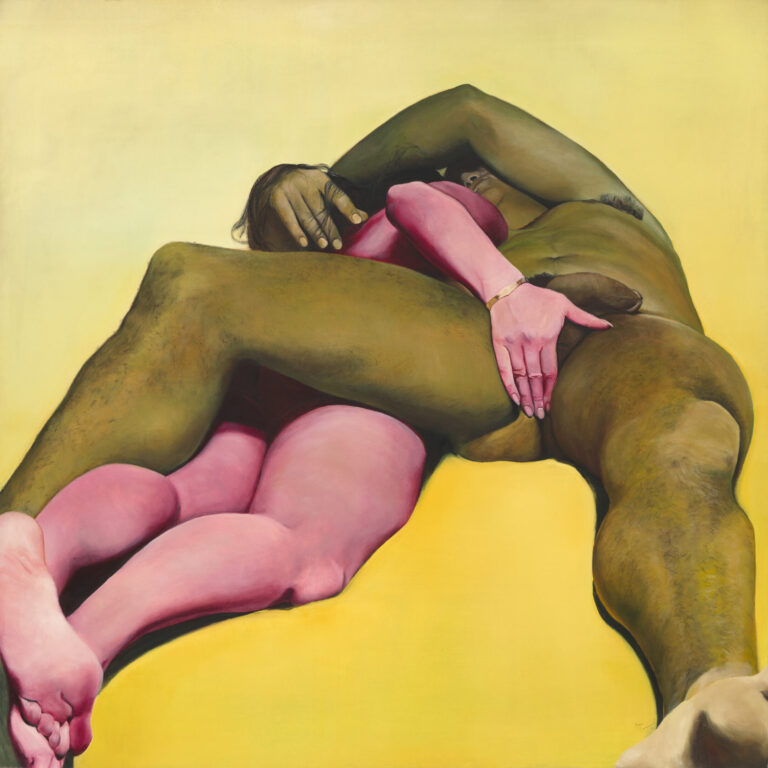

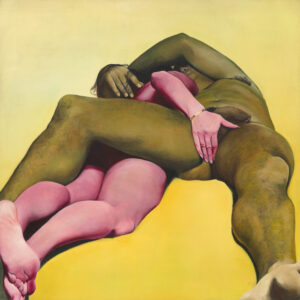

David Pagliarulo, David Peter Francis

As a teen in Tampa, David Pagliarulo spent many an afternoon giving feedback to a painter friend. “We were kind of doing studio visits,” he recalls. When asked what might have sparked this proto-gallerist behavior in his adolescent self, Pagliarulo reckons that he’s “always been the person willing to get on the train regardless of where it’s going. Like, Tell me the crazy, weird idea. I just want to talk through it.”

Less than a decade later, that big-hearted nonchalance has earned him the trust of quite a few artists. After earning a master’s in visual and material culture at the American University of Paris, Pagliarulo hopped on a plane to New York in 2018 to interview for an internship with Fort Gansevoort. He got it on the spot. The chance to see a gallery come to life arose when Clara Ha, a former partner of Paul Kasmin, opened Chart and tapped Pagliarulo as her second in command. Later, a director position at Marinaro—which had already built up a solid roster of artists—completed the arc of his gallery education.

An artist at the Tribeca gallery had “the crazy, weird idea” that would land Pagliarulo in an East Broadway space with his name on the lease. In October 2021, he was Ubering to a post-opening dinner with embroidery doyenne Elaine Reichek “and she just grabbed my hand and said, ‘You know, you could do this yourself one day.’”

“A lot of goddamn emails” later, David Peter Francis has two openings under its belt. What’s already clear is that Pagliarulo is drawn to peripheral viewpoints and category-allergic artists. The 28-year-old gallerist attributes this penchant for soft-power risk to the same urge that pushed him to strike out on his own. “There’s not a lot of history behind me,” he says. “Maybe in a couple of years I would have been more afraid to take the jump, [but] I’m walking into this less encumbered.” Of course, the temerity of youth comes with a price. “It’s easy to dismiss someone younger,” he acknowledges with a laugh. “I guess aging is the natural solution to that problem.”

Cierra Britton, Cierra Britton Gallery

“There are times when I think, Damn, should I just get a 9-to-5 on the side so I can at least have some guaranteed income?” says Cierra Britton. “Then I remember that when I did have one, I meditated on my lunch break every day, like, One day I’m going to have a gallery, and it’s going to look like this. Now that I’m in that position, I never want to take it for granted.”

Eight years ago, the Baltimore native took a class at the New School called “The Art of Viewing Art,” which introduced her to New York’s gallery scene. Jack Shainman Gallery became a pilgrimage site. “I would go every week, even if the same show was up," she says. "It was the gallery in Chelsea [with the most] Black art and artists that I had seen at the time." Even while she working at the Wing (yes, that infamous employer), she began to sketch out her plan to spotlight the artists she surrounded herself with in her own space.

A fellowship with Artnoir, a stint in art advising, and a seminar with the entrepreneurial platform IFundWomen all proved essential in helping Britton concretize that goal. Thirty thousand crowdfunded investment dollars later, in 2022, she opened her first pop-up SoHo show, a painterly meditation by Jewel Ham on the Black femme experience. That exhibition announced two key elements of Britton’s current program: its roving nature and its commitment to “creating a safe and much-needed space for BIPOC womxn artists.”

Now 27, Britton is awake to the reality this model has bestowed on her. Being the only gallery in New York with a focus on this cross-section of artists has spiked curiosity and a deep well of community support. But Britton knows white men sell more, for more, and that there are some boys’ clubs she will never get the keys to. “I’m happy to take the gamble because it’s way bigger than me,” she concludes. “I want this industry to get to a place where women and nonbinary people are not an afterthought, and where people of color are not a trend. This is me trying to change up the conversation.”

Caio Twombly, Amanita

If it weren’t for Italy, Caio Twombly might never have opened a gallery. After stints in London and New York, where he’d already curated a handful of shows, the pandemic brought him back to Rome. In his hometown, he began to take stock of the Italian scene, which could feel like an antonym in and of itself. “My friends and I always say it’s impossible to be contemporary in Rome, because everything has already happened,” he says over the phone.

Twombly took the country’s sleepy status in the contemporary art world as a challenge. He wasn’t the first in his family to find resolution in Europe’s boot: His grandfather Cy exiled himself from the New York scene in the late 1950s, spending the rest of his prolific career there. Together with his pal Tommaso Rositani Suckert, Caio opened Amanita—an outfit dedicated to highlighting the living Italian artists he’d uncovered—in Florence, during the summer of 2021.

“That space in Florence feels like the prepubescent stage of what Amanita is now,” he says. The seat-of-the-pants ethos of the gallery’s early years—“the North Star was, Let’s have fun and see what happens”—has given rise to today’s built-out roster of nine represented artists and four partners (Twombly and Rositani Suckert were joined by Jacob Hyman and Garrett Goldsmith in the fall of 2021). And a New York gallery, in CBGB’s old digs on the Bowery, has eclipsed the Tuscan location. “If I really want to do something significant for Italian artists,” Twombly muses, “paradoxically, I have to do it in New York.”

Bolstering the artistic careers of others has meant that Twombly has often had to put aside his own “timid practice,” a sacrifice that has, on occasion, led him to question the path he chose. But at 27, he seems to have outgrown those insecurities—a sign that being green doesn’t preclude levelheadedness. “The doubts from before pale in comparison to the responsibility, energy, and ambition we’ve managed to generate,” he says. “That guides us now.”

in your life?

in your life?