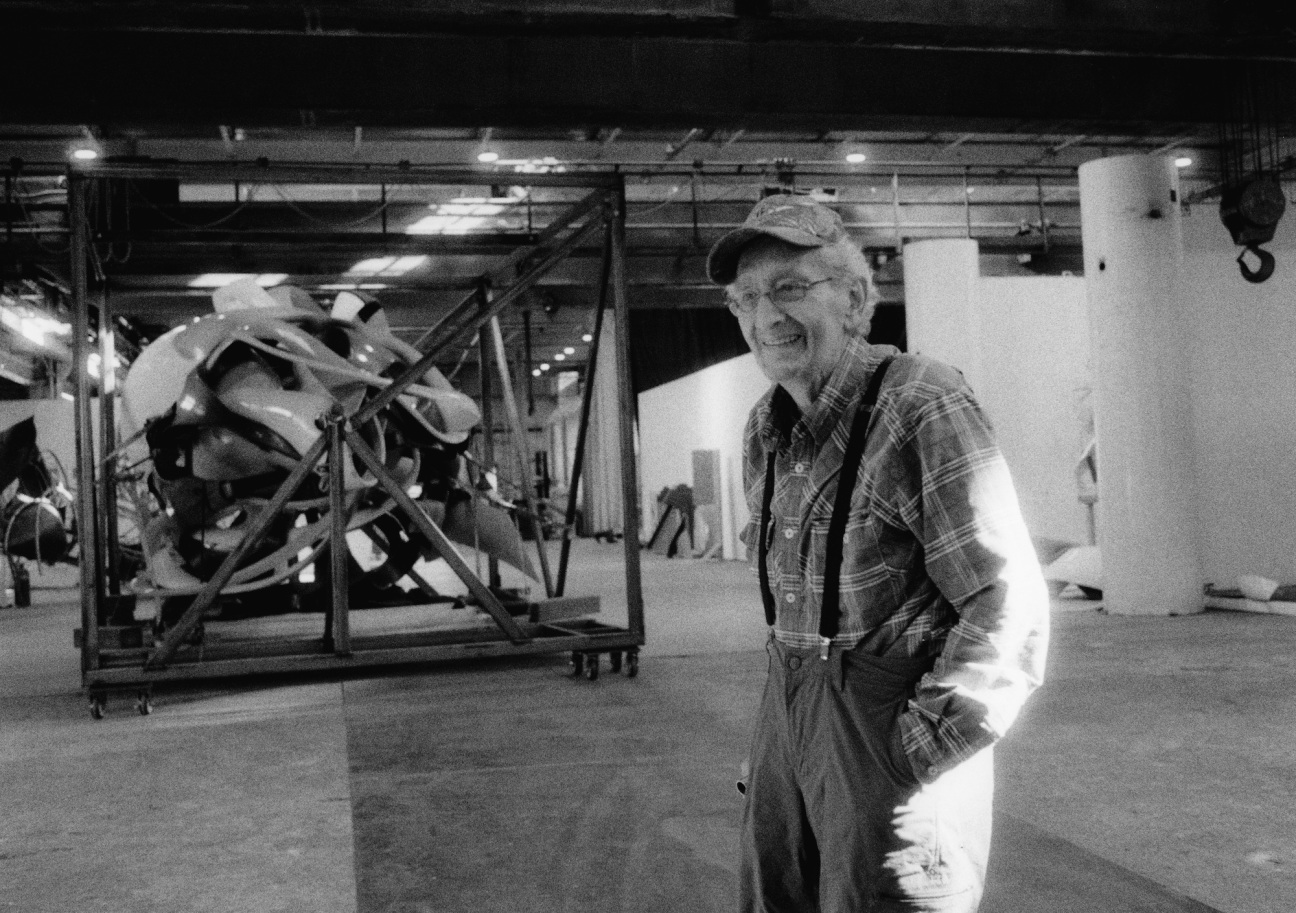

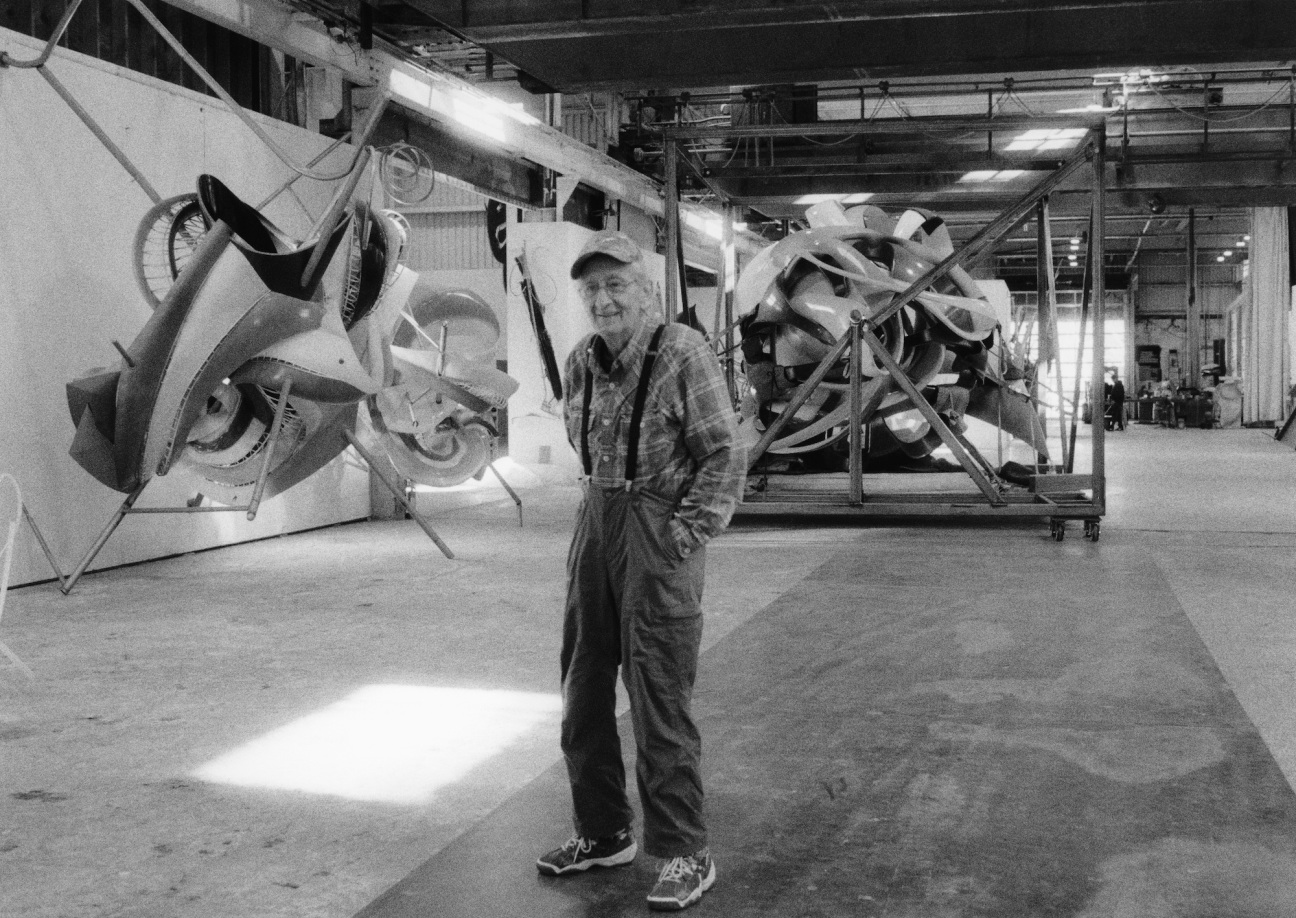

“When I first came up with the New York people, I was considered right off the bat a truly academic painter,” says Frank Stella with a chuckle. “I think they still think that.” Sitting among the versicolor aluminum and fiberglass constructions in his studio in Rock Tavern, New York, the 87-year-old artist is laconic and given to soft, self-deprecating laughter.

In preparation for his latest New York solo show, all but one of the five large-scale sculptures (“they're not monumental, they’re big,” the artist qualifies, pace the gallery’s press release) have been delivered down the Hudson, via the Manhattan bridge at night, to Jeffrey Deitch’s Wooster Street space. Padded with moving blankets and strapped to a heavy-duty industrial dolly, the remaining piece, K.40 Large Version, 2014, is a farrago of whiplash curves in white and aquamarine fiberglass, ensnaring an orange and purple core. Its Cthulhu geometry demands circumambulation and evangelizes complexity.

Obviously, we are galaxies away from the pithy deductive structures and logo-like late modernism that launched Stella’s star more than 60 years ago. I ask the artist whether his famous adage—“What you see is what you see”—still holds against the gestural flamboyance and non-Euclidean maximalism he has pursued to increasing degrees since the ‘70s. “Each person involves themselves [in the work] in one way or another,” he replies. “So I think that that’s true still. I mean,” he laughs, “how could it be anything else?”

The assertion of continuity seems to gloss over a not-inconsequential shift. Once taken as an assertion of perceptual immediacy and epistemological clarity, “What you see is what you see” now expresses something closer to a devil-may-care subjectivism. Other blithe tautologies spring to mind—“I like what I like.” “You do you.”

K.40 belongs to Stella’s “Scarlatti Sonata Kirkpatrick” series, whose numbered titles come from the harpsichord sonatas of Italian Baroque composer Domenico Scarlatti, all 555 of which were cataloged by musicologist Ralph Kirkpatrick in the 1950s. “I don’t have much of an ear to say the least,” Stella tells me, “but I like Scarlatti a lot.” The sonatas, furthermore, “had one big advantage: There were a lot of them. So they supplied a lot of titles.”

Stella’s ribbon-like forms, achieved in high density foam covered in fiberglass, begin as computer models that then become 3-D printed maquettes; these are shipped to fabricators in the Low Countries, who construct the full-scale sculptural elements that are finally transported back to Stella’s studio upstate, where they are assembled and sprayed with automotive paint. Several other works in the Deitch show, which belong to the “Atlantic Salmon Rivers” series (2021–23), are made according to a similar process, sometimes in aluminum. Suspended from metal armatures, the twisting biomorphic planes of The Grand Cascapedia, 2021, and The Kedgwick, 2022, evoke fish caught on a line.

Stella was an early adopter of digital fabrication; he began using computers to render waves for a Dutch commission in 1990. Yet he invests little faith in technology as such, viewing it instead as a means to an end. “If you’re building a piece that’s larger than what you can build with your own hands, you have to present it in such a way that the people who are gonna build it will do it,” he explains. “It was their idea to use the computer, not mine.” He waves away the notion of the “technological sublime”—a formulation the art historian and critic Caroline Jones has brought to his work—and is admittedly bewildered by the disruptive implications of generative AI. “First of all, I don’t understand it,” he says, “And secondly, it doesn’t move me very much to try to understand it.”

As for what is inspiring him now, Stella says he’s “remembering art more than looking at it” these days. He still “get[s] hung up a lot on [Vassily] Kandinsky,” particularly the painter’s once disparaged late work, with its decorative profusion of embryonic, ameboid, and otherwise organic forms. The comparison to Stella’s recent production is hard to resist, and I ask him if he has any thoughts on the vexed notion of “late style” (think of the reckless, freewheeling abstraction of the mature Titian, Turner, Monet, Twombly). “No, I hope I don’t,” he concludes. “I don’t have any thoughts about what I’m doing now, except that I try to do it. Some things seem kind of edgy, and then some things are kind of surprising. They seem to have room to move around. There’s a lot of opportunity out there.”

"Frank Stella: Recent Sculpture" is on view at Jeffrey Deitch in New York through April 20.

in your life?

in your life?