In 1975, Ming Smith very nearly turned down the Museum of Modern Art. The Ohio-raised artist and recent Howard University graduate had been living in New York City for only two years, modeling for beauty advertising to pay the bills. When she dropped off her photography portfolio for review, a receptionist assumed she was a messenger, but when she returned to pick it up she was ushered immediately into the curators’ offices. John Szarkowski, the museum’s director of photography who spent his tenure there elevating photography to an art form and making the careers of such figures as Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander, wasn’t in, but as curator Susan Kismaric explained, the museum was keenly interested in acquiring some of Smith’s works. A price was named; Smith, who was used to putting her modeling earnings toward darkroom supplies, was taken aback. “That wouldn’t even pay for my expenses!” she recently told me of the figure. It is incredible now to think of any young artist telling MoMA no thanks, but Smith, whose extraordinary and humanist depictions, especially of African American people are experiencing a quiet but welcome resurgence of attention, certainly did. Kismaric urged her to reconsider. Think about it over the weekend, she said.

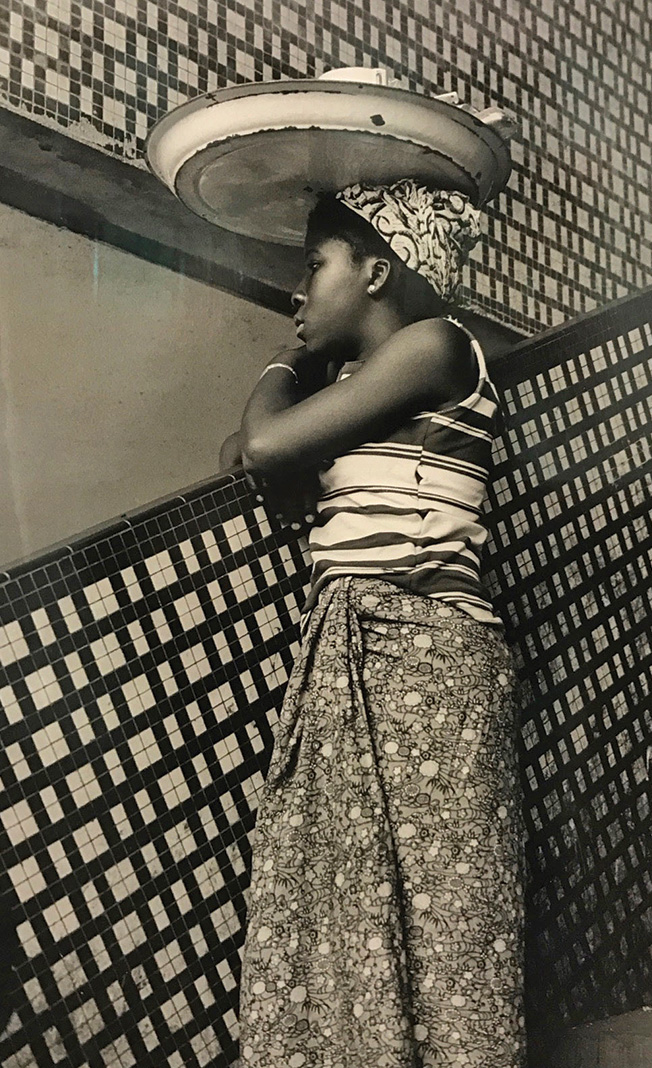

Smith did reconsider, and that year became the first African American female photographer to have prints acquired by the museum’s permanent collection. Today MoMA owns seven of her black-and-white works, including clear-eyed, graceful documentary photographs of mothers and children in Harlem. Also within the museum’s holdings are flashes of the hand-colored and dreamlike multiple-exposure prints and electrifying blur Gordon Parks referred to when he wrote of her pictures years later in an essay for her 1991 monograph “A Ming Breakfast: Grits and Scrambled Moments”: “Wondrous stuff crops up in her imagery, stuffing itself into her sight.”

“I always believed my work was bigger than me,” Smith tells me. “And the MoMA was a milestone. But then for 40 years there was nothing, no shows, no artist talks.” When she says this, she’s exaggerating, though not by much. The current revival of interest in her photographs was largely helped along by MoMA’s “Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography,” a 2010 exhibition which recontextualized Smith’s work alongside that of fellow experimenters in the form, including Diane Arbus, an influence, and her friend Lisette Model. Writing in the New York Times of a solo show that same year at June Kelly Gallery, Holland Cotter praised Smith’s “heartfelt and gorgeous” pictures: “It’s hard to think of another photographer who could set a misty head shot of the writer James Baldwin in a bank of dark clouds over the Harlem skyline and get away with it.” Last year, Steven Kasher Gallery hosted the first major retrospective of Smith’s work; and after the 2017 Brooklyn Museum exhibition “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85,” “I had women telling me they cried when they saw my pictures,” Smith says. This fall, as the Tate Modern-curated exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” lands at the Brooklyn Museum, her pictures again gain a prominent place, perhaps pointing curators to bodies of work still largely unseen.

We are sitting in Smith’s apartment, with its twin views: a window onto central Harlem where she now lives, and the living room, filled with evidence of the last 40 years, piles of large framed prints, and massive, taped-up ones. The floors are heaped with more prints, framed and unframed, and boxes of slides. Smith, a striking beauty in her 60s, darts around the room barefoot among them, with dancer-like elegance. Visible here are years spent in music and traveling the world, as during her marriage to jazz saxophonist David Murray (whose portrait is among the MoMA holdings), as well as distinct and deeply affecting bodies of work, including an early 1990s series made in Pittsburgh, where she photographed people and places of the Hill District where playwright August Wilson set his Pulitzer Prize-winning dramas. Her musician son Mingus, whom she had with Murray, sits at a small desk nearby, poring through his mother’s digital archives.

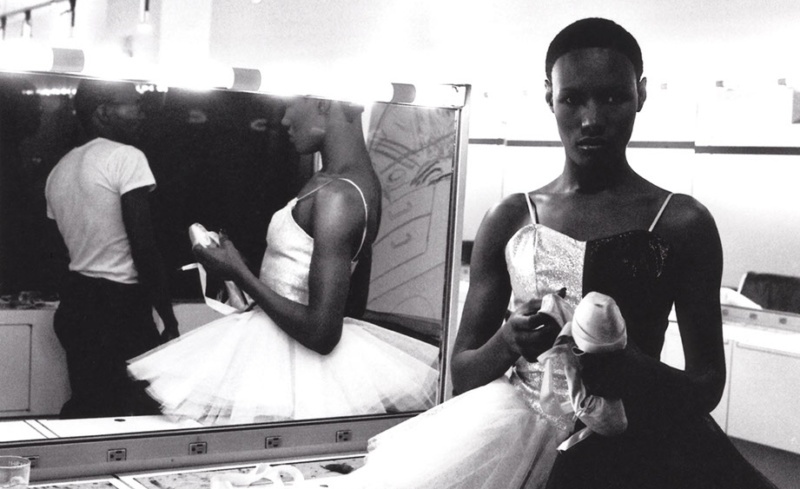

The presence of the “wondrous stuff” Parks wrote of is palpable in this room—the record of an artistic and adventurous sensibility that casts uncommon light on artists and ordinary persons alike. The glitter and sequined cape of Sun Ra in Smith’s deservedly famous portrait of the avant-jazz musician unfurls winglike over his shoulder, seeming to shed layers of stars in his wake, a cosmic path. Face up on another stack of prints is a portrait of Grace Jones, head ecstatically thrown back, in a wash of glitter that Smith enhanced with daubs of pink paint. Jones, who was starting out as a model at the same time as Smith was a friend; “she called me and told me to come out to Studio 54 and take that one,” Smith says. “I knew her before she was ‘Grace Jones.’ But then again, she already was. Grace was always so free.”

Smith frequently refers to the most spectral moments in her work as “gifts,” and light as “spiritual.” Not religious, she clarifies—she means the way Rembrandt uses light or the way Brassaï does. Sometimes the spirit manifests in multiple exposures that create beautifully surprising connections; sometimes it’s simply the arresting, ghostlike blur in her portraits that suggests not just an instant, but a trail left behind. Smith’s affection for her subjects is as evident in her portrait of Alvin Ailey as it is of mourners watching the great choreographer’s funeral procession.

In 2001, after a dozen years living in Los Angeles, Smith returned to New York, the city that made her a photographer. She recalls those early days, living in Greenwich Village, heading out on modeling go-sees and eating at cheap diners near Washington Square Park, where she sometimes ran into Lisette Model and her husband eating dinner too. Model’s fearless street photographs were an early influence; she was also a friend. “I would ask her questions about love!” Smith says.

Just prior to her first acquisition by MoMA, Smith was invited by Lou Draper to join the African American photography collective Kamoinge, whose members included Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks. She recalls meetings at Draper’s studio around 18th and Fifth “where all the photographers had studios then—Avedon, James Moore, Arthur Elgort,” Smith says. “Lou Draper was a great, generous teacher. You felt safe with him.” In her first forays into the darkroom, Smith had forgotten to buy a lens holder and Draper improvised one for her. “So that’s where that started,” Smith says of the handmade borders that still frame many of her prints with an imprecise, elegiac quality.

One of the core Kamoinge principles was the importance of Black photographers portraying Black people, which Smith seized with a surrealistic approach. When she photographed her writer and artist heroes James Baldwin, Romare Bearden and James Van Der Zee, she says, “I needed to present them as they appeared to me: larger than life.” The day of my studio visit happens also to be Baldwin’s birthday, what would have been his 94th. Smith met him not in Harlem, the neighborhood of his birth and formative years, but France, where he spent most of the rest of his life. “I met him at a jazz festival there in the late 1970s,” she says, “but here is where I really feel him. I wanted to show his presence in Black life in Harlem. I wanted to give you something else there, his spirit.” It was a humid day in Harlem, and as I bid Smith and Mingus goodbye and walked out in the streets, violet-gray clouds grew and filled overhead, sending down a fine drizzle of rain and calling out the umbrella sellers who always seem to appear out of nowhere on 125th Street. Looking up at the sky, it was impossible not to think of Baldwin looming there. Smith, of course, had put the picture in my head.