The smallest of the Frieze franchises is New York, where 60 participating galleries set up shop inside The Shed in Hudson Yards. The fair’s 11th edition, which opened to VIPs on Wednesday and runs through Sunday, May 21, is a tightly edited affair—perhaps surprisingly, given that it takes place in the global art market’s capital. Also snug? The aisles during the VIP preview. A crowd of well-heeled collectors and advisors jostled through the booths as they pointed and named their reserves. No New York Art Week fatigue here.

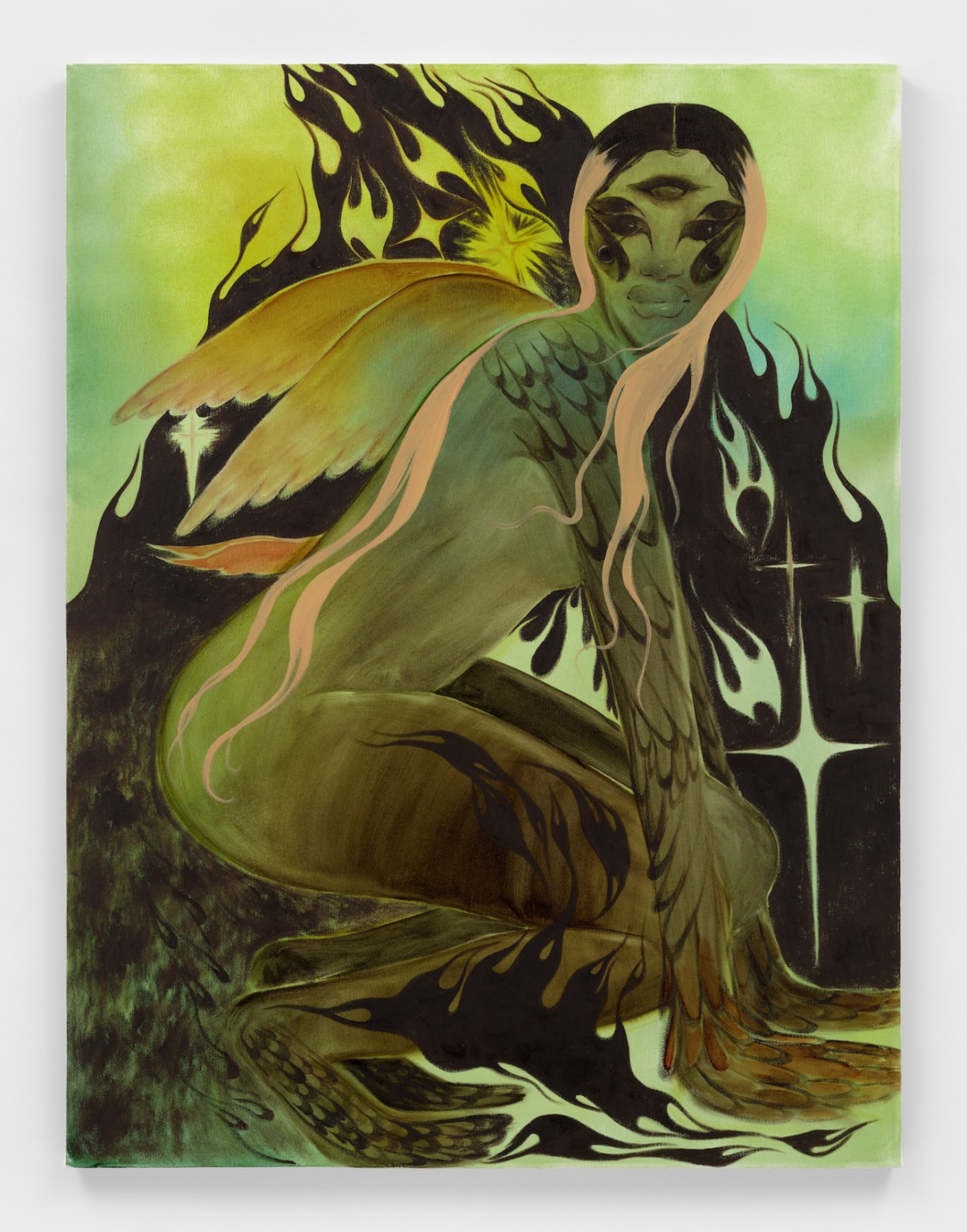

Sprinkled across The Shed’s eight floors are works from in-demand young guns, like Lauren Halsey at David Kordansky (all sold), Naudline Pierre at James Cohan (all sold, topping out at $130,000), and Ilana Savdie at White Cube (one sold for $45,000), as well as the latest wave of older artists receiving delayed recognition, like Mary Lovelace O’Neal at Jenkins Johnson (priced at just under $1 million) and Pacita Abad at Tina Kim (Irawan went for around $300,000 to a private collection).

By the evening hours, sales were well underway. Were they skyrockets in flight? For some artists, yes—like Nan Goldin at Gagosian (more on that below). But some market jitters were evident as even big-ticket names at top-tier operations remained conspicuously available despite the growing tendancy to pre-sell before the doors open.

As usual, Americans represented the lion’s share of buyers, and $25,000 to $100,000 was a sweet spot for sales. But perhaps the most valuable takeaway from a fair like Frieze is an indication of where the conversation is headed.

The works on view suggest that collectors have woken up to the fact that the 1960s and ‘70s had more going on than just Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Carl Andre. And while New York is and remains a painting town, dealers seem to be developing new ways to market interventions, sculpture, and other less wall-friendly work. To offer a snapshot of different parts of the market, we pulled together six of the most interesting works on offer and explored what they tell us about where the art world is going next.

Hauser & Wirth

Jack Whitten

The Apollonian Sword, 2014

$3 million

The most expensive work at the fair we could find, The Apollonian Sword (2014) is also among the largest: a six-foot-tall marble sheath with a mulberry wood base. Whitten is an icon of American art, yet he remains better known for his technical experimentations with paint than for his boundary-pushing sculpture. (Interestingly, the artist himself once said, “Without a doubt, the sculpture has had more influence on my painting than anything else.”) Whitten’s sculpture gained overdue recognition in a dedicated 2018 survey at the Met Breuer, but it is still a relatively rare sight outside the institutional context. Fittingly, this work is currently on hold for a museum, according to the gallery.

Thaddaeus Ropac

Martha Jungwirth

Ohne Titel, 2020

€425,000

"Have you seen the Martha Jungwirth at Ropac?" That question was posed to us at least three times during the VIP preview. And yes, indeed, we did. Jungwirth's eight-foot Ohne Titel, a chorus of rigorously worked pink paint that draws on primordial instinct and memory, anchored Ropac's booth and made macho Georg Baselitz almost look like a shrinking violet. Now 83, Jungwirth is finally commanding the prices that match her influence in the 1960s Austrian painting scene, and her two works (the other priced at €280,000) were among the first to sell out of the booth. Ropac has presented a solo show of Jungwirth every year since the gallery started representing her in 2021, including a current presentation in Seoul (open until June 10). In another testament to her global appeal, the large work at Frieze was snapped up by a Chinese collector. These days, as the demand for the hot and young starts to cool, it seems momentum has shifted to a reliable store of value: older, overlooked women.

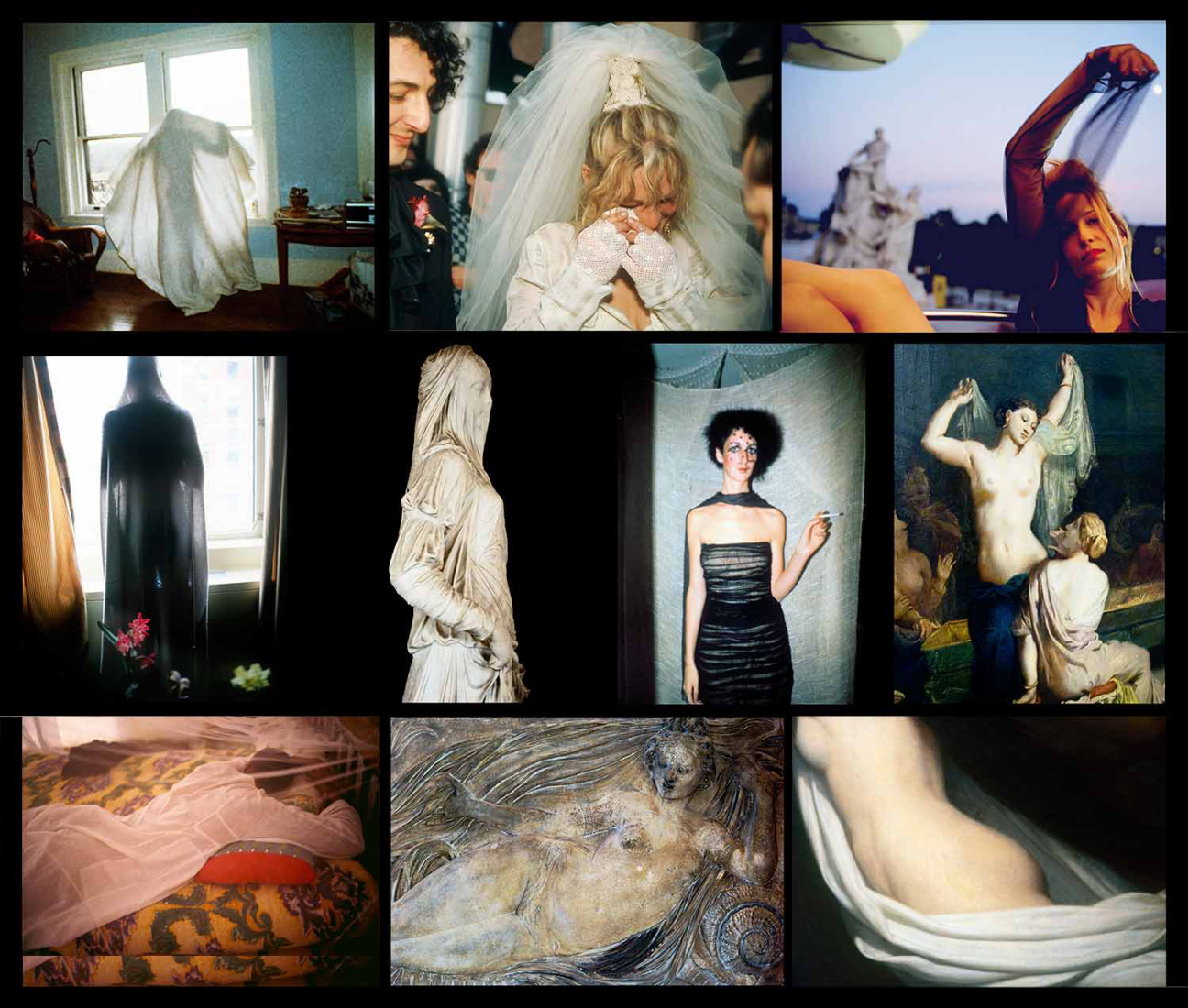

Gagosian

Nan Goldin

Veiled, 2011-14

$60,000-90,000

No one would dare call Nan Goldin overlooked, particularly after the years she spent publicly crusading against the Sacklers. Her Ballad of Sexual Dependency remains the defining American photographic series of the 1980s, and firmly placed Goldin in the pantheon of New York artists. Her market, however? Doesn’t match the CV.

Earlier this year, Goldin made waves when she announced plans to join Gagosian, and the gallery dedicated its Frieze booth to eight of her “Grid” works. A highlight is her “Scopophilia” series, originally commissioned by the Musée du Louvre, which pairs archival, autobiographical images with paintings and sculptures from the museum's collection. Over the past decade, a single Goldin photograph has routinely sold for around $10,000 while some have gone as high as $30,000. Now, with this (mostly sold-out) booth, the prices have seen hockey-stick growth. Goldin is already a star—but soon, she’ll have the bank account to match.

Silverlens

Carlos Villa

Kite God Coat, 1979

$400,000

Kite God Coat would never be confused for Minimalism—though Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa came up in the sculpture scene of ‘60s New York. Villa, who died in 2013, then returned to his hometown of San Francisco, tucked into the teachings of the Third World Liberation movement, and began utilizing his body as a medium to create prints, casts, and assemblages. Institutions have long acquired his work and curators stress his importance, but he is not yet a household name. Kite God Coat—made from rooster and pheasant tail feathers and paper pulp—is one of Villa’s “Cloak” objects, which he donned during performances. It remains one of two examples—out of 15 in existence—still in private hands. The rest were either lost to history or destroyed by Villa himself.

Kurimanzutto

Minerva Cuevas

Sunset with birds, 2022

$25,000

An oil on canvas as a protest to Big Oil? Minerva Cuevas, the socially engaged conceptual artist, isn’t happy about American oil companies drilling off the coast of Indigenous lands in her native Mexico. In fact, Big Oil is her primary subject. For this series, Cuevas reclaimed found oil landscape paintings and dipped the lower edges in chapopote (tar, in English), making the trickling tar harden as it falls off the canvas. Paisaje Marino, 2022, was snapped up moments before the fair opened, so Kurimanzutto hung Sunset with Birds in its place. Cuevas is best known for large-scale installations and interventions, making these paintings a rare opportunity for a collector to bring her work home.

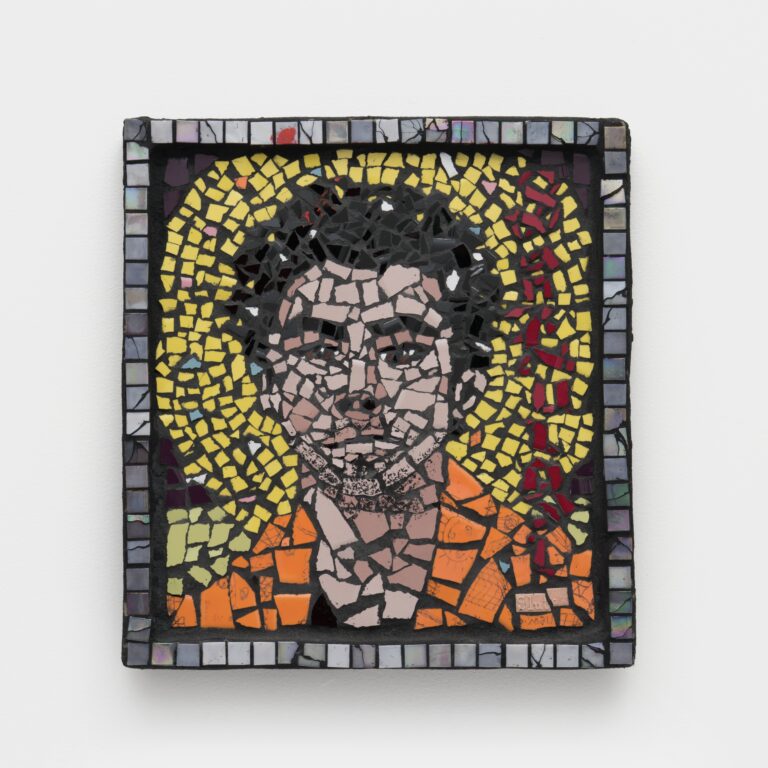

Daniel Faria Gallery

June Clark

Lift Ev'ry Voice (from the Perseverance Suite), 2021

$14,000

Born in Harlem in 1941, June Clark ditched the United States for Canada in her late 20s, seeking a reprieve from America’s political landscape. While she started out as a photographer, she embraced assemblage to explore Black identity and African American heritage through objects. Daniel Faria’s presentation marks the first time Clark is showing in New York since her 1997 residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she made her most famous work, Harlem Quilt (which, incidentally, Faria brought to Art Basel Miami Beach in 2021). Now 82, Clark is continuing to create. Her recent “Perseverance Suite” series, on view at Frieze (with Lift Ev'ry Voice still available by press time), are assemblages made of tools, like shovels and hoes, that her ancestors were forced to use, now rendered futile and transformed into sculptural objects. In the words of the artist, “I exist because of those who have come before me; those who persisted and persevered.” Now, Clark says, “My ancestors can watch and rest.”

in your life?

in your life?