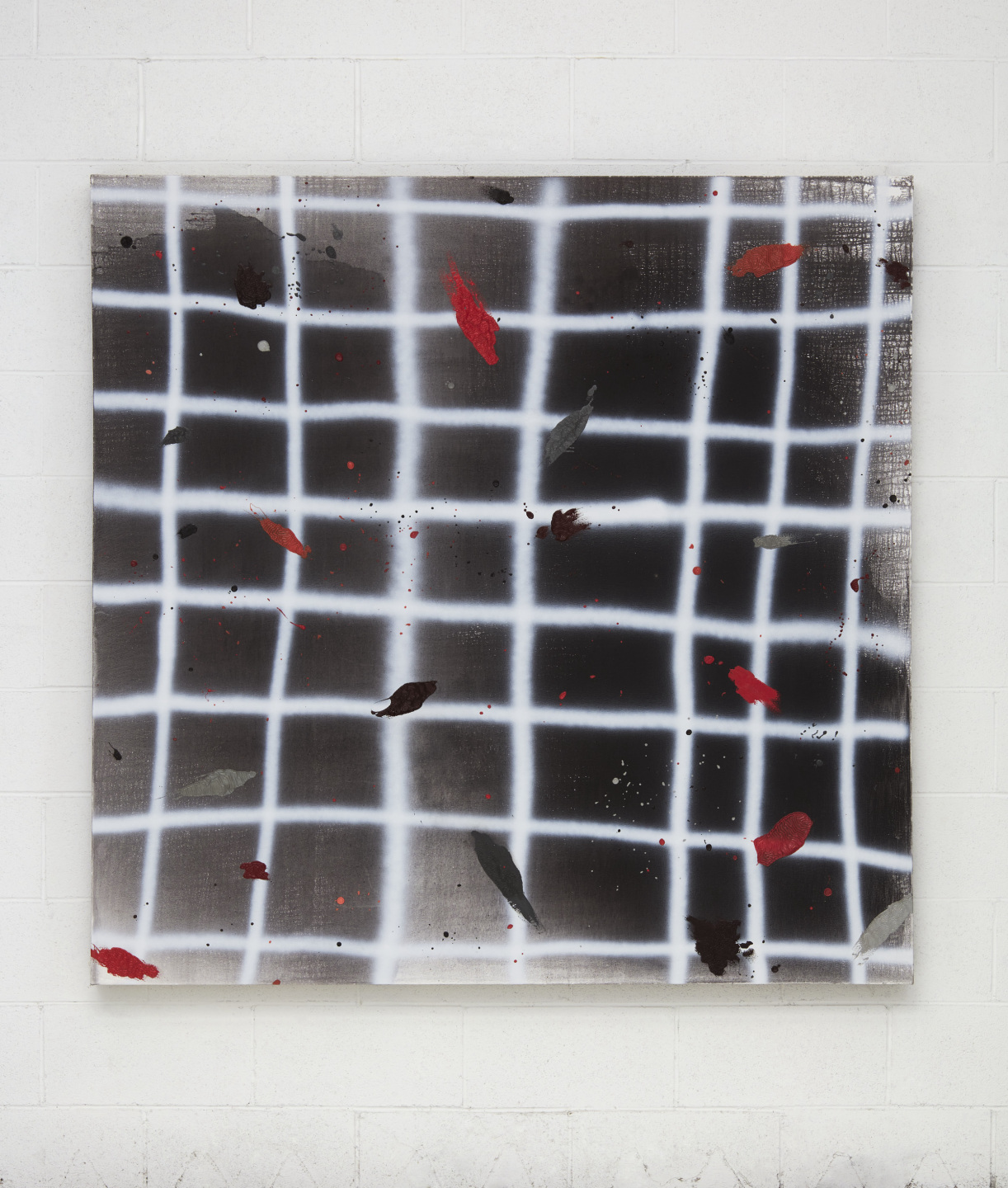

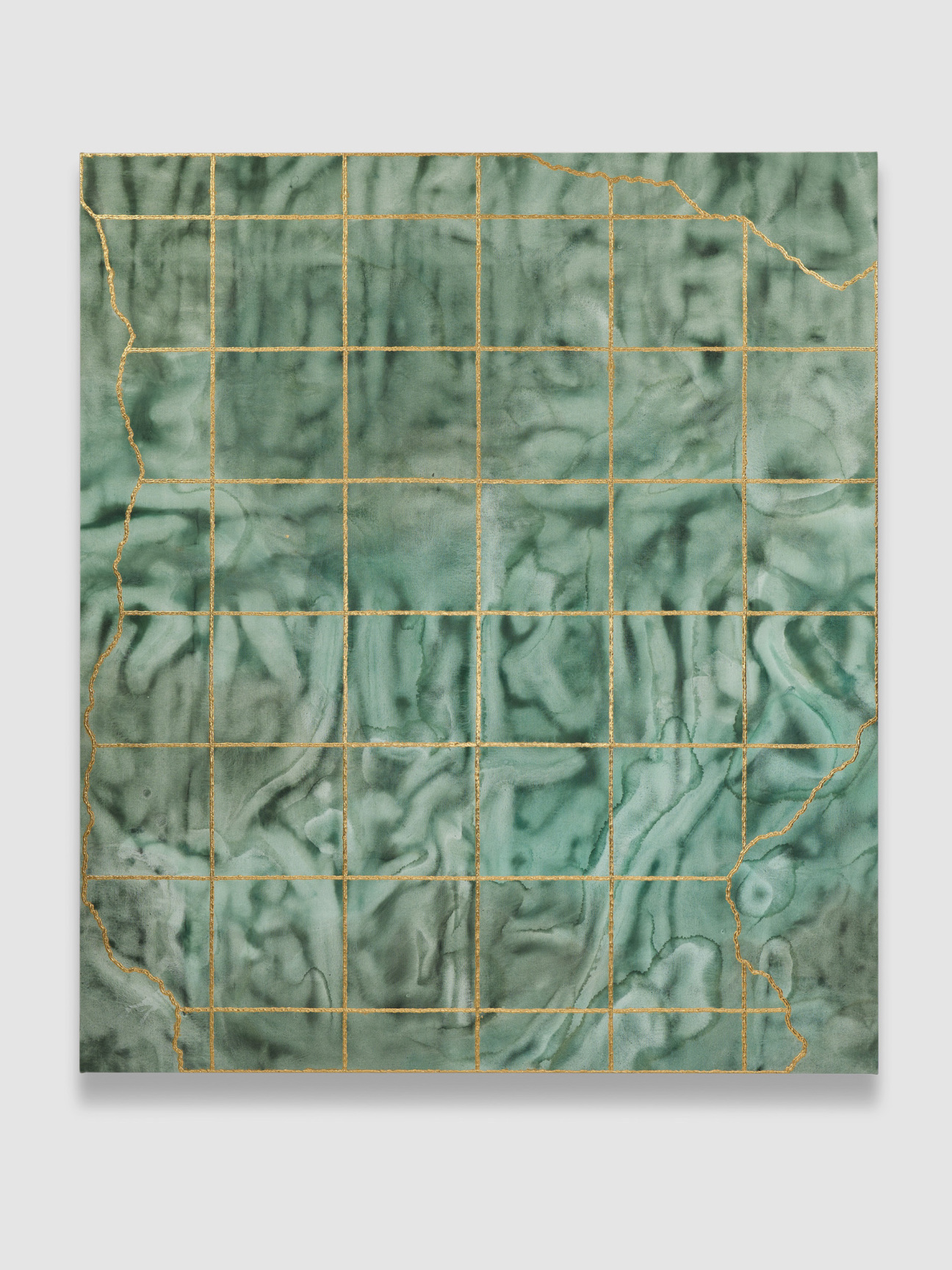

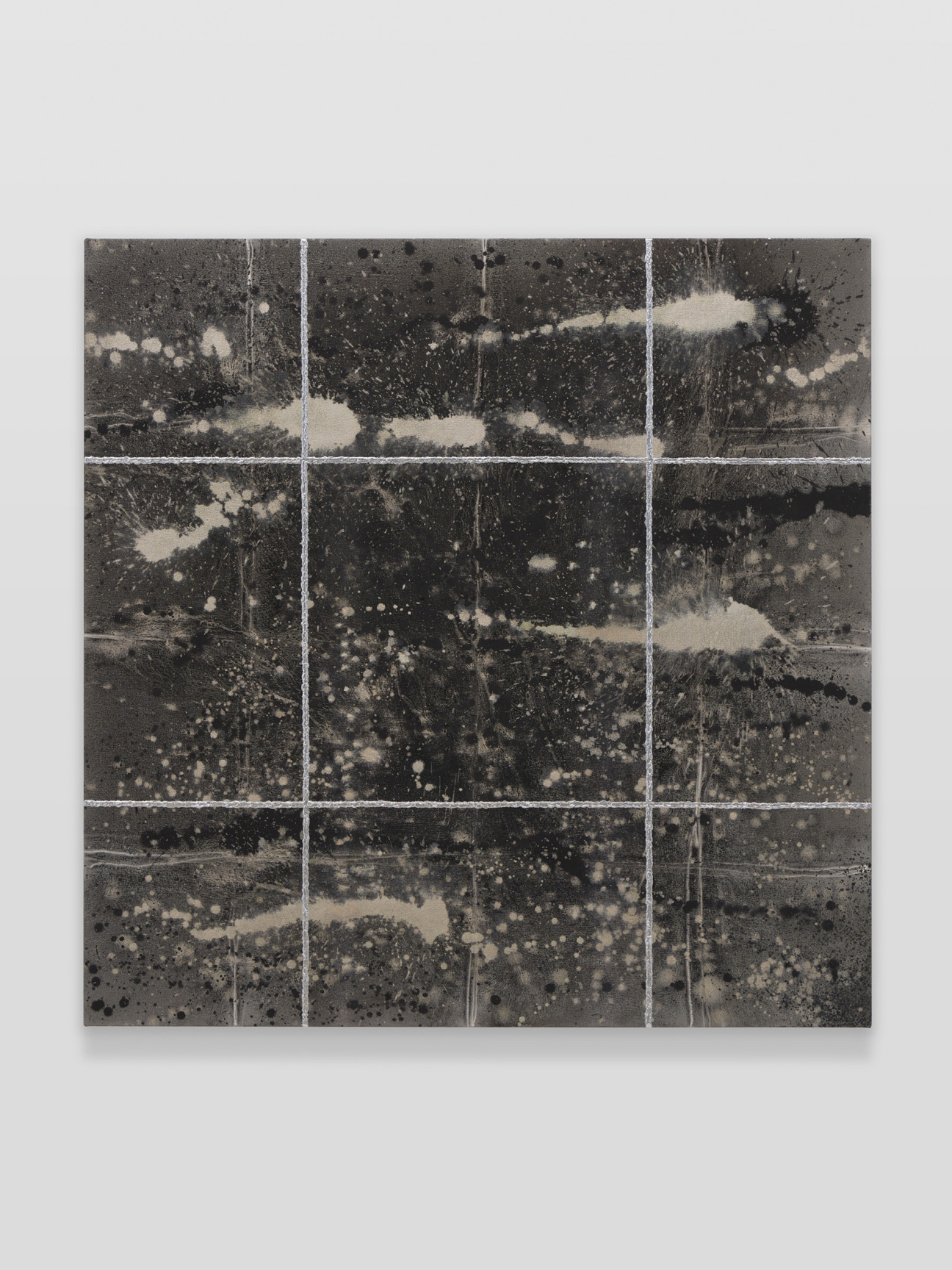

Rebecca Morris never wanted a conventional survey show, with its chronological march through 21 years of output. So she opted for something else entirely. “Rebecca Morris: 2001-2022,” which opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago on Sep. 30, is a loping narrative of color, blobs, zigzags, metallic spray paint impasto, and Morris’s signature lobster claw motif.

To walk through it is to hopscotch through a career that has persistently charted new territory for abstract painting, fusing errant drips and shoeprints with rigorous technique and structural composition. Worth traveling for, it is a big, bold chromatic show that epitomizes her famous 2004 Artforum manifesto, where, among other bon mots, Morris declared in all caps—what could be the title of this exhibition—“ABSTRACTION FOREVER!”

When MCA Chicago curator Jamillah James invited Morris to collaborate on the venture, the Honolulu-born, Los Angeles-based artist was hesitant. Hanging a 27-painting show year-by-year felt inauthentic given the cross-pollination Morris experiences making her work. “One of the things I kept thinking about was how to take this opportunity and make it something that was really useful to me as an artist,” she explained on a walkthrough of the show’s initial outing at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, last fall. “What can I get out of this? Seeing it chronologically—I know that. I wanted to see what a painting from 2002 looks like next to something from 2010.”

At the same time, Morris kept the viewer’s experience in mind. The format aims, she said, “to make it so you’re thinking about the paintings themselves, and the possible relationship between paintings becomes a more complex, interesting way to look at the work.”

In 2018, I visited Morris’s Los Angeles studio to preview works-in-progress for “Rebecca Morris: The Ache of Bright,” a solo exhibition at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston. On a custom scaffold, Morris hovered above the floor to direct pigment across a large-scale, unstretched canvas.

In addition to her marks, the surface captured incidental dirt smudges and splatter from other paintings—not to mention her own footprints, a facet of her practice that’s always seduced me (yes, that may be the trace of a Converse All Star among seemingly disassociated gestures). “I have to be careful frankly about what shoes I wear because certain treads are very representational, like a Birkenstock,” she explained.

Like Wassily Kandinsky and Lee Krasner, Morris’s work expresses the tension between deliberation and chance. The shoe prints are “about another form of patina and about a body walking on the surface. It’s part of the transition of all these paintings being made on the floor, and then going up on the wall, which is actually pretty major,” said Morris. “A lot of abstraction embraces accident. I’m trying to catch and capture the accidents.”

The show’s nontraditional format has offered her new insight into her old patterns. “I’ve been very aware that I have avoided the color blue,” said Morris. “It’s not that I haven’t put in anywhere, but I've avoided making a painting whose primary thrust was, ‘I’m a blue painting.’ It’s just such a representation color. When somebody goes to blue, they think water; they think sky.” She paused for a beat, then added wryly, “Also as a child, I had a lot of dark blue. I always had a million dark blue sweaters. I had dark blue coverlets. It was a color I kind of had enough of.”

We reconvened ten months later, on the occasion of her show of new work at Bortolami Gallery in Tribeca. It’s a salient return after her first exhibition with the gallery was shuttered amid New York’s March 2020 lockdown (it reopened with safety precautions later that summer).

True to form, Morris seized upon the opportunity to learn from her own oeuvre: observations crystallized upon seeing her exhibition at the ICA LA. Studying the survey, she asked herself: “What have I done? What haven’t I done? Where are the gaps? And are those gaps places I want to make new works from?” Of note, her Bortolami show contains two large “blue paintings”—all saturated, piercing glory—not a hint of seascape in sight.

“Those paintings are made within a timeframe of a year, but have a wide range of stylistic possibilities in a single period of work,” she told me. Indeed, the new work harkens another of her original Artforum proclamations: “Make work that is so secret, so fantastic, so dramatically old school/new school that it looks like it was found in a shed, locked up since the 1940s.”

Ultimately, it is this willingness to push herself that lends Morris such enduring gravitas and places her squarely among contemporaries like Julie Mehretu, Cecily Brown, and Charline von Heyl, even if the art market doesn’t recognize it yet. Institutions and critics have taken note; Morris is the kind of abstract painter that only comes along a handful of times a generation.

“Rebecca Morris: 2001-2022” is on view at the MCA Chicago through April 7, 2024. “Rebecca Morris: #31” is on view at Bortolami in New York through November 4, 2023.

in your life?

in your life?