Welcome to “A Night at the Opera,” a bi-monthly column dedicated to demystifying the art form for the Aida-curious and the Ring Cycle-indoctrinated alike. Along the way, you can expect gossip from the champagne line, epiphanies at intermission, and critiques courtesy of CULTURED's Editor-at-Large Kat Herriman, and the magazine’s favorite artists, designers, actors, and writers. In this installment, Herriman is joined by the artist Cynthia Talmadge at The Met Opera's presentation of Der Rosenkavalier for a night of new money, seat thievery, and underground glamour.

In college, my best friend and I used to collect the brochures of the rehab centers we wanted to attend. It got to the point where my friend’s mother told him the family wouldn’t pay for Hazelden no matter how nutted out he got. She understood what it all meant. We didn't want to graduate into jobs; we wanted to retire into bathrobes and long afternoons in the sun with ceramics classes and periodic writing fits thrown in.

I found this youthful desire deliciously preserved in “Leaves of Absence,” Cynthia Talmadge’s first show at New York’s 56 Henry, which featured a to-scale dorm room at McLean Hospital and a back room presenting a calendar of options for a lifetime in rehab: winters at Hazelden, springs at Promises, summers at Sierra Tucson. The 2017 show cost Talmadge a year of her life as she meticulously recreated and photographed the same bedroom in different color schemes in her cell-sized studio: one set, four moods. “Leaves of Absence” comes flying back as we sit together in the dark watching Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier at the Met Opera.

Robert Carsen’s production of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier at the Met Opera takes the groundbreaking comedy’s original setting, an idealized reimagination of Vienna in the 1700s, and moves it up to the opera’s birth, the turn of the 19th century. It is a move to center and acknowledge our complicated relationship to the once banned German composer who we know goes on to become a reluctant but prominent Nazi as the president of Hitler’s Reichsmusikkammer. In Carsen’s version, the set consists of two intersecting walls transformed over the course of the performance to become a royal bedroom, an arms dealer’s ballroom, and a brothel. The minimalist staging reveals the ways in which these seemingly disparate places serve many of the same purposes as spaces for negotiating power and class—sometimes with sex, other times with force, often with both.

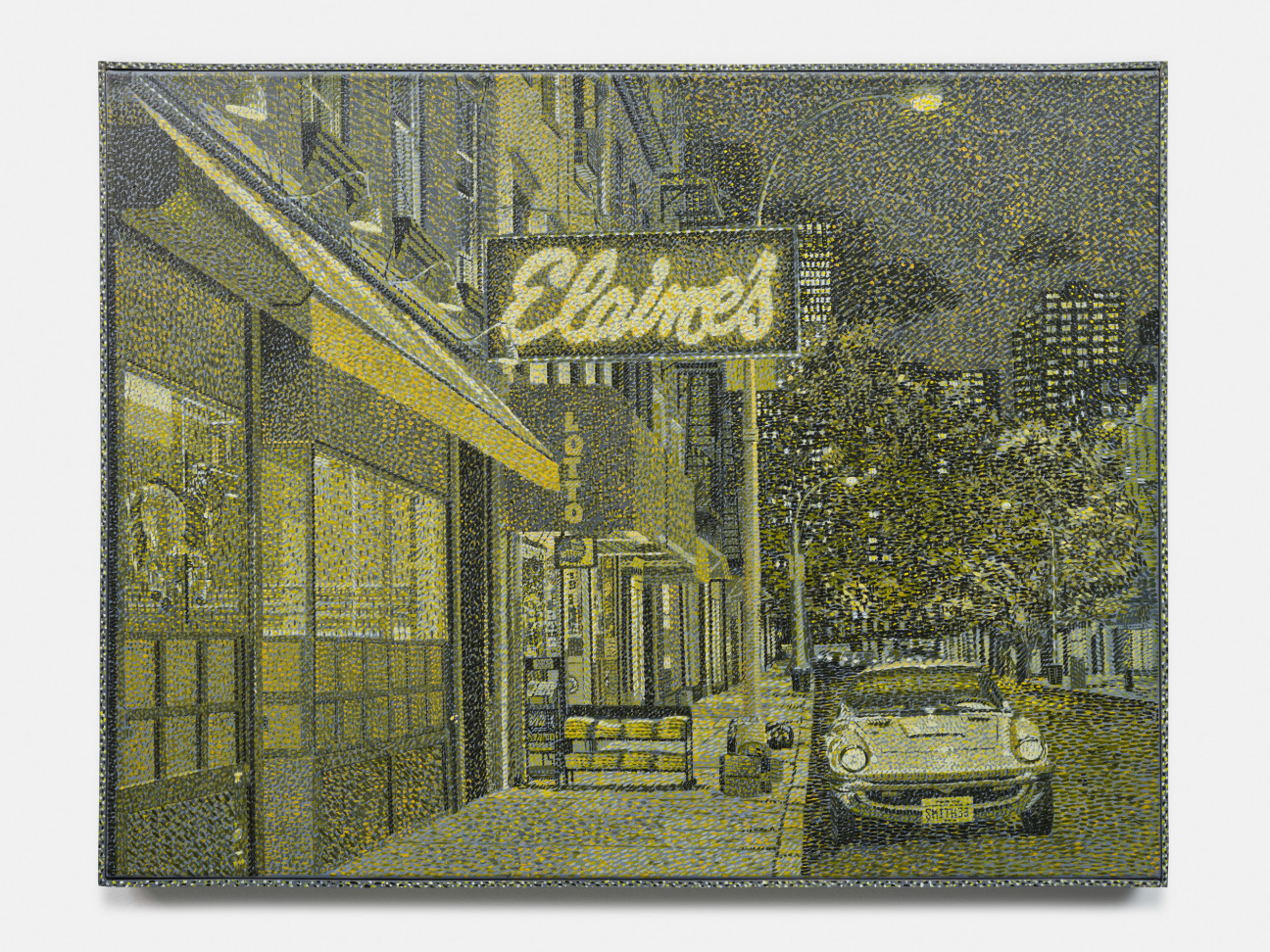

Archiving and decoding the domestic realms fetishized and frequented by the bourgeoisie is preoccupation of Talmadge’s. Like Strauss’s opera, her work as a painter, photographer, and installation artist brings together anachronistic truths, creating powerful collages that reveal something about the past and present simultaneously. Her recent and first show at Bortolami, “Goodbye to All This: Alan Smithee Off Broadway,” is a prime example. Alan Smithee was the universal nom de plume for flailing writers and directors in the 1960s and 1970s. In Talmadge's show, the artist imagines Smithee as a real person—“a down-on-his-luck middle-aged baby boomer” who migrates from Los Angeles to New York, settling in the very Tribeca loft where the exhibition takes place.

With her signature sand paintings, Talmadge captures Smithee's cross-country odyssey through a series of roadside shots of the establishments he might frequent along the way in his Maserati: Elaine’s, Chasen’s, the Director’s Guild of America. Almost all of the infamous places featured are now shuttered or demolished. Like the Vienna of Strauss’s opera, the splendor Talmadge depicts arrives extinct, if not entirely made up to begin with. We think of the 1980s as a time of big-haired exuberant success, yet it was a period where things took an irretrievable turn as Hollywood-sized greed became intellectualized and then algorithmically applied to the masses.

Talmadge moonlights as a historian who dares to do her own research and arrive at her own conclusions. She is a pop cultural expert whose knowledge trails off somewhere before 9/11. So when I joke that our conductor for the evening, Simone Young, looks like Lydia Tár from behind, Talmadge confesses, “I really don’t know anything about opera.” This is what I adore about her. The two of us settled in to to spend the rest of the evening with Lydia.

The first act of Der Rosenkavalier, which translates to “Knight of the Rose,” sets up the parameters of this Edith Wharton-esque class comedy. The older princess, Marschallin, frolics in bed with her young lover, Octavian, while her estranged husband is away. They are interrupted by Marschallin’s annoying cousin, Baron Ochs, who arrives at her doorstep to brag about leveraging their royal heritage to marry into new money while simultaneously asking the princess to make the move possible. Marschallin recognizes an opportunity to test her young lover’s fidelity by sending him to the maiden’s house to inform her of the Baron’s nuptial intentions. It is an act of self-sabotage born of an aging woman’s vanity and the boredom of abundance—a first-world problem that we sympathize with only after a 1990s rom-com-worthy shopping montage where a string merchants present the princess with their wares. This was Talmadge’s favorite flourish in an act that she thought dragged a bit.

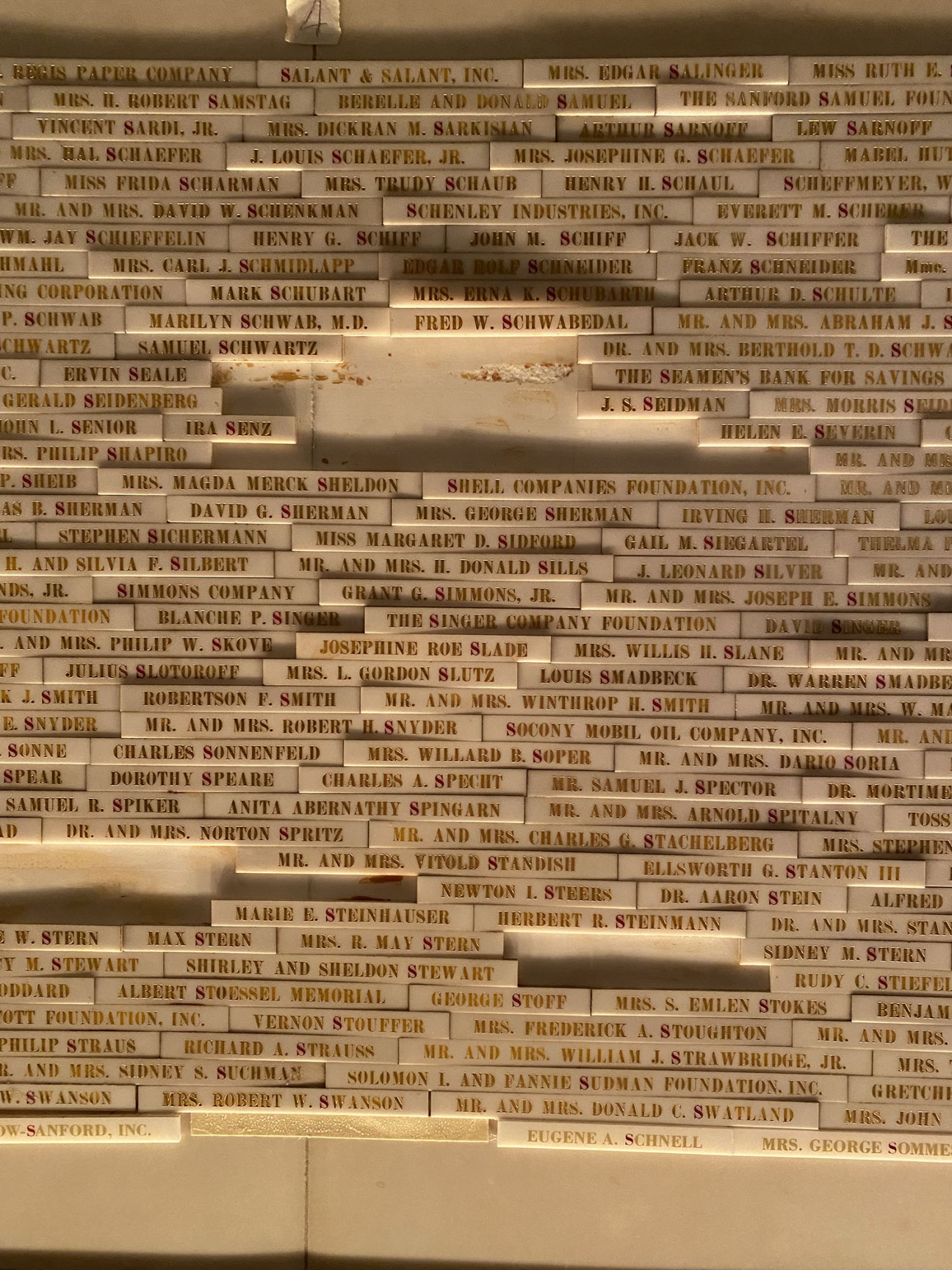

The curtain descends, and so do we to inspect the peeling patrons wall under the whale bones of Wallace Harrison’s opera house. I love this now-defunct VIP bar’s decaying grandeur and have been wanting to show it to Talmadge since the first moment I saw it. (Ditto the built-in ashtrays in the women's bathroom stalls.) Talmadge is a connoisseur of plaques and monuments of all sizes. She made her own two Frieze Londons ago—forging a Henry Moore sculpture inside Carl Kostyál’s Mayfair library replete with a snow machine that flurried suds on top of the permanent collegiate detritus she had affixed to the bronze. We stand in the corner by an Aristide Maillol statue of a reclining woman where we find a plug for Talmadge to charge her phone.

“I like the scene here,” Talmadge says, staring down at the dining room below. “It’s astonishing to think that is one of the last places like this that New York." She doesn’t clarify what kind of places she means, but it's to do with architectural completeness, the Gesamtkunstwerk.

Der Rosenkavalier runs around four and half hours with two intermissions. For its duration—and prior, during the pre-performance aperitivo we had at Shun Lee, Talmadge and I comment on exceptional outfits and accessories on view, like the woman in the peachy sweater set that extends to her pants, or the one carrying what appear to be custom velvet cushions that match the theater’s seats. I tell Talmadge about the underground community of opera-obsessed seat-stealers that I’ve observed who play a comical game of cat and mouse with the ushers. This dance is played out every night—each side attempting to outwit the other before the curtain rises. Talmadge, envisioning the story for my first documentary film, says we should investigate further. There is a conspiracist inside Talmadge that leaps out to surprise you from behind her manicured exteriors, which tonight are smartly decked in Miu Miu brocade and a pastel Prada purse.

Talmadge thinks that Act lll would've landed best if it had ended with a pastel palette. Carsen’s red brothel and its generic Disney-esque prostitute costumes aren’t working for her, even as the backdrop for Octavian’s drag performance. Pastels are a sweet spot for Talmadge who honed her expertise by making preppy Pointillist still lives—a technique she used to create a body of work about Frank E. Campbell funeral home, New York’s starriest place to be embalmed. The obsessive devotion she lavished upon that series was resurrected recently for her first print, out next week with Utopia Editions, which approximates the depth of artistry in one of her paintings through 20 separate screen printed layers.

The morning after the opera, Talmadge texts me: I love how happy the people next to us were. That was the sweetest thing, everyone being so enchanted and happy to be somewhere. The guy next to me gasped and wowed, shaking his head in disbelief when the curtain went up.

I write back: It is a place for believers. A church.

I leave out that it is one of the only ones left for a congregation that still believes in the parables only skyscrapers, martini-tinted evenings, bathroom ashtrays, page six mentions, and a group of world class performers can tell.

in your life?

in your life?