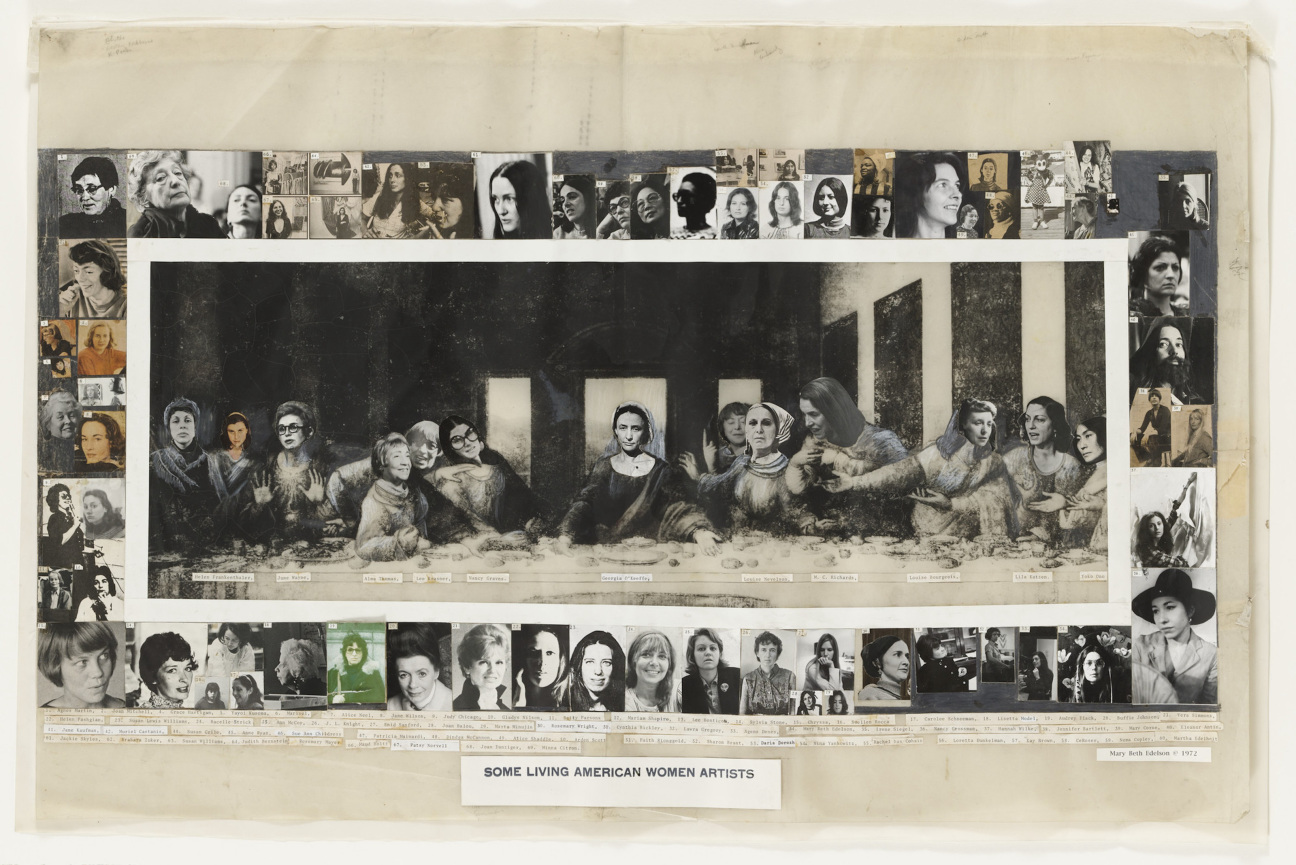

The canon of women artists is one both intentionally and recently built; often overlooked, underestimated, even outright dismissed, women were painted as muses rather than artists for most of Western art history. Although giants like Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Mary Cassatt, and Frida Kahlo made names for themselves during their lifetimes, it wasn’t until the 1960s and ‘70s that the art world began to take note of a wider creative movement—one that saw women addressing patriarchal structures, political upheaval, ecological collapse, and bodily autonomy through an intersectional gaze.

Five decades after this initial boom, the landscape for women in the arts has changed dramatically. According to the 2022 Burns Halperin report, contemporary museums in the U.S. acquire 48.2 percent of work by women on average. Institutional leadership also reflects a gender shift: 20 of the 31 museums in the survey have women as their chief curators and/or deputy directors.

Yet, these sea changes are met with other stagnant metrics, especially under the hammer and at home. A 2022 Forbes article spoke of the “$192 billion gender gap” for work produced by women sold at auction. Symptomatic of a broader environment that treats motherhood as a penalty, artists who bear and raise children have consistently reported a loss or slump in income after childbirth. These two financial consequences barely touch the latent and manifest biases and burdens working female artists are met with—a terrain that is compounded by factors like race, ability, geographical location, and socio-economic background.

The seven exhibitions below, dating from the ‘40s to today, show how creatives and curators alike have taken these circumstances into account to disrupt what we expect from an artist—and art history.

“WACK! Art and Feminist Revolution,” 2007

Location: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Featured Artworks: Martha Rosler, Hot House, or Harem, 1966. Judy Chicago, Orange Atmosphere, 1968.

Why It Changed the Game: Expansive and patchworked, WACK! captured a sense of the 1970s feminist art wave. Featuring over 120 artists—including Judy Chicago, Faith Ringgold, Marina Ambramović, Ulrike Ottinger, Betye Saar, Chantal Akerman, Cindy Sherman, and Joan Semmel—the show brought together the work of women across many mediums and countries to better understand this pivotal post-war moment.

A Few Words: “WACK!” curator—and current MoMA PS1 Director—Connie Butler acknowledged the difficult nature of recreating a sense of widespread feminist action. “My ambition for ‘WACK!’ is to make the case that feminism’s impact on art of the 1970s constitutes the most influential international ‘movement’ of any during the postwar period,” she says in the exhibition catalog, “in spite or perhaps because of the fact that it never cohered, formally or critically, into a movement.”

“Womanhouse,” 1972

Location: California Institute of Art

Featured Artworks: Judy Chicago, Cock and Cunt Play, 1972. Kathy Huberland, Bridal Staircase, 1972. Judy Chicago, Menstruation Bathroom, 1972.

Why It Changed the Game: Quite literally born out of a need for space, artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro created the Feminist Art Program—the first of its kind in the U.S.—at CalArts after Fresno State College did not provide them with proper studio access. Along with their students, they took over an abandoned Victorian house in Hollywood, which they completely renovated before staging their explicitly feminist exhibition three months later.

A Few Words: Only open to female visitors on its first day, “Womanhouse” attracted thousands of visitors over its month-long run and even gained national attention, including a writeup in Time. As Chicago noted in the exhibition manual, the portrayal of a certain sect of women’s lives struck a chord. “The age-old female activity of homemaking was taken to fantasy proportions. ‘Womanhouse’ became the repository of the daydreams women have as they wash, bake, cook, sew, clean and iron their lives away."

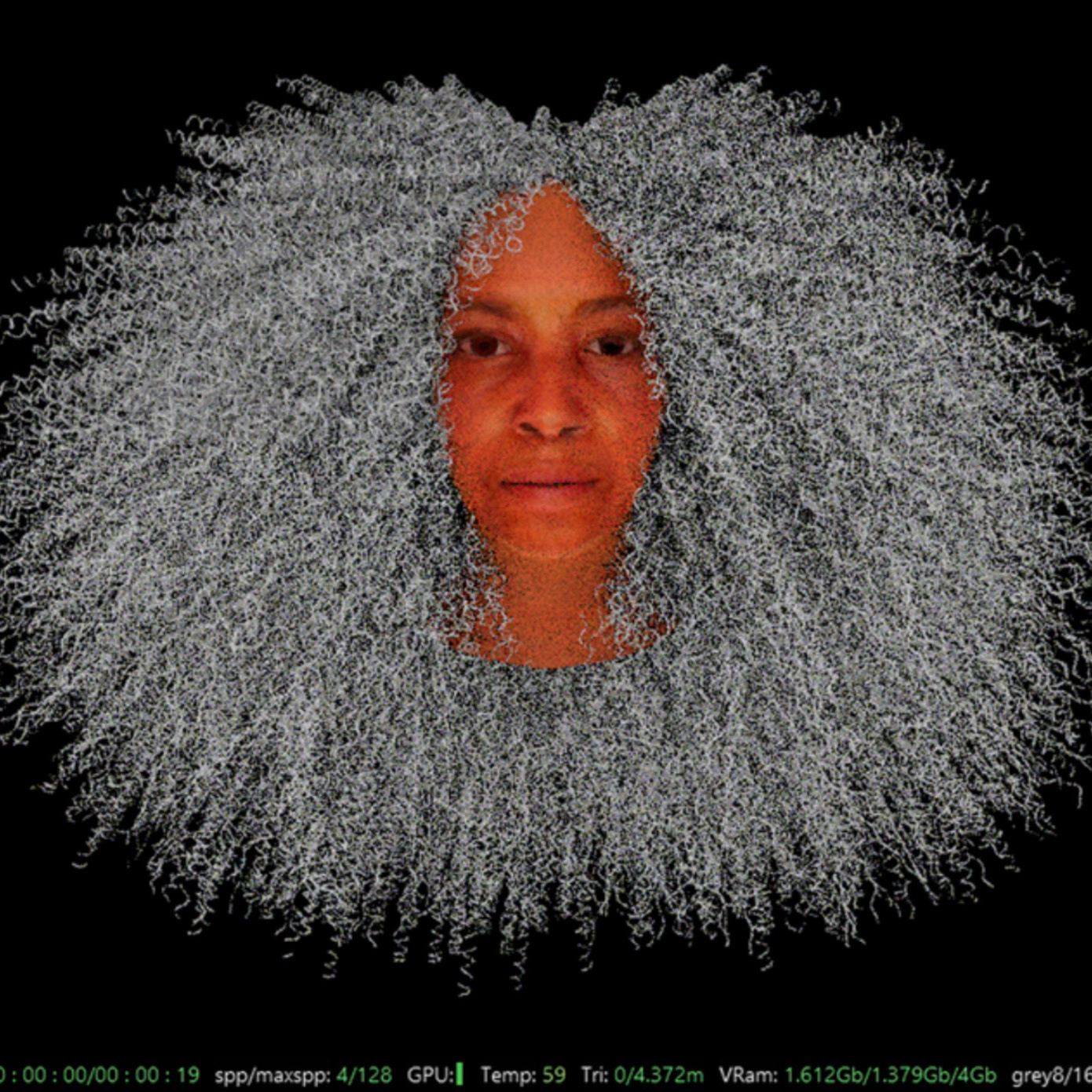

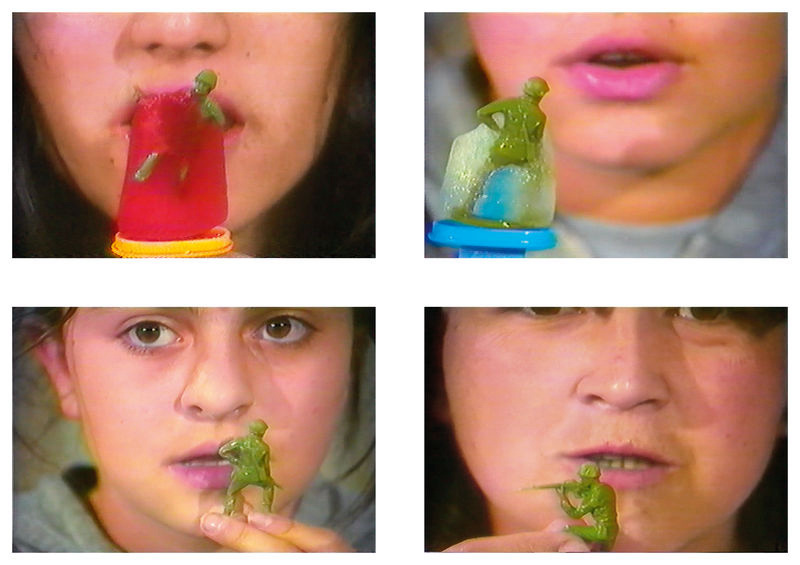

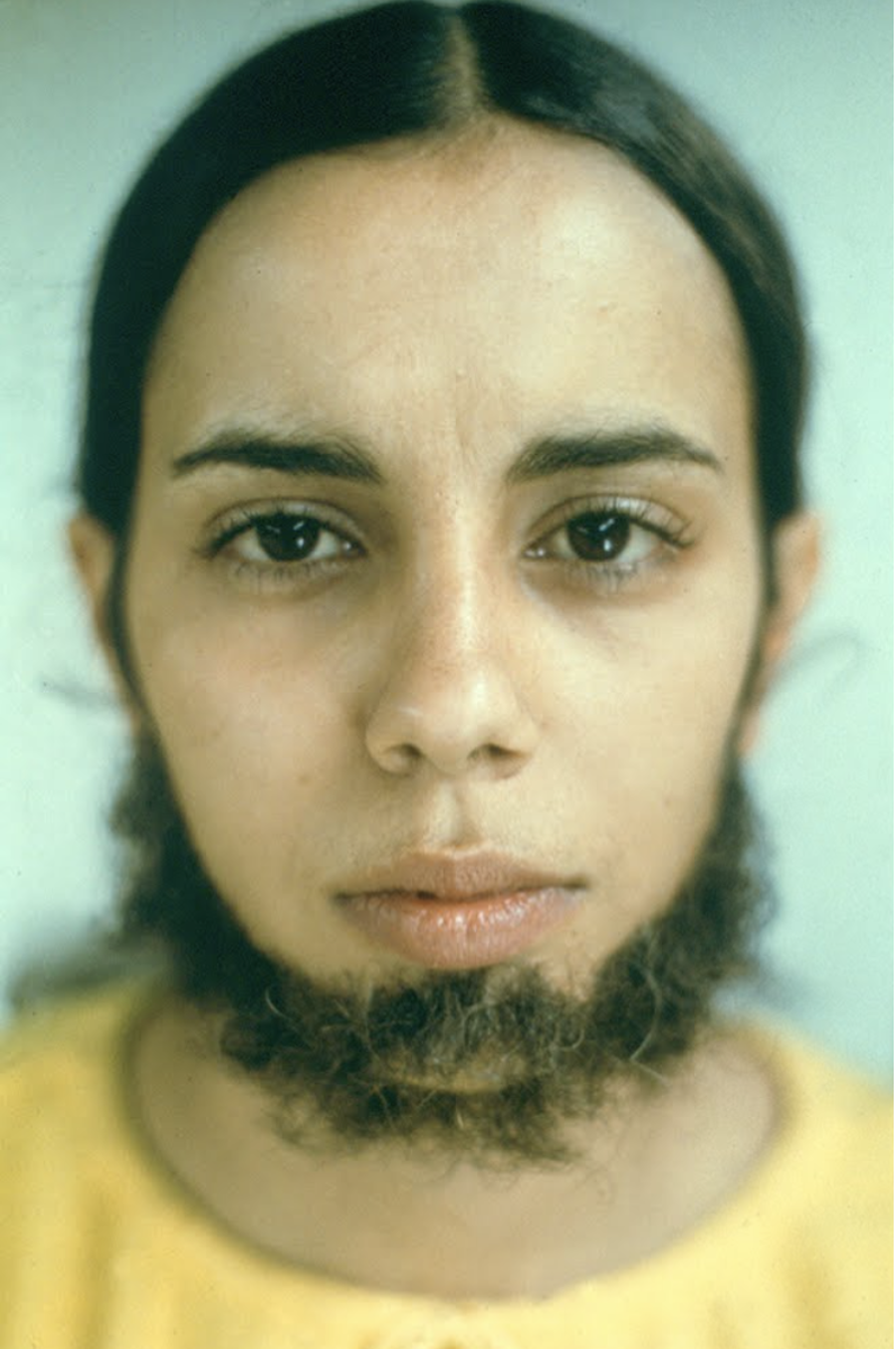

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” 2017

Location: Hammer Museum

Featured Artworks: Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants), 1972. Teresinha Soares, Caixa de fazer amor (Lovemaking Box), 1967. Gloria Camiruaga, Popsicles, 1982–84.

Why It Changed the Game: Presenting artworks from over 120 Latin American and Latina artists—many of whom were mostly unknown to a U.S. audience—“Radical Women” captured the swell of feminist artmaking across 15 countries that were at times upended by periods of dictatorial rule, civil war, and patriarchal tradition. With the acknowledgement that few of these artists explicitly identified as feminists, curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta set out to examine what they deemed the “political body” in terms of bodily autonomy and social convention in this survey, the first of its kind in the U.S.

A Few Words: Given the unprecedented nature of the exhibition, Contemporary Art Review LA wanted to see even more. “The unification of so many overlooked female artists from Latin America makes clear that this exhibition barely scratched the surface of the larger, worldwide exclusion of artists based on gender alone, leaving one with the sad realization that ‘Radical Women’ was just a drop in an ocean of omissions. Those untold stories can’t come soon enough.”

“Twenty Six Contemporary Women Artists,” 1971

Location: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

Featured Artworks: Mary Heilmann, Moonlight Sea, 1970. Sylvia Plimack Mangold, Shaded Corner, 1969. Merrill Wagner, December, 1970.

Why It Changed the Game: Curator Lucy R. Lippard pounded the pavement for this groundbreaking exhibition: Completing over 100 studio visits in six weeks, the resulting show of 26 emerging artists only included those who had never had a solo show, in attempt to bring each more attention. Lippard has acknowledged that, at the time, she was only just beginning to scratch the surface of the caliber of women artists within the East Coast scene.

A Few Words: For Lippard, this exhibition was personal: “I have recently become aware of my own previous reluctance to take women's work as seriously as men's, the result of a common conditioning from which we all suffer … The woman artist has tended to be seen either as another artist's wife, or girl, or as a dilettante. Now I know that, contrary to popular opinion, women are not any more ‘part-time artists’ than anyone else.”

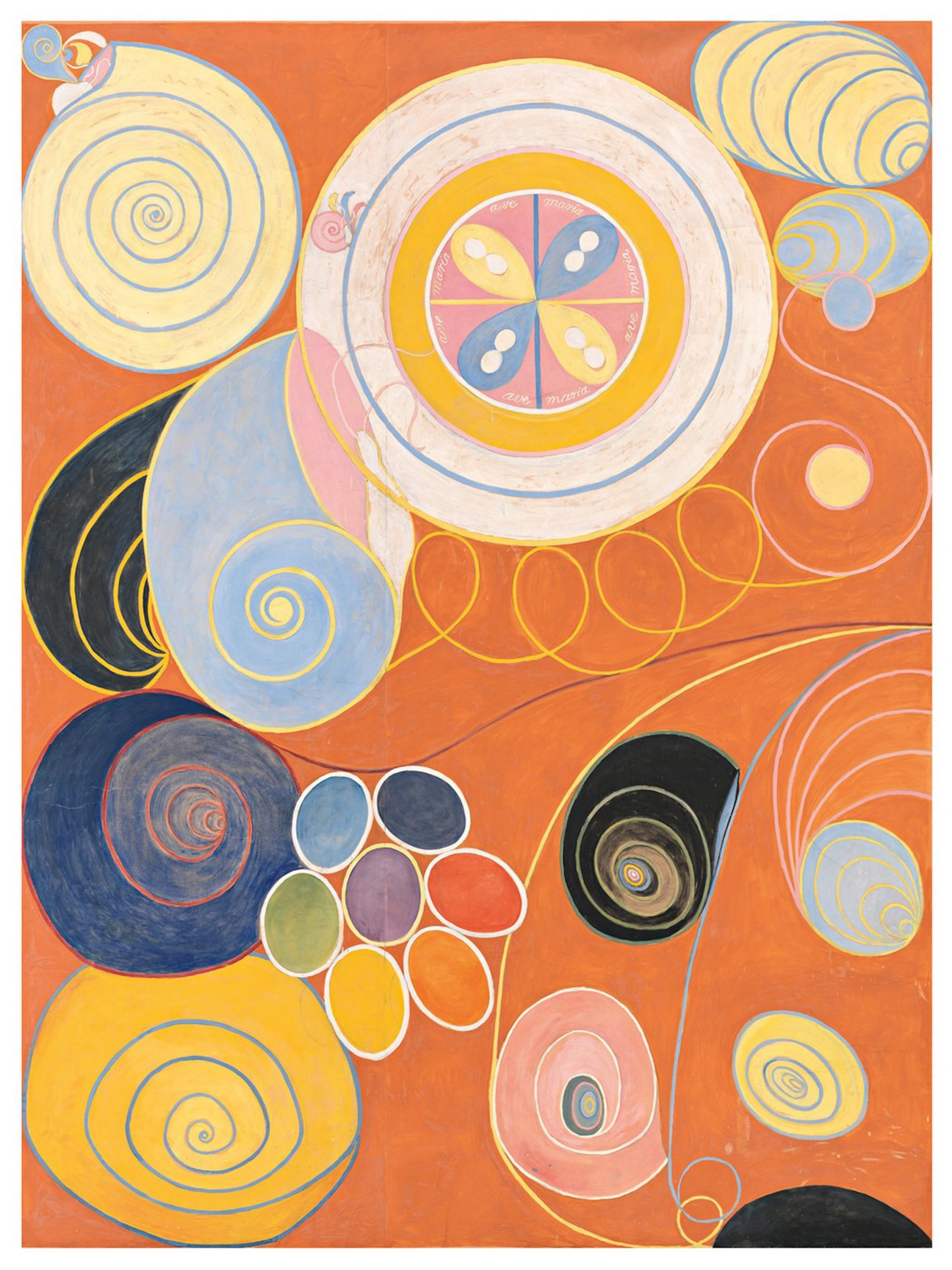

“Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future,” 2018

Location: The Guggenheim

Featured Artworks: “The Ten Largest” series, 1907. “The Primordial Chaos” series, 1906-07.

Why It Changed the Game: Few artists could be considered quite as “ahead of their time” as Hilma af Klint. The spiritualist and painter pioneered modernist abstraction over a decade before the likes of Wassily Kandisky and Piet Mondrian gained international attention for their work. Klint’s penchant for privacy meant that her paintings—staggering feats of saturated color and meticulous drafting—were rarely viewed during her lifetime and did not get real attention until the mid-1980s. The Guggenheim’s exhibition became the first major solo survey devoted to the artist, putting forth the radical notion that a woman had, in fact, done abstraction first.

A Few Words: The New York Times attested to the transportative effects of Klint’s work: “If you like to hallucinate but disdain the requisite stimulants, spend some time at the Guggenheim’s staggering exhibition.”

“The Quilts of Gee’s Bend,” 2002

Location: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Featured Artworks: Loretta Pettway, Lazy Gal, 1965. Leola Pettway, Log Cabin, 1975. Essie Bendolph Pettway, Roman Stripes variation, 1997.

Why It Changed the Game: Something was in the water in Gee’s Bend. The small, tight-knit Black community produced bold, color-blocked quilts that transmuted traditional “women’s work,” with many quilts hanging side by side often created by mothers and their daughters. “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” exhibited over 60 quilts by 42 different women from this small Alabama hamlet, crafting a story of both collaboration and individuality in this time-honed craft.

A Few Words: A traveling exhibition, “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” earned high praise in The New York Times when it came to the Whitney, with one reviewer citing the quilts as “some of the most miraculous works of art America has produced.”

“Exhibition by 31 Women,” 1943

Location: Art of This Century Gallery

Featured Artworks: Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940. Leonor Fini, The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes, 1941. Dorothea Tanning, Birthday, 1942.

Why It Changed the Game: In the male-dominated field of surrealist art, the inimitable Peggy Guggenheim sought to disrupt the status quo. At the behest of her friend Marcel Duchamp, the famed curator put together a lineup of female artists creating work in the surrealist tradition. The resulting show at the Art of This Century Gallery sparked reviews both praising the work and patronizing Guggenheim and the artists’ efforts. A critic for Art Digest wrote of the show: "Now that women are becoming serious about Surrealism, there is no telling where it will all end.”

A Few Words: Georgia O’Keefe declined to participate in the show, citing her refusal “to be categorized as a ‘woman painter,’” encompassing the rift the title caused at the time.