What does it mean to look alive?

That question is the undercurrent of “De Anima,” the Swiss Institute’s newly opened exhibition pairing sculptor Elizabeth King and Louise Bonnet. Orchestrated by director Stefanie Hessler, who introduced the artists at one of the institution’s openings just over a year ago, the show probes the bounds between the living and the lifelike, the theatrical and the intimate, the grotesque and the precise.

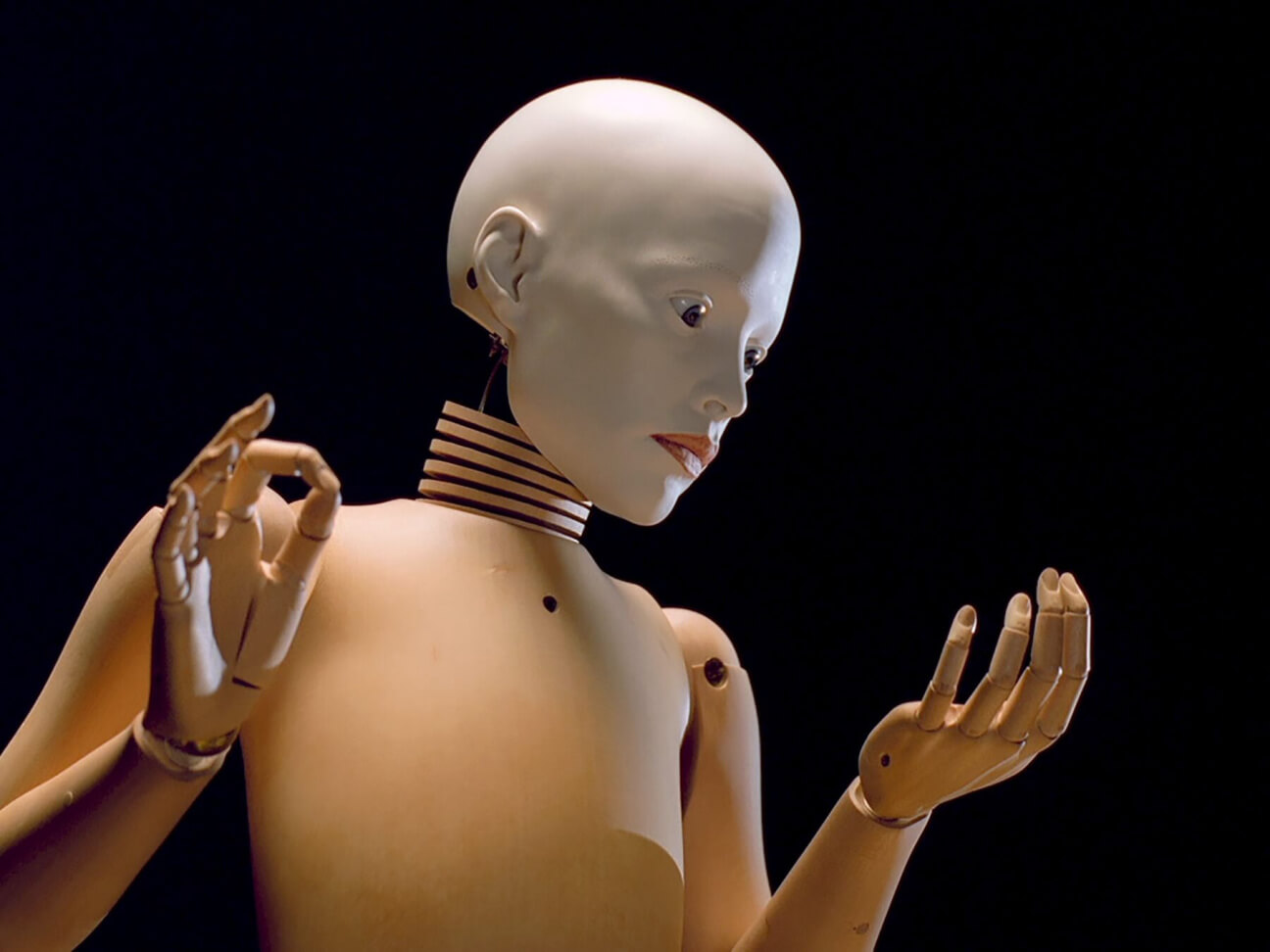

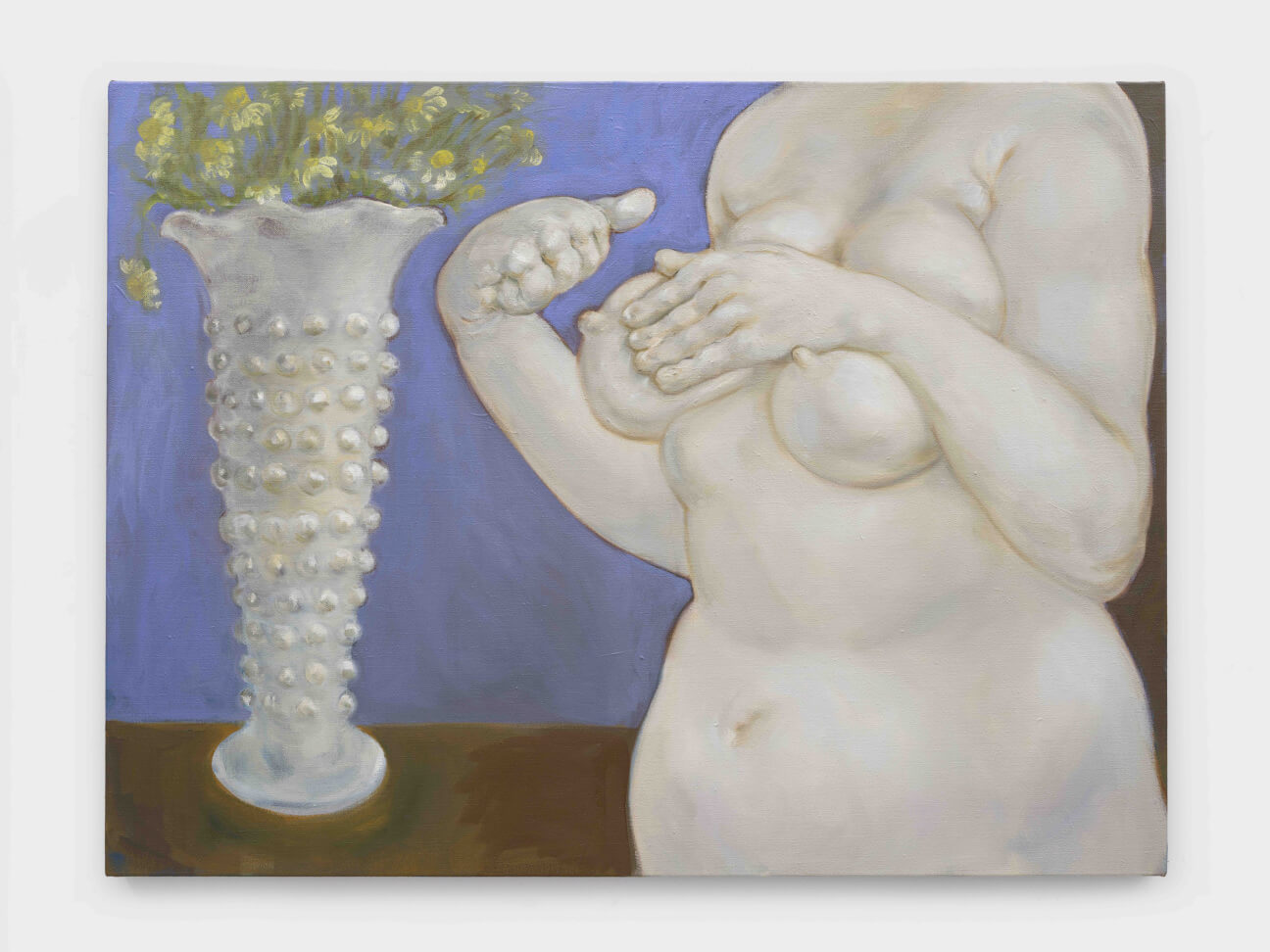

King, known for the hauntingly articulate automata that have fueled her practice for over five decades, and Bonnet, whose canvases are buoyed by fleshy avatars, found an unexpected kinship through gesture. Their output—spanning stop-motion films, puppetry-inspired sculptures, and massive oil paintings—acts as a persistent reminder of their mutual fascination with the small, often involuntary, movements that betray us: the twitching eye, the clenched jaw, the tripping foot.

In an exclusive conversation with CULTURED, the duo speak candidly about the invisible labor of artistry, their anatomical fixations, and why they make work for an audience of one.

CULTURED: How did you become aware of each other’s work, and how did the idea of the Swiss Institute show come about?

Louise Bonnet: It was Stefanie Hessler, the director of the Swiss Institute, who had the idea to get us together. It was very unexpected. That’s where she’s pretty genius, because the more it went, the more it made perfect sense. We met for the first time at a Swiss Institute opening last year…

Elizabeth King: And then we just basically talked the whole time. We spoke about clothes and the body and the process of making things and the art world and how we navigate it. There was just an instant, almost physical simpatico. I just wanted to talk to Louise. What she said kept surprising me, so it just made me want more…

Bonnet: We’re both interested in putting too much emphasis and attention on tiny little things that the body does—things that actually would not matter [to most people] or that you’re not aware of.

CULTURED: Since that moment, how has the conversation between you two evolved? How often were you talking during the making of the Swiss Institute show? How much did you know about the archival works you were including, Elizabeth, and the works you were making, Louise?

King: Since the show was set up, everything I’ve done in my studio this whole year has been in a kind of dialogue with Louise’s work and with Stefanie’s thinking. There have been some wonderful chances for me to look at my work from the outside that I’ve relished, but we’ve also had a number of conversations with the three of us together. [Louise and I are] both really involved with the image of the hand and the behavior of the hand, but an additional thing that connects us is our own hands—the skill that we have labored to master. Louise on canvas and me with the materials that I use. It’s often been a taboo subject in the mainstream art world—which is so geared towards content, the intellectual message, and one’s actions in relation to larger zeitgeists and the political cosmos that we live in— so locating what we do with our hands, what we do all day long, is something I really relate to Louise’s work with. Louise, I know that you’re painting as you go. The editing process within an image has to be profound.

Bonnet: It’s true. I realized, especially this time, that I almost have to make the whole thing [in order] to see if I don’t like it. And you’re right, the other day, I thought, Why is my neck weird? I forget that I do this thing all day long, this gesture of painting. I don’t realize what it actually does [to my own body].

King: You just don’t know until you’ve made it. The same is true with our show. All year, I thought, What will our work look like together? I was deliciously in the dark about it.

Bonnet: It’s been horrendous because everyone was asking me for photos when I was in the middle of not liking it. But I love what you said last time, where you [explained that you] make the inside of the heads [of your sculptures] perfectly, even though you know no one’s gonna see them in the show.

King: I think that we both work endoscopically. An endoscopy is a medical term for the inside of the body. We both work from the inside out. She’s building the body in that canvas from the inside out, and me too.

CULTURED: You’re both interested in the invisible or overlooked in your work—those microscopic physical gestures you were mentioning, Louise—but also in the invisible labor of being an artist. Where do you trace that interest back to?

Bonnet: You used to build forts when you were little to hide in, right Elizabeth? And I would spy. I loved spying. I think it’s basically a more acceptable version of doing it now. I just wanted to see and not be seen.

King: When I was a little older, I discovered a book by Gaston Bachelard called The Poetics of Space. The contents of that book are parts of the house—faucets, drawers, attics. I was staggered to find that someone had written this book, and had written a philosophy of those places. I would go to sleep at night imagining myself setting up shopping in those little [domestic] spaces; they were always hidden spaces … I should have been an architect, but my fascination with built spaces—and the accidental things that happen in built space, and my desire to occupy those zones or invent them in my mind—led later to my conceiving of the body as such a space.

CULTURED: Speaking of visibility, do you show your work to people around you before it’s done? Who do you talk about it with?

Bonnet: I had to learn that I had to be able to talk about my work, and that it was actually very useful, because I could then also articulate it better to myself. But it’s definitely not natural to me. I have a couple artist friends who I can ask, “Is this working or not working?” My husband [Adam Silverman] can actually be super amazing because he knows what I can do.

King: What about when the work is on show, Louise? Once you let the work out of the studio, does that change your will towards conversing about it?

Bonnet: That’s interesting because usually I don’t work with a theme or an idea. It sounds like I do, because by the end, I kind of make something up.

King: I’m so interested in hearing more. I’ve wondered [about your work] all year. This is unusual for me—a two-person show. You mentioned the word “meltdown” in one email, and I thought, Oh, it’s happening to Louise, too. You just don’t know how people work. It’s just a roller coaster of emotions, and you just can’t imagine at midnight that you’re going to actually get your confidence back the next morning.

Bonnet: This time I couldn’t think, Well, if the work sucks, it sucks. Or, It’s a gallery. They’ll find another way to do business.

King: Is that because it’s a two-person show?

Bonnet: It’s because I really cared about what you would think, and I wanted it to be good. That’s a recipe for disaster.

CULTURED: You emailed throughout the show prep process, did you exchange texts or references as well?

King: Stefanie talked about Throwing like a Girl, [an essay by Iris Marion Young]. The Swiss Institute asked me to suggest some books for their library, so I immediately got about 30 books down from my bookshelf that can’t possibly go to the library. Among those books would be The Third Policeman [by Flann O’Brien], another book by O’Brien about some impossible architectural spaces and impossible scales of tininess, Walter Murch on editing film, three orthopedic manuals that were published in the ‘60s for orthopedic students…

Bonnet: I was reading about spies. I got the [Special Operations Executive] manual, which was given to British spies that were dropped into France during WWII and prepared them to seem French. It’s all about “tells.” Like the way buttons are sewn—in France they’re parallel, but the British used a cross. The Nazis would know these things and arrest you if you had your buttons sewn wrong. Or if you put your hands in your pockets—the French would never put their hands in their pockets. I love that kind of stuff. It’s like acting, these gestures that you’re not aware of, but that would say something.

King: I found myself thinking that our [practices]—as different as they are—they both often deliver a body on a stage. The stage might not be a recognizable one, but there’s a stage. In your case, there are props. In my case, there are lights and a potential performer. In the Japanese theater of Bunraku, the same puppet can act in different roles in different plays. Between the plays, they hang in the storeroom waiting for their next role on stage. I feel that way about my sculptures, because they’ll be posed differently from one show to the next. For me, it’s a whole new sculpture. And I think that’s true in your paintings as well, Louise.

CULTURED: Elizabeth, you mentioned Throwing Like a Girl, which speaks of gendered norms around movement. How do you both think, or don’t think, about the role of gender in your practices? Did it come up in thinking about this show?

King: We have talked a little bit about this.

Bonnet: I’m sure you don’t go around your life thinking, I’m a woman, as you do stuff, right? I don’t think of my figures exactly as that. I feel like they’re really more inside of me … But I love thinking about how we adorn certain [body parts] and then others we hide away.

King: There’s a wonderful essay about the French writer [François] Rabelais, who wrote Gargantua. It’s a brilliant essay about Carnival and how on that day, everybody dresses the opposite of what they are, and it becomes okay to mock or expose or exaggerate protrusions—butts, boobs and, yes, genitals. There’s something Rabelaisian about what we’re talking about. I often think about how, in the history of artificial life, it’s almost always a man making a woman. It’s the same, right now. How many women do you know screaming about A.I.? It’s all these guys who are climbing all over themselves about artificial beings.

Bonnet: And they’re so afraid that they’re gonna overpower them, because they’re always made as inferiors or women. That’s why they’re so afraid that there’s gonna be an uprising of A.I.

King: One of the reasons I’m fascinated with the body and its quirks is that those are the things that can’t be simulated. Two things about that that have struck me in the last month. One, I was watching a program about contemporary robots. A guy at Columbia named Hod Lipson was saying it’s easier to simulate the mind than the body. We’re talking about general intelligence and problem solving, yet we still can’t make a robot whose hand can make it to his mouth without problems.

The other thing that struck me was said by Jaron Lanier, an expert about cybernetics and artificial life. He said, “We keep talking about A.I. as a creature one minute and a tool the next. Which is it?” I’m really interested in it as a tool, but I’m really suspicious of all of the technocrats that keep trying to deliver it to us as a creature that we’re to respond to with all the innate and helpless ways we respond to things we think are alive. In a way, I have that question about my sculptures. Are they instruments, or are they portraits? I’m not immune to this ambiguity.

Bonnet: I just read somewhere that there’s like billions of terabytes of energy being wasted by people saying “thank you” and “please” to A.I.

King: You want to ask yourself, what is it in us that entails those responses? I always was interested, even back when I had such little overview of myself in the world, in the one-on-one encounter. I always imagined one viewer at a time encountering the piece, and that it would be an intimate encounter, as opposed to a mass audience. That one-on-one exchange is where we speak to the other entity not as a he or a she or an it but as a you. We’re speaking directly to them. The philosophical nature of that is fascinating and complicated.

CULTURED: With the Swiss Institute show, if you could distill an emotion you’re trying to evoke in that audience of one, what would it be?

Bonnet: In my case, it’s like when you see someone scratching, you start scratching. Sometimes you can’t tell what they’re doing, but your body will remember doing that.

King: So much is always happening that is in addition to what you’re actually thinking. Think of all the times you’ve left the museum, and the piece that didn’t leap into your head the first time you saw is the piece you remember the most … I hesitate to say what I hope the viewer will take away from seeing the show and my work in it. In a way a more interesting question is, what will I think of the work when I see people looking at it? Because that’s the moment when you get hit with what you really did do. You’re always doing so much more, and also so much less, than you think you’re doing. Sometimes decades later, you have an epiphany about what you’re actually doing. This year has been a little bit like that for me.

in your life?

in your life?