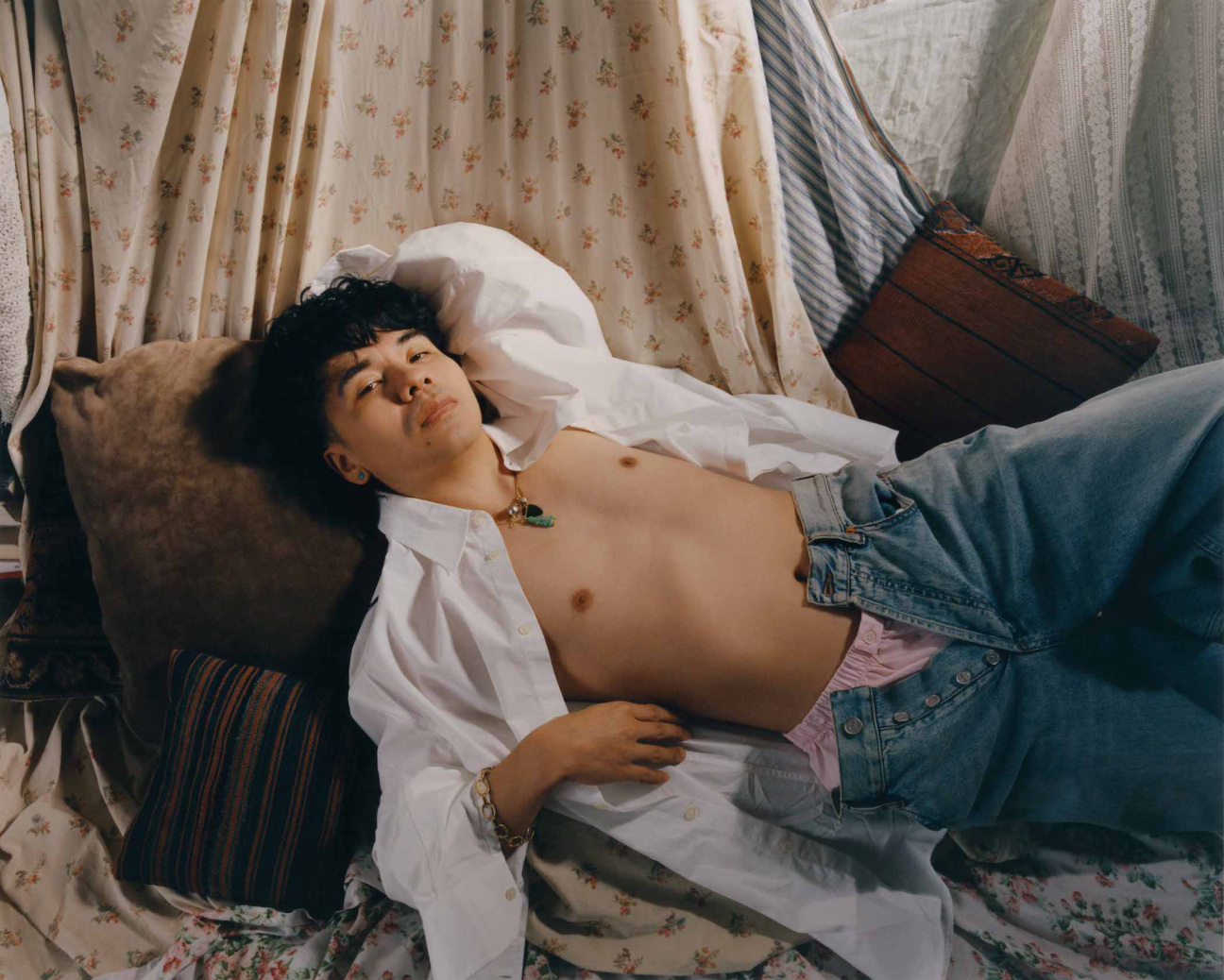

Not enough people talk about how irreverent Ocean Vuong is—how he once wrote a poem containing a measurement of his longest pubic hair, or that he smirks and laughs a lot more than most portraits have yet captured. Take, for example, a line from a recent poem: “I bet you never guessed / that my ass was once a small-town / wonder.” Yet the image commonly put forward of the celebrated writer is something of a brooding, burdened monk.

“Every time I do a profile it’s like—I do a photo shoot for five hours, and we’re laughing and having a great time,” explains Vuong, who lives in New York and Northampton, Massachusetts, over a rainy-day coffee in SoHo. “Then the photos come out, and here’s this sad, serious, totally self-loathing poet.” Where is the portrait that conveys how silly and gleeful he is, Vuong asks. Joking about a manic moment in his creative process, he exclaims, “No one has ever done this before! I will put a rim job at the center of a novel!”

But lately, Vuong has been exploring forms beyond books. “I like to learn more than I like to write. I don’t want to loiter in ignorance,” he muses, turning on a dime from self-parody to sincerity. By now, many know the 35-year-old’s remarkable origin story—his mother Rose’s separation from her family when Saigon fell in 1975, her immigration to the United States with Ocean in tow when he was just 2, and his precocious and meteoric rise in the literary world with poetry she couldn’t read.

Following his acclaimed poetry debut came the 2019 novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, a bildungsroman echoing his own life, written as a letter to the protagonist’s mother. It was published just months after Rose was diagnosed with breast cancer, and just one season before she died of it.

Though it’s been nearly five years since she passed, Vuong still speaks of her in the present tense. When I pointed this out, he smiled faintly, like he was remembering a little secret about time. Vietnamese doesn’t exactly have a past tense for verbs, he tells me, just a modifier at the end of the sentence that tilts the past back over it. “I live near Emily Dickinson,” he adds, as if she might pop over with a batch of gingerbread cookies at any moment. “Literally in my head right now I’m thinking, She’s across the river. That’s where she lives.”

What is perhaps most particular about Vuong, however, is not the dramatic circumstances he was born into, but the unbridled joy and persistent humor he displays both in person and on the page. When a group of Australian teenagers sent him a nonslaught of pained DMs after an excerpt of his novel was featured in their English final, Vuong posted the exchange online: “BRO FFFSSS FAM we gonna fail … wat was it bout,” one young Aussie complained. “Bro. Godspeed, bro,” Vuong replied. Even the title of his 2022 poetry collection, Time Is a Mother, can be interpreted both philosophically—how time gives birth to us, continually—or as an incomplete sentence: Time is a motherfucker, a weighty yet wry statement about grief.

During the early days of the pandemic, Vuong adapted his first novel into a screenplay, a project with A24 that’s moving ahead after a year in Hollywood-strike purgatory. “With a screenplay, you have to write poorly but usefully,” he says of the challenge. However, as a creative writing professor at New York University, he still encourages his students to “write a novel that only the novel can do,” rather than books that try to beckon a film deal from the page—the sort of thing he once heard a Hollywood guy describe as “user-friendly IP.”

At the invitation of his friend Peter Do, creative director at Helmut Lang, Vuong wrote a poem for the brand’s 2024 Spring/Summer collection. It was printed on the floor of the presentation venue, and on shirts the models wore on the runway. Like the sartorial crossovers of Jenny Holzer and Robert Mapplethorpe before him, Vuong’s was more performance than commerce; the shirts were not for sale.

A self-portrait he took during a 2008 road trip was also used in taxi-topping advertisements for the collection, part of a journey into photography that he began after realizing that his writing would always be unintelligible to his mother. Those first photos, captured with a borrowed camera, were of “suburban ruins, post-industrial Hartford, sunsets, whatever.” His mom’s reaction to them was, “Buồn quá,” a common but difficult-to-translate phrase that means, “Oh, so sad,” implying that “there’s a kind of beauty to loss,” he recalls. “She informed me that that was what I was capturing.”

Though those first photographs were a vehicle for communing with his family, a conversation with the legendary Nan Goldin in 2022 hastened his return to the practice. As Goldin was taking his photo for a magazine feature, Vuong confessed he’d been shooting more lately, but felt vulnerable about it. “There’s nothing creepier than showing the world exactly where you stood and what you saw … Even in my more autobiographical writing, it’s all smoke and mirrors,” he says.

Vuong remembers Goldin suggesting, “If you’re doing it for this long and you don’t share it, you start to betray yourself,” adding that, “It’s the error in the camera where all the poetry is.” It was a revelation to realize that what he wanted to do with photography was the same as what he wanted to do with writing. The weight of the realization was so powerful that he had to step away from the shoot for a moment to gather himself.

Photographs document how an artist intersects with a moment in time, an evergreen challenge of presence and attention, though the role of photography has transformed since Goldin first came of age. While photojournalism, in part, hastened the end of the Vietnam War, we now live with a deluge of images from Gaza with no end in sight, a paradoxically distant yet present horror Vuong and I can’t help but discuss. “Maybe it was a bit naive, but I never thought that cycle would happen again in real time,” he says. “But the present is the most myopic place … We think we have access to the archive, but it’s a false sense of omniscience.”

It feels very 2024 for a conversation about a newish photography practice to melt into a little plea for photography to somehow solve everything, to move us away from a present marked by genocidal wars. How very Ocean to situate us in the arc of history before returning to the moment, reminding me that “the only access we have to the present is through this room.”

For all his exploration of new forms, fans of Vuong’s prose will be glad to know his second novel, aptly titled The Emperor of Gladness, is due out next year. Here’s hoping it makes clear to his readers that he’s far from the brooding poet of photo shoots, and that the central force in his life is joy, in all its visceral, messy glory.

All clothing and accessories by Valentino.

Grooming by Eloise Cheung

Set Design by Daniel Horowitz

Styling Assistance by Trevor McMullan and Gabby Weis

Photography Assistance by Sam Dole and Miller Lyle

Set Assistance by Nick Kozmin and Bethany Wong

in your life?

in your life?