taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith. Image courtesy of supremecourt.gov.

Even from beyond the grave, Andy Warhol is pushing the world to question the bounds of creativity and commercialization. Last Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Andy Warhol Foundation in a case levied by photographer Lynn Goldsmith over Warhol’s use of her photograph to create a silk-screened portrait of the music legend Prince. The court determined that Goldsmith should have received a licensing fee when Warhol's work, based on her photograph, was reprinted in Vanity Fair.

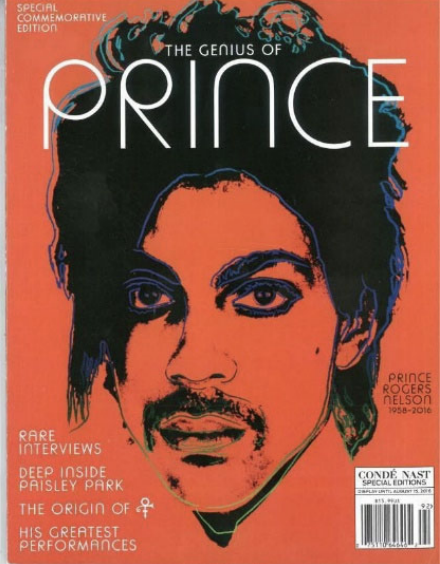

of a special edition magazine published in 2016 by Condé Nast. Image courtesy of supremecourt.gov.

The implications of the ruling for the future of so-called "appropriation art"—art based on borrowing existing text or images—is subject to debate. But what is clear is that Warhol remains one of the few artists who is as controversial in death as he was in life. Warhol came up against searing reviews over the course of his entire career. As the art world mulls the significance of the court's decision, we are taking a look back at some of Andy's worst reviews—which double as a handy guide to his rabble-rousing art practice.

Warhol's divisiveness was clear from his first-ever solo show at New York’s Hugo Gallery in 1952, where he displayed his series “Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote.” Critic James Fitzsimmons wrote that it had “an air of carefully studied perversity.” The Capote-focused exhibition took place long before the artist and writer formed a friendship, or even an acquaintanceship. Warhol’s fascination with Capote teetered between obsession and inspiration, as the artist was known to stalk the author. “When he came to New York, he used to stand outside my house, just stand out there all day waiting for me to come out,” Capote revealed in Gary Comenas’s oral history of Warhol.

Warhol was fascinated by consumer culture, famously painting and mass producing prints of Campbell’s soup cans. “The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonald’s. Peking and Moscow don’t have anything beautiful yet,” the artist once said. He began using a silkscreening technique to reproduce famous images in the early 1960s as other artists like Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg also began to engage with symbols of popular culture.

In December 1962, the debate within the art world became so intense that New York City's Museum of Modern Art convened a symposium to air it out. Some audience members claimed Warhol and his peers had “capitulated” to consumerism. Others applauded the frank engagement with American culture.

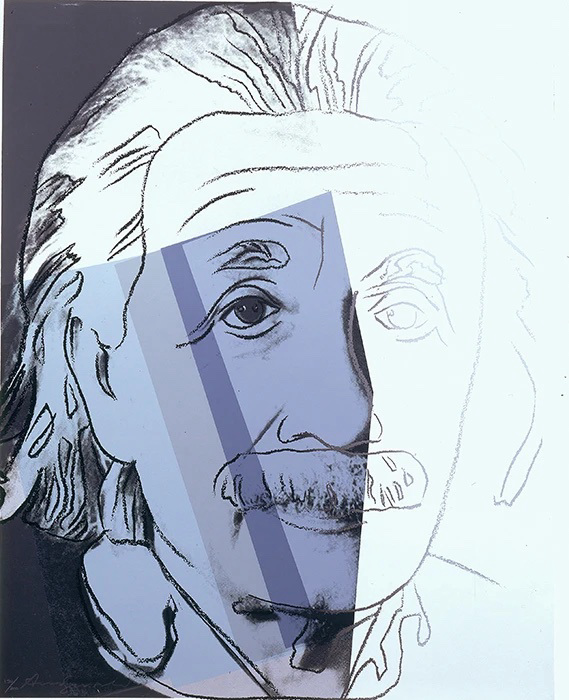

Later, in the 1970s, Warhol’s fascination with celebrity became increasingly embedded in his work. He began creating silkscreen portraits of famous figures including John Lennon, Diana Ross, and Brigitte Bardot. Some critics dismissed the series as superficial and commerical, lacking depth and nuance. A decade later, Warhol's collaboration with the ascendant painter Jean-Michel Basquiat on a series of paintings attracted the ire of New York Times art critic Vivien Raynor. “Here and now, the collaboration looks like one of Warhol’s manipulations, which increasingly seem based on the Mencken theory about nobody going broke underestimating the public’s intelligence," she wrote. "Basquiat, meanwhile, comes across as the all too willing accessory.”

Warhol—who died at 58 in 1987—was all too aware of the pourousness between his depictions of consumerism and his implication in it. He admitted that his exhibition “Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century,” staged at Manhattan's Jewish Museum in the 1980s, was little more than a market ploy. In his diary, he wrote, “They’re going to sell.” Among the harshest reviews came from New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer, who stated that "the show is vulgar, it reeks of commercialism, and its contribution to art is nil." He added: "The way it exploits its Jewish subjects without showing the slightest grasp of their significance is offensive—or would be, anyway, if the artist had not already treated so many non-Jewish subjects in the same tawdry manner."

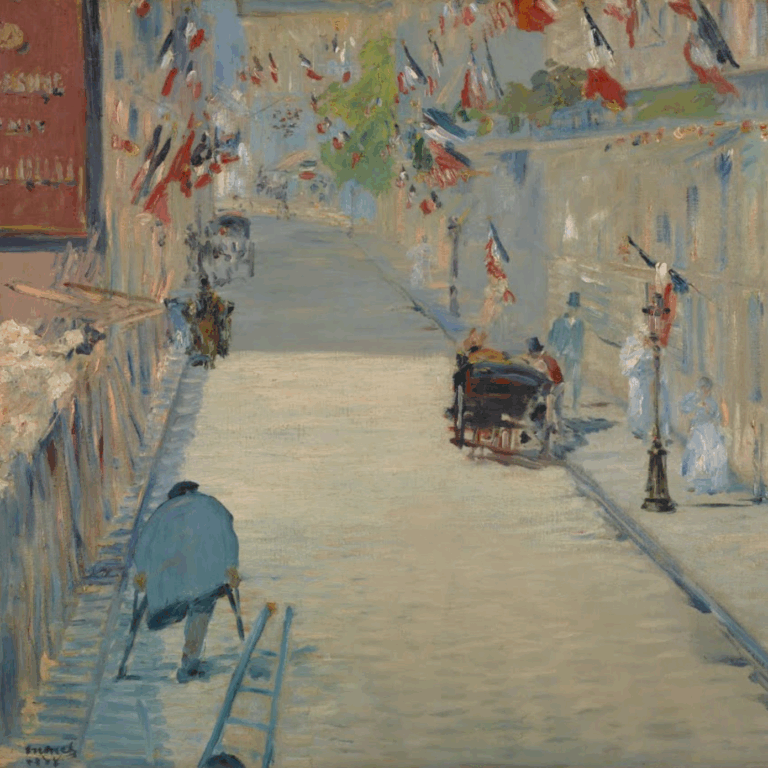

Warhol's critics have done little to diminish his market or influence. Some of the works that drew negative reviews are on view now, including his collaborations with Basquiat at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris (through August 28). In New York, the Brant Foundation is presenting a survey of Warhol's four-decade career (through July 30). Go see it for yourself and levy your own verdict.

in your life?

in your life?