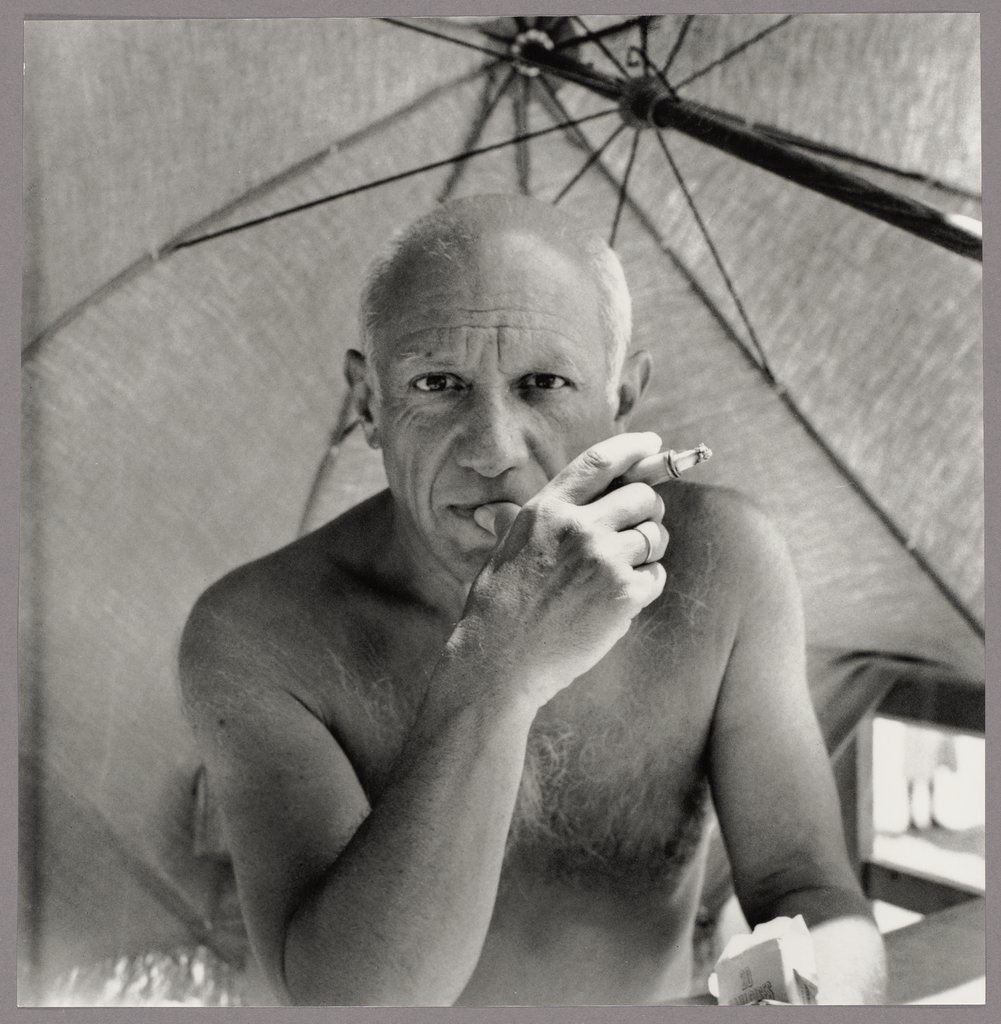

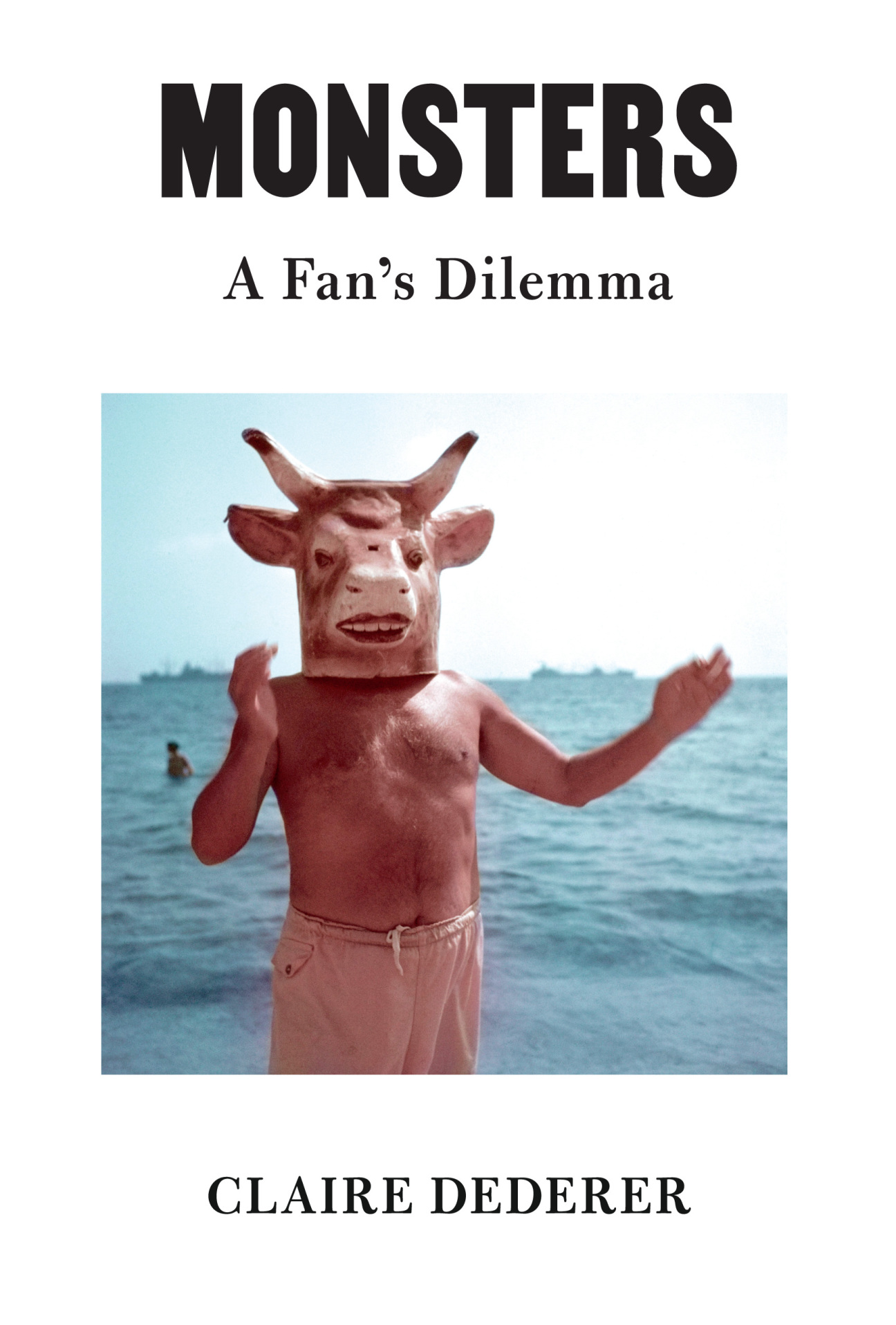

Celebrating Pablo Picasso’s legacy has become a precarious mixture of compromise and dubious admiration. How can a woman, or anyone for that matter, hang a painting or print on their wall crafted by a man who once unabashedly told his lover that “women are machines for suffering”? In 2017, as the raging fire of the #MeToo movement consumed contemporary and past icons alike, many were left holding the remnants of art and media they once loved, or still did. Claire Dederer, author of books including Love & Trouble and Poser, became a prominent voice in the conversation with her Paris Review essay, What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men? The piece began with the question that many found themselves facing: can we separate the artist from the art? What followed was a candid account of moral confusion and the inherent selfishness required of any artist. For every question Dederer sought to answer, she raised another. Now that the embers of that fervent period have had time to cool, she is launching her latest book, Monsters: A Fan's Dilemma, a full-length investigation into the topic. On the first page, she confronts the monster who most haunts her, Roman Polanski. In the latter half of the book, she interrogates herself. Today, however, ahead of the 50th anniversary of his death, the pressing matter is: what do we do with Picasso?

CULTURED: Picasso was mentioned in the first lines of your Paris Review piece. What do you make of him as an artist, and as a man? Why did he stand out?

Claire Dederer: One of the main threads in the book wrangles with the idea of genius. The genius isn’t so much a kind of person as he is a status of person—that is, a person who gets to do whatever he wants. Picasso embodied that idea, but he also shaped it. He was one of the first great artists of the mass communication era, and he came to stand for the very idea of genius. The genius is moved by artistic impulses. He’s channeling something greater than himself. We value that artistic impulse hugely, and we tend (or have tended) to forgive darker impulses that come along with it. We’re even thrilled by those darker impulses. Picasso’s freedom was absolute: in his art, in his behavior. Genius gets a hall pass.

CULTURED: Is there something different about a monstrous artist long gone, rather than one who is still with us?

Dederer: An artist from history affects us differently in a couple ways. For starters, our economic boycotts don’t affect him (or her)—just the estate. But also: we tend to be gentler with monstrous artists from history because we tell ourselves that they didn’t know better. That’s one of the ideas my book pushes back against—the idea that we’re somehow better now, that we’ve reached some kind of benign place in history.

CULTURED: When anniversaries like this one come about, and the work of a monstrous genius inevitably gets dragged back into the spotlight, how much space on the gallery wall do we reserve for an explanation of, or apology for, what they’ve done?

Dederer: I personally appreciate the more overtly political age of museum curation we’ve entered. I love to see a museum wrestle with an artist’s biography in a transparent way—or with a collector’s legacy, or with the museum’s own complicity. That kind of commentary lays bare the interior conflict we’re all experiencing. It trusts the viewer to come to their own conclusion about whether or not the biography of the artist fatally disrupts the experience of the work.

CULTURED: Picasso’s work is a direct product of his relationship with women. Is there a difference between that kind of art, and work that is simply made by a questionable individual? Is it even possible to distinguish the two?

Dederer: Hmmm, do you mean work that takes underage women in a sexual setting as its subjects? Do you mean work that depicts women the artist himself has abused? In any case, I think Picasso’s domination of women is deeply tied to his identity as both person and artist. The genius, after all, is master of everything that crosses his path. He’s only subject to one thing: his genius.

CULUTRED: What prompted you to expand your essay into a full-length book?

Dederer: The essay was always intended as the first chapter of a book. I actually had the idea to write a book about monsters of art in 2015 or so. It grew out of my fascination with Roman Polanski, who was a figure in my previous book. I spent the next year exploring this question: What do we do with the art of monstrous men? When #MeToo exploded at the end of 2017, I couldn’t bear to not be part of the conversation, and happily The Paris Review published what was then the first chapter. I think one of the reasons the essay connected with readers was because it wasn’t a hot take. It was a long-simmering take.

CULTURED: Your essay poses a number of questions. Have you been able to find any answers in the years since? Can readers expect to find them in your book?

Dederer: I do come to quite a few conclusions, but readers who are looking for rigid guidance will be disappointed by the book. One of the main ideas I explore has to do with the importance of subjectivity to the audience’s experience. Each response is shaped not just by the biography of the artist, but by the biography of the audience member. There is no authority out there that’s going to solve these problems for you.

CULTURED: When covering an issue so divided in opinion along the gender line, do you consider whether you are writing for women? For men? For yourself? Can you do it all at the same time?

Dederer: I did worry about this at first. There were dark days in the first couple of years of writing the book where I read what I had written—which was deeply ambivalent and therefore nuanced—and worried that I was trying to appease both/all sides. I was worried that I was writing out of fear. But I realized that I was writing the truth of my own response, and I had to assume the good faith of the reader. I went through the book and poked every sentence to make sure it was really what I thought was true—and I kept going.

CULTURED: The cultural moment in which you released your article has since evolved. What do you think of the landscape into which you are releasing this book?

Dederer: I’ve had several people comment that they’re happy the book is coming out now, because people are more receptive to nuance on this subject. I’m not sure. I look at Twitter and it seems more savage than ever. But here’s what I do know: the pandemic, and the massive forest fires on the West Coast, and the George Floyd protests all worked together to radicalize me, as they radicalized many people. I’m a different person, politically, than I was when I started the book. And I’m so grateful I had time to grow into these new thoughts and let them shape the book.

CULTURED: You've written about the selfishness required to finish a book. Now, do you feel any more monstrous?

Dederer: Are monsters this exhausted? The main thing I feel is completely worn out by the book. And I’ve developed a serious case of sitzfleisch.

in your life?

in your life?