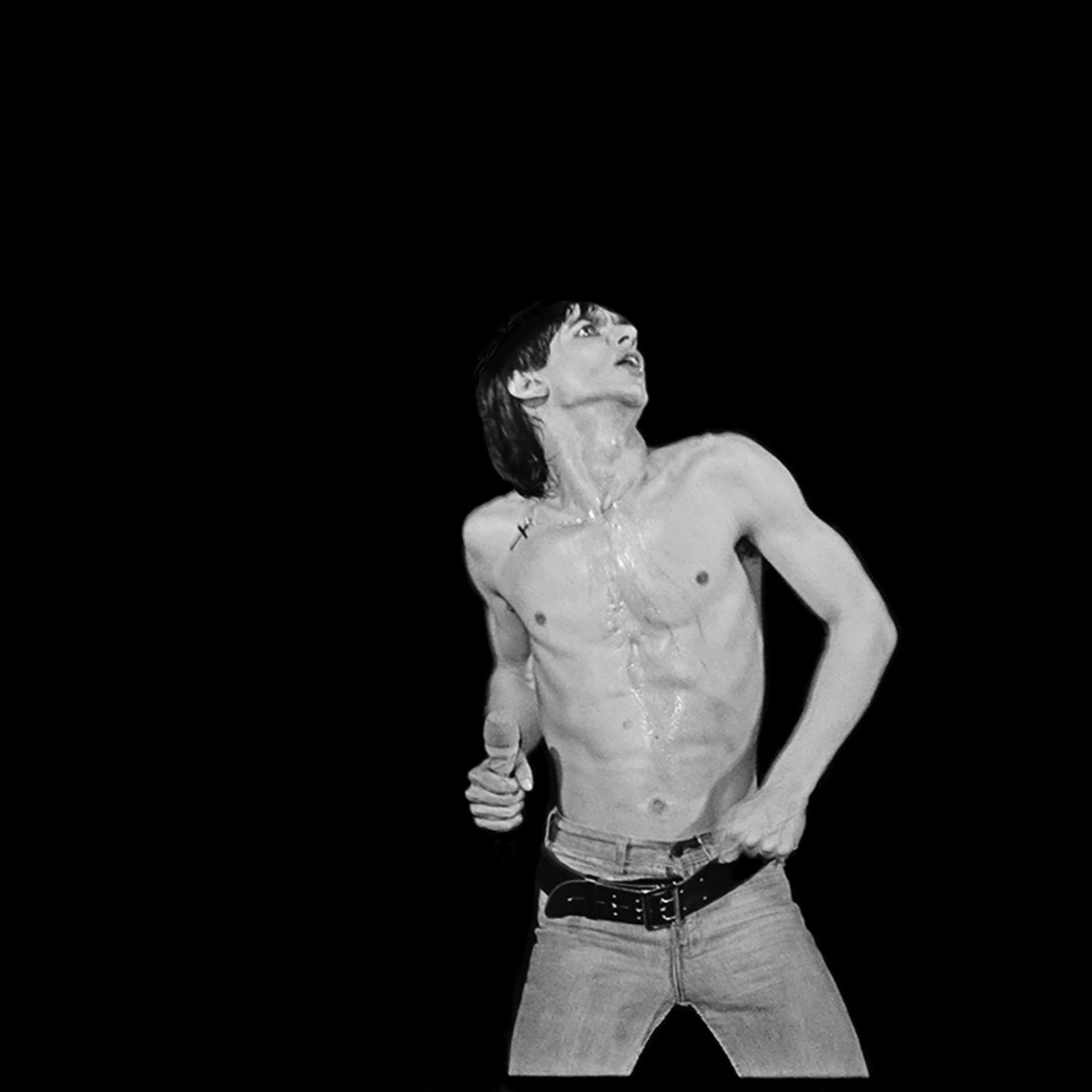

The first work of Tony Oursler’s I ever encountered was a head crammed under a mattress muttering “Fuck you, fuck you.” I was six years old, and I was shocked. The face was a film, projected on the fabric of the stuffed head. Its eyes seemed to search the room; was it looking for a singular target for this obscene mantra? Was there one among us who might be exempt? I wanted to be spotted by those flickering eyes but I suspected, in horror, that the Fuck You Head could not see me. Maybe I suspected that its performance was prerecorded or maybe I just picked up on the blinding solipsism of its misanthropy. Being six, the thought that I might never be fully seen or understood had only recently crossed my mind. This was both devastating and deeply inspiring. A nerve was struck. Why did I yearn to be singled out by the cursing, disembodied head under the mattress?

It was 1994 and I was not aware that I had picked a particularly edgy or cool artist as my new favorite. I liked Monet, I liked Warhol, I liked Calder’s circus and now I liked Tony Oursler. As eye-rollingly precocious a Manhattan child as I was, I did not, at that time, have a particular passion for contemporary art. I loved going to museums but I went to museums looking mostly for animals and magic. Really, I was obsessed with magic. The invisible world of colorless iridescence, where faeries and ancient gods flitted from one blind spot to another, was the plane on which I spent most of my time, practicing telepathy, telekinesis Matilda-style and playing out intricate psychodramas with my invisible friends.

I was also not aware that my childhood hero, Tony Oursler, not only loved magic, but was in fact a sort of magic expert and magic scion. His 2016 film Imponderable revolves around the story of his grandfather Fulton Oursler (also known as Tony Oursler in his day, making our Tony, in theory, Tony Oursler III), an amateur magician turned magic debunker. As long as there have been magicians, there have been those who made their name by publicly exposing others’ methods. Often these debunkers are magicians themselves; some are rivals or illusionists of a different variety. For instance, entertainers like Fulton Oursler’s friend Harry Houdini made a stunt of publicly disproving the powers of spirit mediums and exposing them as frauds. The tradition of the debunker-magician continues today in the work of mentalist Derren Brown, who unmasks the devices of faith healers and self-proclaimed psychics.

For those of you who have not seen Derren Brown in action (or didn’t read the excellent New Yorker piece that got me and my very discerning and cynical friends addicted to him), let it be known that he is a master magician. His brand of mentalism consists of guaranteed-to-blow-your-mind mind reading, couched in pseudo-scientific (like neuro-linguistic programming) and actually scientific (like the power of suggestion) explanations for how the illusion has been achieved through psychological manipulation and simple sleight of hand. It’s layer upon layer of misdirection and it works—at least on me—every time. The cognitive dissonance of simultaneous awestruck belief and neurotic analysis of the technique produces in me a flash of The Sublime.

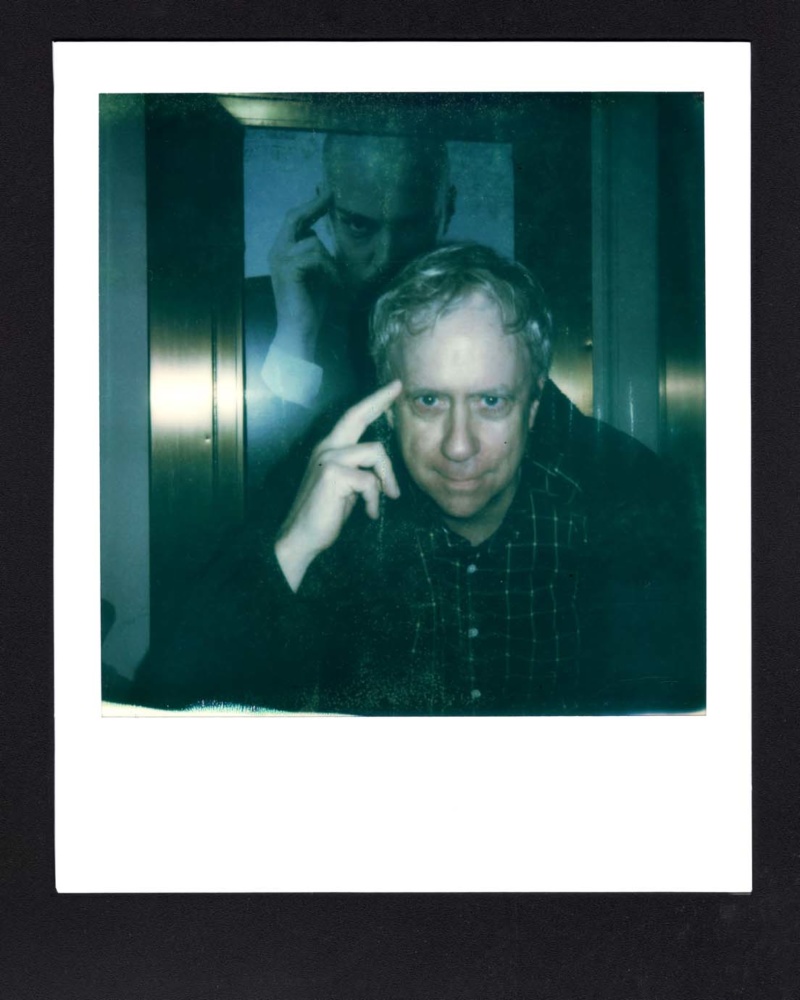

As I descended into the YouTube vortex of Derren Brown, I found myself wondering what someone like Tony Oursler would think of him. Realizing there is no one quite like Tony Oursler, I wondered what Tony Oursler in particular would think of Derren Brown. I imagined meeting Tony (who I had only casually stalked at the PS1 Book Fair) and taking him to see Derren Brown’s Broadway show, The Secret. When Cultured asked if I had any ideas for the film issue, I impulsively pitched my fantasy. Cut to me walking through Times Square on my way to meet Tony, searching for psychics. We’re going to document our adventure through Polaroids and I’m trying to find a backdrop for a portrait. When I get to the theater, I show him some pictures of neon signs I’ve found. He scrolls through his phone to show me the pictures he’s just taken of Times Square psychic shops. Was he location scouting too? “No,” he says, “this is just what I do.”

Tony is not only a creator; he is also an archivist. His archive, which exists as part of the Imponderable show and separately as a book of the same name, is a collection of what Mark Fisher might call “the weird and the eerie.” Weird and eerie are not the same as “creepy,” a word Tony feels is often inaccurately used to describe his work. The archive contains UFO photographs, occult paraphernalia, pareidolic flower petals, ectoplasm photograms, snapshots of Big Foot, hypnosis posters, Kirlian photographs by David Bowie, reliquaries, aura portraits, meteorite samples and original prints of the Cottingley Fairies. After the show, we visit Tony’s studio and he brings out the newest additions to his vast collections of oddities: double exposures of stern-faced mourners from the 1910s composited with ghostly handwriting: “spirit writing,” he explains. Tony toys with the idea of attraction to magic as an act of resistance. “People don’t want to be left in a lurch of rationalism, where you live in a brutalist world of capitalism,” he says. “The attraction to magic is analogous to a real experience, and what is the real experience?”

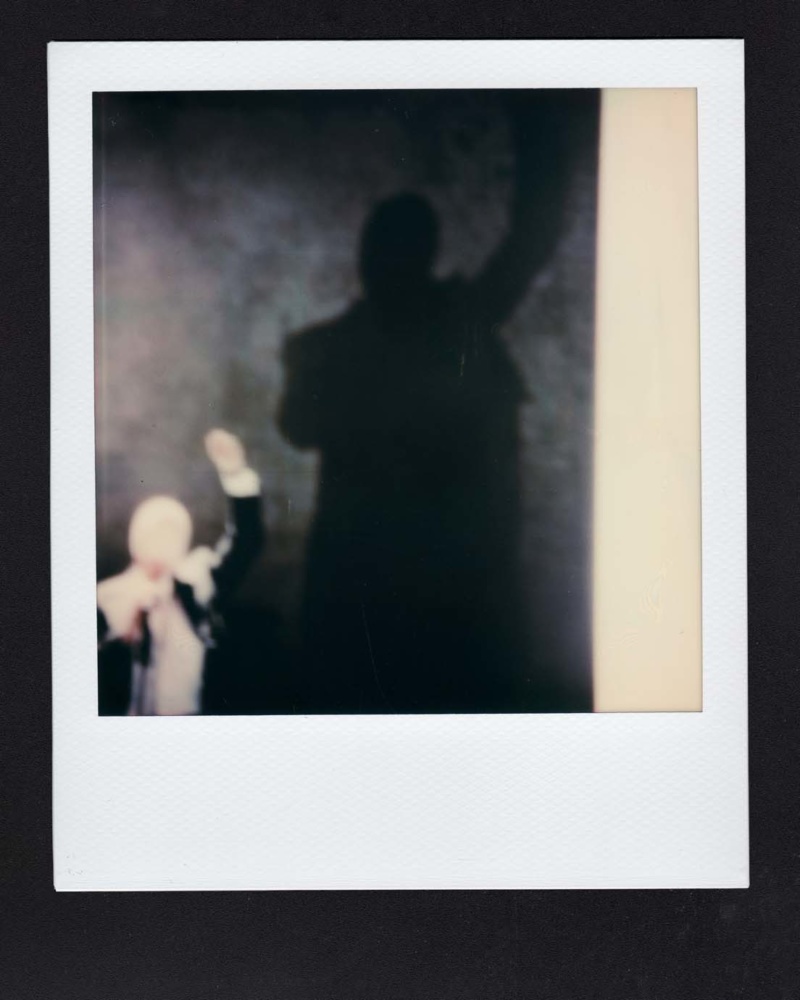

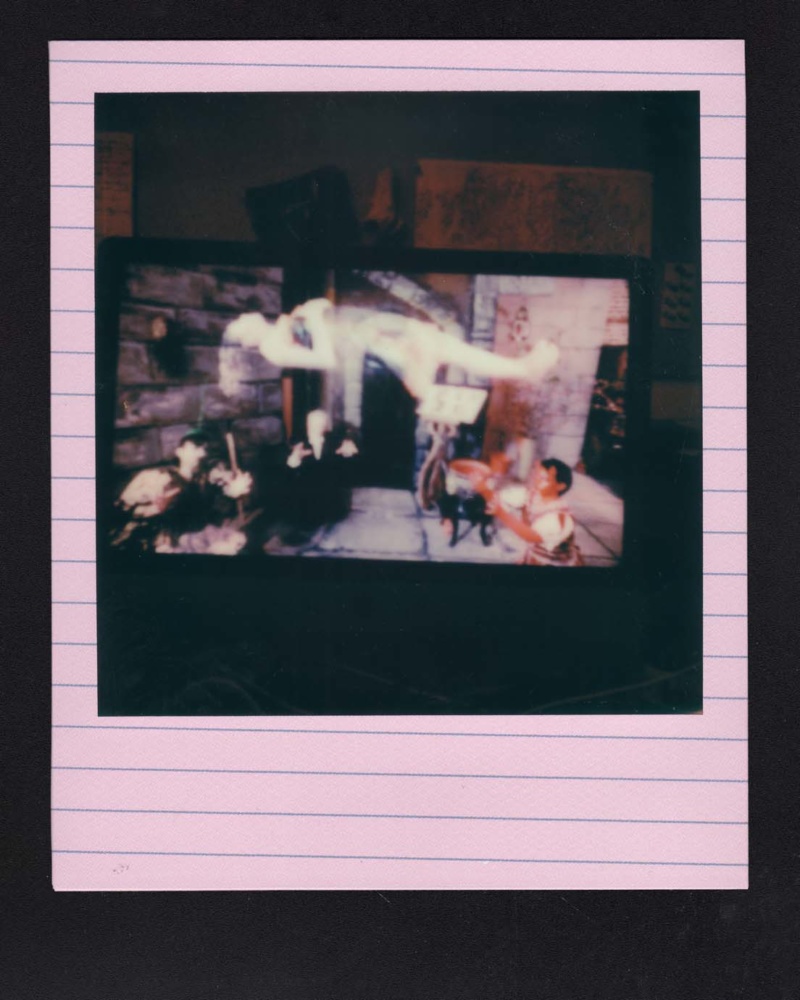

Watching The Secret next to Tony was most definitely a “real experience” for me. At the beginning of the show, the exquisite Derren Brown (who, in the flesh, is markedly more elfin and unreal than the everyman he convincingly passes as on YouTube) swears us to a vow of secrecy. Bound as I am, I cannot elaborate on specific details about the show but many of the scenes, Tony later explains to me, were “classic.” Being somewhat of a stage magic aficionado, Tony is less impressed by the efficacy of the trickery than by the aesthetics of certain setups; at one point, Derren is dwarfed by his own giant shadow and at another he blinds himself by wrapping his head in bandages. Tony is delighted by these knowing references to a golden age of magic—“totally 1930s”—but he doesn’t seem to see anything particularly novel in Derren’s uniquely psychological approach. Perhaps he sees the scientific twist as just another trick of misdirection: something pseudo-intellectual and shiny to distract from the simplicity of these ancient illusions. I, on the other hand, am completely destabilized. I am spellbound by Derren’s showmanship. Every mistake he makes seems deliberate, which somehow heightens his believability. The more I doubt, the more I analyze, the more I am carried away.

Derren’s magic relies heavily on audience participation. He himself admits that he employs some kind of secret rubric for assessing audience members’ psychological suggestibility and knowingly targets people who will most easily be hypnotized or fooled. Being at the extreme gullibility end of the suggestibility spectrum, I watch his (definitely sometimes random) selection of participants with an almost unbearable mixture of utter terror and desperate yearning. I want so badly to be called up on stage while the ugly fear that it could actually happen makes me sick to my stomach. This, I suppose, is something of the jouissance that must drive people to create and attend immersive theater. Perhaps I can find some forgiveness in my heart for the friends I’ve judged too harshly for loving Sleep No More. I think again of the seeking eyes of Tony’s sculptures and my longing to be/fear of being looked at. I ask Tony if he’s ever used artificial intelligence or motion sensors in his work because I always feel like I am being watched by his creations. “That’s kind of why I don’t have to,” he replies.

The other truly eerie aspect of Derren’s performance, I later realize, is the possibility that he can predict our thoughts and actions precisely because we are so predictable. It’s as if he has, through the trappings of stagecraft, fixed the number of possible reactions and thoughts as a limited set, and is simply selecting from a short list of multiple choices. If his foresights and telepathy are not “magical” then our behavior must be as mechanical as that of an automaton. “I’ve always had these theories,” Tony says, “that people are somehow strangely limited in the sense that if you charted somebody’s interactions through a day—the amount of words they use, the level of communication with which they interact with other people—they’re probably so much simpler than how they imagine themselves.”

The debunking of magic has always had to do with establishing which kind of magic should be believed. Efforts to establish stage magic over spiritualism, Christianity over witchcraft, witchcraft over capitalism or psychology over mind reading are, in a way, acts of deconstruction. “We live in a culture where, in the arts, a lot has been deconstructed; but if it’s just a cultural critique and it’s not offering a new paradigm, that’s a problem,” Tony says. As I walk home, seeing faces in the trees, making paranoid, nonlinear connections between Tony and Derren, I am overcome by a sense of unreality. Some of the Polaroids from the evening are still developing and part of me wonders if either of the two magicians will even show up on film. I find myself imagining that my attraction to Tony’s piece in 1994 was somehow a flash of foresight, a presentiment of this encounter. I wonder if the whole audience of The Secret was made up of plants, if the whole show was staged just for me. For a moment, anything seems possible. I take the pictures out of my bag to check, but the fact that they both show up in the photos might only prove that they’re spirits.