For Idris Khan, there’s beauty in repetition. Growing up in a Muslim household in the U.K., the London-based artist followed his father’s religious devotion. “We were praying together, but I never really knew why I was doing that. I never knew the language; I sort of just repeated.”

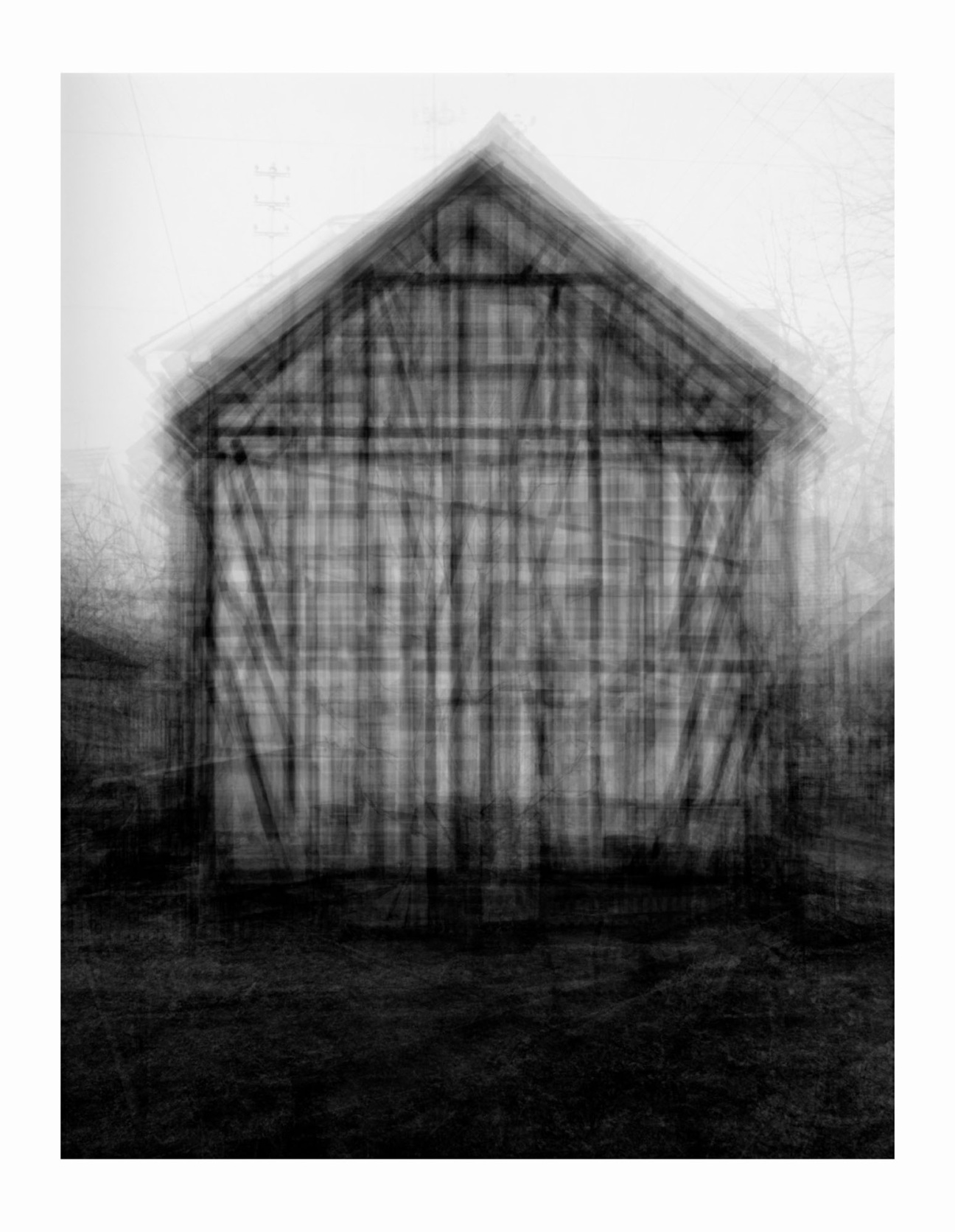

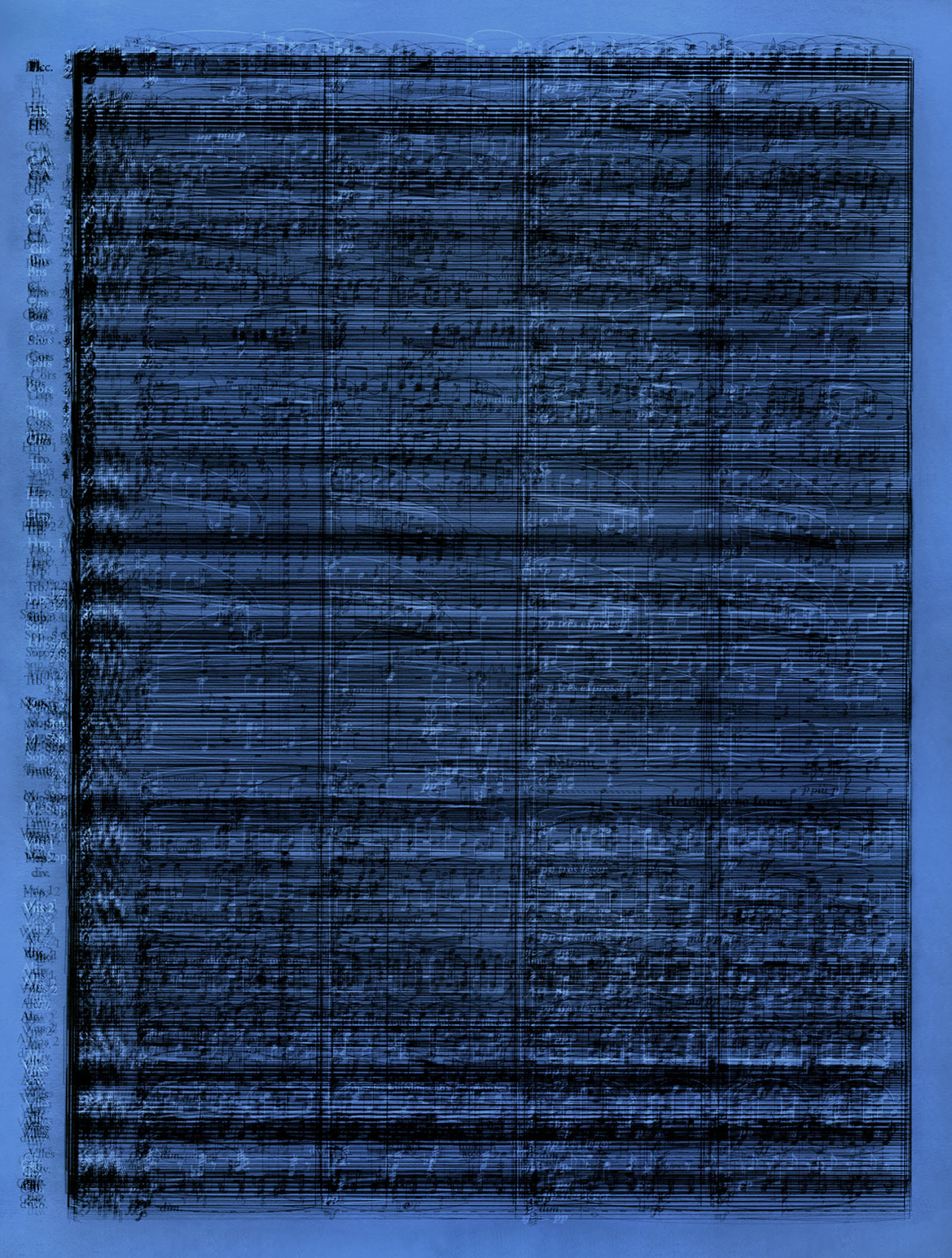

Iteration is now a lifelong investigation, and the main subject of his first solo U.S. museum show “Repeat After Me,” on view at the Milwaukee Museum of Art. The title is a mantra from Khan’s father: “‘Repeat After Me’ came from what he used to say to me in the mosque.” Viewers can see this fascination in the looping scrawl of Bicycle Wheel…after Duchamp, 2014, and the overlapping staffs in Bach…Six Suites for the Solo Cello, 2006. And in the new work created expressly for the exhibition, Khan continues to seek the beauty and constraint in the ritual of repetition.

Here, Idris Khan revisits the key moments and figures that paved the way to this mid-career survey. From the early support of Victoria Miro, who funded his first studio, to Charles Saatchi climbing four flights of stairs to view his work at the Royal College of Art, Khan has accumulated devoted champions and a generous perspective on the two decades of work present in the Milwaukee show.

CULTURED: Your first museum solo show in the U.S. opened last week. How does it feel?

Idris Khan: It’s not every day that a 44-year-old British artist gets an American museum show. It’s quite rare. But I’ve always shown in America and been very well supported by American collectors. I was a product of the real boom in art fairs if I really think back to it. I started working with Victoria Miro straight out of college, and she showed me at Art Basel Miami Beach around 2006.

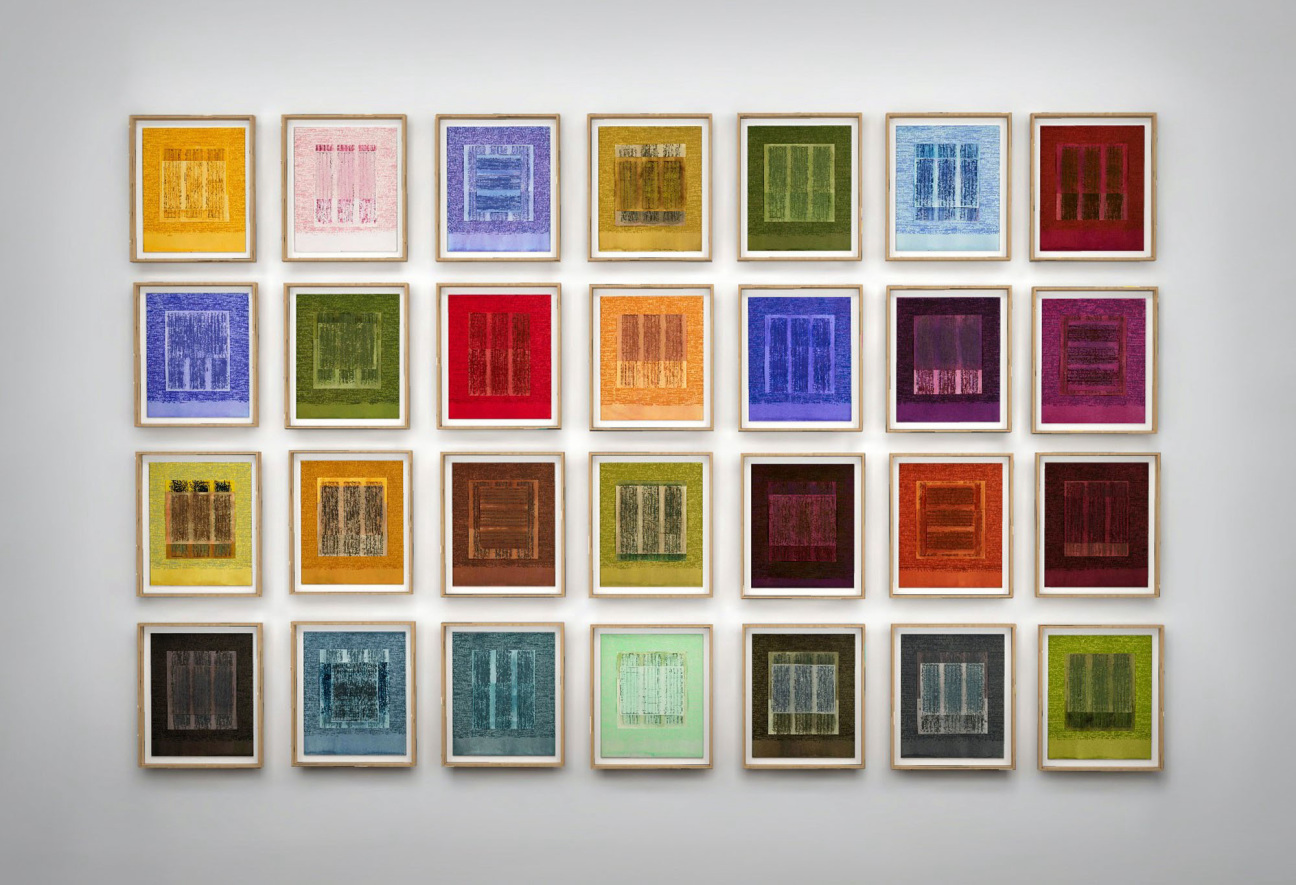

I’ve been introduced to the commercial public for a long time in the States. The show was [first] discussed around six years ago; because of Covid everything got messed up, but in a really positive way because it allowed me to fill the last four rooms of the exhibition with a new body of work involving a lot of color … I’d mainly done commercial exhibitions where you can change things as you go, but in a museum, everything is built around the work. It is what it is. And as soon as you put text on the wall, it gives such gravitas to work. It slows people down, and you see it differently too.

CULTURED: What initial reactions to the show have touched you? Have any surprised you, or shed new light on your work?

Khan: The first amazing reaction was when I walked my gallerist Sean Kelly around. He was very, very cheerful and proud to see my journey unfold in the exhibition … I always ask myself a series of questions before I embark on any body of work, which lead to subtle shifts that look like massive ones [in the context of the show]. I was looking at this massive sculpture called Overture, 2015. It’s a sculpture with glass and white stamped words over the surface. I had never noticed that it actually looked like the bellows of the camera opening up. I haven’t seen a lot of these works for a while because they’ve been in collections, et cetera. Seeing the links from early photography and how it still holds up is crazy. Most of those early photographs were from my degree show at the Royal College in 2004.

CULTURED: What was it like to re-encounter that earlier version of yourself as an artist when you were sifting through your archive for the show?

Khan: It was kind of beautiful because it positioned me back at the making point. We walked around Milwaukee, and we looked through a window, and students were preparing to put up their degree show work. I pictured myself doing that 20 years ago and not knowing anything—not knowing whether you're going to have a career at all, thinking about whether you’re ever going to get a studio. When Marcelle [Polednik] and I first talked about the show, it wasn't supposed to be this big. She had a couple of bodies of work in mind, but as we started talking it grew with the post-Covid body of work.

Going through the show reminded me of working on my shitty computer, riding my bike with my rolled-up prints, going to a specific printer… Things change: You get a bigger studio, people help you a bit more. But those stories about growing as an artist [are so important]. Like showing up to Victoria Miro’s office with a box of prints and saying, “What do you think of this?” Or Charles Saatchi walking up four flights of stairs to see my studio at the Royal College of Art when he was slightly bigger and being exhausted at the top. The elevator was out, and he said, “This better be fucking good,” and then buying the work. It sparks these wonderful memories of the creation of the work rather than where it went on to be. Why you did it in the first place.

CULTURED: I’d love to describe the ecosystem from which the new body of work springs. What was the spark for that?

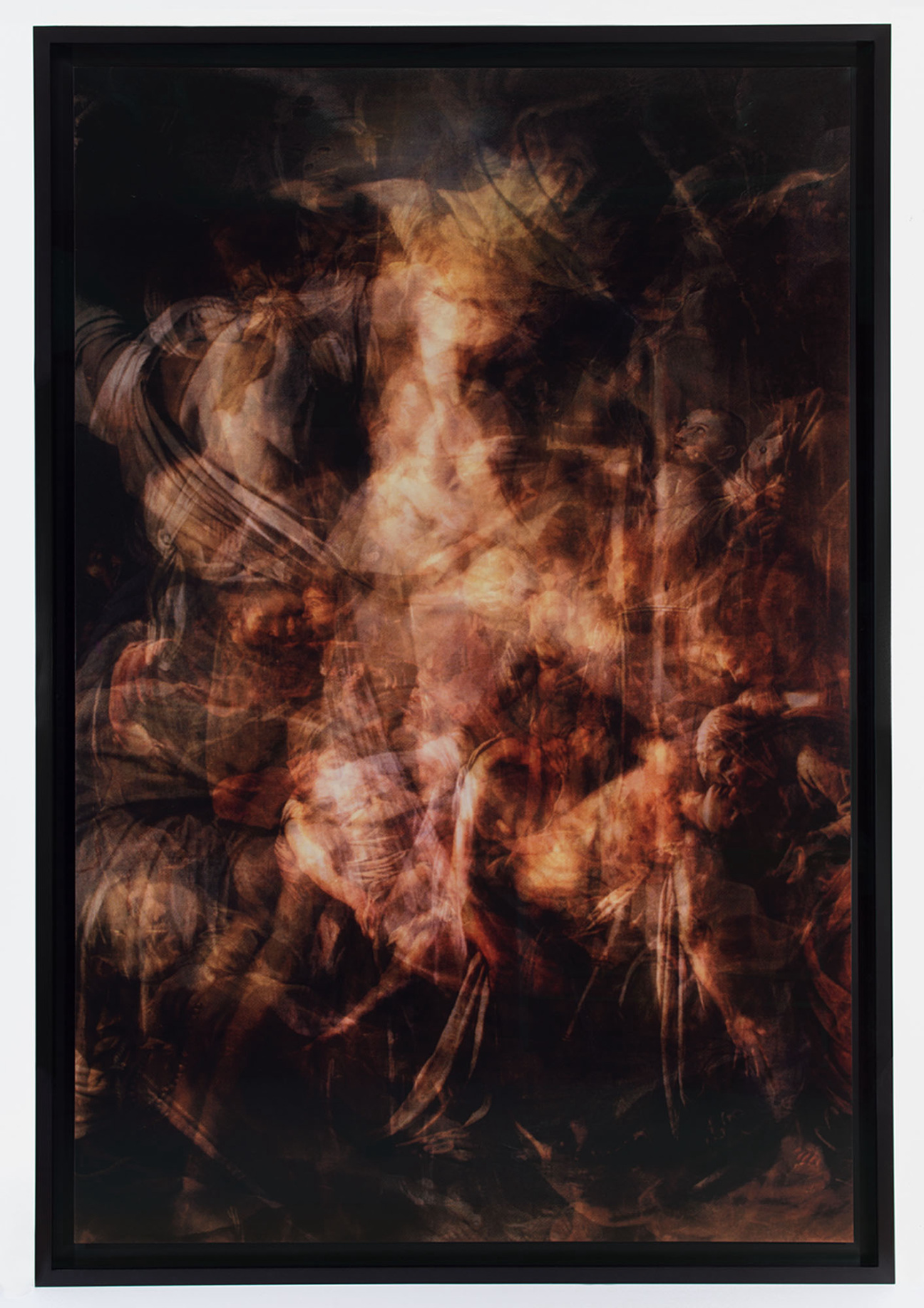

Khan: “The Seasons Turn” is the body of work I left Covid with, which marked that year in color. At that time, Annie [Morris, Khan’s partner and fellow artist] and I went out to the countryside in England and stayed in an Airbnb. The seasons and the colors felt really vivid—the sky, the sprouting flowers, whatever it was. For that body of work, I needed something to grasp onto. I looked back at how I used appropriation in my early photographs. I started to think, Well, I’ve got major paintings that I love. That we all love, really.

The real trigger points in the new body of work are memories of paintings. For example, standing in front of the Mona Lisa, 1503-06, or The Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665, and taking it back to its palette, stripping the painting down and bringing it to these simple grids. I would scan the reproductions of the paintings and use this program that positions musical notations with volumes of color and tone to the art. It’s sort of like you’re listening to the sound of a painting, which is where this work will develop [in the future]. I then use those notations to dampen onto the surface of my grids and play with watercolor and collage on top for variation.

One painting [in the Milwaukee Art Museum] called Saint Francis of Assisi in His Tomb by Francisco de Zurbarán inspired my piece called The Tomb. The Zurbarán painting is very famous in Milwaukee, so I wanted to do something in reference [to it]. There's also a beautiful verticality to that image. It's not massive; it's pretty ghostly, with a monk figure in the center, which I saw as an escalating shape. I made this piece with eight works that feel tall and big on the wall.

CULTURED: We’re talking about paintings that have left a trace on you. Can you discuss what people and artists have been crucial conversation partners for you over the years?

Khan: I got into art through education. There was nothing in my family to do with art. I did a foundation year, I studied photography at University of Derby, then came down to the Royal College of Art. I have so many peers and teachers to acknowledge. There was one guy called Oded Shimshon, who was an amazing photographer and really guided me in making mural photographs. My other teacher, John Stezaker, was a massive influence on how I think about appropriation in collaging, cutting, and layering.

Then of course Victoria Miro paid for my first studio before my first show with her and continued to support me that way. Yvon Lambert, who was my dealer in Paris. On the day he retired after 50 years, Sean Kelly called and said I really want to work with you. And I have to thank Annie Morris for influencing me and making me work hard. There are so many stages and opportunities to keep making art. You sell a piece, you want to make the next one, and it’s that lovely journey that I can credit to so many people.

CULTURED: The word "repetition" is often linked to your practice, even in the title of the Milwaukee survey, which is called "Repeat After Me." When I think of your work, the words “excess,” “accumulation,” and “patience” also come to mind. Your work rewards the patient viewer.

Khan: When I started making photographs, I was frozen. I didn't want to create pictures because there were too many pictures in the world—there was an explosion of digital imagery in the early 2000s. I thought to myself, I don’t want to make any new photographs, I want to look back at what’s been made. So there was a work that was made from every photograph I’d taken while traveling around Europe, and another from all the pictures I took on top of the Empire State Building. It was about compressing the volume into one moment in time.

In the Milwaukee show, there’s a work called 65,000 Photographs, 2019. There was one day, I looked at my phone and had 65,000 pictures. I asked myself, What are you gonna do with these pictures? You're never going to print them; what does that look like in terms of volume? So I printed 65,000 photographs and made a sculpture. It makes you think about the edges of the paper and the edges of time. There's another sculpture called My Mother, 2019, which is made up of 340 photographs, which was just the volume of time of her life. She passed away when she was 59, and the volume of time in this small sculpture compared to the crazy number of pictures we take… We're never going to do anything with them, but they exist. I have a picture of my kids every single day of their lives; it’s bonkers. There's an overload of information all the time. Then you look at my paintings with the words, and you can think about your own relationship to language.

"Repeat After Me" is on view through August 11, 2024 at the Milwaukee Museum of Art

in your life?

in your life?