The entrances to both venues of the 60th Venice Biennale’s International Art Exhibition show the same artwork: a suite of neons by Palermo-based artist duo Claire Fontaine reading Stranieri Ovunque, or Foreigners Everywhere, in over 20 languages. This piece, part of a series begun in 2004, gave the Biennale its title. To encounter a sign with those words in an exhibition may be unsettling—it can sound aggressive, perhaps intolerable in an era where xenophobia is dominant—but not here. For a show about the foreign, its curator, Adriano Pedrosa, has focused mainly on sameness.

Throughout the Arsenale and the international pavilion at the Giardini, abstract paintings sit next to abstract paintings, landscapes are shown alongside other landscapes, textiles hang by more textiles. Arab modernist Aref El Rayess’s wonderful depictions of deserts and cityscapes from the 1980s lead to Aycoobo’s Amazonian landscapes painted in the 2020s, then to his father Abel Rodríguez’s botanical drawings of trees and forest animals, which are also from the past decade but reference 19th-century scientific taxonomical drawings.

Mahmoud Saïd’s 1923 portrait of an Egyptian woman, Haguer, is shown below Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s 1930 portrait of an Indigenous woman, Mancacoyota. These works share subjects, or are contemporaneous, but convey radically different ideas and societies, which are not spelled out in the display. In lieu of juxtaposing political positions or sensibilities, creating a system of meaning that enhances the works’ contextual charge, Pedrosa has opted for flat visual links.

Curating, simplified to its barest bones, is an act of pairing. But is it meaningful to see an Angolan artist and a Saudi-Palestinian artist use a similar methodology to discuss distinct political concerns? In Kiluanji Kia Henda’s 2015 The Geometric Ballad of Fear, photos of homes are prismed through the metal bars in intricate shapes found in buildings across Luanda. Those actual railings are then used to assemble a large sculpture, A Espiral do Medo, 2022.

Just behind it hang silk fabrics by Dana Awartani in Come, Let me Heal Your Wounds. Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones, 2024, where every piece of silk is a requiem for a historic site in the Arab world destroyed by war. Awartani’s installation is tragically designed to accommodate new examples, and the Biennale’s version includes testimonies to places destroyed in Gaza in the past months. Henda and Awartani both make abstractions of built environments in order to create a haunting image of reality, only from disparate contexts and discussing different issues.

The austere brick building of the Arsenale, Venice’s former shipyard and armory, provides a dramatic background for Antonio Jose Guzman & Iva Jankovic’s large-scale installation Orbital Mechanics, from the series “Electric Dub Station,” 2024, in which massive indigo textiles hanging from the ceiling create an acoustic environment for music; shown next to Claudia Alarcón’s similarly expansive textile abstractions, it creates a nice tension—rare in this Biennale—and exemplifies that materiality does not spell out a single way of working. But a more generous display allows viewers to focus, as is the case with the room dedicated to Isaac Chong Wai’s videos Falling Reversely, 2021–24, showing a group of dancers whose movements emulate falling, then trying to reestablish balance.

Before the Biennale opened, when the list of over 300 participants was released, many initial reactions focused on it being the first in recent times to spotlight more dead artists than contemporary ones. The focus on art history is intentional: Pedrosa argues that 20th-century artists from Latin America, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia are still not well known internationally, their inclusion in the Biennale a form of payment for a historical debt.

But seeing their works alongside others that closely resemble them (and that echo Western art, such as in Chilean painter Camilo Mori’s beautiful portrait of his artist wife holding a book on a train, La viajera, 1928, which explicitly mirrors the style of Cézanne) makes this idea of global modernism feel far from remarkable. Most historical works are hung salon-style, in multiple rows, giving a distinct impression that it was the gesture of including these works—rather than actually showing them—that matters more.

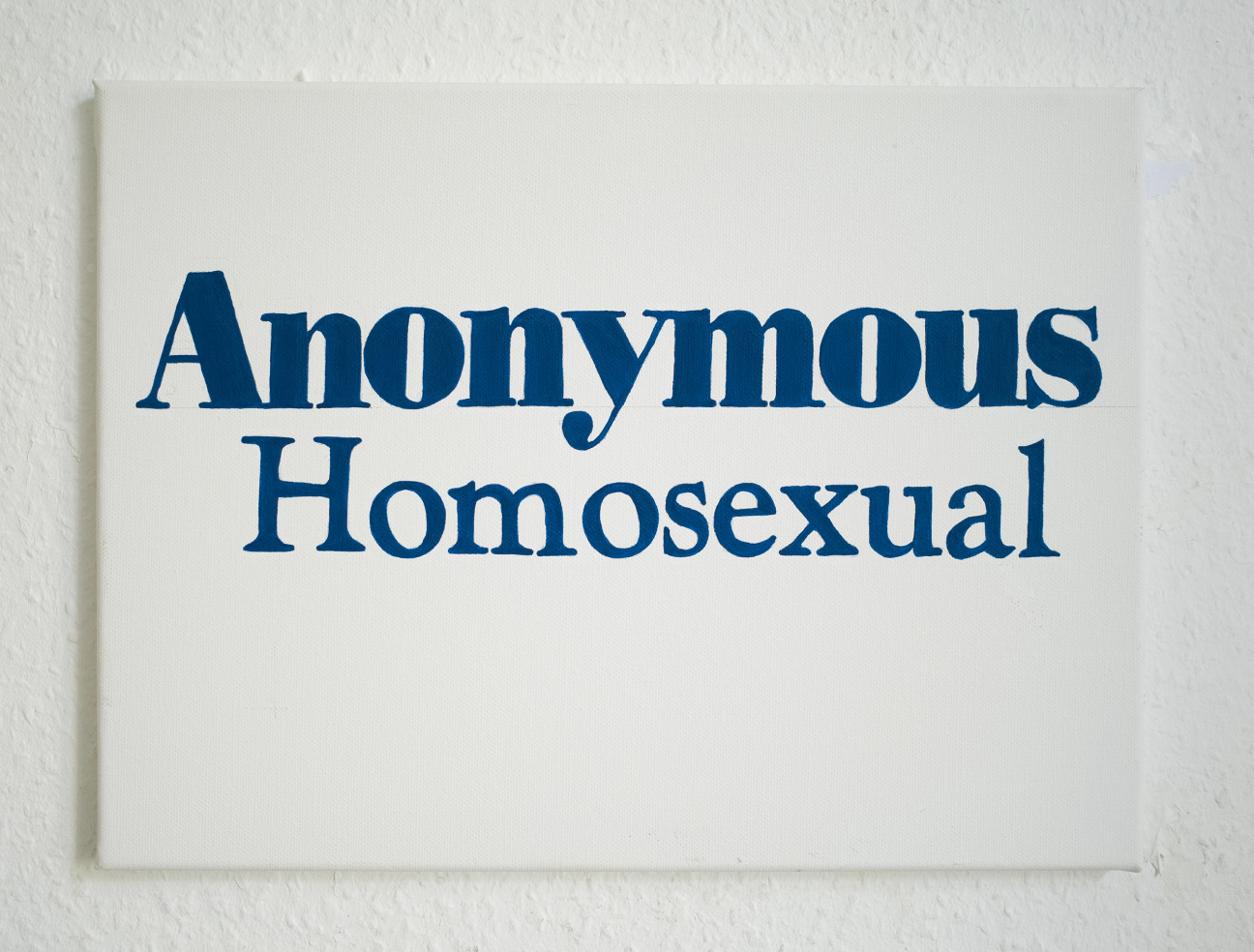

Pedrosa is Brazilian, the first Latin American curator of the Biennale, and also its first openly queer curator. In interviews, he has acknowledged that his curatorial decisions are related to his personal stakes, namely the inclusion of many Indigenous artists, and work that addresses queerness directly, from Dean Sameshima’s canvases that read “ANONYMOUS HOMOSEXUAL” and “ANONYMOUS FAGGOT” to Sabelo Mlangeni’s striking photography of LGBTQI+ people in Lagos and Johannesburg. Who we are affects how we approach art, how we make it, see it, talk about it, curate it. It matters.

In a show that signals discovery, supposedly uncovering works that have thus far been ignored, it’s the particular—the felt minutiae of a person’s lived experience—that feels most potent. Charmaine Poh’s video What’s softest in the world rushes and runs over what’s hardest in the world, 2024, includes slow shots of a home and children playing, against which several same-sex couples talk about their experiences of parenting.

Two women in Singapore describe the difficulty and pain of how only one of them is recognized as the mother of their child. The work is intimate, warm, empathetic, and specific. Stripping away the layer, or label, of foreignness, and reinvesting in people’s realities creates an image of a world composed of individuals, not international platitudes.

in your life?

in your life?