I am not a carbon copy of anyone, just as you are not a composite of your mother, father, grandparents, siblings, or extended relatives. The self-portrait you see—the image of your presence—will be the life you live. Part of the root of the word photograph is phōs, which means “light” or “to shine.” It appears also in the ancient Greek word phōsphóros, which means “bearer of light” or “bringer of light.” To photograph means to draw with light. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

In 1982, I was born by the ancient Monongahela River in Talbot Towers, an Allegheny County public housing project in a neighborhood known as “the Bottom” in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Shaped by the steel industry and the legacy of the nineteenth-century industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, it is home to his first steel mill, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works (1875), and his first library, the Braddock Carnegie Library (1889).

From the Steel Valley, along the Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers to the Flint River in “Vehicle City,” Flint, Michigan; from historical mineshafts in the Borinage, Belgium, to a historic labor union in Lordstown, Ohio; and from community health workers in Baltimore, Maryland, to a labor leader and civil rights activist in California’s Central Valley, I’ve used my camera as a compass to direct a pathway toward the illuminated truth of the indomitable spirit of working-class families and communities in the twenty-first century.

For this reason, it is incumbent upon me to resist—one photograph at a time, one photo-essay at a time, one body of work at a time, one book at a time, one workers’ monument at a time—historical erasure and historical amnesia.

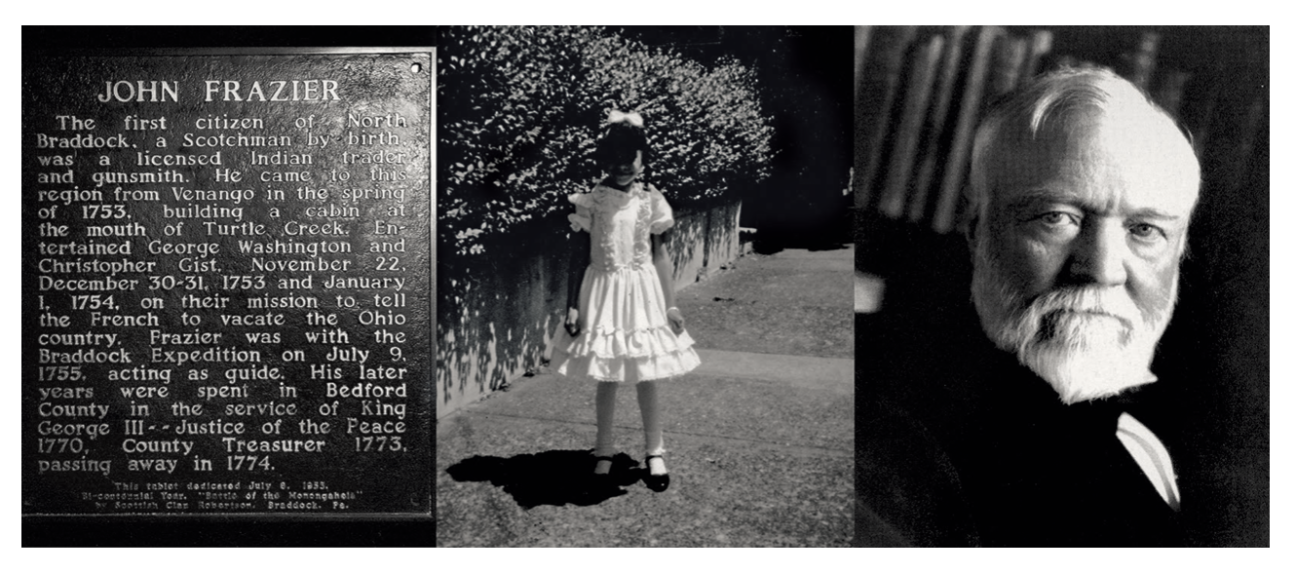

My spiritual bondage to Braddock was broken the instant light exposed my film’s silver halide crystals as I created United States Steel Mon Valley Works Edgar Thomson Plant (2013), hovering over the city with a bird’s-eye view. Permeating the twenty-first-century postindustrial landscape were the vestiges of imperial war, patriarchy, and the death and destruction of nature. Braddock is a namesake of the British general Edward Braddock, who was defeated and mortally wounded at that site in the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755. George Washington, who served as one of Braddock’s aides-de-camp, had earlier witnessed the onset of the imperial war between Great Britain and France—the French and Indian War of 1754–63.4 John Frazier, who aided Washington, served in expeditions against the French. A plaque at the Edgar Thomson Steel Works marks the spot where his cabin once stood.

In the triptych John Frazier, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Andrew Carnegie (2010), which includes a picture my Grandma Ruby took of me, I pose a question: Weighed against the two colossal Scotsmen that dominate Braddock’s history, what is the value of a Black girl’s life?

On the same battlefield, two and a half centuries later, I created a self-portrait, Grandma Ruby, Mom, and Me (2009), standing inside Watt’s Memorial Chapel. It is evident to me that we are fighting not only a physical war but a spiritual one. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil, for You are with me.

Self Portrait October 7 (9:30 a.m.) (2007) documents my battle with lupus. Like photosensitive film and paper, the medications make me light sensitive. I’m one with my medium.

Huxtables, Mom, and Me (2008) is awareness of the American caste system and conflicted social mobility. The first thing an artist finds out . . . before he or she has had enough experience to begin to assess his or her experience . . . is a kind of silence. For reasons he cannot explain to himself or to others, he does not belong anywhere.

Momme (2008) is a refusal to remain silent about the abuses I could no longer endure within my matrilineage. You’re bearing witness helplessly to something which everybody knows and nobody wants to face. For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. When life and shame and sorrow occlude our own light from our view there is still a clear-eyed loving person to beam it back.

The artist is distinguished from all other responsible actors in society—the politicians, legislators, educators, scientists, et cetera—by the fact that he is his own test tube, his own laboratory, working according to very rigorous rules, however unstated these may be, and cannot allow any consideration to supersede his responsibility to reveal all that he can possibly discover concerning the mystery of the human being.

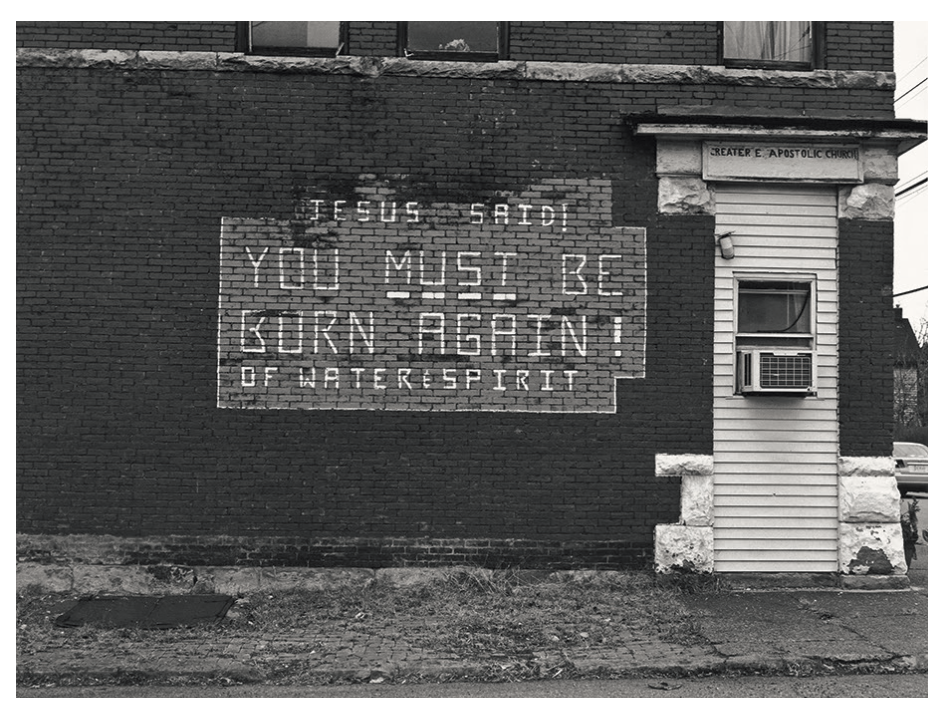

Born Again of Water and Spirit, Ninth Street and Washington Avenue (2009) documents the demarcation line between the Monongahela River, Talbot Towers, and 805 Washington Avenue, the house where Grandma Ruby raised me. Society must accept some things as real; but [the artist] must always know that the visible reality hides a deeper one, and that all our action and all our achievement rests on things unseen. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.

I asked my mentor Kathe Kowalski, “If you’re no longer here, how will I know if I’m making strong work?” Her reply was the last thing she said to me: “You’ll know because your photographs will speak back to you and start to take you places.” For our knowledge is fragmentary (incomplete and imperfect), and our prophecy (our teaching) is fragmentary (incomplete and imperfect).

When I see Dorothea Lange’s 1936 photograph Migrant Mother, I see a structure of power: government first, corporation second, commissioned photographer third, subject/sitter fourth. I’ve sought to invert this power dynamic in order to create a paradigm shift.

Gordon Parks’s use of his camera as a weapon against racism, intolerance, and poverty throughout the twentieth century made it possible for me to use my photographs as a platform for social justice, equity, and cultural change in the twenty-first century.

In 1981 Martha Rosler wrote, “The documentary of the present, the petted darling of the monied, a shiver-provoking, slyly decadent, lip-smacking appreciation of alien vitality or a fragmented vision of psychological alienation in city and town, coexists with the germ of another documentary—a financially unloved but growing body of documentary works committed to the exposure of specific abuses caused by people’s jobs, by the financier’s growing hegemony over the cities, by racism, sexism, and class oppression, works about militancy, about self-organization, or works meant to support them. Perhaps a radical documentary can be brought into existence.” For twenty-five years I’ve been building a practice, an archive, a library, and monuments of workers’ thoughts to answer Martha’s call.

When I was called to Flint, the first time I photographed Shea Cobb’s daughter, Zion, I knew she was spiritually assigned to me. What I couldn’t do for myself when I was an eight-year-old girl in Braddock facing a similar water crisis, I fulfilled in Zion’s circumstance. Flint Is Family In Three Acts (2016–20) is the platform on which Zion can stand if she ever loses her way, to remember that she is not a victim but a victor. No weapon that is formed against thee shall prosper.

From Allegheny, the best flowing river of the hills, to Genesee, the pleasant valley, I was called to aid Amber Hasan as she set her face like flint to secure a twenty-six-thousand-pound atmospheric water generator and protect her children, family, and community against the man-made water crisis in Flint.

When Shea saw the photograph Zion Taking Her First Sip of Water from the Atmospheric Water Generator with Her Mother Shea Cobb on North Saginaw Street Between East Marengo Avenue and East Pulaski Avenue, Flint, Michigan (2019), she texted me, “Thank you for the light that you bring to my city.” I replied, “The light was already there within you.” The eye is the lamp of the body. No matter how dark a situation may be, a camera can extract the light and turn a negative into a positive. It is necessary, while in darkness, to know that there is a light somewhere, to know that in oneself, waiting to be found, there is a light. What the light reveals is danger, and what it demands is faith.

To the Lenape people, monongahela means “where banks cave in or erode.” It is said that to the Algonquin tribe, housatonic means “place beyond the mountain.” The color aerial photographs installed like maps in my 2013 series A Despoliation of Water: From the Housatonic to Monongahela River (1930–2013) were inspired by W. E. B. Du Bois’s words: “The town, the whole valley, has turned its back upon the river. . . . They have used it as a sewer, a drain, a place for throwing their waste and their offal. . . . We have crossed it with bridges of unbelievable ugliness, we have choked the flow of its waters.”

When I was called to work with coal miners by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation’s Museum of Contemporary Arts (MACS), which sits inside the former Grand-Hornu colliery, the men said, “You’re a woman, you’re American, you’re Black. Why do you care about us?” Then they stated, “Contemporary art is useless. The MACS doesn’t care about us.” I knew then and there that I was called to stand in the gap between the working and creative classes. Van Gogh, who served in the Borinage nearly a century and a half before me, in the coal mine I photographed in Charbonnage de Marcasse, Wasmes, Borinage, 13 Octobre 2016, is depicted there in a mural as a priest, artist, and coal miner.

I was received into the historic United Auto Workers Local 1112 to document their fight for a new product at the unallocated General Motors plant in Lordstown. With the photograph Prayer Service at the Cortland Trinity Baptist Church for GM workers, their families, and Trumbull County region (Dave Green, Pamela Brown, Norm Perry, and Dave Hake receiving prayer from Pastor Dan Barker), Cortland, OH, 2019, I lift them up in prayer, weep with those who weep, and rejoice when right and truth prevail.

Yet in all these things we are more than conquerors and gain an overwhelming victory through Him who loved us. In More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland 2021–2022, what’s monumental is not a singular image of a man but the form of love enacted in times of great sorrow by those whom we choose not to perceive. Community health workers bravely stood on the front lines throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and they continue to do so, to this day, without adequate compensation or recognition.

The portrait Sandra Gould Ford in Her Office in Homewood, PA (2017) exalts its subject as a wise knower, not only of the process of steelmaking but also as the North star for the steelworkers at Jones and Laughlin Steel Company. As she stands before the solar system, with the Milky Way galaxy appearing to flow from her eyes, I imagine what Arjuna saw when Krishna granted him cosmic vision.

The monument A Pilgrimage to Dolores Huerta: The Forty Acres, Arvin Migratory Labor Camp, Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, Dolores Huerta Peace and Justice Cultural Center (2023–24) honors the devoted labor leader and civil rights activist as a beloved mother and grandmother. Seeing herself in all beings and all beings in herself, she is agape love in action.

May the eyes of your heart be flooded with light so that you can know and understand the hope to which you’ve been called. For we walk by faith, not by sight.

in your life?

in your life?