When fear ferments long enough, it turns into activism, producing some of the world’s most arresting and necessary art. If we turn to the history of contemporary works by female artists, we find a record of protest, rallying-cries, and subversive exploration. As women's rights over their voices, bodies, and autonomy are increasingly threatened, these artists have set themselves and their successors on the course of righteous indignation.

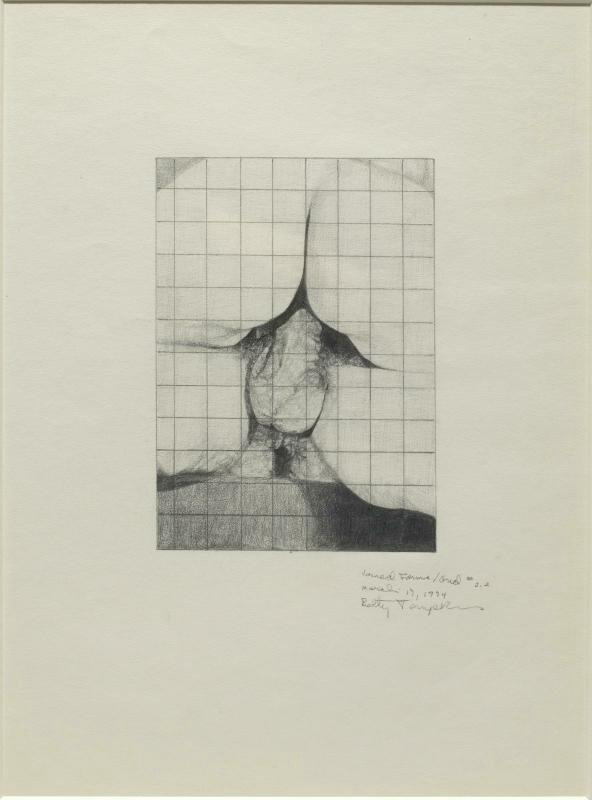

Betty Tompkins Likes to “Get in Trouble”

“The only way you'll make it in New York is on your back.” This was the demoralizing response Betty Tompkins received from a college professor after she told him she was moving to the Big Apple to become an artist. Instead of sinking into her shell, Tompkins set out to prove him wrong. Her explicitly raunchy "Fuck Paintings" from the late 1960s and early '70s brought conversations around sex—and women’s agency—into the open. Though the works were flagged by French customs officials in 1969 and subsequently denied display, the first of the series, Fuck Painting. (Joined Forms/Grid), 1973, is now held in the esteemed collection of the Centre Pompidou. As Tompkins told Martha Wilson in an interview for CULTURED, “Thank god.”

Laurie Simmons Blurs the Lines Between Childhood Innocence and Adulthood

Unpacking the many gendered connotations of the doll—be it the Barbie doll, the subservient wife, or the sex doll—has been a 50-year project for feminist heavyweight Laurie Simmons, and if her latest series of work proves anything, it’s that there’s still more to be done. A reconfiguration of an earlier series of photography works from 2007-09, Simmons’s inventive “Color Pictures/Deep Photos 2007–2022" features cut-out photographs of women posing provocatively, paired next to miniature dollhouse furniture and men who gaze at them possessively. These are the unfiltered realities of our sexist world, Simmons asserts.

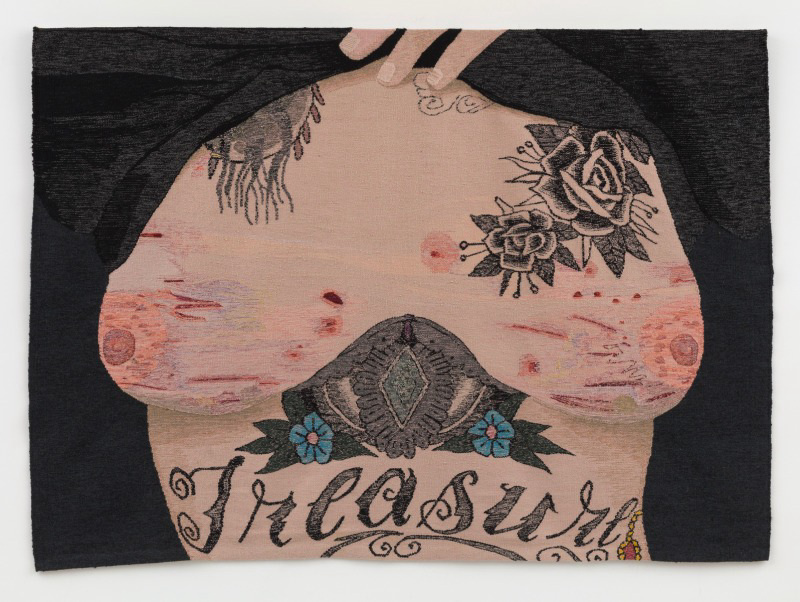

Erin M. Riley’s Tapestries Confront the Anxieties of Womanhood

Last year, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut revisited its 1971 exhibition of all-women artists—the first of its kind in the U.S.—putting a contemporary spin on the seminal exhibition. Among the artists included in “52 Artists: A Feminist Milestone” was maverick Erin M. Riley. As a fiber artist, Riley weaves her worries into tapestries, working through her trauma one stitch at a time. The Massachusetts-born artist’s anxiety-filled works from the Covid-era illuminate her struggles with dermatillomania—a skin-picking disorder—and catalog her search for personal identity in a perilous moment for American women.

Dindga McCannon’s Swirling Works Honor Black Heroines Big and Small

Dindga McCannon is 75 and proud. Her bold and prolific career spans costume design, mural art, print-making, textile assemblage, and illustration. A Black woman raised in Harlem and the Bronx, McCannon wasn’t granted a solo exhibition until she had five decades of art-making to display. Her assertive, whimsical, and soul-warming works from “In Plain Sight,” a 2021 solo show at Fridman Gallery, honor both well-known and overlooked Black heroines—from a red-heeled Harlem street-goer to one of the earliest Black female flight attendants. McCannon unites women’s histories through a vibrant visual language sewed into mixed-media quilts and painted onto canvases whose warm color palettes draw viewers into another world.

Leonora Carrington Imagined an Apocalyptic World

For the late Surrealist British painter, the symbol of the egg—a quintessential motif representing new life—was a fixation ripe for creative exploration. In 1970, Carrington wrote an apocalyptic play called Opus Siniestrus about the last woman on Earth gaining possession of the only remaining egg, her only hope for female futurity. Inspired by the text, Gallery Wendi Norris showcased the visual manifestations of Leonora Carrington’s imagined dystopia in a 2019 exhibition, featuring paintings and sculptures born out of “a world ravaged by patriarchal systems of violence, war, and ecological destruction,” as gallery director Matea Fish told CULTURED.

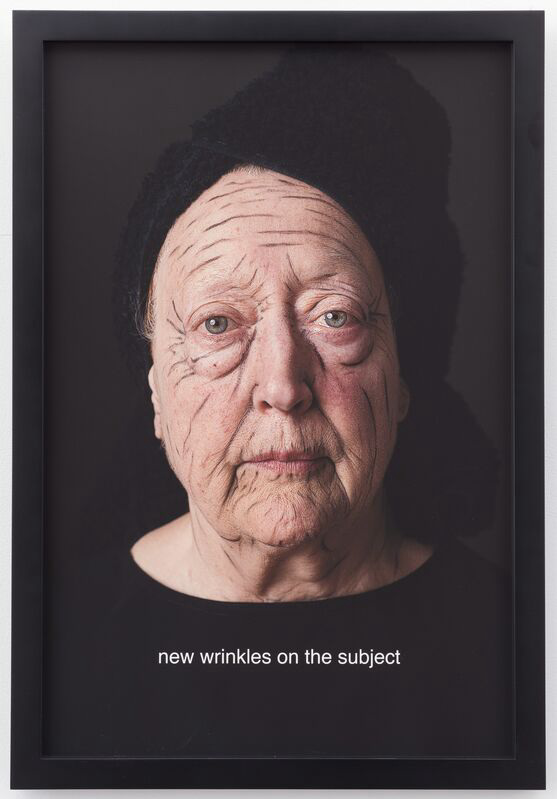

Martha Wilson Has "Fun Being an Old Lady"

“Artists work with what they have,” Martha Wilson told CULTURED in 2020, and at the time of the interview, the artist was (and still is) unabashed about her acceptance of aging as a woman. Wilson’s recent work unpacks the countless taboos surrounding this journey using none other than the artist’s own body as the focal material. In New wrinkles on the subject, a self-portrait from 2014, dark lines of makeup pronounce Wilson’s facial markings, reminding us how rarely women bear an unconcealed face—without inhibition—to the world.

Jessica Stoller’s Porcelain Displays of Excess Critique Hyper-Femininity

A pierced purple porcelain nipple, bearing a silver hoop fashioned in the shape of a bow. A female skeleton milking a sagging breast carrying a man’s head in a picnic basket. Feasts of food and flowers littered with maggots, snails, and armless hands. These sinister, often simply strange, sculptures—all hand-built out of porcelain—are Jessica Stoller’s wry way of critiquing female gender norms. As the artist told CULTURED, “in my tableaux, the female body oozes together with nature, change, life, and death in resplendent complexity.”

Senga Nengudi’s Experimental Sculptures Defy Artistic Conventions

Certain sights are hard to forget, and pantyhose out of context—stretched to their limits, filled with sand, and adhered to a museum’s white wall—happen to be one of them. "My purpose is to create an experience that will vibrate with the connecting thread," wrote Senga Nengudi in a 1995 statement. The artist has defied formal conventions for five decades, using unconventional materials in innovative ways to emulate the societal strictures placed on female bodies. Her winning of the Nasher Sculpture Center's 2023 Nasher Prize is just one reminder of the legend's continuing relevance.

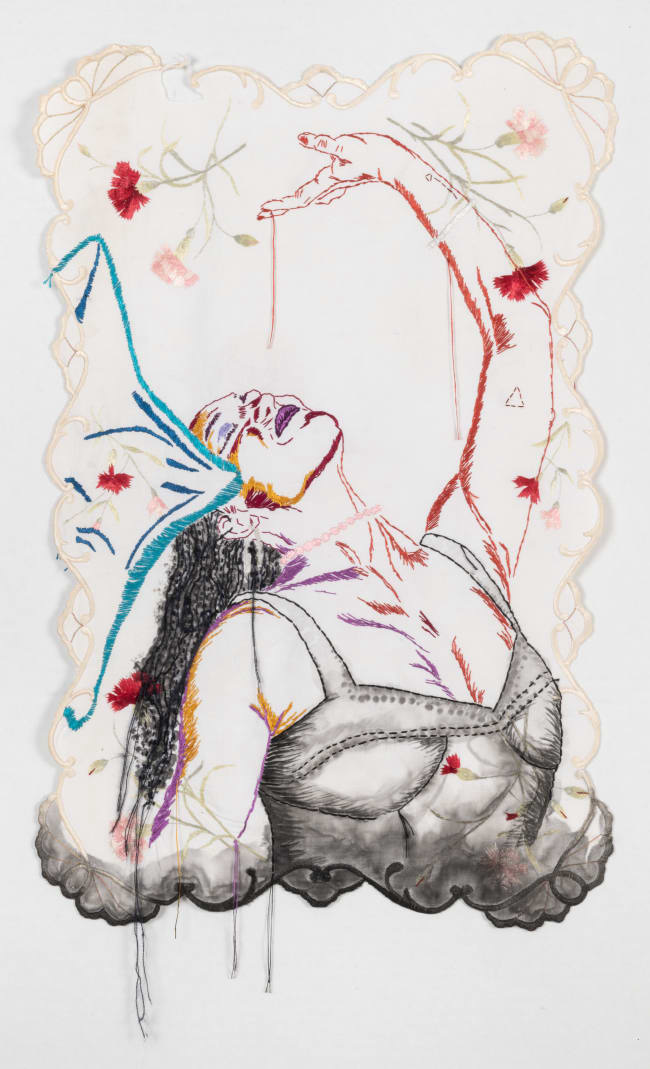

Zoe Buckman Sews the Sexism She Can’t “Unsee” into Lingerie

The oft-overlooked strength of female survivors—whether victims of gender-based violence, domestic abuse, or physical hardships like miscarriages or breast cancer—is foregrounded in Zoe Buckman’s BLOODWORK series, a collection of embroidered vintage textiles featuring rejoicing women, biting rallying cries, and portraits of female power. “We are either put on a pedestal as your mother, your queen, your wifey,” the artist told CULTURED in an interview from the pre-Trump era. “It’s either mother/goddess or dirty slut.” Indeed, Buckman succeeds in subverting this narrative; her subjects exude freedom and their full humanity shines.

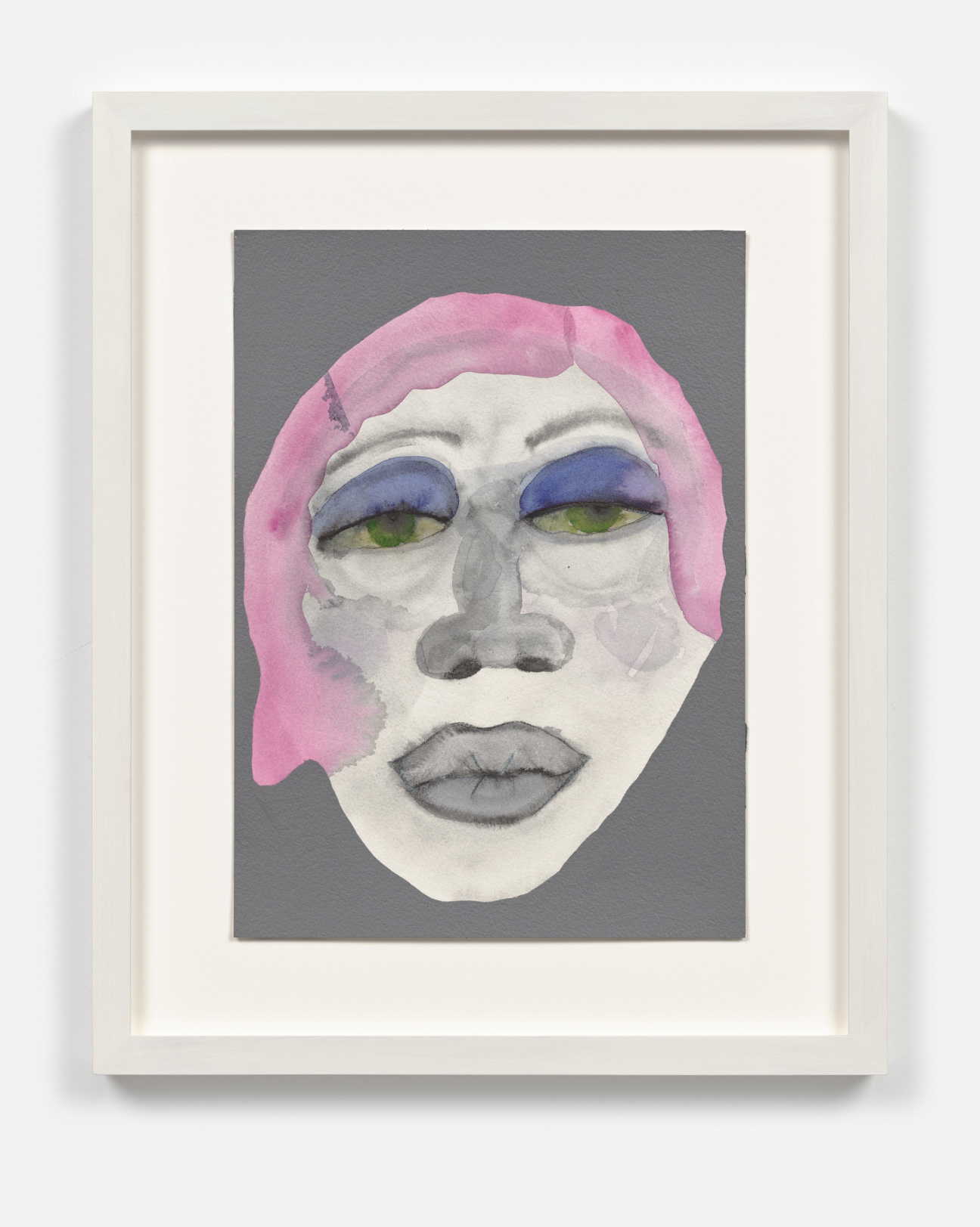

February James’s Sitters Feel and Reflect the Oppressive World Around them

In this climate-changing, post-Roe world, eco-feminist perspectives are more relevant than ever. Last fall, a group show at Berlin’s Galerie Max Hetzler titled “Bodyland” took on this complicated topic, and the self-described autodidact February James was a standout among the group of female artists included. Echoing Marlene Dumas’s loose handling of watercolor, James’s What it cannot own, 2022, is both a tribute and a eulogy to her sitter. The woman’s tired eyes are painted in a sad, hazy green—reflections, perhaps, of the exploitation that envelopes her.

in your life?

in your life?