“The past is so present in my days,” says Emma Cline from her sun-filled Los Angeles home. “I’m always circling back to things that have happened, and there's never that clear storybook catharsis that I'm looking for.” The writer, whose breakout 2016 novel The Girls positioned her as a literary darling and an arbiter of a new brand of dark, eerie feminism, followed up her debut with Daddy, a short story collection that probes the frailty of human connection. Yesterday, the Sonoma, California-born author released The Guest, a smoldering summer nail-biter about a young grifter and sex worker, Alex, who is expelled from the lush, manicured finery of the Hamptons summer set when her well-heeled older companion moves on.

Adrift with little money, some pilfered prescription pills, and her financial and psychological wellbeing in jeopardy, Alex spends a hazy week out East—shapeshifting blithely from fratty weekend partier to urbane insider as needed to secure a bed for the night or a seat by the pool—biding her time until the Labor Day party that she’s convinced will restore her ruptured relationship. Cline chose to bracket the novel firmly in the present, offering no origin story for her reckless protagonist, who drifts from mark to mark in a mental fog, rootless. The Guest conjures a faintly seasick aftertaste that lingers through its dark climax and beyond its final pages, ensuring its status as one of the summer’s marquee novels. Here, Cline talks to CULTURED about The Guest, shark-infested waters, and resisting the neatness of narrative.

CULTURED: Was there a single moment or experience that sparked The Guest?

Emma Cline: There was an image in my mind. It didn’t happen to me or anyone I know—it's one of those weird dream images that just lodges in your mind. A young woman is floating out in the ocean. She has the sense that there are people waiting for her on shore, and that when she finally comes in, it’s going to be bad. She's backed herself into some sort of a corner, and thinks to herself, I can't go back in, but I can't keep treading water out here either. There’s something about that image—the emotional temperature of it—that made me say, “I want to write about this character.”

CULTURED: The California coast plays a big role in a lot of your writing. The Guest is set in the Hamptons—another place defined by its beaches, but a new setting for you. What is it about these seaside geographies that are so captivating to you, and what compelled you to set the book on Long Island?

Cline: I’m from Northern California, where the beach culture is so different from the East Coast. Our beaches are freezing cold, and rocky, and the waters are shark-infested. They're very beautiful, but they're not the most welcoming landscape to the human. When I went to the East Coast for the first time in my early twenties and spent time out East with friends, I was so surprised by the landscape.

CULTURED: How so?

Cline: The beaches there are so mild, and the water is so warm. There's something almost surreal about the gentleness of the landscape and the light. I was also fascinated by the summer community that forms there, which seems to replicate the class and power dynamics of the city but in this smaller universe. It seemed like an interesting setting for a character who is out of sync with the world around her.

CULTURED: What did the research process for the novel look like?

Cline: I started the first draft in 2016, before The Girls came out. I was mostly working on short stories then, and I would return to The Guest from time to time, but not in a super focused way. In late 2019, I picked it up again for a few years. For research, I really just went to the beach. So much of what I'm after in my writing is conjuring an atmosphere or mood, so I really try to put myself in situations and—I’m trying to think of a better term than “soak them up…” I would visit my friend out East and ask myself things like, What is the color of the sea right now? Why do these dunes look so peculiar to my eye?

CULTURED: Were there particular thematic elements that you wanted to clash against each other when you were plotting out The Guest?

Cline: I was thinking a lot about how, at least in my experience out East, many communities aren't very welcoming to outsiders. Even to go to the beach you need a residential parking permit. People aren't really going on day trips out there. Everything is organized in a way that keeps out people who “don't belong.” I thought, What would it look like to be character in that space who really doesn't belong? How could they get themselves from day to day, surviving in a place like that?

CULTURED: Alex, the protagonist, is a perpetual outsider in this place, but she’s also conning the insiders of this community and living off of its excess. This is part of what makes the novel so tense. What do you think about the broader fascination with con artists—and, separately, sex workers—in our culture right now?

Cline: I have a hard time speaking to what the larger interest in con artists might be, but speaking for myself as a reader and writer, it's very fun to watch people be good at something. In this case, Alex is good at manipulating the people around her. I also thought a lot about Patricia Highsmith and The Talented Mr. Ripley specifically—why is it so fun for us, as readers, to watch this person do bad things? How does Highsmith make it so we want him to get away with murder? She put us in a mindset where everything this character does feels inevitable.

As for sex work, historically in a literary context, there's a tone of cleverness and villainy used to characterize a woman who gets by this way. That presentation has changed a lot over the last 10 or so years, thanks to voices in literature and in the culture that are increasingly embraced. But I’m very careful as a writer to avoid situating my characters within a dialogue—as a writer, the most helpful thing for me is to be like, “This specific character is having a very specific experience, and it doesn’t have to speak to anything larger.”

CULTURED: Alex is an unsettling character in her disregard for her own safety and her ability to transform herself into whatever the situation requires—she morphs from sex worker to fratty weekend partier, from well-heeled arm candy to reckless seductress. What was your approach to fleshing out this character?

Cline: I was interested in questions of female agency. Often, we want the narrative to be that women gain power through subjecthood. But it's a little more uncomfortable when a character like Alex gains power by objectifying herself. For Alex, there is real, tangible power in turning herself into an object. Her sex work literalizes this transactional dynamic, which is the lens through which she sees the world. It’s also particularly prevalent in this Hamptons ecosystem she’s passing through—certainly between women and men, but also between parents and children, employers and employees, and so on. Everyone is playing some kind of role in a transactional relationship.

CULTURED: Her relationship to sex runs, in some ways, counter to a lot of today’s rhetoric around sex positivity. Alex’s relationship to sex is dissociative—she’s distant from her own sex life and the choices she makes.

Cline: Completely. When I was trying to think of titles for The Guest, I thought about the words that circled around this book for me, and one of them was "disassociation." I was really trying to portray a character who is so perceptive of the world around her—to the point where she can manipulate people and maneuver through it. But at the same time, she lacks a connection to her core self and is alienated from her body. I was interested in that strange balance between seeing a lot and moving through the world like a ghost.

CULTURED: The novel’s whole plot is powered by one central delusion—Alex thinks that, if she can just get by long enough to make it to a Labor Day party at the end of the week, her financial and psychological stability will be restored. For someone with such a cynical view of relationships, this is an interesting blindspot for Alex. How did you approach that?

Cline: I'm drawn to characters who are deluded in some way. Most people are a little deluded. That's just how you get through the bizarre experience of being a human—you have to create a story that casts you as the hero. As a culture, we engage in acts of self-narrativization and self-delusion all the time.

CULTURED: In The Girls, there’s a dual chronology—the characters look back at their lives from the present day in order to understand their current experiences. The Guest takes a very different approach, in that you really resist giving the reader any of Alex’s backstory. There’s no past experience to empathize with, which makes her a very cold protagonist. Was this a deliberate choice?

Cline: I’ve talked to a lot of my writer friends about this. After you’ve written one book, the next book often feels like a reaction to it. The Girls took place over many decades and was very much about how the past informs the present, and I knew I’d be spending years on whatever I wrote next. I was like, “All right, let’s do something in the opposite direction, in a very controlled world, with a very controlled timeline.” I made the narrative choice for Alex not to have a backstory because I wanted to resist the expectation that a character’s behavior can be rationalized by their past. That lack of backstory also mimics the way she moves through life—she's not somebody who allows the things that she’s done—or that have been done to her—to really settle inside her.

CULTURED: It makes it hard to situate Alex within a victimhood narrative, which is something we’re trained to look for. So much of what you've written resists that kind of narrative—is that something that you’re intentional about?

Cline: I think you're totally right. If I look at my work, I am resisting that, but it's not a thing that I'm super conscious or careful about as I'm writing. I'm not thinking about how it’s going to be read, but, as a reader, I know that I don't seek out books where the moral lines are really clearly drawn or where I feel like I’m being educated.

CULTURED: I know it’s annoying to talk about endings, but I can’t resist. What, to you, makes the perfect ending?

Cline: More and more, I find myself rejecting the neatness of narrative, and the idea that stories have a beginning, middle, and end. I’m realizing that people don’t experience life that way. At least for me, the past is so present in my days. I’m always circling back to things that have happened, and there's never that clear storybook catharsis that I'm looking for. Especially with short stories and this novel, I'm kind of interested in creating a narrative that is still artful, that still has a considered shape, but that resists a neat ending. Like, after the dismount, what sort of what feeling do I want the reader to be left with?

CULTURED: And how did you answer that question with regard to The Guest?

Cline: I think I want to create a tone that’s unsettled, otherworldly, and adrift.

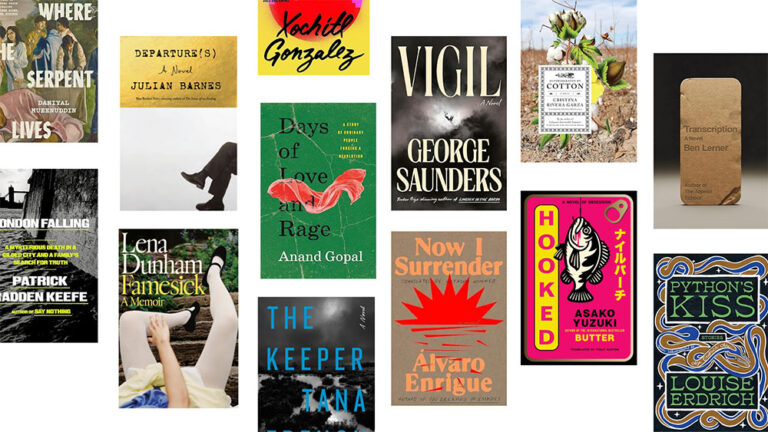

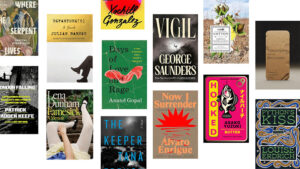

CULTURED: What were the books or films that kept you company while you were writing?

Cline: There's this short story by John Cheever called “The Swimmer” that I was thinking about a lot. I mean, they're about such different people—”The Swimmer” is about a middle aged drunk in midcentury Connecticut. The Guest is about a contemporary 22-year-old woman. But I have such a strong emotional memory of that story—its ending is so discombobulating and forlorn, and there's something really horrific about it to me.

CULTURED: How do you balance living and writing?

Cline: When I’m in the depths of a book, I’m really in it. I see no one. But when I’m in between projects, I look for balance. Living life is a really big part of being a creative person of any kind. You need to live life in order to write about it.

in your life?

in your life?