The first Whitney Biennial was the equivalent of a middle finger to the art establishment. It was 1932, two years after the Whitney Museum’s founding, and the show’s curators broke with tradition by allowing artists to select their own work. Ninety-two years later, it has gone from representing defiant table-rattling to a seal of institutional approval from one of America’s most influential museums.

The Whitney Biennial is one of more than 250 biennials, triennials, and quinquennials that have sprung up around the world in cities ranging from Milan to Montevideo. These sprawling group shows symbolize the globalization of the art world and the belief that culture can spur tourism and economic activity. They also serve as a critical third space, outside the gallery and the museum exhibition, to explore ambitious, challenging art and ideas.

Throughout its history, the Whitney Biennial has been a barometer for what is new and note-worthy in American art. Perhaps that’s why, more than almost any other biennial, it has been the subject of bitter criticism and roiling controversy. American critics, artists, and viewers feel a sense of ownership over it—it’s their story, their cultural history written in real time.

This year’s edition, titled “Even Better Than the Real Thing” and opening March 20, is organized by longtime Whitney curator Chrissie Iles and first-time biennial curator Meg Onli. Iles is the only person to have tackled the show three times (she also organized the 2004 and 2006 editions). Onli most recently served as director of the Underground Museum in Los Angeles. Well before they joined forces to put together the biennial, the duo had begun talking on the phone on Fridays, covering everything from big-picture curatorial philosophy to how best to install new media art.

Together, they built an intergenerational and multi-disciplinary exhibition featuring 69 artists and two collectives. The lineup includes trailblazers like Mary Kelly and Suzanne Jackson as well as up-and-coming and mid-career talents such as Jes Fan, Ligia Lewis, and Ser Serpas. To consider the role of the Whitney Biennial in the broader cultural ecosystem, and to explore what biennials of all kinds have done to and for art, CULTURED assembled a roundtable of experts.

Ben Davis is the national art critic for Artnet News and the author of the 2023 book Art in the After-Culture. He has been reviewing biennials for two decades. Tuan Andrew Nguyen, an artist known for creating transportive, deeply researched video art, has participated in more than 10 biennials, including the Whitney’s, in the past six years alone. They spoke with Iles and Onli in January.

What was your first experience ever visiting a biennial?

Ben Davis: It was 2003, and I was living in Madrid and studying at the European Graduate School. As part of that program, we went to the Venice Biennale. It was the relational aesthetics biennial curated [in part] by Rirkrit Tiravanija. I remember two things: One, there was a heat wave that year and everyone was soaking through their clothes. Two, it was massive—an endless feeling of worlds within worlds. I remember the intellectual excitement of feeling like I didn’t know exactly what I was looking at.

Tuan, you said the first biennial you were aware of was the 1993 Whitney Biennial. That has become known as the “identity politics” biennial, and it is now considered one of the most influential shows of the 20th century.

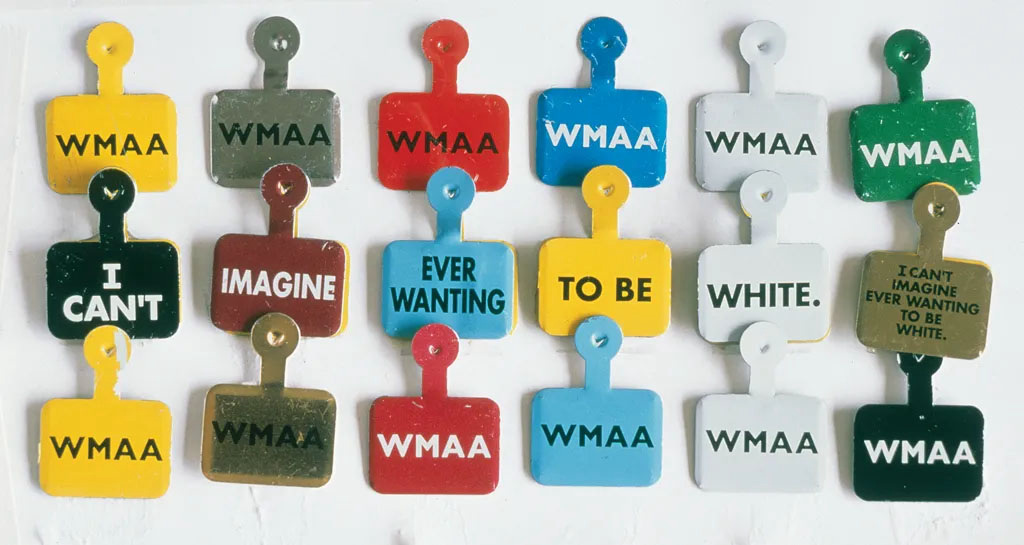

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: I went to the University of California, Irvine. I was pretty determined to double major in biology and art, just so I could expand my application to medical school. One of my art professors was Daniel Joseph Martinez, who created the pins in the biennial that said, “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white.” We were given essays to read about the ’93 Whitney by another professor. It was mind-blowing. It gave me an understanding of the urgency of political art.

Chrissie Iles: My first job was at the Venice Biennale as an assistant in the British Pavilion. So I lived in Venice for four months and started out seeing it from the inside. I also came to New York for the opening of the ’93 Whitney Biennial. It was my second visit to America, and it was transformative in ways I didn’t understand at the time. It was a very specific, critical conversation, and very American.

Meg, this is the first biennial you’ve curated. In preparation, you’ve read every single Whitney Biennial catalog and interviewed many previous curators. What was the best advice you got?

Meg Onli: Thelma Golden, who organized the ’93 biennial, said, “Don’t read the press.” Adrienne Edwards, who did the 2012 biennial, said to think carefully about what Chrissie and I want to say at this exact moment. Henriette Huldisch, who curated 2008, said, “Everyone’s going to hate it, so just enjoy the process.” That really scared me. I describe the Whitney Biennial as curating on a speeding train. There is such a short period of time to make this show, and it has more attention on it than any show I’ve ever worked on.

Davis: It’s interesting that the ’93 biennial is such a touchstone for people, because it was completely panned, yet it’s the one everybody remembers as a landmark. Part of why biennials get such a rough go from critics is because they have come to be defined as not just a show, but a referendum on who is in and who is out—a referendum on the moment. It becomes everybody with an opinion about the moment’s opportunity to air what they really think.

Iles: That is strictly a New York view, since most culture is made in the Global South. So in terms of who’s in and who’s out, I think it’s very interesting to go to the São Paulo Biennial, to Documenta. It’s important to not get sucked into what you’re describing, because who is that conversation for?

Onli: What you’re talking about feels very market-driven. Inevitably, all of us are part of an art market, but it’s not at the forefront of my mind when working on the biennial. We wanted to get away from this discovery model. I was trying to turn away from that impulse of, What’s the new hot thing? Biennials are some of the only places where you can synthesize a group of ideas together fully.

We found artists were returning to ideas of the psyche, psychoanalysis, and the body. At first, we were surprised, but given the past year and a half—in which politics have been limiting people’s bodily autonomy, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the limitations on trans people being able to medically transition—maybe it’s not so surprising. The majority of artists in our show are people of color, and there’s a long history of what it means to be looked at, to be consumed, to be put on display. Chrissie, you said at one point, “What is America but a psychodrama? What is America but a fiction?”

The relationship between biennials and the art market is interesting. Ben, you once looked at all the artists who had participated in biennials over the previous five years and found that there was almost no overlap with the mainstream art market. If you ask people who cover the market what they think of the artists most frequently shown in biennials, they’ll say, “I’ve never heard of them.”

Iles: I don’t agree that there’s a biennial track and an art market track. I think a lot of galleries are extremely knowledgeable about art, including art that’s not for sale. And they often take more risks than museums do.

Onli: If we look back to the ’32 annual, the earliest iteration of the Whitney Biennial, you could just go and buy the work. Until the ’90s, multiple artists would be in back-to-back biennials—and that would show how robust their markets were, how collectible their work was. So there is this longer trajectory. It’s not as if you’re in the biennial and suddenly you are a famous artist. But there are substantial changes—you’re able to get a teaching position. Your prices change.

Nguyen: People have told me that I am not a gallery artist, that I am more of a biennial artist. For a very long time, I didn’t care about the market. It wasn’t until much later in my career that I realized that I depended upon the market to survive. And part of surviving was gaining the proper visibility: getting the art out there at certain biennials to have potential gallerists and collectors see it. That was especially important to me at the beginning of my career because I’m based out of Ho Chi Minh City, not New York, LA, London, or Paris.

Davis: The age of the biennial is also the age of the art fair. They grew in tandem as effects of globalization. I looked at the numbers, and I do feel there is more of a bifurcation over time between the biennial world and the market world. Curators just aren’t including Adrian Ghenie, for example—someone who is minting money and has incredible support from collectors. Do people undervalue these biennials as an alternative channel of symbolic value, cultural value, intellectual value? I feel like people have a split view: Biennials are these jet-setting events and they are exhibitions that hold space for art that isn’t necessarily represented in the big galleries.

Iles: One of the things you’re talking about is the difference between taste and ideas. Those can be very different. But 90 percent of the people who see the biennial are not “the art world.” They are the general public. And in America, where there is very little cultural education in high school, museums are how people learn about culture. Conversations about biennials radically swing from talking about ideas to talking about logistics. So when an artist like Tuan is creating an ambitious film for a biennial, he has to create it and he has to figure out how to finance it. That represents a departure from the job of what we’d call a “market artist.”

Nguyen: There’s a lot of pressure to represent your best work when you’re in a biennial. I work mostly in moving image, so the cost of production is quite high. Many times, I have to raise a significant amount of money to produce the idea that was presented to the curators. And often times I might only have a year, a year and a half if I’m lucky. I feel like 75 percent of the work is finding the funding and then physically getting the work there. Crating and shipping is a different headache.

Onli: There’s more new work than we anticipated in this biennial. Once we told the artists who else was in the show, they often would want to adjust their work because they saw themselves in dialogue with others.

Iles: The thing about artists is, say you choose a piece for the biennial. Then the artist says, “I want to change the color of the carpet, I want to re-edit the film, I want to do this or that.” So although you think you’ve chosen this piece, you’re not just taking something and installing it. You’re working with the artist.

Onli: Our average studio visit was three hours. Our longest was 12. We didn’t want to feel as if we were shopping.

Davis: Did the artist with the 12-hour visit get into the biennial?

Onli: Yes. It’s an incredibly good sign if you want to talk to someone for 12 hours.

Meg, you said you didn’t want to work with any artists in this show with whom you’d worked before. This is also the first time you’ve worked with non-Black artists as a curator. What has the process been like?

Onli: All my shows have been around Blackness, so I’ve never worked with an artist who wasn’t specifically dealing with Black studies and Black cultural production. I have also been very focused on video. When I saw Jordan Carter [a curator at the Dia Art Foundation], he was like, “Oh, it’s going to be the video biennial, right?” I said, “Well, Chrissie and I are really drawn to painting and sculpture right now.”

Okay, there’s still a lot of video. But we wanted to think about what it meant to take you into an environment. We have two lighting designers working with artists on this show. We talk a lot about the choreography that occurs in building any exhibition. How do you draw someone close? How do you move someone back? How do we convince people to look longer than three seconds?

Nguyen: I left art school with this idea that no one’s going to watch video art, especially at a biennial. But most of my videos are longer than 30 minutes, sometimes more than 60 minutes. I’ve taken it upon myself to see if I can captivate audiences. It might be a practice in self-defeat. It takes a lot of space to create these black boxes for projections, and a lot of people don’t even walk through the curtains to watch.

I’ve talked to a lot of curators, and they have the same experience Chrissie mentioned, where the artworks are changing until the moment the biennial opens. So you can’t really anticipate what the work will be—you’re actually curating practices together and putting practices into dialogue. I wonder, are biennials just really about the artist list?

Iles: For me, biennials are about ideas, not the artist list. What does an artist list mean? You see a name, and you think, Oh, I know that work. Well, do you? They might be switching from painting to sculpture, for all you know. Looking at a list beforehand, you can’t anticipate the feeling of all those works being brought together. And afterward, you can’t explain what it felt like when no one had heard of some of the artists on that list. It feels more exploratory, experimental, and radical than it looks in retrospect. In a way, that’s the magic of the biennial.

Social media has defined the narrative emerging from biennials, and Whitney Biennials in particular, in recent years. Tuan, you were in the 2017 biennial, which is best known for the controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, 2016. What was it like to be in a biennial that was part of an Internet firestorm?

Nguyen: I have mixed feelings about it. The conversations and some of the writing that came out of the Dana Schutz situation were worthy of our time and attention. I still haven’t really processed it, to tell you the truth. Part of me just put it to the back of my mind. I did follow the twists and turns from Vietnam. And there were conversations had about other works in the show, they just didn’t take center stage. It seems like biennials have been riddled with controversy of late—and maybe even earlier.

Davis: The Guerrilla Girls were doing agitprop about the Whitney Biennial in the ’80s. But I do think social media has changed everything. The vast majority of people are now experiencing these shows through digital mediation, and the Internet inherently selects for controversy. The truth is, the media is disintegrating at the same time, more and more desperately catering to the present. There’s less time for reflection. It creates the perfect storm where you get the one signifier that defines these events.

I actually thought the last Whitney Biennial was really good, but it had this real feeling of withdrawal. There were vast amounts of time-based work, you really had to sit there, and there was a theme of opacity. I read it as a curatorial reckoning with that reality. The 2017 biennial was also the first one after Trump’s election. I remember the vivid feeling that it had been planned mostly before the election with an expectation of landing in a different environment. People were processing the vulnerability, shock, and urgency of that moment and treating the show as a referendum on that.

Onli: I don’t want to get too into the Dana Schutz painting itself, but I will say that the history of American media has been very comfortable disseminating images of mutilated Black bodies. That’s a fact. And there’s a way in which art media and media in general participated in disseminating those images. That’s not to say that I didn’t think the Dana Schutz painting and having those conversations wasn’t important, but I do want to flag that we are not outside of our own influences. We’re not outside of the media landscape that is America. That image played with something that already circulates in a really complicated way. I can’t say I’m surprised that it ended up having this huge impact.

Davis: I asked people at the end of 2019 to select individual artworks that defined the previous decade. The only one everyone agreed on was Open Casket.

Iles: Which is interesting, because the painting in the same show of Philando Castile by Henry Taylor, who’s a Black artist talking about Black death, didn’t get that recognition. That’s problematic to me.

Davis: Okay, I have a question. At the end of the press preview, when they’re asking me to leave, I’m always like, “I haven’t seen everything. I haven’t seen all the video.” Is your ideal spectator someone who sees it all?

Iles: I don’t think so. Curiosity—actually putting the phone down and being with the work—is much more important than seeing everything. Of course, if you see everything, you’ll understand it better. But we have tried to make a show that doesn’t feel overwhelming or exhausting. It’s really important to make a show that has a haptic quality to it—that makes you want to leave your computer and actually experience these things.

Onli: I am a chronically ill person. I’m not a person who necessarily wants to visit for a really long time and see everything. I might catch a quarter of the show and come back. I might feel like sitting with one video. I want to encourage people to pick their own pace. Ben, I heard you saw all the videos in the last biennial. How many sittings did you do to get that done?

Davis: It was two full days. That was me feeling like other people were going to write reviews without having seen the whole show, and I challenged myself not to do that. But that’s a luxury—a lot of writers are very pressed for time, and they’re going to pick a few things and read a few labels and make some generalizations. I see it as a challenge of the form. You get hit with this barrage of stuff all at once. I imagine as an artist, there must be a little bit of competition, right? With other artists in the show?

Nguyen: That’s a whole other roundtable, Ben.

in your life?

in your life?