Every Anne Imhof piece is an encounter with raw humanity: flames erupt, and empty fire hoses are proffered. Dogs defecate, and performers check their texts. Though the German artist’s work spans mediums, Imhof is best known for her durational performance works, in which she presides over a gallery hall like an occult puppeteer, harnessing the effects of music, film, architecture, and improvised performance to capture and manipulate the attention of her audience. In 2016, Imhof caught the art world’s attention with Angst, a roving three-part performance that took place at three institutions in Switzerland, Germany, and Canada. In the main gallery at Kunsthalle Basel, a group of vacant-eyed performers—made up of the artist’s friends and collaborators—surrendered their agency to Imhof, acting based on prompts that the artist sent to their phones in real time. In the fog-filled halls of the Hamburger Bahnhof, they wandered under the pacing feet of tight-rope walkers; and at the Biennale de Montréal, they shaved one another’s backs while staring into the eyes of audience members. Shortly after Angst debuted, Imhof was announced as the artist for the German Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, where she presented Faust, a work in which visitors standing on glass slabs watched spontaneous interactions among performers climax and dissipate beneath their feet against a backdrop of empty pill bottles, restraints, and mussed bed sheets.

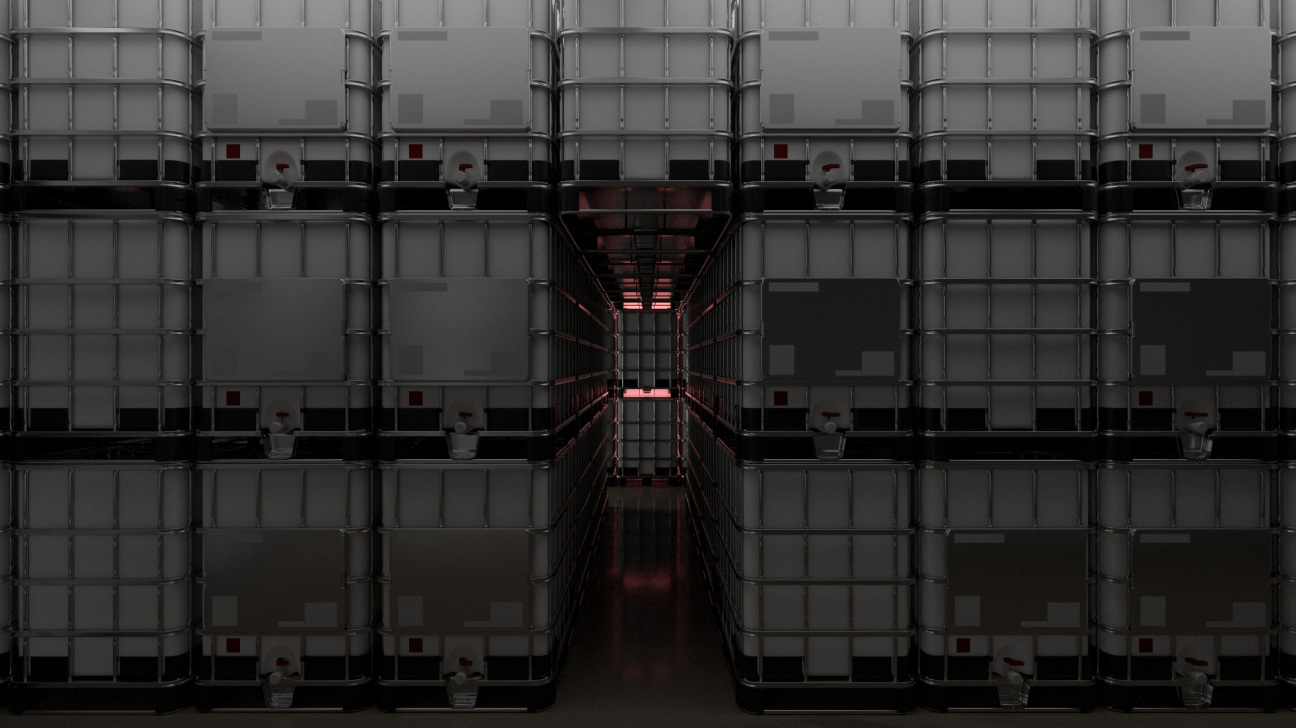

It may be surprising to learn that Imhof, whose works feel deeply rooted in the brutalist built environments of the former Eastern Bloc, feels a kinship with Los Angeles. But today, squinting on a spacious couch in a sun-filled living room up in the canyon, it makes sense. “Honestly, I really love it here,” she says, adjusting the sleeve of her Balenciaga x Adidas soccer jersey, coffee mug in hand. “I think there’s something in Los Angeles that urges artists to use the earth as a place to make art.” She cites Mike Kelley and Chris Burden, two LA-based artists whose strong sense of place has had a powerful influence on her. “The way the outdoors is embraced in artmaking here feels very different from Europe. It’s something that I really enjoy for myself.” Imhof is in town installing her new solo exhibition, aptly titled "EMO," which opens today, Feb. 15, at Sprüth Magers’s Los Angeles outpost. The presentation is Imhof’s first on the west coast, and features a labyrinth of red-lit industrial water tanks (akin to the one she recently exhibited at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum) alongside a series of large-scale figurative paintings featuring common motifs including scary clowns and mushroom clouds, and her two recent video works—Youth and AI Winter—shot in Moscow on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Imhof is a painter first, a practice she returns to regularly while choreographing her operatic live works. In "EMO," she presents a series of paintings based on past performances, snapshots of the instant when a live work detonates: “I go through millions of stills [from past performances] until I find the moment where everything crystallizes,” she says of her efforts to capture the transient effects of her own work. “Performance always creates itself in the now, it can never be held or kept. But painting almost works as documentation of it.”

Critics, awash in the multisensory onslaught of Imhof’s works, tend to single out their gothic, unsettling qualities. How does Imhof feel about that? “I think there’s a certain aggressiveness, a certain coldness that is imposed on the work, and very often this comes from the outside,” she muses. She even appears surprised about the reception some of her projects have received: “Angst was actually a super joyful one. It was like a circus opera, so to speak.” She observes placidly that, as her work slips further into the current of mainstream culture, its essence is often lost, and more ominous interpretations proliferate. “When you only view the work over social media, the image becomes very flat. I think there is a vulnerability and a care that you can’t feel unless you experience it personally.”

Indeed, much of Imhof’s work is the result of intimate kinship—her longtime relationship with the multidisciplinary artist and Balenciaga muse Eliza Douglas, the bonds she formed with other artists and performers as a young parent living in artist squats across Germany. Those connections have been essential in pushing the artist beyond the boundaries of a single medium. “I’ve always listened to the people closest to me,” she laughs, “Because I can’t bullshit them.” But as a child growing up in Giessen, a town north of Frankfurt, Imhof dwelt happily in her own universe. “I was an emo kid for sure. There was a quarry with stone walls covered in moss in the woods near my house. It was my favorite place on earth, and I would watch the birds flying up from the trees, imagining the fantasy creatures that would join me.” As she entered her 20s, Imhof cut a more classic emo figure, trading books and quarries “for the basement in the squat I lived in…I was often told I was a Marilyn Manson look-alike,” she recalls with a smile. The mercurial, immersive, fantastical aspects of her practice are born from these years spent interweaving fantasy and reality, a tendency that is undergirded in her work by an urge to investigate the deepest of society’s self-inflicted wounds: climate disaster, nuclear threat, and squalor. “To say, ‘There is no hope, there is no future’—of course I don't want to believe that. But it’s more soothing to me,” she says. “Creating that dystopian feeling is hopeful, because it creates a kind of comfort with that reality. The work is very much a safe place for me.” For Imhof, the goal is not to plunge visitors into her own “apocalyptic” or “nightmarish” vision of the future, as some might suggest, but to hold up a mirror to the world as it already is. “I agree that from another perspective it might be filled with nihilistic thoughts—but for me, those are more honest and more real.”

"EMO" may be Imhof’s first solo presentation in Los Angeles, but it’s unlikely to be her last. “This show is a bit bolder, more immortal. That’s what Los Angeles did to me,” she notes. Reclined on the couch, she considers the next chapter of her career with surprising deliberateness for someone whose art practice seems to be a natural byproduct of her lived experience. “I want to go out of the studios and institutions. I think that’s a good path,” she muses, her voice quiet. “I want to make a performance piece outside here…” she pauses to look at the wooded canyon out her window. “That's what I want to do next.”

in your life?

in your life?