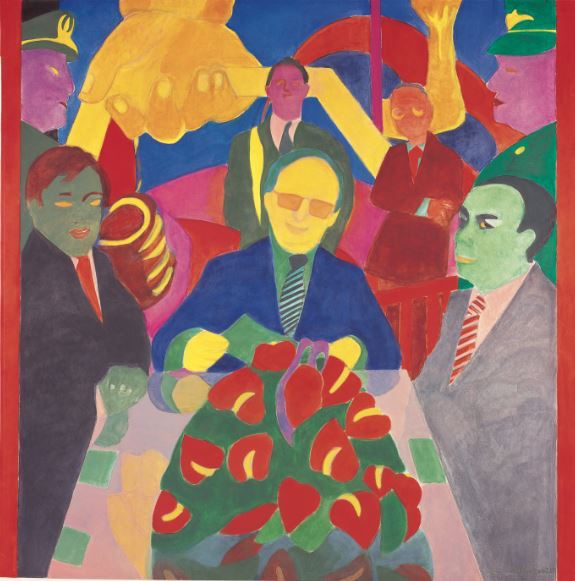

Opening at the Pérez Art Museum Miami this Friday, Beatriz González: A Retrospective is the first large-scale, U.S.-based retrospective of the Bogotá, Colombia-born artist. Born in 1938, González’s career spans six decades; her radical work (she’s described herself as a “transgressor”), drew from her own investigation of Colombia’s sociopolitical climate, the bizarre global emphasis on European artwork, meditations on the media. It has never been simply Pop Art, the movement with which she’s most frequently associated—González once called her flat-figured, brightly-colored works, which in their own way document histories at risk of erasure, “underdeveloped paintings for underdeveloped countries.” Curated by Tobias Ostrander, A Retrospective highlights the nuance of her work, its breadth and complexity and influence. Ahead of the show, we spoke briefly with González over email about her history, her future, and what she’s reading.

Were you also an artist when you were very young? Yes, and my drawings have always been admired. I knew very soon the word “artist.” In 5th grade of primary school, I drew a tangerine in charcoal. Our teacher showed the drawing to the class and said: “An artist... an artist.”

You’ve described yourself as a transgressor, too. I loved to transgress the “art laws”: color, composition, material. But also, my artworks referred to topics that upset many people. That’s why, during my early years, I couldn't sell any of my pieces.

You have quoted the saying, “Art tells us what history cannot say.” While that quote isn´t mine—I don´t know the author—it is too close to what I think. Art has a special language that allows it to approach history, without making an academic narrative.

In addition to making art, you have also taught many students. Did their points of view, at any point in time, inform your perspective of the world? How so? My approach through study groups and young artists has to do with critical readings of great thinkers of the twentieth and twenty-first century as Boris Groys, Didi-Huberman, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, among others. I do not seek to approximate the young students to my work, but to form criteria through reading. In this sense I also learn from the readings we share.

What are you working on now? I’d love to know what you are pondering, reading, examining. I’m always an active artist. I am working on a series about landscapes associated with natural tragedies in Colombia. In relation to my readings, I’m reading different texts; I have a study group with young artists and we read about philosophy and aesthetic—Boris Groys, Georges Didi-Huberman. During summer, I read Colombian recent literature, authors like Pablo Montoya and Tomás González. I also enjoy reading poetry.

What are some of your daily rituals before--and after--you paint and work? You do several different types of work so I am curious about how you create boundaries and care for yourself throughout. Painting in the morning, drawing and reading in the afternoon. I have not seen necessary to put barriers between my disciplines; they all relate. Sometimes the readings affect the paintings and other times the paintings lead to reflections on what the books express.

Beatriz González: A Retrospective is on view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami through September 1, 2019.