In 2018 Boy Harsher, Kristina Esfandiari, and SRSQ released new records from Massachusetts, California, and Texas, respectively. And though these three bands stake out the outward limits of American geography, they more often than not share the same bills. This collective history and their complementary aesthetics have made them great friends—and a force to be reckoned with. The blunt end of this powerful coalition extends from the root. All three bands are helmed by powerful female vocalists and songwriters who address sharply relevant subjects of loss, intimacy, identity, Eros, and transcendence while engaging in a productive use of negativity—a defiant transgression against the now universal compulsion towards sameness and positivity.

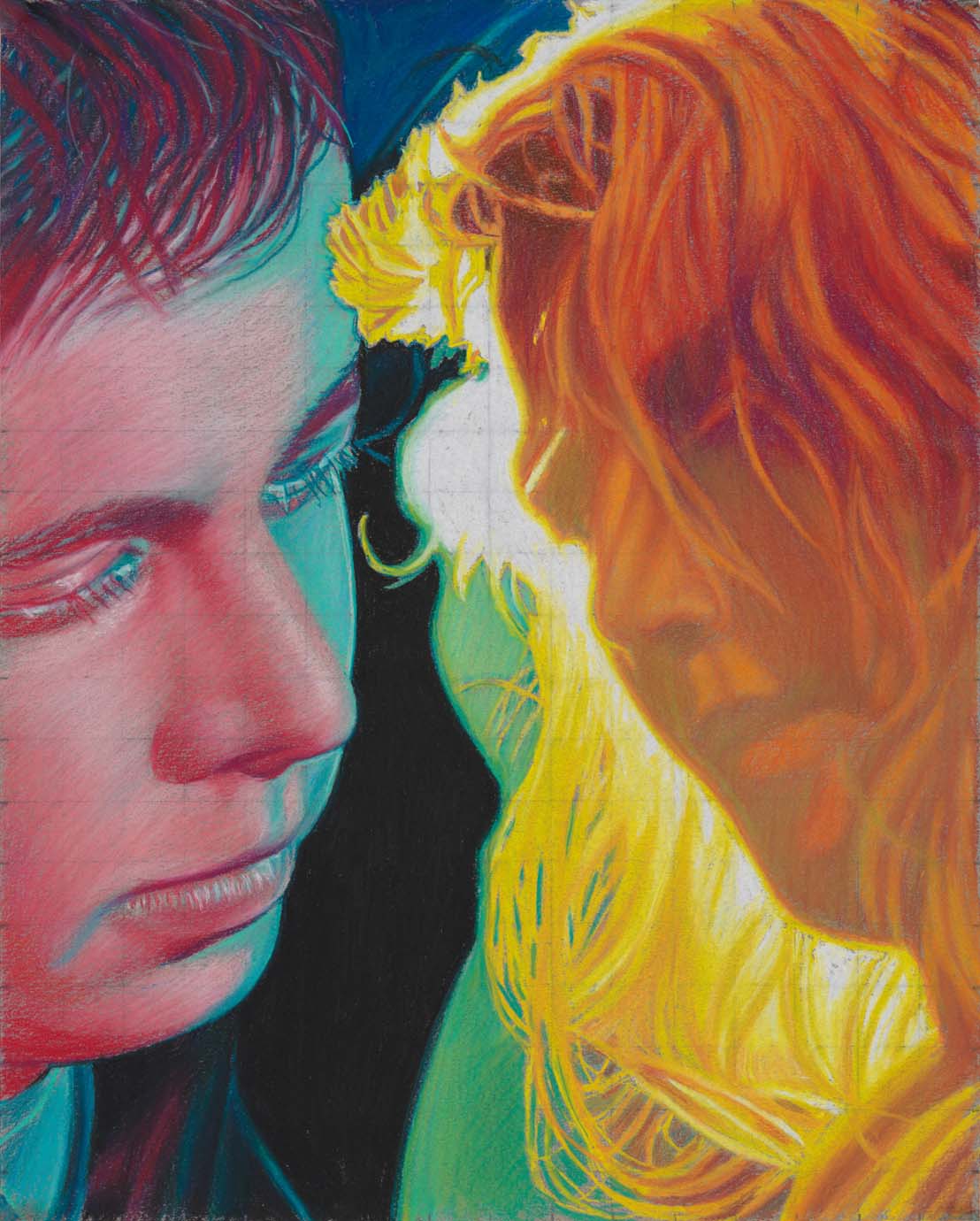

Boy Harsher Jae Matthews and Augustus Muller began as Teen Dreamz after the two musicians met in 2013 while living in the heat that is Savannah, Georgia. But it wasn’t until “Pain,” a single from their 2014 EP Lesser Man, that the band broke out with Soft Science Records, capturing an audience wide enough to keep the fantasy afloat. “Pain”’s dark minimal electronic dance beats and menacing lyrics spread around the world all the way to Berghain, the notoriously ruthless Berlin nightclub, where Matthews and Muller were famously denied entry while their song could be heard from within. A year later they would not only be let in but sell out the space in its entirety.

After Lesser Man, a steady rollout of material coalesced towards the release of 2018’s Careful. The album title speaks to their past but also their present. “The title comes from our own struggling to understand the word, especially when years ago we were working together in this chaotic relationship,” Matthews explains. “When we broke up, there was no more band and no more music. There was no Boy Harsher.” In the spirit of this moment, Matthews tattooed “Careful” on her back. “We weren’t speaking to each other then, so we really didn’t even have a plan for our set,” she continues. “We didn’t know what to do and went our own separate ways. So it became, ‘I’m careful,’ as in careful with my heart.” Eventually, scars healed enough for the two to overcome differences and pour it back into their music.

According to Muller, the development of Boy Harsher’s minimal electronic sound came from a necessary distillation. “In college we had no money,” Muller smiles. “I had just sold most of my stuff just to buy this cheap synthesizer, so it was just not a philosophical or existential choice. Now when we talk about getting more instruments, I often feel like we have enough to explore already. You definitely get lost when you have too many options.”

The same doesn’t apply to their inspiration, which runs wild, with anchors in both art and music. Conceptually the performances of Joan Jonas and Vito Acconci have been important to the equation as well as more contemporary peers like FlucT’s Monica Mirabile and Sigrid Lauren. “I remember watching Vertical Roll, the Joan Jonas piece, where she’s slamming a sledgehammer and thinking this is far more interesting than analog visual art,” Mueller says. “I think what we miss out on with performance now is that absolute devotion to the craft. What I truly appreciate withMonica and Sigrid is that they embrace their fear and act with no inhibition.”

Muller and Matthews were so taken with FlucT they invited them to perform during two shows: a dive bar followed by an airplane hangar. “I was curious whether they were going to feel strange, but there was no change in their plan or what they needed to do,” Matthews recounts. “They had a very strong disposition that didn’t flinch as the scale and crowds shifted.” Comradery and collaborative energy are an important part of the Boy Harsher recipe. “The sense of community is one thing that really makes this process work for me,” Matthew confesses. “If it was lonely or filled with too much drama or fighting, I don’t think I’d want to do it. But because it’s so familial it replaces a lot of things that I personally don’t have in my life.”

SRSQ Not since Elizabeth Fraser first toured America with her band Cocteau Twins in the early 1980s has there been a voice so emotive, nuanced and soaring as Kennedy Ashlyn’s of SRSQ (pronounced “seer skew”). Previously the vocalist and keyboardist of the duo Them Are Us Too with Cash Askew (who tragically died in the Oakland Ghost Ship fire), Ashlyn released Unreality in 2018 as SRSQ. The deeply personal album found its narrative in the memory of Cash and Ghost Ship and evokes a surreal world where each song creates a “non-space”—or perhaps more accurately, a place for unreality to live. Intertwined with staggering loss, this constructive confusion charts a path to move through trauma by creating a transcendent, if melancholic, environment with her voice and carefully sequenced synthesizers.

Ashlyn’s work on SRSQ began concurrently with Them Are Us Too. “The reason I make music isn’t just to sing. It’s the whole package. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed as having to work with songwriters. I’ve always been a songwriter. With Them Are Us Too I would bring a song to Cash and then Cash would come in with the guitar and contribute on the musical arrangements. Towards the end, it became more collaborative. After Cash died, I had this huge anxiety that people would not have faith that I would be able to carry the music by myself, so I was very specific about not letting any collaborators in for a long time.”

Uncannily, a collaboration did occur in her subconscious around the song “Mixed Tides.” Ashlyn explains: “I woke up from a really intense dream about Cash and I feel like it was the last dream when she really visited me. I had dreams about her, but this really felt different. I just woke up in tears because it was the first time I was happy since Ghost Ship.” This was in June 2017. The artist ran to the studio, writing “Mixed Tides” in six hours.

Ashlyn’s vocals on Unreality clearly demonstrate her ability to articulate the power and subtlety of her expression as a trained and devoted singer. Growing up in Davis, California, she pursued lots of different versions of vocal training. She was in choir, studied jazz and opera as well as musical theater. “I feel like I have a lot of control over my instrument more than any other skill and can therefore approach things that are challenging for me in a thoughtful way. I still also practice a lot,” she says. “Vocal training gave me the confidence not to hesitate.” This quality is especially evident during her live performances. From the crowd’s perspective, she appears to be living the song rather than performing it. “The hardest thing is that I want to maintain the intensity and the authenticity of the heart of the song while I’m performing. I’ve found new ways to trigger those emotions so that it isn’t fully performative and I’m actually experiencing it in that moment,” Ashlyn says of her stage presence. “I’m not trying to trick myself as much these days.”

Unreality and the related video, “Permission” (2018), both grapple with tragedy and the characters associated with it. “I love all these women in history, like Edie Sedgwick and Marilyn Monroe, and that their tragic flaws are an archetype. With Marilyn Monroe, the world demands full access. As soon as there’s any depth or vacancy, it’s shut off. That’s what the song “Martyr” is all about. It’s not about the content of the song. It’s about the performing of the song. It’s like I’m slitting my wrists on the stage and at the end [of the night] there’s nothing to do but a shot at the bar … like what else am I supposed to do?”

As a result, there’s an interesting dichotomy that exists in the music itself. There’s an interior grief that’s expressed in such an effective way that people can identify with it and, for as much pain and sorrow as she packs in, there is also relief and freedom. “There is a cathartic effect,” Ashlyn says.

Part of the performance’s intensity comes from the pressures of identity. “I think so much about my gender performance,” she says. “My physical projection is like armor. I’ve heard high feminine people saying my makeup is my armor. One of the things Cash’s girlfriend and I did two days after Ghost Ship was go to Sephora to try on makeup, as though there was something about taking control over your representation that does this ‘fake-it-until-you-make-it’ thing. You’re showing you have your shit together and that you’re strong.” For Ashlyn, it became a way of re-taking possession of herself.

Ultimately for Ashlyn, Unreality was an event followed by a reaction but “god forbid I have to go through something like that again.” Thinking towards the future of SRSQ, Ashlyn talks about having songs trapped in her head. “I think there are themes that are a bit grander. Them Are Us Too’s Remain album was about love and coming of age, but also starting to deal with depression and mental illness. I’m still growing up in a lot of ways and moving away from existential crisis and towards a peace of mind and what it means to be alive.”

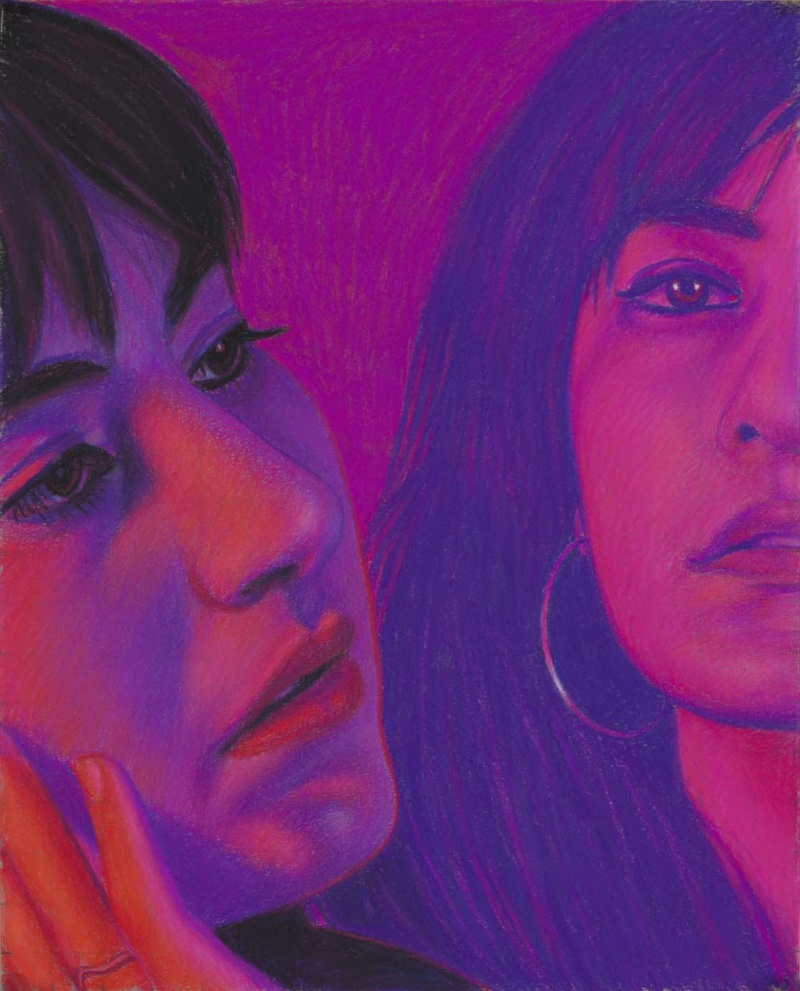

Kristina Esfandiari Fast-forward to the Brooklyn club Elsewhere, where Kristina Esfandiari was invited to appear before Boy Harsher for their Careful release. The club was packed from front to back for what was to be a true celebration of new dark electronic music. The entity that Esfandiari appeared as that evening was NGHTCRWLR, a rap and R&B-inspired dark industrial solo project, which she aggressively performed amidst the crowd while her vocals emerged from the rolling syncopation of ominous beats exploding on the dance floor. Earlier in 2018 she released the double EP Lover Boy/Dog Days under the band name Miserable along with the single, “I Wanna Be Adored” (a cover of the classic Stone Roses shoegaze anthem), recorded with her original band King Woman. “I can’t remember why I chose to do it,” Esfandiari says. “I ended up in Sacramento, which is my hometown, with my friend Pat Hills who records all my stuff. I was doing a show out there with my band and I was like, we should do this cover. And we just recorded it and didn’t think much about it. And then we put it online. It was the first cover I’ve done and people still message me every day about it.”

It’s precisely this combination of charismatic delivery, casual disregard for results, and a passion for originality in the studio that bonds Esfandiari to her friends as well as her fans. With “I Wanna Be Adored,” Esfandiari claims her inward vulnerability and transforms it into a commanding declaration of who she is and what she insists on. The takeover of the song in subject, content, and delivery is consistent with her belief in music as a primal release and a way to transcend the present. NGHTCRWLR, for example, is a project Esfandiari describes as “a force that presented itself to me, having to do with past life regression.” She continues, “It’s not a hybrid of styles but a form in itself.”

On the contrary, her performances within Miserable have a softer energy—what she describes as an “evolving angsty feeling that’s inside me that never got to express itself.” A single lyric like “candy-coated oppression” from the title track “Lover Boy” connects directly to the gaslighting she has experienced in relationships, alongside the depression that comes with the loss of identity and self-worth. Written on a trip back to New York, the song carries a message of strident refusal. “On the flight I just had chills up and down my body and I just kept hearing the words: ‘Lover Boy,’” Esfandiari says. “I wrote it down and underlined it. I had all four songs in my head and could hear the arrangements. It’s how it works for me, I usually hear the sound and write the album around the title.”

The visitation of music and lyrics directly into Esfandiari’s consciousness follows a pattern that began with the genesis of her doom-metal project, King Woman, and had further autobiographical connotations: “King Woman changed my life. People have different ideas of spirituality and for me King Woman is very spiritual. We were playing a place in Santa Cruz called the Witch House, which was a very small room. During the set, I had a personal experience where I blacked out and woke up on the floor screaming, having an out-of-body experience. As I came out of it, I was baptized. My energy just shifted. It was powerful, like an ancient force that propelled me forward.”

As in the case of Boy Harsher, Esfandiari’s musician and artist communities are important ingredients to her success. Nick Cave has always been a major force in her pantheon of artists and whose mere presence was “lifechanging.” But it was an early experience with Alanis Morissette’s 1995 Jagged Little Pill that really broke things open. “I used to listen to that record on a PlayStation because I wasn’t allowed to listen to it at home. I would stay at my older sister’s house and blast it. I didn’t understand the lyrics. I think it must have built up this kind of energy.”