously complex.

Jim Isermann

The Wisconsin-born, California-based artist mines the domestic design universe’s campiness to create playful and meticulous geometrical compositions.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

Scott Burton, an openly gay artist who entered the art world through playwriting and the New York experimental theater scene of the 1970s. He is most well known for his site-specific commissions, including at Battery Park and the Equitable Center. His life was cut short by complications of AIDS.

How did you encounter Burton’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

In 1979, when I was a grad student at CalArts, the powers that be scheduled me for a studio visit with Scott Burton. At the last minute, Burton canceled his trip. I didn't even know his name, but the missed visit piqued my curiosity. Without Google, my research took shape through library books, galleries, and museum collections. In 1989, I happened upon Burton’s legendary Brancusi MoMA exhibition curated from their permanent collection in which he prioritized the unique pedestals. For possibly the first time ever, a rough-hewn stack of forms was exhibited as a sculpture in its own right—without the mirror-polished, impenetrable object atop it.

How has his work shaped yours?

Scott Burton gave this boy from the Midwest permission to embrace my obsession with architecture and interior design, to make unashamedly queer work. Like Burton, use became integral to my sculptural work—ever since my “Flower” exhibition in 1986 when seating and lighting sculptures functioned as gallery fixtures. For the last 20 years, I have taught Scott Burton’s canny quotation of the vernacular and historical, his ability to simultaneously communicate to both the queer cognoscenti and the general populace. This is exactly where I want my work to live.

Kan Seidel

The Omaha-born, New York-based artist, writer, and activist makes poignantly humorous paintings and sculptures that unravel and explore familial expectations, configurations, and motivations.

Who is a queer artist who came before you who you think more people should know about?

The queer artist who most impacted me at a young age and who I think should be better known for spearheading queer representation, despite not actually being gay herself, is the writer Ursula K. Le Guin. In her futuristic expanded universe, she introduced queer societies and truly non-binary humans who could alternate between fathering a child or getting pregnant, the singular they before it was trendy, a very LGBT-integrated sort of feminism, and romanticized homosexual monogamy. She examined these far-out worlds through the lens of scientific "observers," making them feel more legitimate and possible, which transformed the landscape of my closeted teenage mind.

How did you encounter Le Guin’s work? Why were you drawn to it?

I first found The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969, on a trip with my mom to the public library. I had finished and loved the Dune books, and I wanted another sci-fi universe to explore. I had no idea what was in store, but when I met that first completely androgynous character and those first gay relationships depicted as unmentionably mundane, I was hooked.

How has her work shaped yours?

I love playing with the human form in ways that call into question gender and the use/usability of different parts and appendages, creating androgynous, intersex, polymorphic, and monstrous but lovable characters. Le Guin's fully normalized but unprecedented depictions of this kind of variability were a springboard for that sense of limitlessness in my imagination around bodies.

in your life?

in your life?