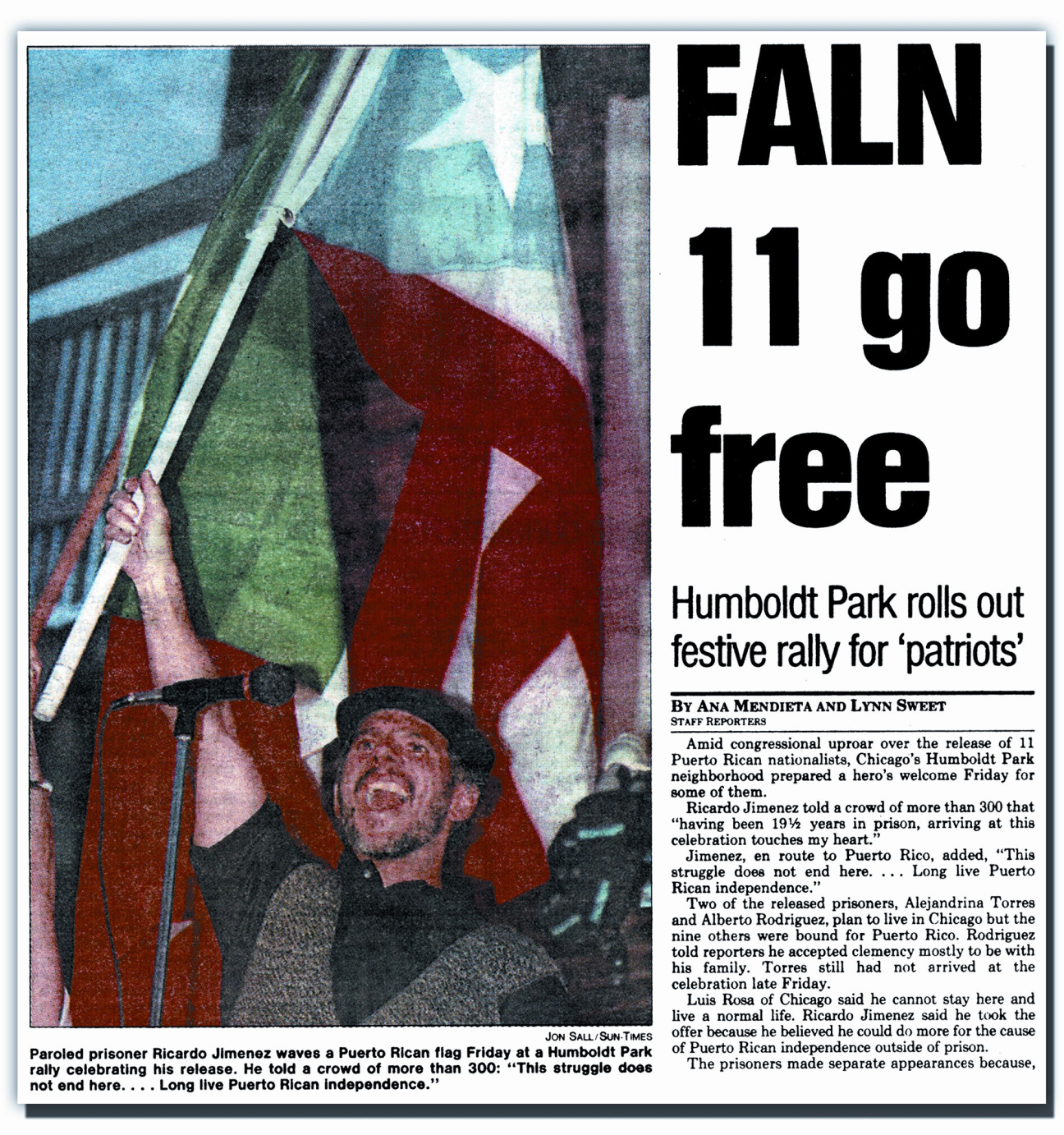

Standing in front of his portrait, former political prisoner Ricardo Jiménez was moved to tears at the opening of the Museum of Contemporary Art’s “entre horizontes” exhibition. There he was, waving the Puerto Rican flag as he and 11 other prisoners were released from prison in 1999, having been granted clemency by then President Clinton for involvement with the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN). A quarter of a century after the President’s attempt to bolster relations with the island nation, Puerto Rico remains the legal property of the United States.

“There's always this misinformation around the status issue, saying Puerto Rico is a part of the United States. It's not—it's a possession,” says exhibition curator Carla Acevedo-Yates, who was born in San Juan. “I use that language, and it's facts, not opinions.” “Entre horizontes: Art and Activism Between Chicago and Puerto Rico” is exacting with the words it uses, all presented first in Spanish, not English, on its wall plaques. The artwork on display is interspersed with artifacts brought forward by members of Chicago’s sizable Puerto Rican community, eager to see their history immortalized in an institutional context.

There are portraits of long-passed family members, photography of how neighborhoods used to look prior to gentrification, and contemporary pieces that serve as evidence of how the community’s en-masse mid-century immigration laid the groundwork for a thriving artistic network. Locals helped Acevedo-Yates and her team edit texts and searched their homes for archival documents and photographs that would provide further information. The result is a referendum on the place of Puerto Ricans in one of the country’s most segregated cities.

“We don't shy away from the difficult conversations,” explains Acevedo-Yates. “The role of the museum is to be a space to have those difficult social and political conversations.” Here, the curator offers an inside look at putting together a visionary exhibition.

CULTURED: How was it working on something that I imagine hits close to home, being from Puerto Rico?

Carla Acevedo-Yates: I feel really proud of this exhibition, and it is definitely a historic exhibition because I don't think there's been a show that has approached these histories in this way in Chicago, especially at an institution like the MCA. I moved to Chicago in 2019, and I had friends that had come to Chicago to do their masters in fine arts. Artists, if they want to pursue these degrees, they have to move either to the States or elsewhere. Usually they go to New York and Chicago. I also knew that Chicago had a sizable Puerto Rican community that was very activist, more so than New York. It was these two different horizon lines … the artistic and the social justice component.

When I was speaking with artists, they were always telling me how Chicago is a city by the lake; there's this very important relationship to water. For me, being Puerto Rican, and for Caribbean people, there's something about the lake—it's so immense that you don't see the other side. I came up with this title that was very poetic, that serves as a metaphor of thinking about what it is to live and work between two horizons, between two cultures, between two languages.

When I started doing research with my team, there was this really interesting history of how Puerto Ricans were brought to Chicago to work. It was called the Chicago Experiment, and it was part of a modernization project. Men were brought to work in foundries and in the steel mills, and women were brought in as domestic workers. That was in the '40s … and when they came, they faced a lot of hardships: housing discrimination, the language issue. Some of them brought their children, and it was difficult for the children to insert themselves within the education system.

The community really organized themselves to create institutions and organizations to fulfill and satisfy their own needs. I thought that was really powerful. I really learned working with José E. López from the Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Jan Susler—the attorney at the People's Law Office who led, alongside the National Boricua Human Rights Network, the case towards the liberation of the political prisoners—that this community is really an intellectual space.

CULTURED: These are obviously expansive political issues that you're covering. Was it difficult to distill that down into one exhibition?

Acevedo-Yates: There's necessarily a selection process within this narrative. It's trying to gather touch points that were important to tell that story within a condensed space. The first one is the historic migration that I was telling you about. I divided it between four different sections within archival tables. The first one is telling that story through materials, and we gather materials from institutions, from newspaper archives like the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune, but also personal archives.

The second part was telling the story of the rebellions in both ‘66 and ‘77. The third one is the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriqueña and the campaign for the release of the political prisoners. So that is a very important touch point within the story. Beatriz Santiago Muñoz's video is kind of the anchor that is bringing together the artistic and the social justice components of the show.

There was no way that the release of the political prisoners [could have] been achieved without this idea of solidarity across different political ideologies … so it was important to express how the concept of solidarity and transcultural solidarity is important for the community to thrive, not only within the Puerto Rican context of bringing different perspectives and different political sectors together to release the prisoners, but also in terms of the Latiné context of having solidarity across different identities of the Latino diaspora community.

This show was built with the community. That's very different from anything I've done and it's very different from what the museum has done previously, in the sense that there was buy-in from community members. They reviewed the material that we presented. They gave us suggestions and edits to the text that we presented. They went through their personal archives, giving us photographs of their families to show. When the community came to the opening, which was a huge party, they really felt that it was their exhibition.

CULTURED: You're talking about the artistic community's role in politics or in raising these issues, and I'm wondering how the MCA navigates that as an institution.

Acevedo-Yates: In the Puerto Rican context, you can't separate art and politics and that's part of the argument of the show. I've always felt a lot of freedom in this institution to think about those hard questions, especially the Puerto Rican question, and its colonial relationship to the United States. I mean, there's no other way to put it, and in the exhibition, it's very much there. In the intro text, it's very clear that Puerto Rico belongs to, but is not a part of, the United States. That is a Supreme Court ruling that is called Casos Insulares.

[The curation] is based on historical arguments and telling the story from a historic perspective. That's helpful because it also has this educational component. At the MCA, I never felt like I couldn't tell these stories in the way that we want to tell them, and I say “we” because I feel like I'm already a part of the Puerto Rican community [in Chicago]. That's the story that we want to tell with all of its complexity.

CULTURED: This exhibition was shown both in English and Spanish as part of the museum’s larger initiative to go bilingual. What has the response been to that decision?

Acevedo-Yates: Since “Forecast Form,” [opened at the MCA in November, 2022] the MCA is a fully bilingual institution—Spanish and English. What I did with this show is a little different because the Spanish comes first. I want to speak directly to those communities, and there's necessarily a hierarchy when there's bilingual material presented. That's just the way things are placed on the wall; if a text is side by side, either the English or the Spanish has to come first from left to right.

The MCA is leading the way on bilingualism nationally for sure, because we now have staff that are dedicated to this and that are thinking very intentionally about a style guide that makes sense for museums. There's a real commitment from the institution, not only to hire people like myself that are building a curatorial program that is a long-term commitment to certain histories from different perspectives, but also through the bilingual initiative [and] not doing the Latino show in Spanish and English and the rest of the shows in English. [All] content is accessible and available to them in their native language.

CULTURED: Is there a particular moment from curating this exhibition—one conversation you had or one thing you learned—that really stands out in your memory is particularly influential?

Acevedo-Yates: I can say a couple. I've received a lot of letters just saying thank you from community members, and I have a little folder where I keep those letters because that's what drives me to keep going and to keep doing this work. The conversation that I had with José E. López during the opening, that was a really special moment because the Puerto Rican community is so supportive of their people. They all showed up—the auditorium was packed.

Another thing that I was very, very touched by was former political prisoners coming to see the show and being moved to tears because their story is at the MCA. There are people who came like, “That's my father in this photograph.” They recognize themselves. I remember that there's a Carlos Flores photograph of Lincoln Park—Lincoln Park was a historic Puerto Rican neighborhood before there was displacement and gentrification—and they're like, “I remember that record store.”

It was really special how it brought so many memories to people and, again, the former political prisoner moved to tears because there's a photograph of him shortly after he was released from prison with a Puerto Rican flag. He came and saw that. That was so special to me and to him, saying, "I can't believe these histories are at the MCA," and people from all walks of life can come and learn about these histories that are largely unknown, even in Chicago. I keep receiving emails, and I don't want it to close.

"Entre horizontes" is on view through May 5, 2024 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

in your life?

in your life?