Everybody has a story to tell, but not all stories are worth reading. As a storyteller, Safiya Sinclair might be one of the more remarkable exceptions of our era to that rule. The former model and active poet possesses an ability to place us, her readers, in the moment—whether it be one of historical or personal record.

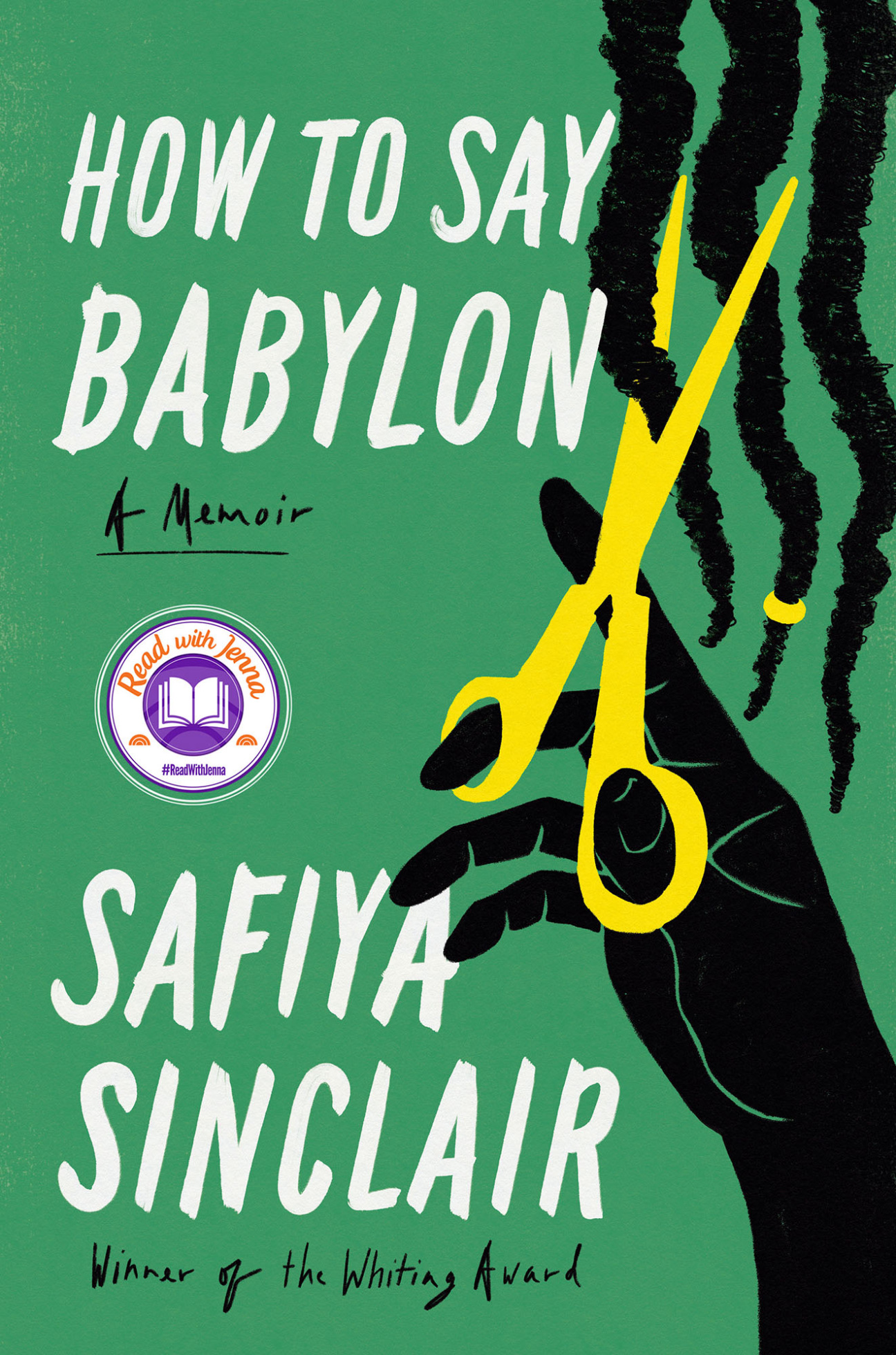

Late last fall, Sinclair followed up her debut poetry collection, 2016’s Cannibal, with How to Say Babylon, a memoir about her Rastafari upbringing that has been lauded and applauded by the likes of Barack Obama, Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, and more.

Sinclair grew up in Jamaica, under the watchful eye of her Rastafarian father, in an environment defined by its resistance to the colonialist gaze—but with the same obtuse and unbearable patriarchal constraints. At 18, Sinclair returned home from a modelling trip to the U.S. with pierced ears and faced the ire of her father. “My body was supposed to be Jah’s temple until it was my husband’s, and now I had defiled it,” she recalls in How to Say Babylon.

For Rastafari, biblical accounts of Jewish persecution sound like their own. “Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police who had pummeled and killed them. Babylon was the church that had damned them to hellfire. It was the state’s boot at the throat, the politician’s pistol in the gut. The Crown’s whip at the back. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of Western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people, and the corruption of Black minds. It was the threat of destruction that crept, even now, toward every Rasta family,” Sinclair says in her memoir.

The book is the coming-of-age story of a girl entering womanhood, finding her voice and her own body amid powerful gendered constraints. Rastafari, of course, can claim no exclusive ownership over the idea that men deserve better treatment than women.

However, given its origins as a liberatory force on an island that was “claimed”—first by the Spanish, who exterminated the native population in 1494, and then by successive waves of Europeans using African slaves, culminating in British rule from 1655 to 1962—Sinclair’s story is unique for its candor and critical perspective. “It's about Jamaican history. It's about Caribbean womanhood and Caribbean selfhood,” Sinclair offers over Zoom while touring the country to promote the book’s release.

Indeed, Jamaica has an international reputation and perception that belies its size, something the island owes largely to Reggae music, which is inextricably tied to Rastafarianism. The movement began as a call for liberation in the face of British colonial power. Inspired by Marcus Garvey, Leonard Percival Howell “looked toward Africa for the crowning of a Black King.” That king was Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, the only African nation never colonized.

Sinclair’s memoir opens with an account of Haile Selassie’s visit to Jamaica in April of 1966: “According to Rasta folklore, no visitor to Jamaica had ever received such a welcome; no dignitary or celebrity, not even Queen Elizabeth II, who had visited only a month before. Like a scorched wind out of Eden, seven white doves burst out from the clouds, and behind them emerged the first silvery tip of the airplane. The plane was white and bore a streak of red, gold, and green, with the roaring Lion of Judah insignia emblazoned in the middle. As the first glare of sunlight reflected off the emperor’s approaching plane, illuminating the entire Kingston sky, the rain instantly stopped and the tarmac at Palisadoes erupted in an ear-splitting roar of pandemonium.”

It’s the urge for a broader political reconciliation that tugs at our hearts while reading this book. Jamaica, in the popular imagination, often conjures images of white sandy beaches that, like most of the Caribbean, are packaged and sold as tourism.

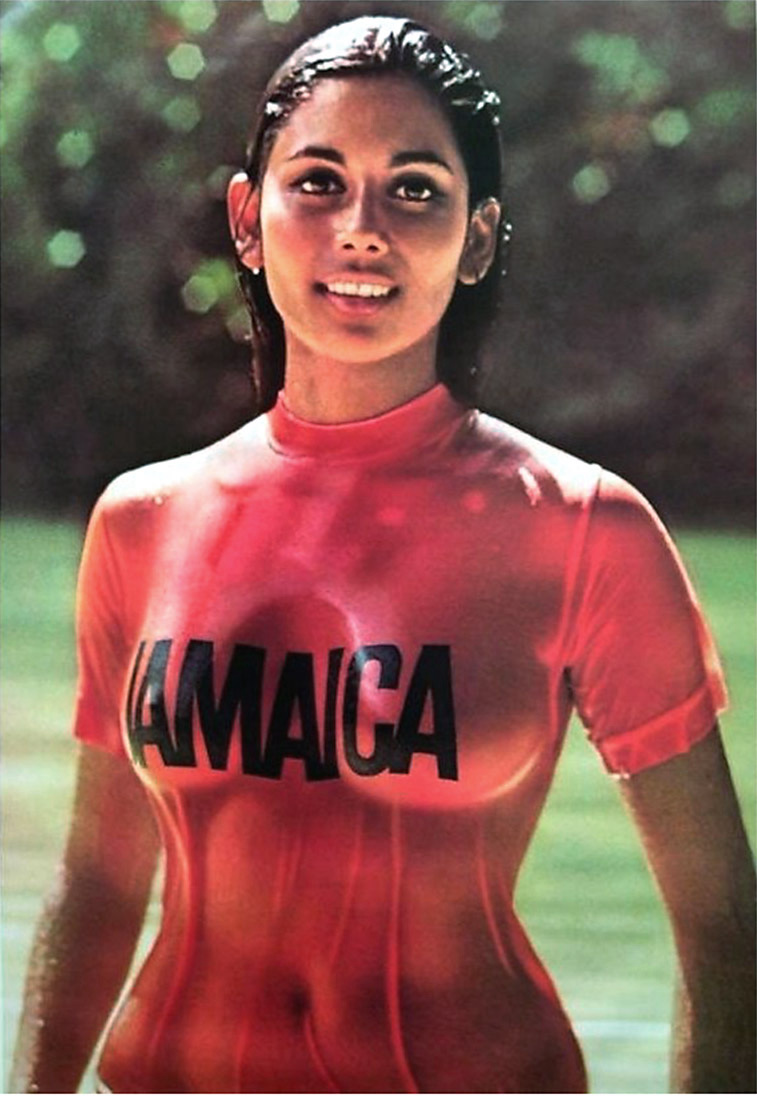

It also conjures Reggae music. If you grew up a Black boy in America in the 1970s, the sounds of reggae and surf might be accompanied by a vision of a beautiful woman in a tight red t-shirt—with ‘Jamaica’ scrawled across it in a simple font—emerging from the sea (in reality, her name was Sintra Bronte, and she was Trinidadian). With the exception of salacious tourism advertisements like this one, which appeared in magazines and made their way onto countless bedroom walls around the world at that time, women are rarely presented as the face of Jamaica.

“I began thinking about writing the book maybe 10 years ago, but I didn't think I was ready,” Sinclair continues. “It was too fresh, and I didn't want to write from such an immediate wound. The moment when I thought I could write the book is [mentioned] at the end: I returned home after a long time away, and I read my poem at the Calabash Literary Festival [in 2018]. I invited my father to come, and it was the first time he ever heard me read my poems.”

Writing about such heavy things—personally, culturally, and nationally—certainly didn’t come easily to Sinclair. She was 34 at the time and had been writing poetry since the age of 10, publishing her first piece in her home country’s national newspaper at 16. “Poetry was the voice I had forged because for so long I had been voiceless,” she writes in the book.

This was a side of Sinclair’s life that she decided could no longer be kept separate from her father. “After having this complicated relationship that I explore in the book,” she recalls over Zoom, “I said to my father, ‘I just want you to hear me.’ After I read the poem and got off the stage, he hugged me and said, ‘I'm listening. And I hear you.’ That was the specific moment when I realized I was ready to write.”

in your life?

in your life?