It’s a Monday, and Alicia Keys-Dean sounds awfully serene for someone who’s just gotten off a cross-country flight. The owner of the impossibly silky, dynamic voice that the world first heard cascading up and down multiple octaves 17 years ago in “Fallin’” is unmistakable even in casual conversation. There’s a familiar warmth in her tone, especially when addressing her husband, Kasseem Dean, aka Swizz Beatz. “Want to take this one first, my love?” she says, in moments that make it feel like we’re all sitting in the same room, instead of on opposite coasts.

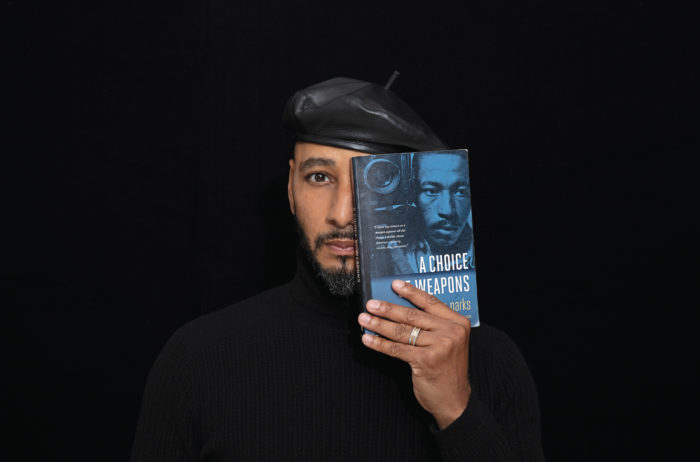

When they began to envision their photo shoot—“It’s our first cover shoot together!” Dean reminds his wife—they looked for inspiration to the work of Gordon Parks, the pioneering photographer, filmmaker, musician and activist. For the past six or seven years, the couple has been friends and co-chairs of the Gordon Parks Foundation.

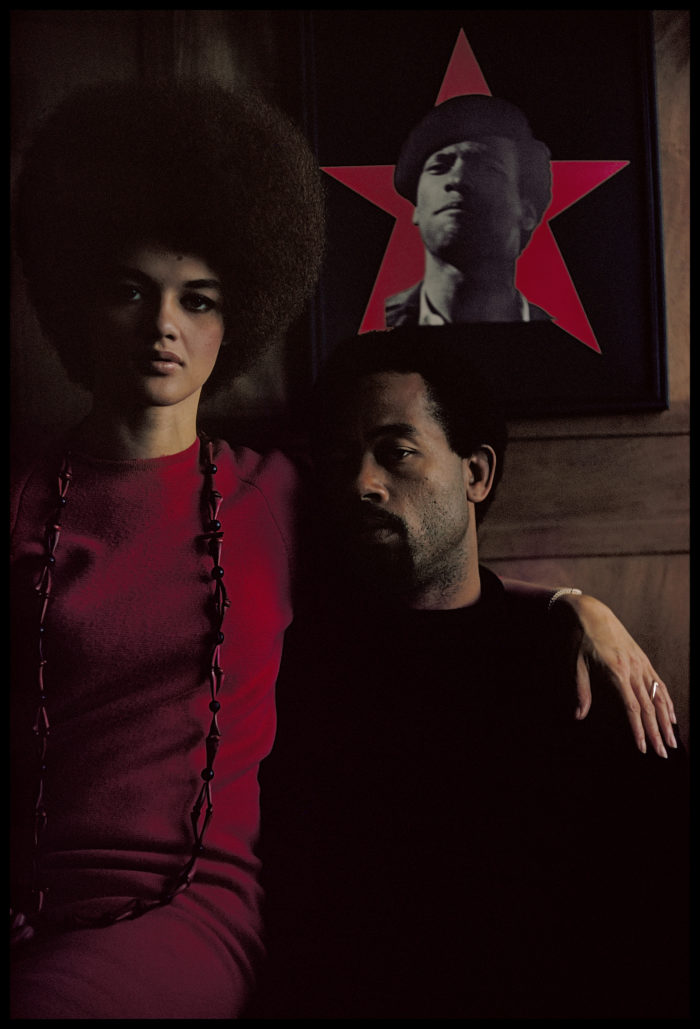

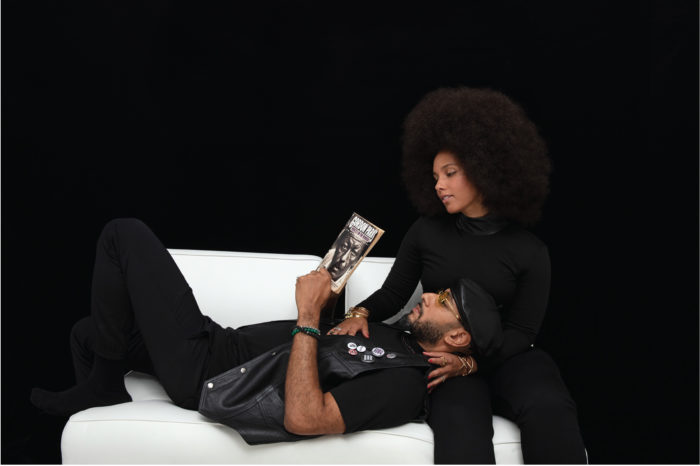

“We were looking at Gordon’s pictures, and Swizz said, I feel like this is the one,” Keys recalls. They had landed on Parks’s portrait of Kathleen Cleaver and her former husband, the late Eldridge Cleaver, made in 1970 when both were leaders in the Black Panther Party. In the photograph, Kathleen, now a law professor and also a friend of the foundation, wears her hair in a beautiful afro; both exhibit the elegance and strength that the Deans embody.

The Deans seem to have become experts in maintaining intimacy and mutual respect. “We’ve been married seven years and we don’t fight, we don’t raise our voices,” Dean says. “It’s all about communication.” A day earlier they celebrated Mother’s Day with their blended family, but today it’s back to business: Keys has just landed in Los Angeles to wrap her last season on The Voice; and in New York, Dean narrates his workday in the low, steady calm that’s propelled him through two decades producing and recording some of the greatest hits in hip-hop and R&B and rock’n’roll (20 years ago he had one of his first major hits producing DMX’s “Ruff Ryders Anthem”). “I get up, vibe with the kids before they go to school,” he says. “Then it’s a few hours of meetings, have lunch around four, and then I’m in the studio, like, all night.” He estimates his next album is “90 percent done, so that’s where my head is.”

It’s been a year of shared accolades and major ventures. During Grammy week he and Keys took home the Recording Academy’s Producers & Engineers Wing 2018 Honors, recognizing their collective strides in the industry—the couple has multiple Grammy awards between them. This year's award mightaswellhavehad“powercouple” written all over it. “Where I’m weak, she’s strong—and vice versa,” Dean says. “We always talk about how we don’t own each other. She owns herself, I own myself, but we come together and have this amazing family. We established that early, both coming out of long relationships. We knew what had worked in our past relationships and what hadn’t. We came to the table a little knowledgeable for this round.”

Keys concurs. “It’s a bit of a challenge sometimes to figure out how to be patient enough to listen and not be so quick to shut down or get defensive, but to pay attention.” That kind of empathy and awareness translated into their shoot with legendary documentary, fashion and fine art photographer Jamel Shabazz. “I mean, I’m like a Panther fanatic,” says Keys. “This was made when Eldridge was exiled in Algeria. It’s very powerful when you think about that time and where we are in the world now, politically, culturally. To recreate it with Jamel felt so genuine. It represents everything about the spirit of Gordon Parks.” Shabazz cites Parks as one of the major reasons he first picked up a camera. For four decades he has photographed what he calls a “vision diary” of African American life on the streets and subways of New York City. Shabazz was among the honorees at the foundation’s annual gala in May, where the announcement of the Dean acquisition—now the largest private holdings of Parks’s images—was also made. The works, which span Parks’s diverse and prolific career are now a part of The Dean Collection, the couple’s philanthropic organization and family collection of international contemporary art.

“Hank Willis Thomas is provoking my mind the way I want it to be provoked right now. Like, what does it mean in this particular culture to be a mom to sons of young black men? What do I think about it, what do I want to do about it?” —Alicia Keys“They made extremely thoughtful choices,” says Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., the foundation’s executive director. “Really, it’s a comprehensive overview of Parks’s work—his iconic civil rights pictures, his early fashion work, portraits of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, as well as important, lesser known photographs.” Next spring, in partnership with the foundation, the Dean Collection’s Parks archive will have its premiere exhibition at the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at Harvard University. After that, says Kunhardt, Jr., “Swizz and Alicia have a lot of ideas about where to bring this work, and plans for ways to keep it active and visible and give it the kind of educational programming it deserves.” As Dean puts it, “People need to see this type of greatness to inspire themselves.” For two artists with such divergent careers that they have to pointedly schedule each other in, art has been a mainstay. Early in their relationship, Keys chose the Guggenheim as the location for a surprise party she threw for Dean—“something I knew he would love but also that he would not expect.” “You know, we have known each other since we were like 16,” says Keys, of their early meeting through mutual friends in the music industry. “Back then I would never have imagined he was this avid art lover, but he has been that way for so long.” She grew up in Hell’s Kitchen attending the Professional Performing Arts School, and admiring her mother’s reproductions of Gustav Klimt paintings (“the tenderness of the embraces, and those golds and fiery reds”). Dean, raised in the Bronx among family who started Ruff Ryders Entertainment, was working overtime to prove himself to his uncles and aunt as a producer.

When he started racking up studio hits, Dean began to collect instinctively, notably amassing an impressive collection of Basquiats. His very first art purchase, though, was an Ansel Adams photograph. He bought his first home when he was around 18 and he wanted to fill the walls. “I grew up around graffiti and I’m a huge fan of graffiti art, but I looked to photography, to this very different landscape,” he says. “It took me to this world that nobody had ever put in front of me. It’s crazy, now that I’m saying it. This is the first time it’s ever made sense to me.”

The Dean Collection continues to collect artists from diverse backgrounds but its strongest interest is artists of color, globally—recent acquisitions include Nina Chanel Abney, Dr. Esther Mahlangu, Sanlé Sory, Omar Victor Diop. “The collection started not just because we’re art lovers, but also because there’s not enough people of color collecting artists of color,” Dean says. “We don’t own enough of our culture. So we want to lead the pack in owning our own culture and owning our own narrative instead of waiting for someone who’s not part of the culture to tell our story for us.”

With notable exceptions like the Parks acquisition, the collection now focuses almost entirely on living artists. “We want our kids to get to know all these artists who are going to be in the history books,” says Dean. “Our son vibing with Kehinde Wiley, that’s priceless.”

“It’s a beautiful dance,” says Keys. “I’ll hear Swizz on the phone to one of our artist friends at 3 a.m. and it sounds deep from where I sit. He really cares about having longtime relationships that are genuine and stimulating and reciprocal.” Recently, she’s found personal resonance in the work of conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas. “He’s provoking my mind the way I want it to be provoked right now. Like, what does it mean in this particular culture to be a mom to sons of young black men? What do I think about it, what do I want to do about it?”

The Dean Collection’s ongoing evolution includes initiatives aimed at empowering and promoting artists outside its own holdings too. In 2016, Dean launched the No Commission Art Fair, pop-up events held in the Bronx, Art Basel, Shanghai and elsewhere, offering its curated artists the chance to exhibit their work for free, and receive 100 percent of any sales. This spring the collection announced the TDC20 St(art)up, which will award 20 $5,000 grants worldwide for proposals and business plans for independent art shows. “We want to help teach sustainability,” Dean says.

“Like, how do you set up something yourself so that you don’t have to try to figure out how to get in a system that you don’t like, and that doesn’t include you?”

Recently the collection made what Dean calls a “major purchase” of the photographs of Deana Lawson, a recipient of the 2018 Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship. “The thing with photography—whether it’s Gordon, whether it’s Deana, whether it’s Sanlé—you can’t escape the truth in those moments,” he says. Almost in unison we both mention Zadie Smith’s recent New Yorker essay on Lawson, in which she wrote: “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling. But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

“Her work shows you a Black love story,” Dean says. “And my thing is: How do you define that? We want to say this is Black love, or that is Black love, but the truth is, love is love.”

Earlier, he’d told me, “Alicia and I really believe that photography is the future,” and now, as he begins to speak passionately about Lawson’s work, I see what he meant. Dean is especially attuned to the domestic scenes Lawson meticulously recreates, the greater honesty that her fictions reveal, the way her interior worlds cause us to reexamine our interior selves. “When I look at Deana’s photos, I know people whose places look just like that now,” he says. “I know a brother whose house looks like that, I know a sister whose house looks like that, and most of us want to run away from that reality. Deana’s photos are not letting you run away and that’s very important in the culture. We got to come home and look at ourselves in the mirror.”

He pauses briefly—the producer’s natural understanding of when to insert a beat, to make the music that follows hit just right. “As we know, most of what people are seeing on social media is not the truth,” Dean says. “What you’re seeing in Jamel Shabazz is the truth. What you’re seeing in Gordon Parks is the truth. What you’re seeing in Deana Lawson is the truth. That’s why their work is so spectacular to us. It embraces the truth. It embraces the roots. And there’s beauty in that.”