Curator Anjuli Nanda Diamond has spent more than a decade working for the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation and their New York exhibition space, The 8th Floor, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she had a moment to sit with the work she’d done. A legacy project to make the foundation’s first book threw her back into the archives and the collection she’s help create. Here, Diamond tells us why An Incomplete Archive of Activist Art and the associated exhibition was an act of catharsis.

Kat Herriman: How do you distill six years of work into a book?

Anjuli Nanda Diamond: From a practical standpoint, there were always two aspects to the books. That's why it resulted in two volumes. There is the visual artistic expression side, the exhibitions and the formation of the Rubins' “Art and Social Justice” collection. Then there is the other side of the Foundation's activities, which are really community-based and about fostering nonprofits and artist-led initiatives in New York City. It was a way of looking at these two parts of the foundation's activities and celebrating them in a distinct way from each other, but also together.

Part of the impetus and drive of this book is that it is a collective effort. It's not the Foundation celebrating their interactions with all of these seemingly disparate parts but how they all overlap and support each other.

KH: Was the editing process cathartic?

AND: Absolutely. It was an almost a reassuring process because with each show there's a little bit of tunnel vision that happens when you're looking at it. To step back and look at everything in concert with each other is not necessarily an exercise that curators engage in very often. It was somehow exciting to look back at the installation shots and to see how the individual works interacted with each other. Then looking at them sequentially, page after page within the volume, and seeing how they speak to each other across the years, and that's what's fun about looking holistically.

Artworks take on new meanings when presented side by side. How does Betty Tompkins reflecting on the Me Too movement and text-based intervention on art history textbooks speak to somebody like the Guerilla Girls who are using mass media communications? It was an opportunity to foster those conversations.

KH: How did you arrive at the cover images?

AND: It was hard because so many works that are socially engaged, so many of them are text-based. Firelei Báez was an immediate frontrunner just because of how striking that image is. It was shown in one of our earliest shows within the series, “Between History and The Body” (2015). The way her eyes piercingly gaze out from the work itself. For me it was about having a cover that drew people in to look at it more.

For the second cover, I really wanted something to exemplify activism as a way to both relate to the title and the themes that we are exploring both within the book and in our exhibitions. Although this Andrea Bowers image of Johanna Wallace who is a trans-activist is not in the collection, it is so powerful because even if you don't know, it's a reference to Stonewall; there's something about someone throwing a brick that suggests a rupture.

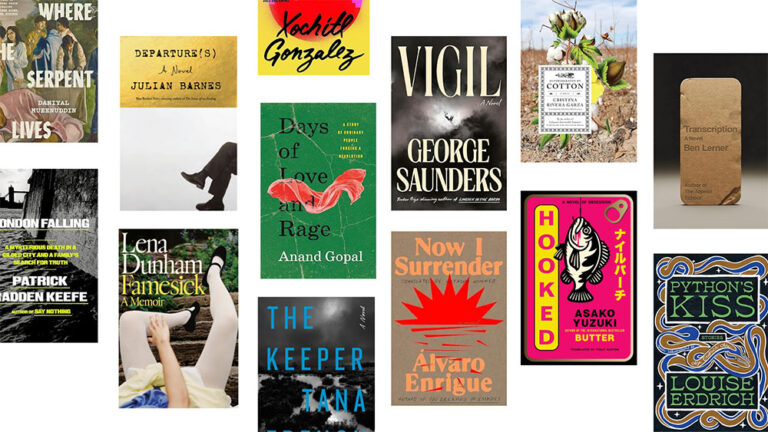

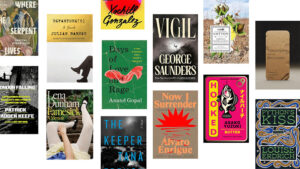

KH: What books did you look to for inspiration?

AND: One book that definitely inspired me was Young, Gifted and Black that was edited by Antwaun Sargent about the Lumpkin collection. There are points we're speaking from a collector's point of view or we're speaking from a more institutional point of view, and then there are points we're letting people speak for themselves. I was trying to find books that combine all of that, particularly in a way that wasn't necessarily tied to an exhibition.

Another book that was extremely helpful was the Noah Davis publication that David Zwirner put out. I'm attracted to very clean outlines. I'd like to thank my local Whitney bookstore for letting me come in and browse copyright pages.

KH: Were you worried that if you put two books in a slipcase people would be hesitant to read them?

AND: Sometimes books that are within a slipcase seem totally archival, whereas this is a play on the archive, but they're meant to be taken out and operate both separately and together.

KH: How did you assemble that group of curators and writers and authors you wanted to engage for the texts?

AND: There was always an ongoing list from working on exhibitions and grant making activities of the foundation. In my opinion, one of the most poignant portions is the accessibility round table which got together a group of people to discuss ways that this cultural sector could really improve and expand upon its accessibility practices in a way that's not tokenizing. A lot of people shy away from disability justice because no one wants to look like they're in the wrong. I respect both the honesty and the clarity that all participants of that roundtable put forward in thinking through new ways and modes of operating within cultural spaces in a way that's equal and doesn't other people. It's not necessarily about the visual arts, but it's also about how cultural institutions can make changes for the better.

KH: Now that you made one, do you feel compelled to jump into the next? Were there lessons you’d take to the next?

AND: I think the second one would come in the next five or six years and to see where we go from there. This was as a celebration of the Foundation's activities and that mission led me to dive deeper into the Shelley and Donald Rubin private collection, which I've worked with for a long time and helped form over the past 10 years. There are a lot of different branches to the collection, and it was really fun to pull back in the threads from the contemporary Cuban collection or the contemporary Himalayan collection and look at how all of these works can speak to each other and don't necessarily need to be siloed geographically or by time period. It helped me as a curator look at works that I've known for a very long time through new eyes, and gain a new appreciation of the collection and how it really speaks to the history of activism.

The primacy of so many of the artworks in the collection is the message. That wasn't necessarily an explicit direction that the collection took but really grew out of what the Rubins were attracted to. It's amazing to come full circle and see how over a 40-year collecting period, that all of these works, down to work we've acquired within the last year, speak to each other.

in your life?

in your life?