If you had to choose one shoddily reproduced work of art from the dusty window display of your neighborhood thrift shop, your shrewdest pick would undoubtedly be The Kiss, 1907-08, Gustav Klimt’s gilded masterpiece. The sensual image of two lovers intertwined in an envy-inspiring embrace is now so ubiquitous—hung in dorm rooms and hotel lobbies, printed on toilet seats and lingerie sets—that its magnificence has been trivialized. The rebellious life of its Austrian symbolist painter has likewise been overshadowed by the image’s commercial success, an amusing thought given the free-spirited philanderer’s provocative bent.

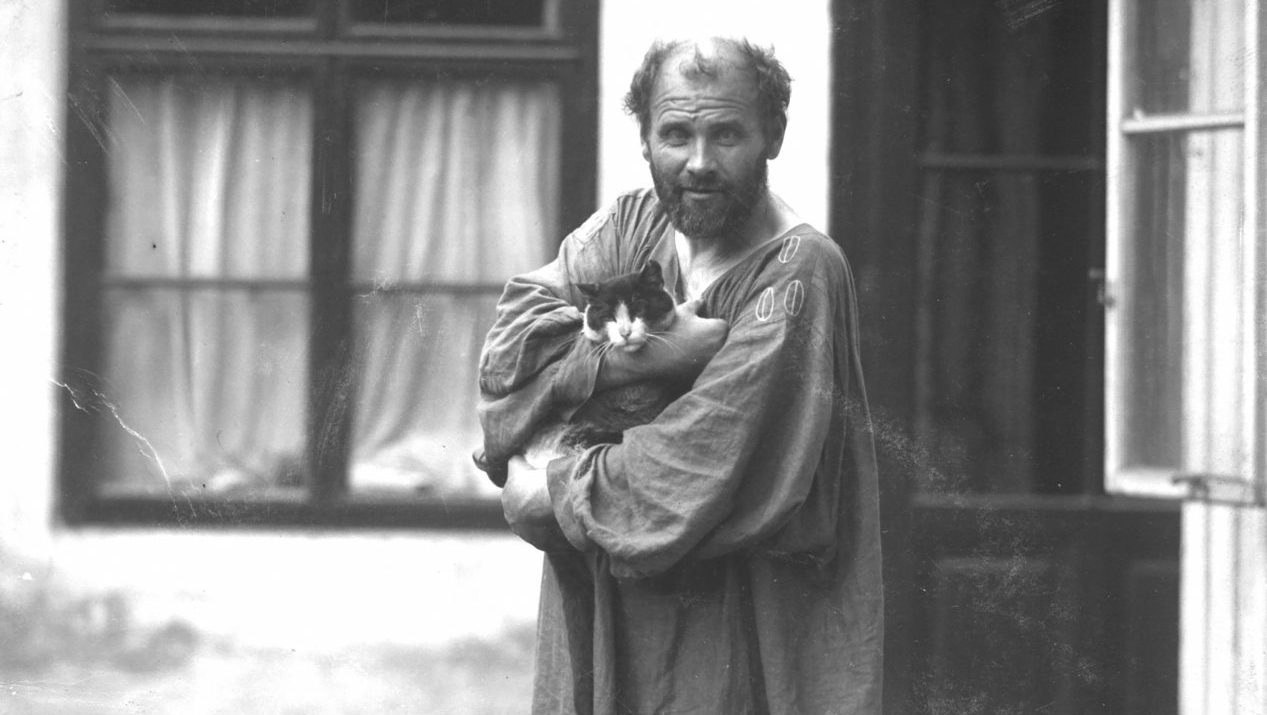

Standing in stark contrast to his most celebrated works—dazzling, gold-leafed Art Nouveau portraits such as Lady with a Fan, 1918, and Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901, each refined and exotic—Klimt was an eccentric whose erotic drawings and shameless disposition left his detractors reeling. Father to an alleged 14 children, sexual partner to innumerable female muses, and keeper of a great number of cats (whose bodily fluids made their way into his work), Klimt—who once claimed “there is nothing special about me”—was far more radical than he let on.

Born into poverty in 1862 on the outskirts of Vienna, the painter rejected the status quo in every facet of life, favoring artistic freedom over commercial success, sexual liberation over marital commitment, and unabashed self-expression over conformity. Ironically, given his post-mortem reputation, he was a founding member and early president of the reformist Vienna Secession movement, which prided itself on championing artistic liberty over the commercial viability of art.

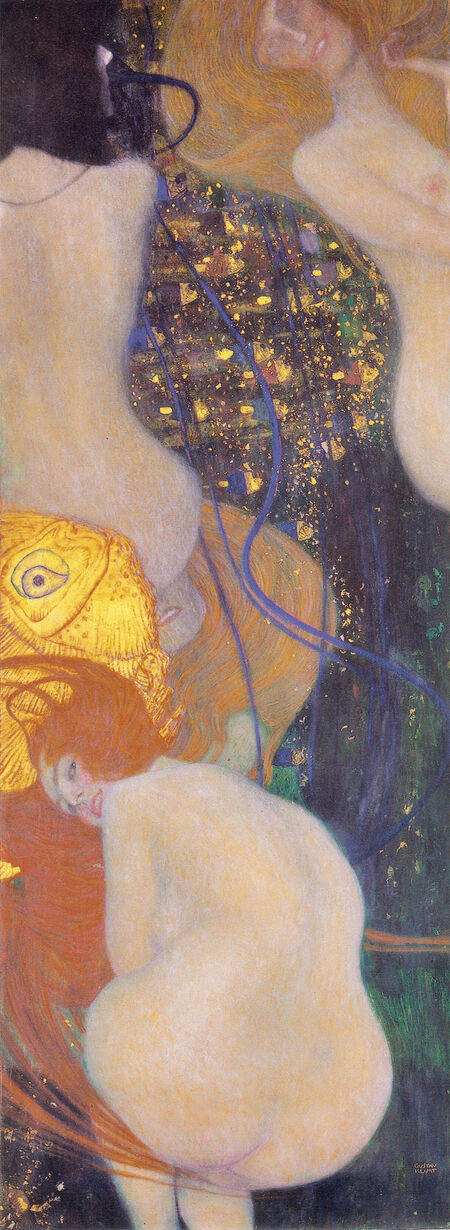

Commissioned by the Austrian Ministry in 1894 to paint an intricate series of ceiling murals in the University of Vienna’s Great Hall, Klimt seized a rare chance to publicly display his own sexual ideals. At the long-awaited unveiling, visitors gaped at the reveal of the massive compositions. Klimt’s mural Medicine featured a number of nude figures, their pubic hair on view to those standing below. “Perverted excess!” visitors cried. Klimt, never one to succumb, opted to leave his commissioners with a parting gift: a painting titled To My Detractors (its title was later changed to Goldfish) featuring a naked woman exposing her rear to the viewer with a sly look on her face. Needless to say, Klimt’s murals were never publicly displayed at the university.

In his personal life, Klimt was no less unabashed. According to accounts from friends and aides, the artist wandered around wearing nothing but an oversized smock, fell into bed with the many muses depicted in his portraits, and used cat urine as a fixative, much to the chagrin of preservationists. Though he had a lifelong partnership with the designer Emilie Louise Flöge, the two were never married. "If the families of the girls and women of the high society [only] knew under what conditions he carries out their portraits," said Sonja Knips after posing for the painter.

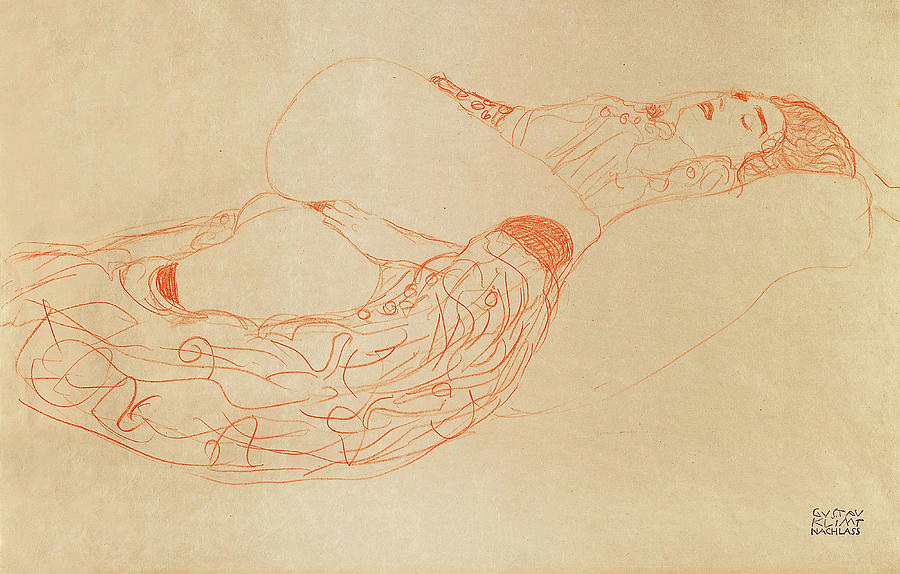

Indeed, the artist's eye developed in tandem with his sexual appetite. In the privacy of his studio, Klimt drew countless erotic illustrations which grew increasingly raunchy as the artist matured. Though he kept most of the drawings private, in 1907 he published Dialogues of the Courtesans, an illustrated edition of Lucian’s ancient texts accompanied by 15 titillating line drawings. Masturbating women, drawn in quick orange swirls to convey the ecstasy of their pleasure, were among the infinite sexual fantasies—or lived realities—Klimt committed to paper.

Today, Klimt’s works continue to be objects of scandal, though of a much different order. In the past three years alone, his paintings have been the subject of restitution cases, unsolved heists, clandestine possessions, and climate activism-inspired defacement. Meanwhile, the Klimt commercialization craze grows as his works are plastered onto face masks and projected through AI-generated digital pixels into dizzyingly immersive installations. Despite his status as an enfant terrible in life, Klimt's legacy is arguably stranger than the man himself.

in your life?

in your life?