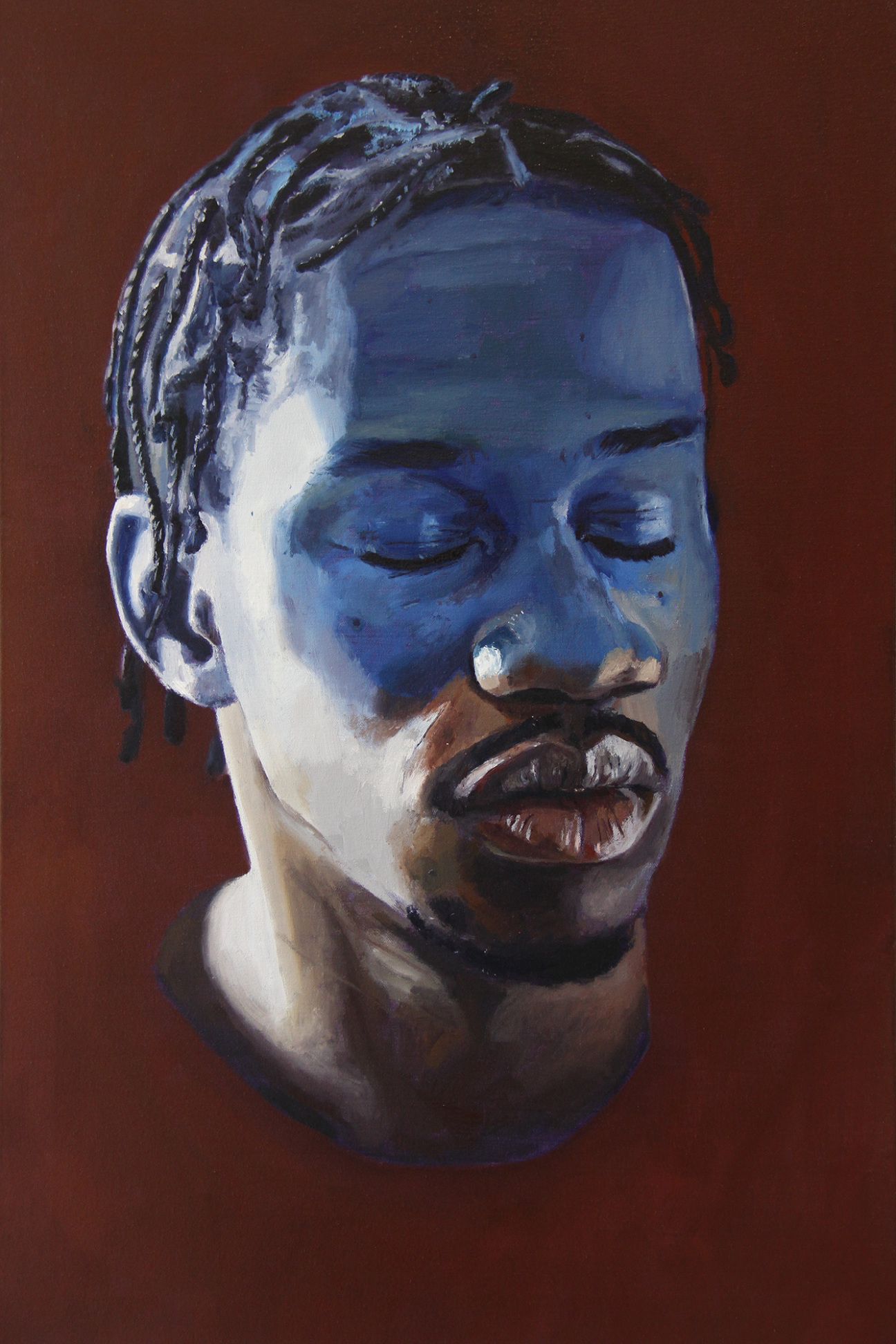

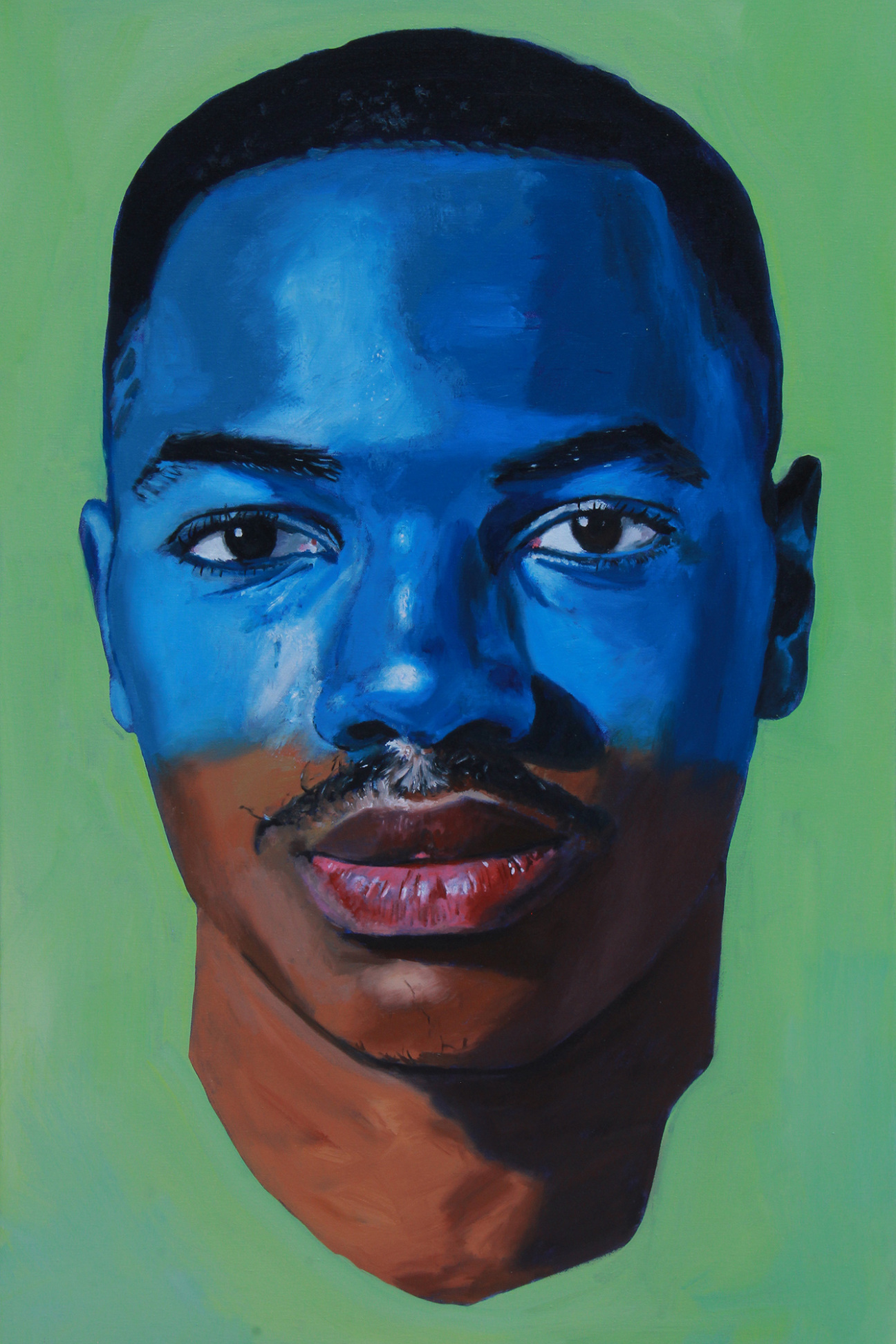

In his 40-painting series “Cyanosis,” William Paul Thomas explores the color theory concept known as "simultaneous contrast" in which the interaction of two colors alters our perception of the image. The collection’s title refers to the medical term for the blueness of skin that results from improperly-oxygenated blood. While the condition generally affects those with paler skin, or with less melanin, the Durham, North Carolina-based artist and educator showcases dozens of Black men and boys experiencing the same phenomenon, though in a more figurative sense.

Thomas’s portraits consist of closely cropped images of the subjects, some with rich blue hues adorning their face, others merely revealing a blue neck or chin in contrast to their warm brown skin tones. The goal of his renderings, Thomas explains, is to underscore the distortion of skin tones while emphasizing each subject’s natural complexion, encouraging the viewer not to consider skin color as happenstance, but as an intentional part of the subject matter. Each subject’s emotional expression, psychology, and individuality are just as important as their skin color.

The idea for the series came to Thomas, 37, during his undergraduate days at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. He was showing his work at the Whitewater Cultural Arts Center, which catered to and displayed the works of predominantly elderly, retired white people, and by reason of his own presence, the artist became acutely aware that his was a different type of work than the local viewers had seen. Years later, while earning his MFA at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Thomas was again one of the few Black students in a mostly white cohort. Having struck up a friendship with fellow Black artist Antoine Williams, he decided to paint works that would spark conversation in spaces where the artist and his subjects were underrepresented.

The subjects featured in “Cyanosis” are all known by Thomas in some capacity, from his brother and his nephew to friends old and new (including acquaintances he only met a day or so before). The artist points out that each subject is a person he wanted to acknowledge, and whose individuality and skin tone he sought to capture. The blue was a way of asking the viewer why these men’s faces were changing color, suggesting that something was amiss. The result is a metaphor—an exaggeration, if you will—modified by each viewer’s predisposition. It also carries the irony that, while Black men and boys feel free to be themselves with family and friends, this is far too often upended when they fall victim to stereotypes. “Their individuality gets pushed aside just because they’re Black,” Thomas explains.

And so begins the symbolic nature of color in the series, an exercise in overcoming biases. When Thomas uses color as a painter, he tries to think about the hue’s aesthetic power and capacity to influence or enhance a picture, while considering the various connotations of a color. Blue, for instance, is reminiscent of the sky or water for some, of deprivation for others, and even of royalty—of triumph or coolness—for more. The possibilities are vast, and the artist enjoys the discourse of learning about all the ways that blue might arise in his works.

In 2021, three paintings from the “Cyanosis” series were featured in “The Visual Vanguard” art exhibit at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, a group exhibition showing the works of Black artists in the South. Artist Stephen Hayes Jr. helped Thomas narrow the selection down to three portraits, one depicting a graduate school peer, Michael Bramwell; another of a student he met at Duke University, Kalif Jeremiah; and yet another student with whom he crossed paths at Barton College, John-Christian Newkirk. Such a grouping of works is meaningful to the artist, for when placed together the subjects might be looking in the same direction—eyes closed in some cases and open in others—allowing the viewers to take in similarity or variety as they examine men of different ages, with different hairstyles and varying expressions and life experiences.

Even the names of the works are nuanced; each title refers to a woman attached to the subjects. Titled Nelly Mae’s Son, the first painting is followed by The Son of Agatha Jeremiah, and then Yvonne’s Baby Boy. Interestingly, while some of his other works are named after the subjects’s sisters or daughters or friends, all three works featured in “The Visual Vanguard” were named after the subjects’s mothers—pointing the viewer to the women who love these men in order to reinforce their value in the world. So while to a stranger the works may initially seem to showcase anonymous Black men, the titles prove that these are real people cherished by others. “The names were chosen in conversation and collaboration with the subjects,” Thomas explains. “And those three individuals all happened to choose their mothers.”

Outside of the the white cube, Thomas hosted a a TED Talk based on “Cyanosis” entitled “The Invisible Notoriety of Strangers,” in which he broke down the meaning of the series, the color theory aspects of his paintings, and his personal connection to the project. While highlighting some of the subjects in the series, the artist also discussed his evolution from yearning for fame to appreciating the anonymity of living in the world as an ordinary person. The talk underscored the impact of deliberately choosing to paint people who are unknown to most viewers—as opposed to painting people who are well known. This, for Thomas, is a crucial point. He clarifies that while society tends to memorialize famous people, only rarely does the mass media shed light on the anonymous Black men who have not been victims of violence, and who are simply going about their daily lives. The artist stands firm in his belief that this invisible notoriety, if you will, is a “worthwhile and necessary creative venture.” And by painting portraits of his friends, family, and those he simply meets in passing, Thomas encourages the public to celebrate everyday people in their immediate surroundings—even strangers.

in your life?

in your life?