The 1970s and ’80s were a time of transition in America like no other, creating a trajectory that enabled even creatives of today to build from a place of inherent authenticity. This period represented a sense of freeness, abandoning traditional approaches to artistic process. The careers of some of the most prolific creatives in history catapulted during that time, from Halston to Nam June Paik and, of course, the renowned photographer Christopher Makos. This September, Daniel Cooney Fine Art presents the exuberant “DIRTY”— an exhibition showcasing a range of Makos’s unseen photographic work from the course of his resilient, multi-decade career. Setting the tone for our phone conversation this summer, Makos explains, “So much of these photographs is a moment in time; an experience, a memory... each is almost like a personal diary.”

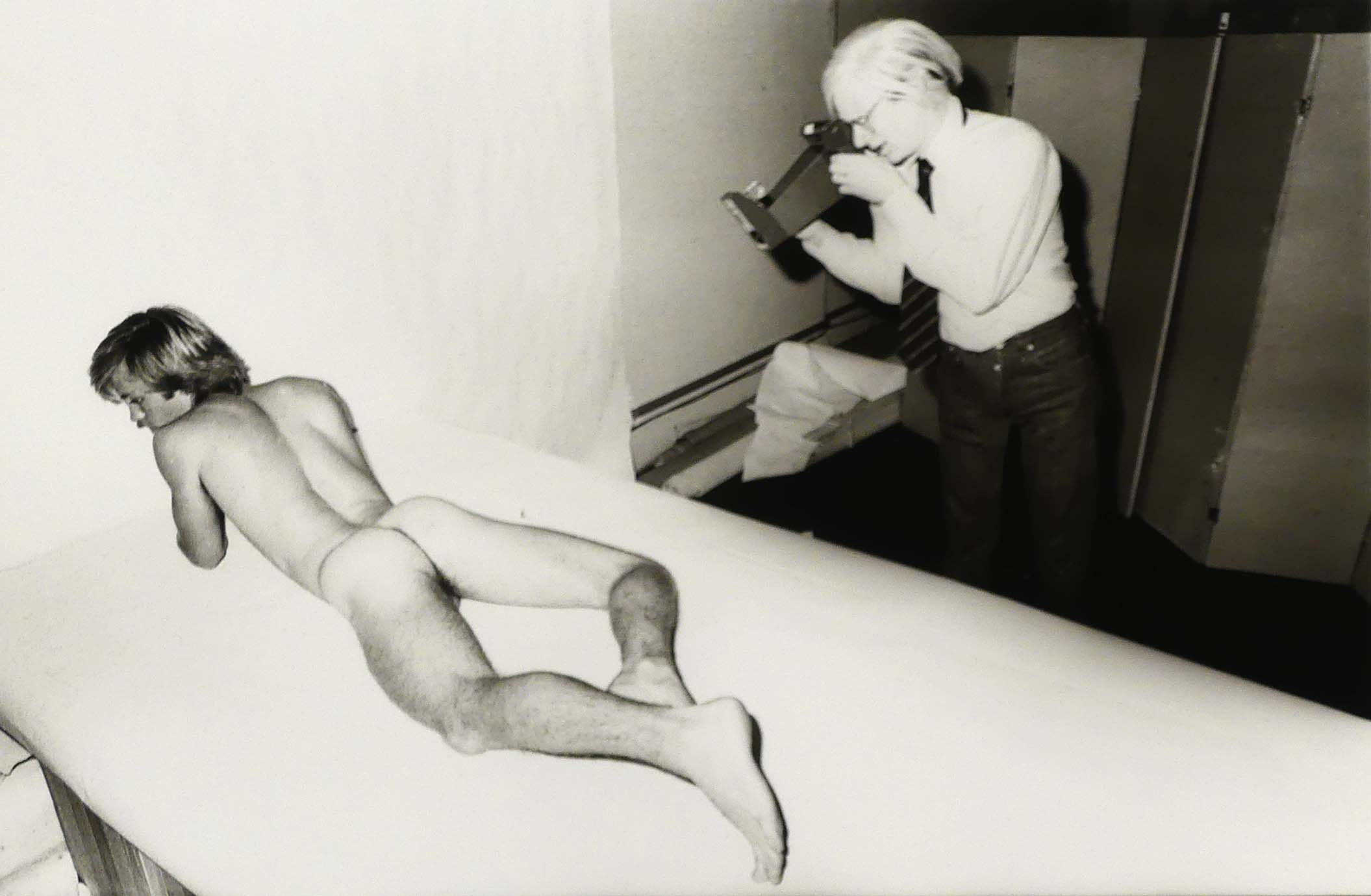

Makos is known for his dynamic friendship with Andy Warhol; almost a walking documentarian, he created countless snapshots of that liberated period. This latest show starts with photographs of notable personalities: Liza Minnelli kissing Warhol, Warhol kissing John Lennon and a striking series of Debbie Harry portraits.

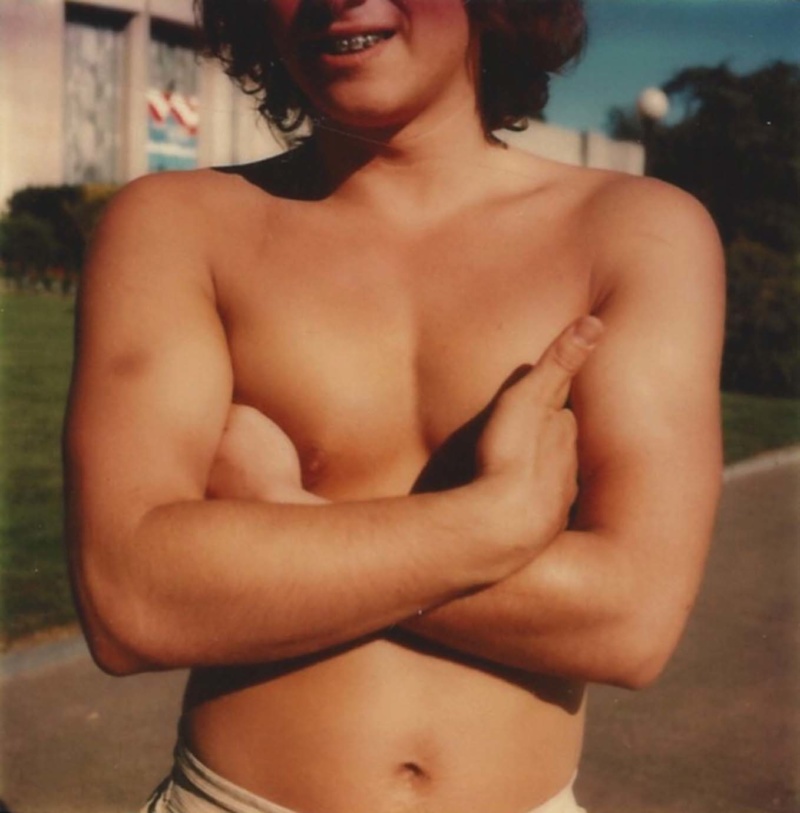

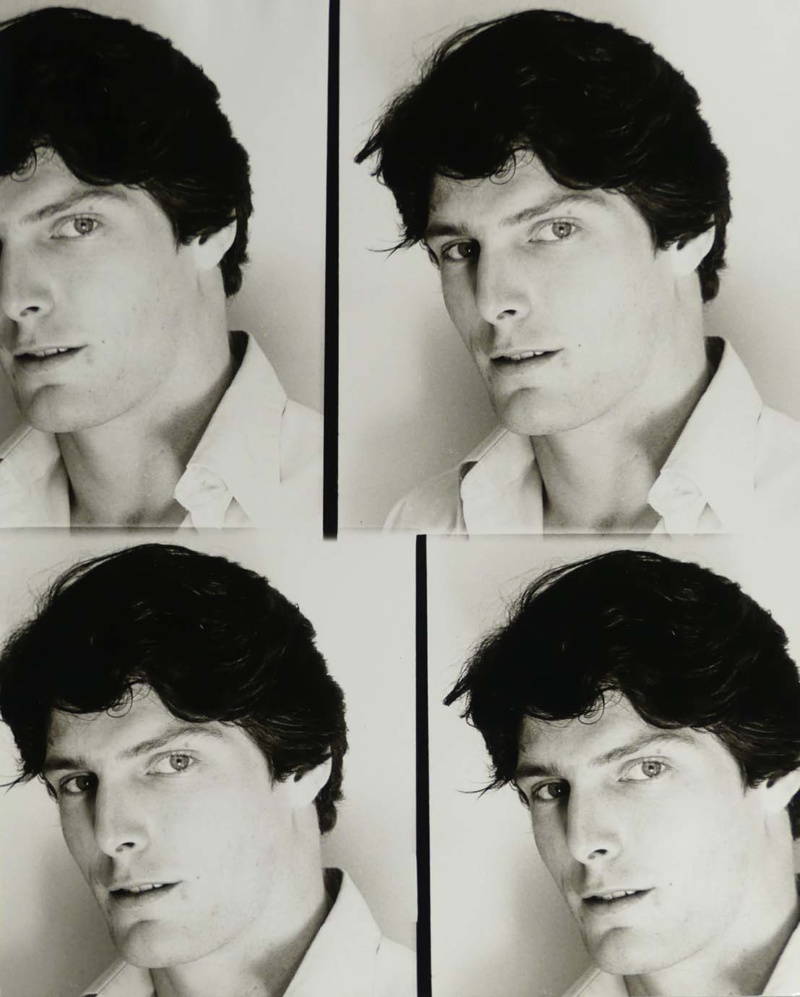

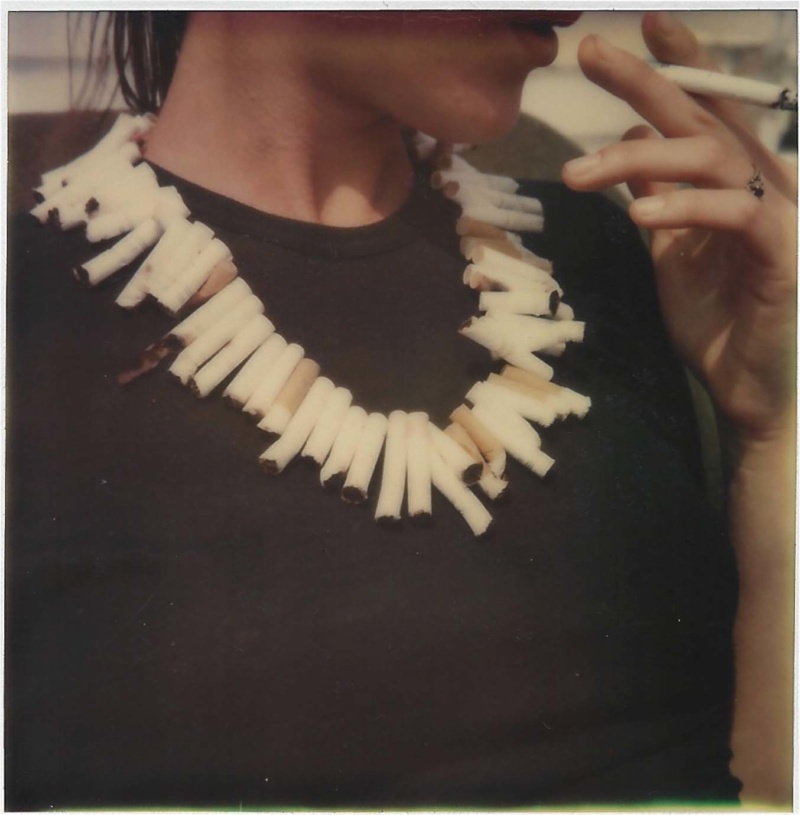

Conversely, despite the presence of celebrity, what these works reveal is Makos’s artistic agenda to capture the essence of vulnerability. Makos is an equalizer in terms of his subjects, famous or not, and is known to “look at everyone the same.” He took pleasure in depicting everyday life outside of the bubble of celebrity, and the quotidian ways people emanate vulnerability. Describing the young subject with his arms folded, signaling a bit of unease, in the 1978 Polaroid Boy With Braces, Makos says, “I photographed that kid because he had braces, and anyone who would look like that, you wouldn’t normally photograph.” Even in his portraits of notable figures, like the unique silver gelatin print of Christopher Reeve, Makos stripped down the actor’s heralding façade, offering an emotional and accessible dialogue with the viewer through Reeve’s eyes. It is, as Makos alluded, a moment in time—but with a narrative waiting to be unpacked.

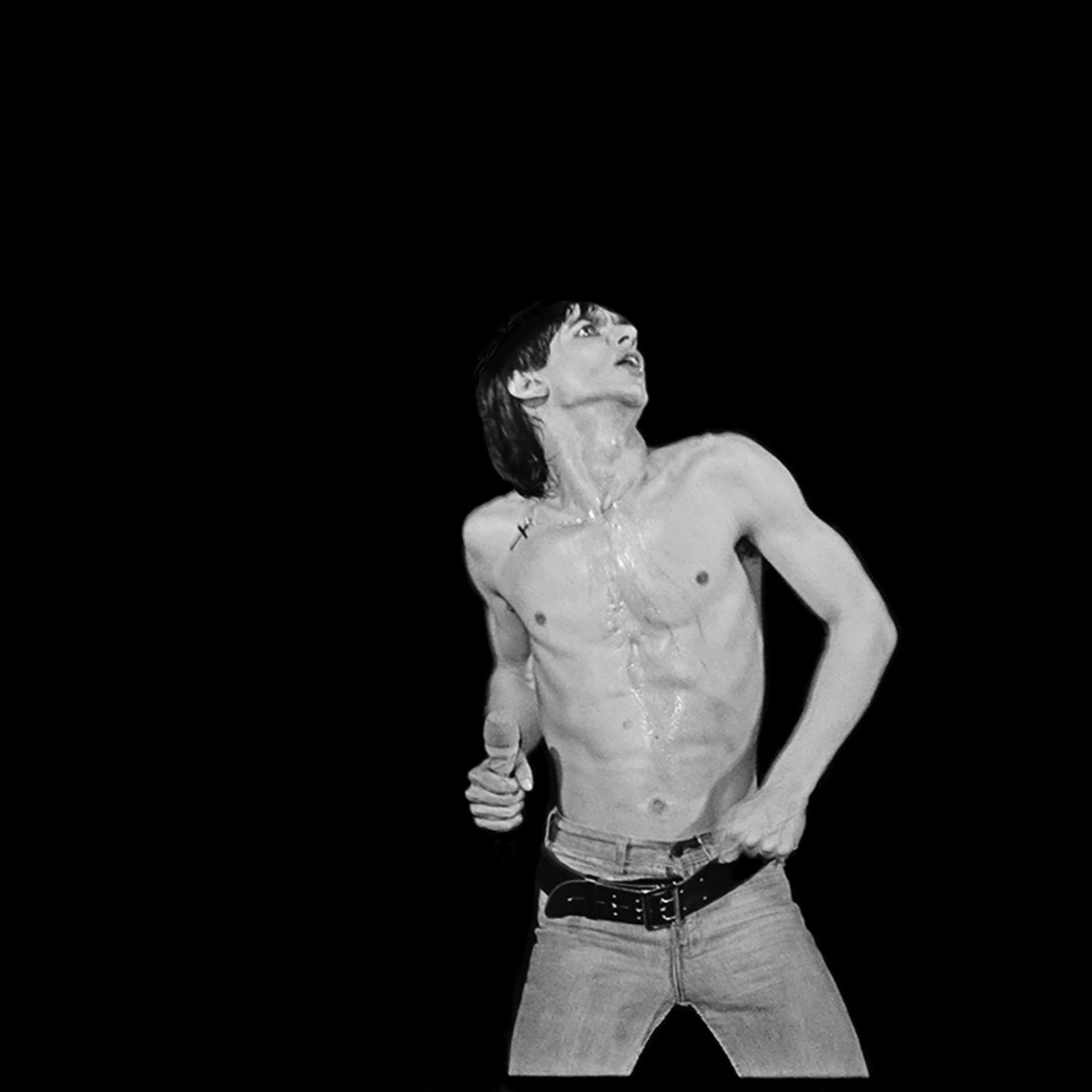

Throughout the show, this theme continues to blossom through the exposure of the nude body. Snapshots of male models in various poses and states of undress, from crouching to sitting wide-legged, like the 1981 photograph of Michael Kenny, display this range of comfortability from the subjects. Some models elicit a high level of confidence, while some of the works convey timidity. Sexual innuendos aside, the scenes evoke the personal questions we all face in terms of how we present ourselves and our insecurities. Especially in our current age of social media— as heaps of images of “perfect” bodies are thrust into our daily lives—many of us, me included, sometimes fall into rabbit holes of self-consciousness. Through these images, Makos highlights that embracing oneself paves the path to inner liberation.

“I love working with artists and finding things that will surprise people,” Cooney says of working on the show. “Christopher’s work may seem flashy on the outside, but when you get to look at it, you begin to realize it’s very sensitive. I feel there is a bigger story to Christopher as a person and an artist. I want people to realize that he was not just taking pictures; he was a part of something.”

In this present moment of cultural revolution, I thought it remiss not to ask if Makos saw any messages in his work that correlate with what is happening today, as protests for social, economic and political equality ensue. “I appreciate all the colors, and I appreciate all the diversity. It pisses me off when I see a little Black kid running away from police and they shoot him three times in the back,” he replies. “My work speaks to a much a freer time when there was less tribalism, and people could be nutty.” Moreover, “DIRTY” represents a perspective of sexual, racial and gender freedom that we have regressed from in recent decades. We have an immense amount of work ahead of us if we intend to build a fruitful future for all of society. Still, Makos’s photographs offer a chance to look introspectively, forcing us to embrace the vulnerability that will be necessary to imagine a liberated future.