This past Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court finally heard oral arguments in photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s lawsuit against the Andy Warhol Foundation over the late artist’s use of her 1981 photograph of the musician Prince in a series of screenprints released in 1984. Far from a petty spat between two creatives, the case’s results will have far reaching implications beyond the art world. Simply put, the future of creative freedom and copyright laws are on the docket.

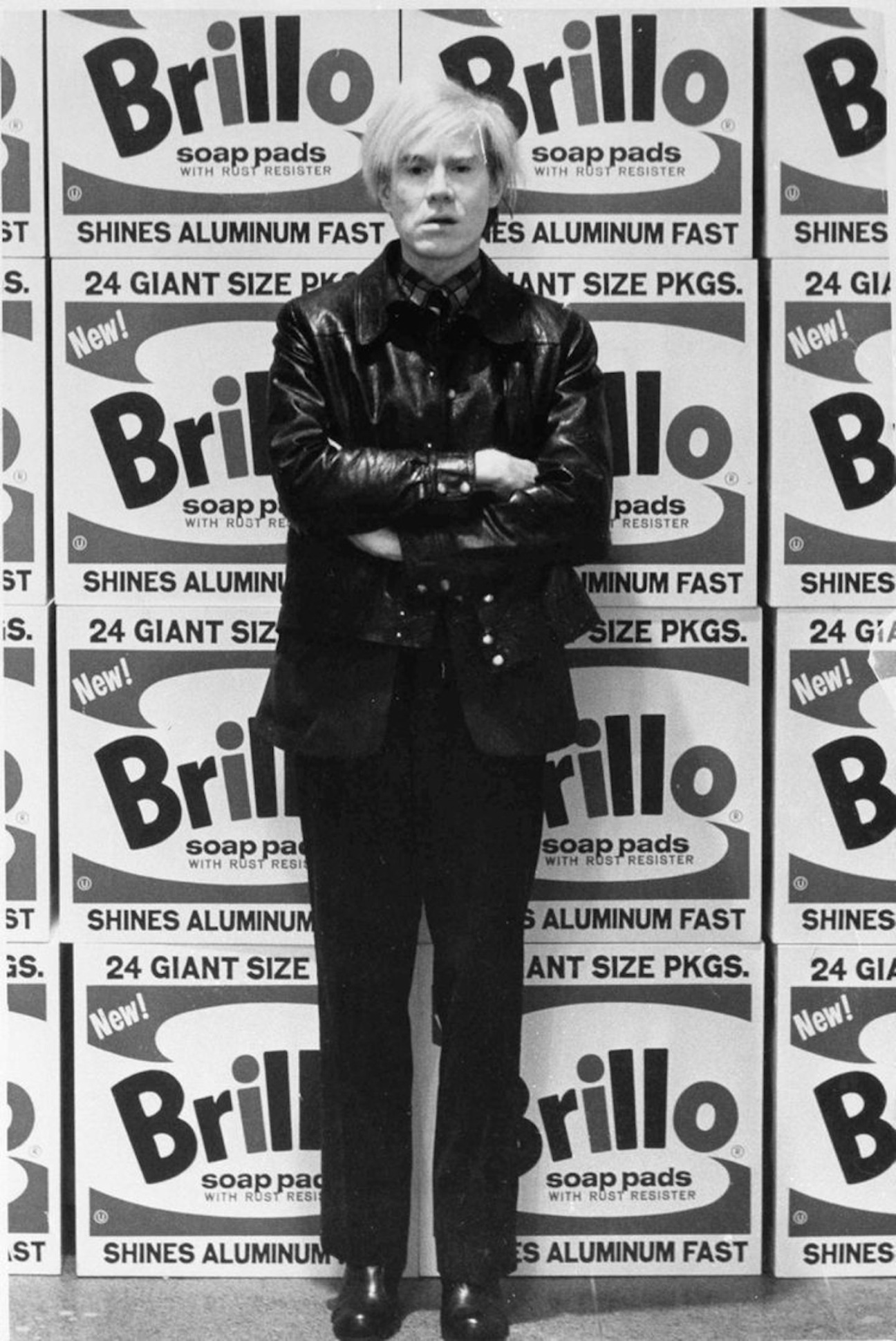

Pinterest.

The dispute began in 2017, when Goldsmith was made aware of Warhol’s Orange Prince print on the cover of Vanity Fair’s issue honoring the recently-deceased artist. In 1984, the magazine had initially paid her $400 to license the portrait to create the Warhol illustration. However, in the new 2017 publication, Goldsmith was neither credited as the photographer, nor paid for the image’s use. The Warhol Foundation, on the other hand, charged the magazine $10,000 for the image. She then contacted the foundation, which responded with a preemptive lawsuit requesting that the court declare Warhol’s portrait fair use. Goldsmith fired back with a lawsuit of her own.

Roman Martinez of the firm Latham and Watkins, which is representing the Warhol Foundation, argued that Warhol, through his print-making process, transformed both the intention and appearance of Goldsmith’s original image, thus imbuing it with a completely new meaning. According to the factors used to determine fair use under the Copyright Act, this would render Warhol’s use of the image valid.

Instagram.

Martinez contended that a ruling in favor of Goldsmith could “have dramatic spillover consequences not just for the Prince series, but for all sorts of works of modern art that incorporate preexisting images and use preexisting images as raw material in generating completely new creative expression by follow-on artists.”

With regard to Goldsmith’s position, her lawyer, Lisa Schiavo Blatt of Williams and Connolly, responded by arguing that, if a ruling for the Warhol Foundation were to prevail, “copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats,” and that it would then be possible for anyone to create an unlicensed spinoff or sequel to an existing work.

Simply put, the question being considered by the Supreme Court is whether or not changing the source material’s meaning makes a work transformative, and thus in-accordance with fair use policies. The decision of the case, however, will have broad ramifications, and several artists and legal scholars have already weighed in to give their opinions. Among them are artist Barbara Kruger and curator Robert Storr, who jointly filed an amicus curiae brief on behalf of the Warhol Foundation, in which they postulate that it has always been common practice among artists to copy and reference one another’s work.

In essence, the duo contend that a tightening of the fair-use doctrine would have an adverse effect on creativity, as artists may become fearful of costly litigation and cease using copyrighted work. This would, in their view, severely restrict cultural exchange and discourse.

The Court is expected to reach and release its ruling sometime in the coming months. In the meantime, scholars, artists, and legal experts from all sectors of the art works will no doubt be waiting in great anticipation, and continuing to debate and mull over the consequences of the case.

in your life?

in your life?