Mario Moore wants to keep things interesting. The artist, 35, who lives and works in Detroit Michigan, finds unique ways to stay intrigued in the studio. His personal process starts with an idea to showcase his subjects, a blend of contemporary and historical figures in Detroit, after which he begins considering the material. To bridge the gap between past and present, he keeps history top-of-mind—exploring naturalism and realism through his oils, and creating captivating scenes that are accessible to even those viewers who know nothing about history or art. What are we going through now? Moore posits before starting a new painting.

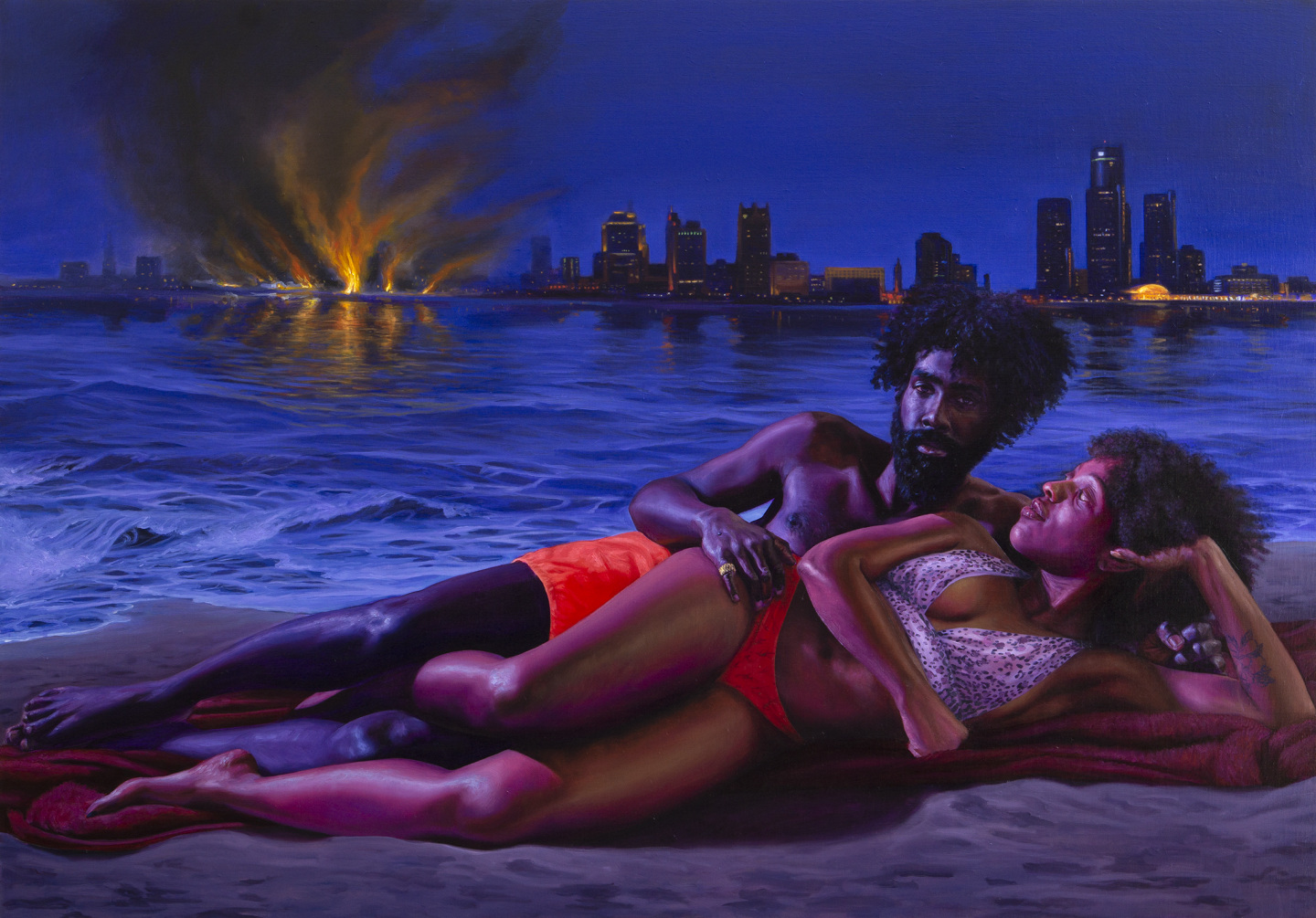

The artist received his BFA in Illustration from Detroit’s College for Creative Studies and an MFA in Painting from the Yale School of Art, and he continues to gather information autodidactically. He spends a great deal of time in bookstores, having recently read A Fluid Frontier, a work detailing the founding of African-Canadian settlements in the Detroit River region in the early 19th century. The book had a deep influence on Moore’s current exhibition “Midnight and Canaan: Detroit” at David Klein Gallery, which explores the history of Black people in Detroit: their contribution to the city, their agency, and their efforts in helping their peers move from the South into Michigan and then on to Canada.

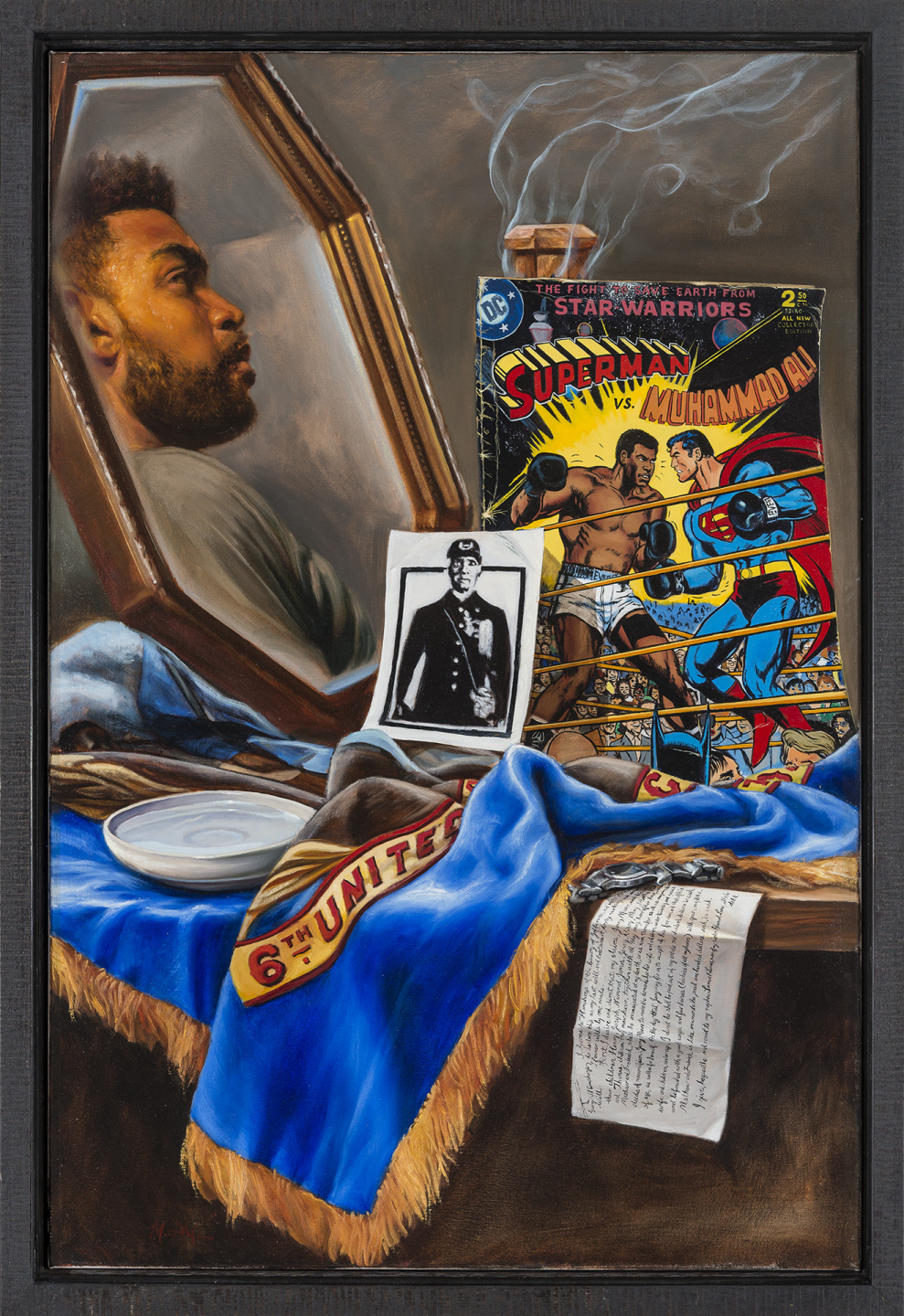

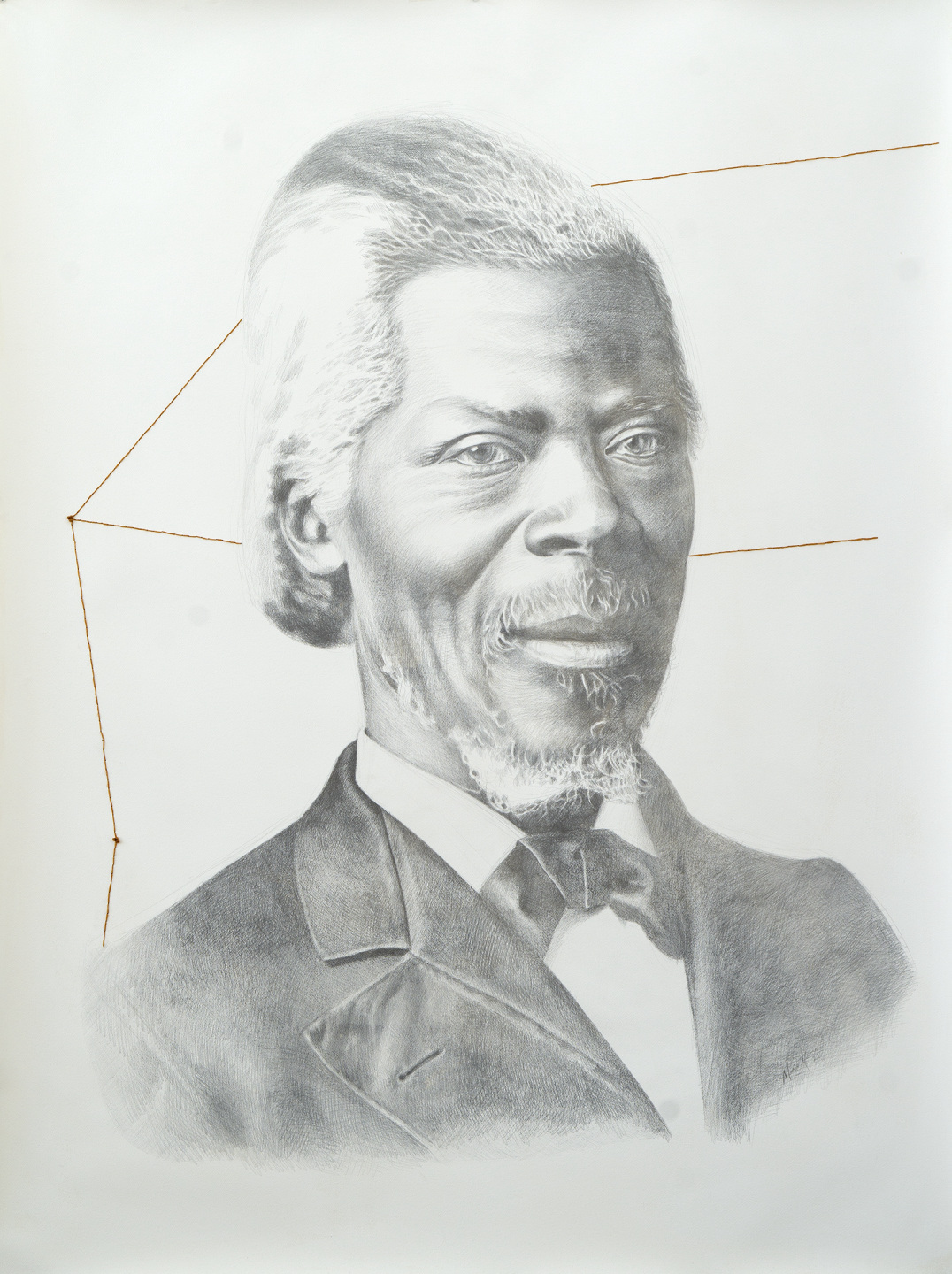

Rooted in historical elements, Moore’s paintings introduce multidimensional subjects, creating scenes that capture the verve of Detroit in a powerful blend of the soulful and the commonplace. Of note in Moore’s work is the notion of overcoming limitations. When the artist learned that one of his ancestors—a great-uncle going back several generations—was enslaved as a child and later fought in the Civil War, he sought to explore the meaning of being a Black man fighting for a country that didn’t want him in uniform. Comparing this to contemporary associations between Black men and weapons—and to January 6, an event in which mostly white men fought exclusively for their own rights, in large part at the expense of the rights of others—Moore leverages his voice to create meaningful conversations.

Charles Moore: Give me a brief background of yourself and how you got into art.

Mario Moore: I grew up in Detroit, mainly around the Detroit Institute of Arts and the College for Creative Studies. My mother was an artist, so she was a big inspiration for me. Growing up around her friends got me thinking about the idea of being an artist. One of her main friends, Richard Lewis, became a mentor of mine, teaching me to paint oils. I took it from there as a young adult, just creating and making every day, and then going on to grad school. From there, after graduating from Yale, it was really spending time in the trenches in Brooklyn and in New York, figuring out what my voice is and what it would mean for me as a professional to be an artist. A lot of those things I took from my elders and the people around me, including the Detroit art community. That's really what's guided me in my studio and in my practice—this idea of making, with endless activity being an important part of that.

CM: I think there's something that is very interesting in the finding of an artistic voice. How do you define yours personally?

MM: Often when I'm at talks or with people I get asked the same question, “How did you find your voice?” I think it's something that just happens. This is not to mean that you're not working towards it, not busy in the studio every day—that type of thing. What I mean is, if you're doing what you're supposed to be doing—if you're making the work, if you're in the studio, if you're learning about art history, if you're doing all of those things—your voice will eventually come through. A lot of young artists are trying to force their way into identifying what that thing is for them now instead of just letting it evolve naturally.

CM: What excites you about your work?

MM: My sensibility and subject matter always have to do with history. I'm always trying to bridge the gap between the past and the present. I'm always interested in making my work appear as democratic as possible, meaning that people from all walks of life, no matter who they are, can relate to my work. Oftentimes, that puts me in the lane of dealing with naturalism or realism, something that's approachable for people that know nothing about history or art. That's really where I find myself the most enthusiastic, the most excited, the most challenged about what I make.

CM: You talk about this exploration in art history, and a lot of your work is rooted in general and African American history. What are you reading to inform you on these matters?

MM: Oh, man, all kinds of stuff. The most recent was a book titled A Fluid Frontier. I just find my way into bookstores and, when I can, libraries. Growing up with my dad, we used to watch all historical movies; such stories are exciting to me and ignite my practice to explore their deeper meaning. A lot of it is just looking at where we are today as a society compared with the past. Sometimes, in the midst of all this research, I’ll find an issue that was happening 200 years ago that we’re still dealing with. So, I ask myself how I can depict that within the work.

CM: Could you give one example of an interesting discovery and how you implemented it in a composition?

MM: I discovered I had a great uncle that fought in the Civil War after being a slave in his youth, and was then freed. That really got me diving into the cause of the civil war. What did it mean to be a Black man putting on this uniform for a nation that really didn't want him to represent them? And how does that pull into the contemporary movement of Black men and weapons? This got me thinking about what happened during January 6. There were a lot of men—white men—standing there with weapons. With how the media portrayed those men, I wonder would it have been the same if it were Black men standing in the capital with weapons? I think the outcome would have been dramatically different. These connections and contributions of Black people to the country, oftentimes unless it’s music or sports, it doesn't really get recognized on that same level.

CM: Right. Tell me about your most recent show at David Klein Gallery, “Midnight and Canaan.” How did it come about and why is that show important to you?

MM: It is really the first show that I've done a solo exhibition about the history of Black people in Detroit and their contribution. Of course, I'm not a historian; I'm an artist. But I love history, and there are some teachable moments I want to articulate—though I'm not trying to teach you anything. I want you to have an open mind to explore what's within the work. The show really is about Black agency and how Black people were helping other Black people flee from the South into Detroit and through to Canada. It was really a porous border, and in the 19th century people were really fluid, not confined by national boundaries. Then again, documentaries dealing with slavery and abolitionism mainly center on the East Coast, while Detroit has the stamp of the Great Migration or Motown or cars. I was excited to learn about the Black community that existed before all of that. What did that community look like? How do I as an artist represent them and how does that affect the city now?

CM: I noticed that a lot of the paintings give the sense of being surrounded by water. In what way is that significant?

MM: It’s highly significant. I wanted you to feel as you walk around the gallery that you're embraced by natural water. Of course, Detroit is beside the biggest body of natural water in the world. Consider what that means, not just as a natural barrier or a border, but as something that allows you to transfer energy or get across to this place called freedom. That really steamrolled the Underground Railroad movement and started to change laws for Black people that were fleeing into Canada. Finding this pivotal moment led to figuring out what this means, what it stands for and how we consider it today.

CM: I'm looking at one work in particular, Tiff Like Granite, What Up Doe. Now I know “What up doe?” is a very specific regional language to Detroit. Could you talk about the jargon used, and how you challenged yourself technically on that painting?

MM: It's funny, you can go anywhere in America, and if you say “What up doe?” They say, “Oh, you must be from Detroit.” That’s the way that we control language or contribute to language. I’m not just talking about Detroit, but Black people in general. My friend, the incredible sculptor and jeweler, Tiff Massey really epitomizes that Detroit sensibility. I wanted to portray contemporary figures like her with that kindred spirit and soul of Detroit. Notice how she's standing in the painting: it's almost like she's unmovable. I want you to feel that kind of presence in her stance, in the figure. And again, she's surrounded by water, but just on a technical or aesthetic plane, she's almost silhouetted by the light that's behind her. As you mentioned, I like to approach a painting with a challenge, meaning I like to keep things intriguing. I asked myself whether I could paint a figure in a way that you see them back lit, but still see their features. That became like the language of the painting. And really that was Tiff.

CM: Speaking of technique and materials, you have this fearless exploration of materials that people dismiss as being dated. Talk about the diversity in your usage of materials and why you feel it's important to be fearless—if you agree with that term.

MM: Whenever I'm thinking of making a work, I always begin with the idea. I call myself a painter, but I like to think of myself as an artist. For me, the question is how do I get across this idea? Whatever material is right for that thing, that's what I'm going to move towards. For example, in this recent show, there are large silver point drawings. I had no idea what the silver point was. I knew I liked them when I would go into the Renaissance galleries and museums and see a [Leonardo] DaVinci, and they would be these really small, beautiful, soft drawings.

When I discovered that the material was literally creating a mark with a piece of silver, I found that incredible. This prompted me to see the possibilities of material that artists had moved away from since the invention of graphite. Think of another artist, Chuck Close, and how he also used old materials in unique ways, like papier-mâché prints. Now what serious artist is working with papier-mâché, I ask you? That set me off making these huge silver point drawings. At the museum, the silver point drawings are really small because the material is so delicate—almost like drawing with a pen. Now when you make that mark, that's it—you can’t undo it. All the same, I decided I was going to scale this up and make these huge silver point drawings. This contributes to their added value.

CM: Fearless is the word. You have to be fearless to work with that material.

MM: Oh, you have to be. You have to go at it. It's unforgiving, very unforgiving.

CM: What type of legacy do you want to leave as an artist? Have you determined that yet?

MM: Not yet. I like to think about a lot of older artists that are still at it. I'll give you one example of an abstract artist here in Detroit—Allie McGhee, an incredible artist; he's got to be 85. He's still exploring, still learning. I can't even visualize what it means to have a legacy because I'm still at it, and I'm going to be still at it ‘til forever. I'm consistently and constantly exploring in the studio, and I don't get stuck in a particular place. Making the same thing repeatedly is so boring. I can appreciate it when artists do want to leave their mark, but that’s not for me right now. I would just feel dead inside. I don’t ever want to hear the comment, “Please yo, hey man, I just saw the last three shows. And it was the same thing.”

"Mario Moore: Midnight and Canaan" is on view until November 5th, 2022 at David Klein Gallery, Detroit.

in your life?

in your life?