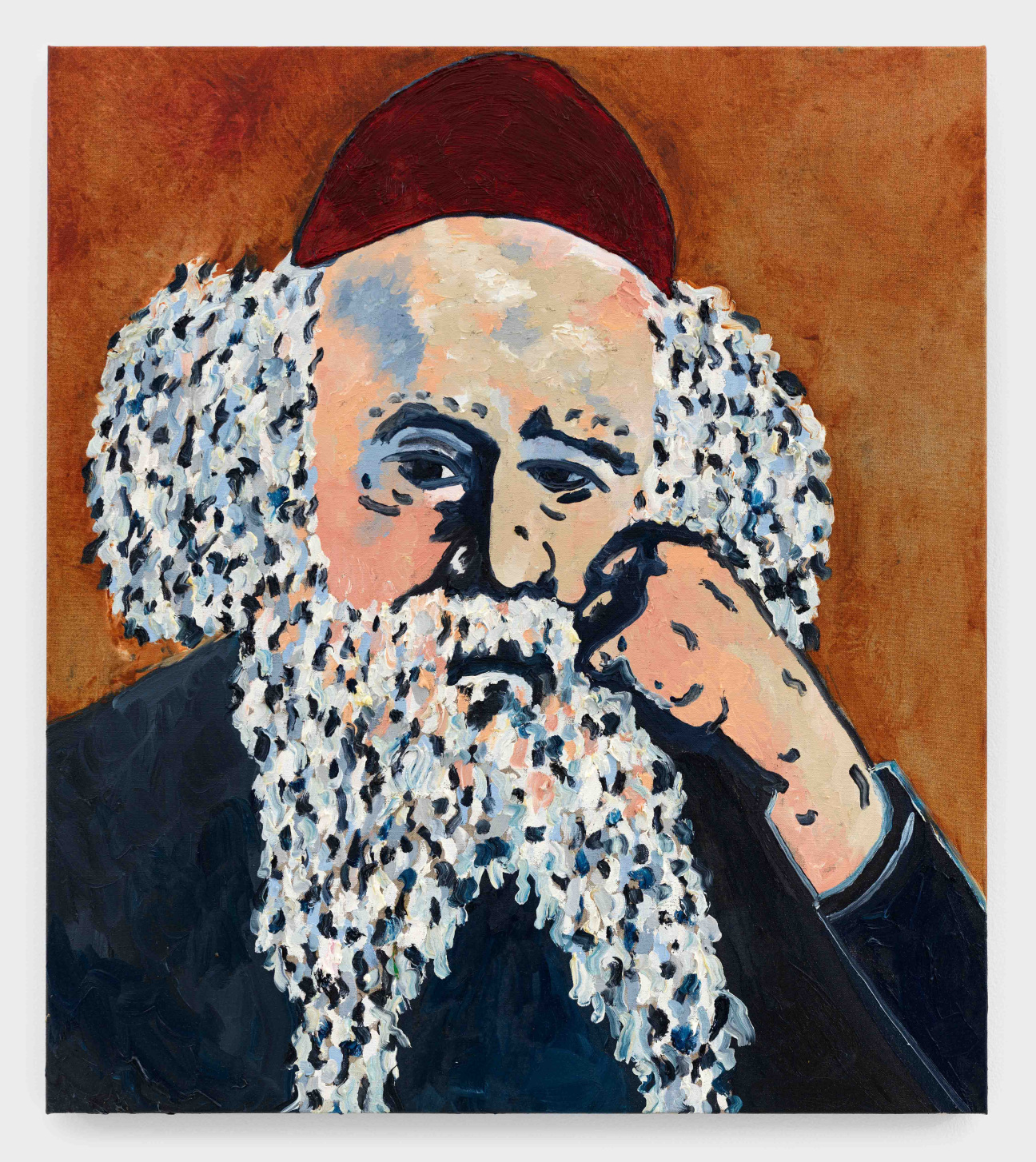

Joel Mesler never expected he would end up painting rabbis. The Los Angeles-born, East Hampton-based artist began the series after becoming the custodian of over 200 rabbi portraits that were being cast off by synagogues and younger Jewish people who had inherited them from their parents.

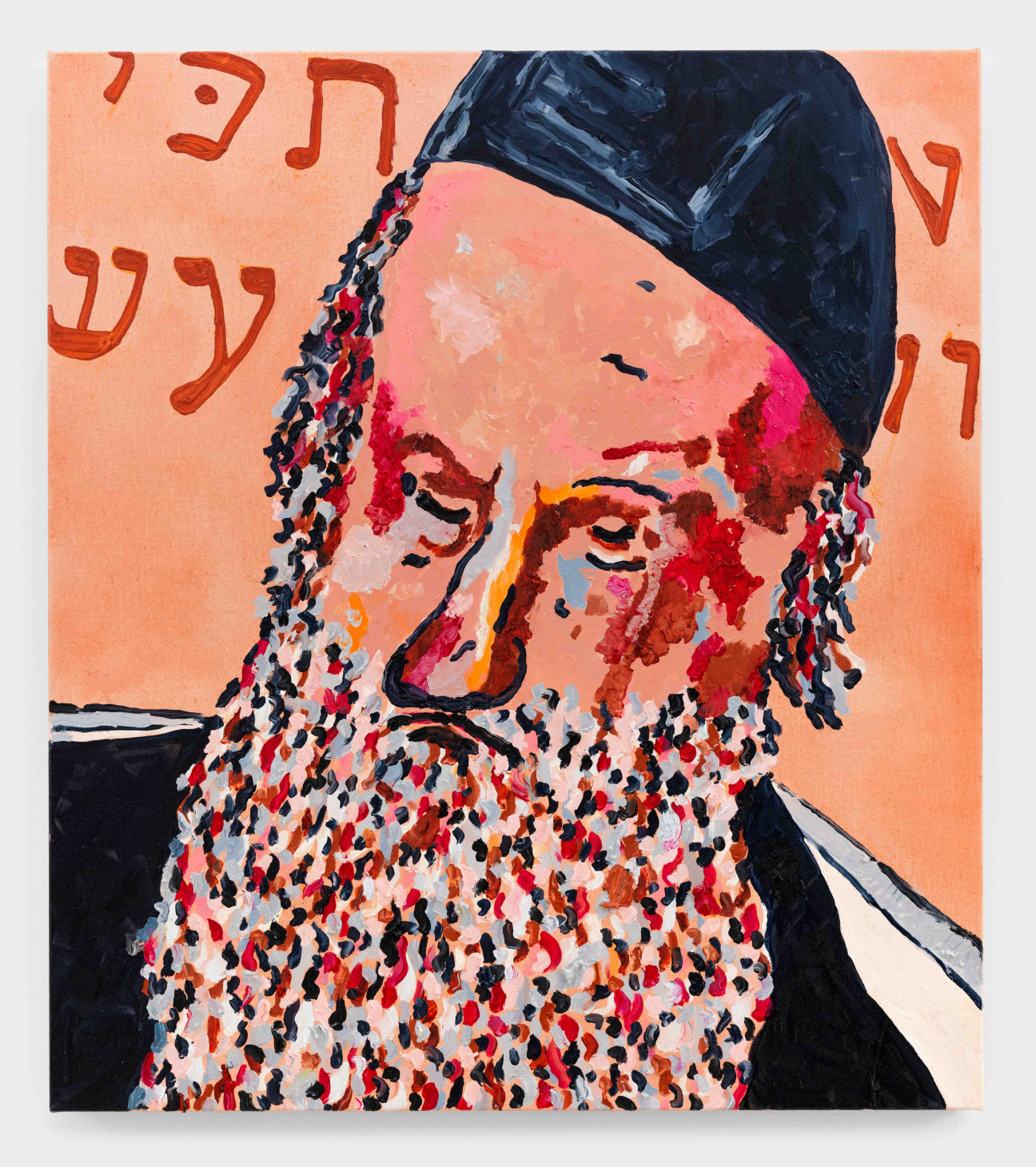

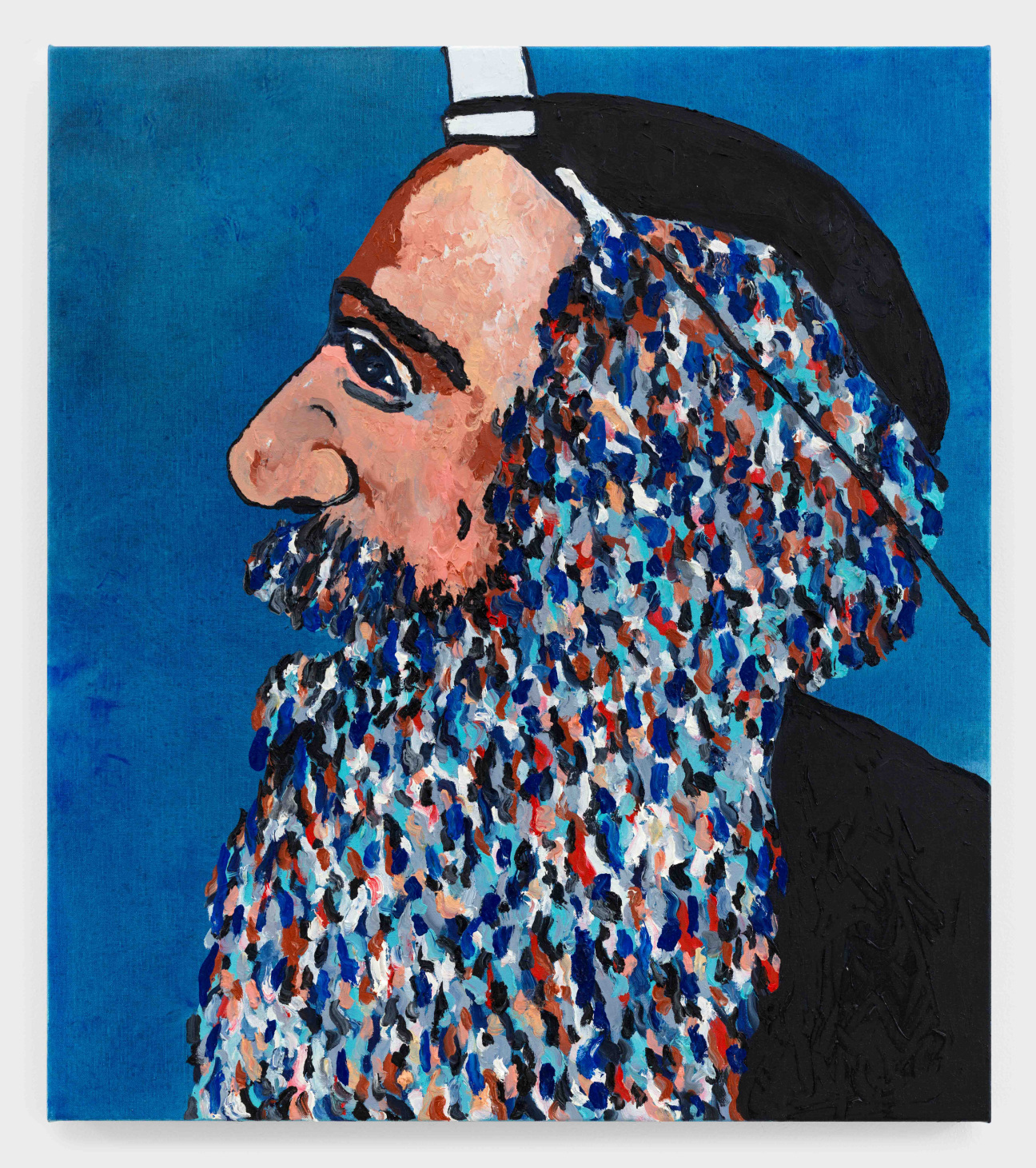

Moved to infuse them with new life, Mesler began copying the paintings, giving them a pop—almost disco—color treatment. He debuted the project at New York's Cheim & Read gallery in January, and since then he's only delved deeper into the subject. He will show the latest paintings, alongside a new artist book, at the ADAA Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory, which runs from Nov. 2 through 5. On Friday, Mesler will discuss the body of work with Chabad House Bowery's Rabbi Korn, and the Jewish Museum's Leon Levy associate curator Shira Backer. Ahead of the occasion, the beloved artist called up CULTURED to talk about the paradigm shift the rabbi paintings engendered in his career, and the arts community.

CULTURED: You've collected rabbi paintings for a while. How did you start?

Joel Mesler: When I was growing up, my parents had a couple rabbi paintings. I never really thought about it. When my mother passed away, my brother and I were going through her stuff. He was like, “I do not want anything to do with those fucking rabbis.” I asked my wife if I could hang them in the house, and she said, “I'd rather you not. I prefer these contemporary paintings we have.” So I put them around special places in the house and brought one to the studio. I've been collecting Ben Shahn books, paraphernalia, prints, and paintings for a while. As I was buying at all these weird Florida and upstate New York auctions, I realized all these rabbi paintings were coming up for sale and not only were they cheap, but there were times that nobody was even bidding. Without really thinking, I started acquiring these rabbi paintings.

Me being obsessive compulsive and an alcoholic—I'm in recovery, but I still have that disease—I can't do anything in moderation. Eventually, my wife said, “No more packages of rabbis can come to the house.” I had to get a storage unit. All of a sudden, I was at 200-plus rabbi paintings. At a certain moment I said to myself, I am a painter and even though I don't paint very well, I can give it my best shot to paint my rabbi collection. I didn't quite understand what I was doing. [The art dealer] John Cheim, who I have this really nice, nurturing friendship with, came by the studio—I don't think he really likes my other bodies of work very much, but he totally responded to these rabbis. I was like, “I don't know, it might throw a wrench in the other stuff I'm doing,” and he was like, “Let's just do it. We'll do it in my space and not through your other galleries. It’ll be different.”

We did the show, and people totally engaged with the work. In my parents' generation, you'd go over to friends’ houses and you'd see a rabbi on the wall, but my generation doesn't want rabbis on the walls. And all of a sudden I was like, "Wait a minute, now they want my rabbis." There was a weird paradigm shift. What was gonna be a personal, in-my-closet project became this larger endeavor. Now, it really feels like the core of what I'm doing.

CULTURED: If you have 200-plus rabbi paintings in your collection, is the goal to give all of them a new life? Or are you drawn to specific ones?

Mesler: Some paintings are easier for me to approach than others. I also try to pick rabbis that, in whatever weird way, I have an emotional connection to. I was saying to a rabbi friend of mine, “A lot of people say to me, ‘These rabbis, they seem sad and contemplative.’” There's a lot of melancholy or sorrow, and I always felt guilty about that. I would almost make excuses for them. I would say, "Maybe they're in prayer," or "Maybe they're studying," because there's usually a book, or "Maybe they're teaching the next generation," because there's usually a child. The rabbi said to me, "Maybe they were just sad. It's not so easy to be a rabbi. It's a lot of responsibility, especially back then."

CULTURED: You call yourself a custodian of lost rabbis. Can you talk about this role?

Mesler: It's almost like I fell in a ditch where I didn't know there was a missing piece of land, and now I have to spend all this time digging myself out of this ditch. I am now this weird rabbi painting conduit for synagogues. I feel this responsibility to take care of this bizarre niche of artworks. I was speaking to a Hillel earlier this year and said, “I'm getting older and I'm tired, and I do have other things to do. If there's somebody in this group that wants to continue this, I would gladly hand this over.”

CULTURED: Did anyone stand up?

Mesler: No, not fucking one. But I'm gonna keep saying it. When I do my talk at the ADAA, I'm gonna say it again.

CULTURED: How does this new series that you're showing with Cheim & Read at ADAA, “More Jews And Other Stories,” grow from the original series of rabbi paintings?

Mesler: These paintings are so much better than when I look back at the paintings in the Cheim & Read show. I see how naïve I was, literally in the mixing of paint, and how I defined certain features. I actually feel like these are successful paintings. In a perfect world, I'll look back at these in a year and be like, “Oh, those were naïve.”

CULTURED: You're going to be in conversation with Rabbi Korn of Chabad House Bowery on Nov. 3 as part of the ADAA talks program. How often do you two speak?

Mesler: I have a group of sober men that I speak to every day, I have my family, and then I have rabbis. This is what my life consists of now. Rabbi Korn shed so much light on my work. I did these books called “Jews and Other Stories.” I take pre-existing books and do a drawing of a Jew on one side and then a ghost print of that drawing on the other side. A ghost print is the technical name. What about the idea of the Jew as the ghost story? It is this beautiful idea that while any of us are alive, we can bring light and joy and goodness. But the unfortunate thing is when we're dead, we can no longer affect the world. And yet it's the same person. Maybe this speaks to the idea of generations or the story of the Jew. For him to bring things like that up to me, I thought, This is even deeper than deep.

CULTURED: You've made the new book project pointedly “wordless.” What made you decide to forego commentary?

Mesler: The irony is that I use text in my paintings. People are like, “Why do you use text in your work?” I'm totally dyslexic and super ADD. If there's a learning disability on the table, I've got it. So I think, How can I communicate as directly as possible? I guess I'll just put words on the canvas. There's such freedom in doing that. The books became this other manifestation or ephemera that came out of the paintings. I do everything in reverse—maybe that's the dyslexia—but the paintings have text and the books have pictures.

CULTURED: Your word paintings emphasize accessibilty. They have a really easy and light-hearted entry point. Do you think there's also something happening in terms of accessibility with these rabbi paintings? Like that you're providing Jewish people access to a cultural or religious lore they didn't even know wanted access to?

Mesler: That's so true. When I started making work again—you know, I was a failed artist the first time, and I was heavily into ego—this time around I was like, “Oh my God, I'm gonna make art now, where I could actually consider like the person looking.” I was concerned with accessibility and all these things that I thought were bad words before. Like, God forbid if somebody actually liked my art, I actually didn't like them. I was like, "You must be a loser if you like my art." As I got older and sober, I was like, "No, no, no, I actually want to care about other people and be in service to other people." If they're gonna give me money and then enjoy having it on the wall as opposed to just putting it in storage, that's a good thing.

I'm trying to stay away, very consciously, from talking about what's happening now. But as the darkness continues, it makes me want to bring the joy out and be like, "I don't wanna fight, I want to show the light." And I never thought about that in terms of the rabbi, but that's so interesting. Perhaps there is a parallel in looking at these old rabbi paintings that are a little melancholy and sad and thinking, What if I put some crimson red in there? I'm gonna make the rabbi a little more disco like, How do you like the rabbi now? Let's see what the Jew can do.

CULTURED: The art show benefits the Henry Street Settlement in the Lower East Side, which has been a significant area for the Jewish diaspora in New York for centuries. How does showing this work connect to the neighborhood that has meant so much for so many different communities, and particularly the Jewish community?

Mesler: That's where I got my footing [as a dealer] in New York. I landed on East Broadway. That is my shtetl. Life has a funny way of bringing you back—now, I'm here to serve. In Tzedakah [the Jewish term for charitable giving], if someone gives me $10, I'm giving away three of it. It's the 12 steps; it's like the clock.

in your life?

in your life?