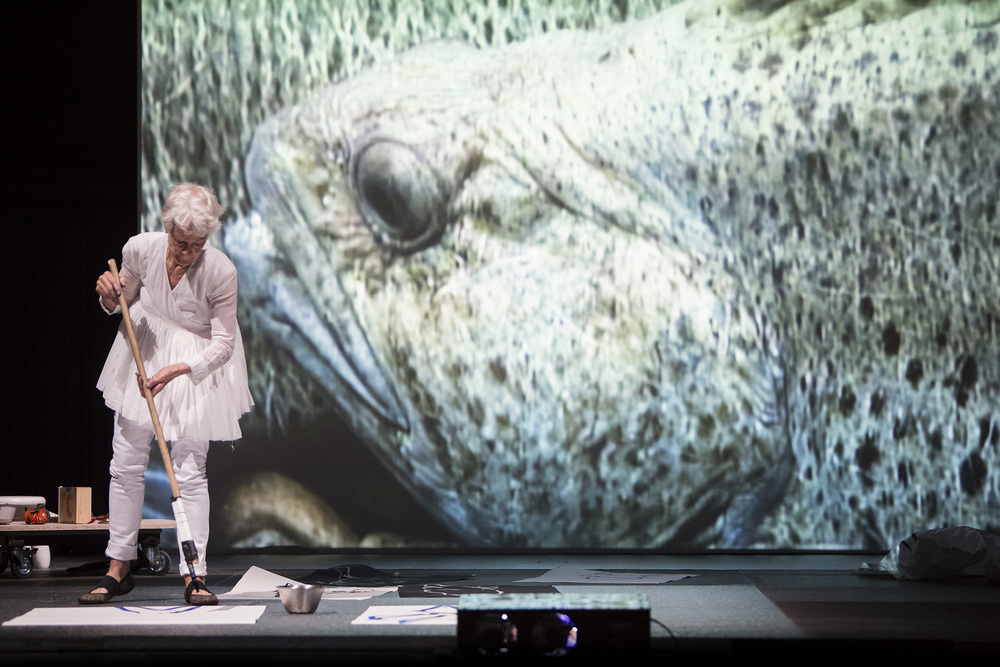

For six decades, the artist Joan Jonas has diligently defied any notion of completeness in her kaleidoscopic oeuvre. The 87-year-old continually revists her recordings, large screens, drawings, and photographs, offering those who’ve followed her a refracted experience as she layers elements of previous work, building her own geology. Past and present allide across film footage, convex mirrors, and props—sticks, flags, kites, even a taxidermy coyote—in the sonic surround of her music and vocals.

A new generation will have the chance to discover her work when her most comprehensive U.S. retrospective to date, “Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning,” opens at MoMA later this month. For the uninitiated, Jonas’s methods can be challenging. I’ve regularly been asked, what does her art mean? But if you surrender to it, Jonas’s performances are a spectacularly strange, hazy overload—an unfurling conceptual fairy tale. Jonas may be dancing, wearing a mask, cavorting with a bucket, or painting a big snake on the floor—all silhouetted by scrolling projected images. She may even add her white poodle Ozo to the mix. As the artist herself advised in a 2018 New York Times article about art that initially confounds her: give yourself up to the work and try not to make sense of it right away.

Jonas, who represented the U.S. at the 2015 Venice Biennale, is also known for expansive artist collaborations, and perhaps none quite as intimate as her four performances and longstanding friendship with jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran. He has bridged his own divide between visual and musical art with his sculptural installations of storied music venues, like the Savoy Ballroom and The Three Deuces. (I profiled Moran for CULTURED in 2018 on the occasion of his Walker Art Center exhibition.) Back in 2005, however, Jonas wanted to expand her immediate circle of composers. Artist Adam Pendleton suggested Moran, and they went to hear Moran play a piece called Rain commissioned for Lincoln Center, after which Jonas simply looked the musician up in the New York phone book and cold-called to see if he would be interested in working together.

Several weeks ago, I sat down with both of them to reflect on their 20-year exploration and find out what’s in store for their latest performance, A Lecture Demonstration, which debuts later this month at MoMA.

CULTURED: How has your artistic relationship evolved since your first project together, The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things, almost 20 years ago?

Joan Jonas: That summer in 2005, when Jason and I began to work together, the Dia Art Foundation gave us six weeks to rehearse in the space, which is very unusual for an institution. We went up to Beacon every weekday. Jason said he was just exhausted after it. We began by talking about how we would work together in the performance: I would bring the structure and the video, and Jason and I worked together to choose the music. He would play motifs and pieces that he had composed, and we would decide which to use. So far, we’ve done four performances and works in collaboration. As a jazz musician, Jason has really opened me up in terms of improvisation.

Jason Moran: When we started together, we were not even looking at a word like collaboration, because it felt—at least, from my point of view, making the music—more functional. Then, over time, as Joan was describing, the language of the performance really started to become one language, rather than, the music does this; the costume does this; the film does this; the text does this. Now, the performances blur the spaces between these elements.

CULTURED: What about on a personal level? How have your lives intertwined?

Moran: Well, my entire family has worked with Joan at some point: my wife [mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran], my twin boys, Malcolm and Jonas. I never anticipated this close, enduring friendship. When I first met Joan, I was a pianist and had no idea what I was about to learn from her all these years later. Joan was talking about folk music in America; she would ask about folk melodies transcending genre, location, and time. My creative evolution is massive because of the relationship we have. In 2006, I recorded the album “Artist in Residence,” and I felt Joan had to be part of this canon I was making in the Jazz world. It was a really powerful moment when we first gathered together at Dia Beacon, and we’ve gone so many places since then.

Jonas: I started working with Jason’s kids when they were around five or six. They’re young adults now, and they were just wonderful as children. I only had to say to them, “Walk around,” or give very simple directions. But I’m doing a new piece for my MoMA show, "Good Night Good Morning," and I wanted to have several dancers. I know that Jason’s son, Malcolm, is studying ballet, so he has come back into my work, which I really enjoy.

CULTURED: How much direction for performers is there generally in your collaborations?

Moran: Joan will tell you, “I just say a few things.” But you have to understand: she just says a few things, so you have to kind of get it. Watching Joan over the years has helped me understand how to give direction to someone who might not quite understand all the history of the work, but can get into the action. It has always been helpful watching her direct others to see what kind of cue points she gives to push them forward. What also strikes me about Joan is that she always works across generations. She asks for everybody’s input, and she really wants to know. She’ll tell people, “Go stand there. Let me look at it for a second. Now how do you feel standing there?” I work with some people who don’t deeply care about their collaborators the way she does.

CULTURED: Jason, you now use pigment and paper to record your hand on the keyboard as you play. How are your piano rubbings a response to Joan, given how crucial mark-making—whether footage of her ice and ink drawings in Reanimation, 2013, or chalk on a blackboard in Lines in the Sand, 2002—is to her practice?

Moran: The big insight for me was watching Joan make live drawings in each performance, so the performance had something left behind. It was more than just a memory for the audience—there was an object, too. That pushed me towards thinking, What is happening in all of these clubs and festivals when I sit down at the piano? What’s not being recorded between the body and the instrument? The interaction between the two is something that could be animated and made visible. I’ve watched Joan make upwards of 1,000 drawings in a show while I’m playing. The relationship of my marks on paper and sonic paintings to my experience collaborating with her couldn’t be more direct.

CULTURED: Given the degree of improvisation, how do you communicate during a performance?

Moran: As a musician, I’m basically a listener. I’ve spent my entire life trying to hone that sensibility of when a moment is ready to move on. In Reanimation, we made a system of what I would call light musical cues. At a certain point, I’d say, “I’m watching Joan with this mask and this paper cape, and I think Joan is tired. I should prepare for the next phrase to move on.” Sometimes, from my point of view at the piano, I’m also watching Joan in relation to the image that’s on the screen. Sometimes those two images signal very clearly that it’s time to move on. Usually, though, no one said where the end is, we just have to arrive there together.

Jonas: I was just watching the performance They Come to Us Without a Word, 2015, and we do some very long improvisations, but we have the children dancing and I’m moving. It goes on for a long time. I was thinking, we never could have done that without Jason’s music. Music allows you to extend moments in a different way. That’s one thing that Jason’s involvement has really brought me. Jason has very subtle cues that I hear towards the end of a sequence. But then sometimes, I just maybe walk off and leave it to Jason to figure it out.

CULTURED: Here we are, five weeks before the debut of a new collaborative performance. What can you tell us about A Lecture Demonstration, which is part of Joan’s MoMA retrospective and will debut on March 26?

Jonas: This performance is not something that we will rehearse a lot. We’ll go through it a couple of times, because it’s a series of quotes from different performances that we’ve done together, rather than one unified piece. We’d like to be casual, so we can talk during it, which I think is nice for the audience to hear and an aspect I’m really looking forward to. I am a little bit older now. Who knows what I can do physically.

Moran: I like the term “quotes'' because I like the way Joan quotes and references texts in her performances, like the performance Reading Dante, 2008. Joan always arrives with a pretty strong gameplay about what’s going to happen. It always feels like you’re in a kind of cyclone, and then everything settles and then that’s the performance. Performing together often feels like friends talking to one another, checking each other along the way about how we got here.

CULTURED: What will rehearsals for this piece entail?

Jonas: I think we’ll rehearse a few times in MoMA’s theater space, because that’s where we’re going to be doing our performance.

Moran: One thing we do when we rehearse one of our duets is we play at 50 percent of the level we want to achieve. You have to save the rest for the actual performance, so you play just enough in a rehearsal to know, “Okay, this is going to be really great.” But you hold off until the audience is there. Something happens once an audience enters the room.

“Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning” will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from March 17 through July 6. Jonas and Moran’s new performance, A Lecture Demonstration, will debut at MoMA’s theater on March 26 at 7 p.m.

in your life?

in your life?